15 Apr 2025

Mastitis in meat sheep: an overview

David Charles CertHE(Biol), BVSc, CertAVP(Sheep), PGCertVPS, MRCVS covers the causes, presentation and treatment options for this condition.

Figure 1. Ewe with pendulous udder.

Mastitis (inflammation of the mammary tissue) is a condition that any production-animal vet or farmer worldwide will be familiar with; however, much of the evidence and guidance available relates towards both clinical and subclinical mastitis in dairy cattle.

Far less is published concerning mastitis in sheep, and even less with regards to mastitis in meat sheep compared to dairy ewes.

While mastitis is an important condition affecting dairy sheep in the British Isles, this article will focus on infectious ovine mastitis in meat sheep within the UK and Ireland.

Causes

Worldwide, the significant majority of infectious mastitis in meat sheep is caused by Staphylococcus aureus and Mannheimia haemolytica.

One UK study reported S aureus as the causative agent in 68% of cases (Hariharan et al, 2004); similarly, a Norwegian study confirmed S aureus infection in 65.3% of cases (Mørk et al, 2007), while Mavrogianni et al (2007) reported that the two organisms together cause 80% of all cases of ovine infectious mastitis.

A first peak is reported in the first week postpartum, and some studies have demonstrated a second peak, on average, four weeks postpartum (Cooper et al, 2016).

Other bacterial species have also been cultured from affected ewes, including Escherichia coli, Arcanobacterium pyogenes and Clostridium perfringens (Winter and Clarkson, 2012; Gelasakis et al, 2015).

Additionally, mastitis in meat sheep can also be associated with maedi-visna (covered in more detail by the author in a previous issue; Charles, 2024), Leptospira hardjo, coagulase-negative staphylococci, and Mycoplasma agalactiae (albeit, M agalactiae is not currently present in northern Europe).

S aureus and M haemolytica are both commensal organisms, tending towards opportunistic infection after damage to the teat tissue or teat end.

S aureus is naturally found on the skin of most ruminants. M haemolytica can often be found as a natural commensal of the upper respiratory tract of lambs, infecting the ewe’s mammary tissue when over sucking or trauma to the teat occurs. Scott and Jones (1998) demonstrated that only a low dose was required to establish infection via this route.

How common is ovine mastitis?

Understanding the true extent and, therefore, impact of clinical mastitis on sheep farms in the UK is a difficult task, with many cases going undiagnosed – or at very least unreported. With the majority of cases occurring during the intensive lambing time, it is easy to understand why challenges in recording and reporting occur.

Estimating the true incidence rate of clinical mastitis entirely depends on a farmer’s ability to record and detect clinical cases, which will be variable based upon frequency of checks and attentiveness of farm staff.

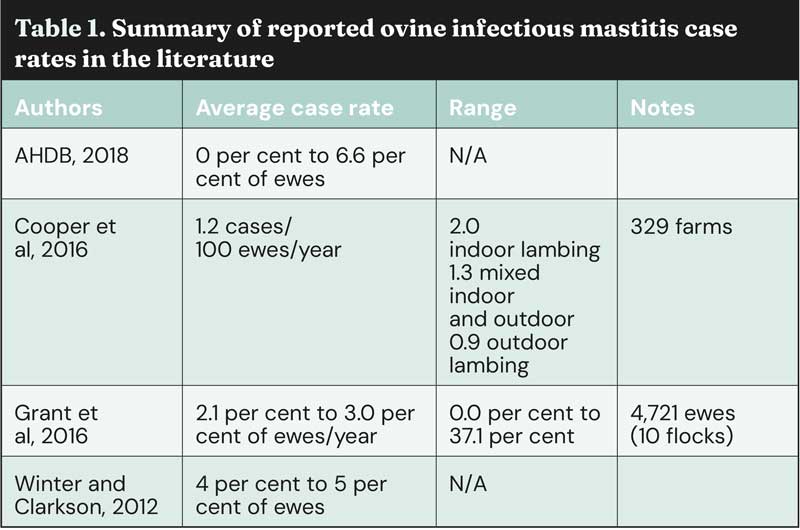

Various authors have undertaken research designed to better understand the incidence of ovine infectious mastitis on UK sheep farms, with varying results (Table 1) of anything from 0% up to 37.1% of ewes per year being reported as having acute mastitis.

Subclinical mastitis remains an important disease affecting the UK sheep industry, reducing lamb growth rates (particularly in the first eight weeks of life; Huntley and Green, 2012), lamb survival and driving other economic losses through production delays, such as reducing the time available for ewes to regain condition between weaning and mating.

Risk factors

Various risk factors for acute and chronic mastitis have been described, with acute mastitis being the biggest risk factor for the development of intramammary masses (IMM; odds ratio [OR] 12.39) and chronic mastitis.

Grant et al (2016) found that risk factors for acute mastitis included: underfeeding protein in pregnancy (OR 4.05); downward-pointing teats (OR 4.68); forward-pointing teats (OR 2.54); litter size of 2 or more lambs (OR 2.65) and non-traumatic teat lesions (OR 2.09). Cooper et al (2016) also found that indoor lambing and frequency of pen bedding changes were influential on the incidence rate of clinical mastitis.

To this extent, the AHDB promoted a scoring system for teat position in non-dairy ewes (AHDB, 2018), advocating for a score 3 for teat position (placement of teats on udder on a horizontal plane), score 5 for teat angle (placement of teats on udder on a vertical plane), and score 7 for udder drop (distance from ventral abdominal wall when viewed from behind). For reference, the ewe in Figure 1 would be a score 1 or 2 for udder drop (1 = nearest floor, 9 = nearest ventral abdominal wall).

A 3, 5, 7 score ensures: sufficient distance between the two teats laterally, allowing twin lambs to suckle at the same time; sufficient clearance from the floor to reduce contamination; and teats on a 45° angle to the udder, allowing for easy-reach suckling. The score 5 (45° angle) has been demonstrated to be positively associated with greater lamb weight gain (AHDB, 2018).

Furthermore, research on meat sheep indicates that downward-pointing teat angles and forward-facing teat positions are linked to a higher risk of acute mastitis. This increased risk may be attributed to the fact that teats in these positions are less shielded by the non-woolly skin in the flank, making them more vulnerable to environmental factors and exposure to pathogens such as E coli. Additionally, these teat positions are known to hinder lambs from suckling effectively.

Orf virus damages the epithelial cells of the udder, allowing bacterial ingress and the development of mastitis, while ovine pregnancy toxaemia has been proven to reduce the immune system and predispose ewes to M haemolytica mastitis (Barbagianni et al, 2015).

Approach to acute ovine mastitis

Clinical presentation

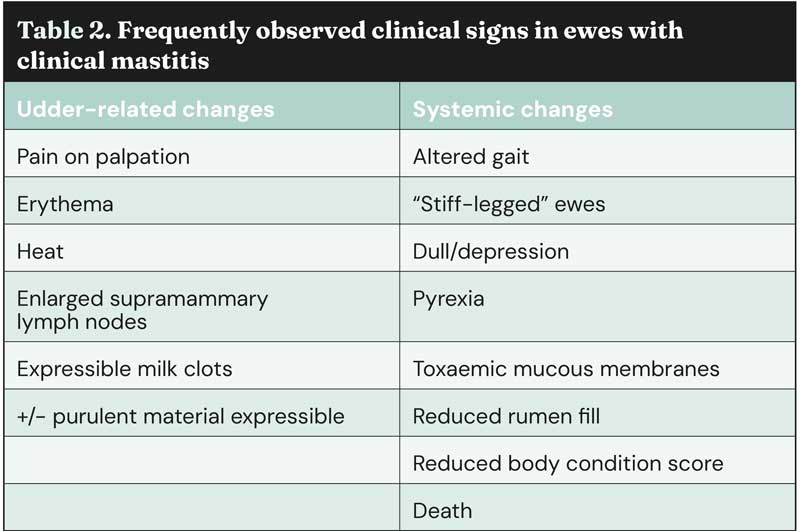

Ewes affected with ovine mastitis can present in a number of ways, depending on the severity of disease and the speed of detection. Table 2 details the frequently observed clinical signs in acute ovine mastitis split by udder-related and systemic clinical signs.

In the worst cases, gangrenous mastitis and signs of endotoxaemic shock are observed; in these cases, discolouration of the mammary tissue is observed (arising to the colloquial name of “blue bag” or “black bag”), with these areas being friable, necrotic, malodorous and cold to the touch. In the worst cases, sloughing of the udder is observed.

Sometimes, farmers will detect mastitis after identifying “hollow” or hypothermic lambs as a result of starvation, resulting from a reduced tolerance to suckling by the ewe or from a lack of palatable milk.

Diagnosis

In the author’s experience, diagnosis is regularly based solely upon clinical signs and/or response to treatment – often driven by economic factors.

However, in flocks with high incidence rates, further investigations are definitely warranted. Further investigations can include use of the California Mastitis Test (which can also be used for screening mid-lactation; McLaren et al, 2018), culture and sensitivity of purulent material, or gangrenous lesions of the udder. In less severe cases, culture and sensitivity of the milk can be performed.

Samples must be collected aseptically, wearing gloves, and should be collected into sterile containers without preservative. At the time of writing this article, single samples cost between £20-25 per sample, with the cost reducing if multiple samples (more than five) are submitted simultaneously (Axiom Veterinary Laboratories, 2024; Biobest Laboratories, 2025).

Treatment

Firstly, it is important to note that animals with acute gangrenous mastitis and systemic illness should be culled on welfare grounds.

For all other cases of clinical mastitis, the following should form part of a treatment protocol:

- Antibiotics.

- NSAIDs.

- Fluid therapy.

Antibiotics are indicated in clinical cases, with penicillin, amoxicillin and oxytetracycline being appropriate first-line products (they are all category D “care” antibiotics; European Medicines Agency, 2020). Tilmicosin is licensed for mastitis in sheep and is efficacious as a second-line treatment (as a category C “prudence” antibiotic) – albeit selecting to prescribe it is complicated slightly by the limitations on farmers administering it.

In the author’s experience, a six-day course of amoxicillin is often efficacious, and long-acting preparations are available, reducing the number of injections required.

All of the tilmicosin products on the market are long acting, and make efficacious second-line alternatives. Enrofloxacin is also licensed, but as an HP-CIA in category B “restrict” and should only be used as a last resort if resistance to all the other antibiotics listed has been demonstrated.

No evidence exists for the use of topical oxytetracycline sprays in these cases, and farmers should be dissuaded from using such products.

It remains the case that no NSAIDs are licensed for use in sheep in the UK. Noting the off-licence withdrawal periods, it is appropriate to recommend meloxicam subcutaneously. The recommended dose for this is 1mg/kg, as per the licensed dose for sheep in the southern hemisphere (Boehringer Ingelheim, 2020). Readers more familiar with cattle medicine should note that this is twice the dose for cattle licensed in the UK.

Fluid therapy is often underutilised in the treatment of small ruminants. However, it is important to remember that mastitis is a dehydrating condition that also presents with animals in an electrolyte deficit. Correcting the electrolyte deficit, as well as the hypovolaemia, is vital to restoring normal hydration status. This can be provided orally with an isotonic electrolyte solution, or – where indicated – intravenous fluid therapy.

Animals presenting in endotoxaemic shock require intravenous fluid therapy, although in some farms the economics of such intensive treatment must be considered and discussed with the farmer, and weighed against the prognosis for survival and ability to rear lambs to the point of weaning.

Ongoing advice

Incidence rates of clinical mastitis increase in indoor lambing systems with time; flocks recording high incidence rates near the start of the lambing season should add stringent checks to their post-lambing protocols, with a focus on checking udders in the first week of life. Additionally, a number of checks should be carried out, where practical, through until at least week four of lactation. Attention must also be given to the lambs of any ewes affected by acute mastitis.

Milk quality and tolerance for suckling will be reduced, negatively impacting milk intake and lamb growth rates. In their study involving 1,570 lambs, Griffiths et al (2019) found that growth rates of lambs from ewes with clinical mastitis at docking and weaning were lower than those from ewes without clinical mastitis by 19.6g per day and 28.9g per day, respectively.

As evidenced by Grant et al (2016), acute mastitis is a significant risk factor for the development of IMM and chronic mastitis. IMM and acute mastitis also significantly increase the risk of “blind teats” at lambing, which are non-productive teats such that lambs must be fostered or dealt with as “orphan lambs”, increasing the time and economic impact.

All ewes should have their udders checked prior to mating, but particular attention should be paid to the udders of ewes that had acute mastitis in the previous lactation to check for the development of IMM (Figure 2) or any conformational teat changes. Ewes with IMM or unfavourable teat conformation pre-mating should not be bred from where possible, and culled from the flock.

Broadly speaking, it appears that farmers in the UK follow such advice closely, with 94.2% reporting that they cull all ewes affected by clinical mastitis, and 92.4% reporting that they do not breed again from ewes with clinical mastitis in the previous lactation.

However, improvements could be made in checking for IMM or conformational abnormalities, both pre-mating and pre-lambing. Half (50%) of farmers reported that they did not check udders specifically for mastitis, and the average frequency of checking udders decreased the further into lactation: approximately 20% did not check udders at all in the first week of lactation, rising to more than 33% in weeks two to four (Cooper et al, 2016). This may be why the “second peak” at approximately four weeks into lactation is not as well recorded in the UK as it is in other countries, such as Norway.

Subclinical cases

As with many conditions affecting production animals, for every clinical case many more subclinical cases will exist. These may not present as systemically unwell or with apparent udder changes; nonetheless, the elevated somatic cell counts and reduced milk quality will contribute to reduced daily liveweight gains in lambs and – in the worst cases – increased lamb mortality.

Lamb mortality investigations should include a level of somatic cell count testing and, where relevant, culture with or without sensitivity of milk samples.

Economic impact

It is hard to estimate the true economic impact of ovine infectious mastitis, and further work and modelling is required to do so.

However, as a condition it negatively impacts ewe health and welfare, lamb growth rates, colostrum quality, lamb mortality, medicines spend, culling rates and farmer time – so the economic impact will be significant to any farm business affected.

Prevention

Advising farmers to have a robust culling policy based on the known risk factors (udder conformation, teat lesions or history of acute mastitis) and presence of IMM is an important part of prevention.

Much has been learned regarding the importance of nutrition and adequate body condition score in the prevention of acute mastitis – especially with regards to adequate provision of protein in the late gestation period. A detailed discussion of gestational nutritional requirements of sheep is beyond the scope of this article, but is covered well in other content, including “Feeding the ewe” (Povey et al, 2024).

A vaccine for immunisation of ewes to reduce the incidence of subclinical cases of S aureus mastitis was licensed for use in sheep in the UK in 2018; it is licensed for use in animals older than eight months, and the data sheet reports onset of immunity as six weeks. Two doses are required at five and three weeks before the expected parturition date every year (NOAH, 2025). The price per dose will vary depending on location, but the author was able to find it via an online pharmacy retailing between £4.64-4.98 per dose (excluding VAT; would require a prescription fee), which for some farmers may be a barrier to uptake.

The author has limited experience with flocks using the vaccine, but is aware of articles citing reduction in incidence rates in flocks with a 10% or higher prevalence of S aureus mastitis (HIPRA, 2024).

Conclusions

Ovine mastitis remains a disease of significant economic and welfare concern to the UK sheep industry.

Practitioners should be aware of appropriate treatment protocols and be able to advise their clients of appropriate management procedures, to reduce the risk of occurrence within their flocks.

- Appeared in Vet Times (2025), Volume 55, Issue 15, Pages 14-18

References

- AHDB (2018). Understanding mastitis in sheep, tinyurl.com/2s3zv5t7

- Axiom Veterinary Laboratories (2024). Axiom Farm Price List 2025.

- Barbagianni MS et al (2015). Pregnancy toxaemia as predisposing factor for development of mastitis in sheep during the immediately post-partum period, Small Ruminant Res 130: 246-251.

- Biobest Laboratories (2025) 2025 Price List, tinyurl.com/4snzd25v

- Boehringer Ingelheim (2020). Metacam 20mg/ml datasheet solution for injection Australia, tinyurl.com/yc7ezhz3

- Charles D (2024). Sheep health – focus on UK’s ovine iceberg disease threats, Vet Times Livestock 10(2): 12-16.

- Cooper S et al (2016). A cross-sectional study of 329 farms in England to identify risk factors for ovine clinical mastitis, Prev Vet Med 125: 89-98.

- European Medicines Agency (2020) Categorisation of antibiotics for use in animals, tinyurl.com/5x47s5xp

- Gelasakis AI et al (2015). Mastitis in sheep – the last 10 years and the future of research, Vet Microbiol 181(1-2): 136-146.

- Grant C et al (2016). A longitudinal study of factors associated with acute and chronic mastitis and their impact on lamb growth rate in 10 suckler sheep flocks in Great Britain, Prev Vet Med 127: 27-36.

- Griffiths KJ et al (2019). Associations between lamb growth to weaning and dam udder and teat scores, N Z Vet J 67(4): 172-179.

- Hariharan H (2004). Bacteriology and somatic cell counts in milk samples from ewes on a Scottish farm, Can J Vet Res 68(3): 188-192.

- HIPRA (2024). Trade stand, Sheep Veterinary Society Autumn Conference 2024, Morpeth.

- Huntley S and Green L (2012). Mastitis in ewes: towards development of a prevention and treatment plan – final Report, University of Warwick, tinyurl.com/s2wu29cn

- Mavrogianni VS et al (2007). Bacterial flora and risk of infection of the ovine teat duct and mammary gland throughout lactation, Prev Vet Med 79(2-4): 163-173.

- McLaren A et al (2018). New mastitis phenotypes suitable for genomic selection in meat sheep and their genetic relationships with udder conformation and lamb live weights, Animal 12(12): 2,470-2,479.

- Mørk T et al (2007). Clinical mastitis in ewes; bacteriology, epidemiology and clinical features, Acta Vet Scand 49(1): 23.

- NOAH (2025) VIMCO emulsion for injection for ewes and female goats, NOAH Compendium Online, tinyurl.com/3w4u6uvn

- Povey G et al (2024). Feeding the ewe, tinyurl.com/3m3wjs3p

- Scott MJ and Jones JE (1998). The carriage of Pasteurella haemolytica in sheep and its transfer between ewes and lambs in relation to mastitis, J Comp Pathol 118(4): 359-363.

- Winter AC and Clarkson MJ (2012). A Handbook for the Sheep Clinician (7th edn), CABI, Wallingford.