26 Mar 2024

Ovine infectious abortion – how to deal with outbreaks

Abortions of lambs can take an emotional, as well as a financial, toll on farming clients. Here, the author focuses on common causes, diagnosis and the valuable advice farm vets can provide ahead of the main lambing period.

Infectious abortion is of great welfare and economic concern to the sheep industry in the UK. Losses can come on quickly and suddenly within a flock, sometimes offering farmers (and vets) little time to intervene.

The “industry accepted” target is fewer than 2% abortions per year (Agriculture and Horticulture Development Board [AHDB], 2016; Farm Advisory Service, 2020) and abortion accounts for 30% of lamb losses, which can contribute to the financial and emotional impact of an outbreak (Crilly et al, 2021). It is important vets undertaking any amount of sheep work understand the signs and risks of ovine infectious abortion. This article will focus on the most common causes, providing practical advice and information ahead of the main lambing season.

Many of the causative agents are zoonotic in nature, posing an additional risk to both farm and veterinary staff. With many veterinary practices offering to see lambings and caesarean sections at their practice (rather than on farm), clear procedures, protocols and an understanding of the zoonotic nature of these cases is important to protect all staff. This includes those who are not doing clinical work, but may be pregnant, or at risk of zoonotic disease.

One part of this is the use of sufficient PPE, with one study (across 21 practices) finding 87% of vets used protective gloves for a lambing, but only 25% did for a caesarean section (Charles and Stockton, 2022).

The five most frequently diagnosed causes of infectious ovine abortion by the APHA (2022; Table 1) remain:

- Chlamydia abortus

- Toxoplasma gondii

- Campylobacter species

- Listeria species

- Salmonella species

| Table 1. Data from the Veterinary Investigation Diagnosis Analysis report (APHA, 2022) | |

|---|---|

| Infectious agent | Frequency (%) |

| Chlamydia abortus | 30 |

| Toxoplasma gondii | 28 |

| Campylobacter species | 23 |

| Listeria species | 6 |

| Salmonella species | 4 |

| Other | 9 |

In 2022, only 46% of cases submitted to the APHA for postmortem examination, or sample analysis, produced a definitive diagnosis. Other notable pathogens, outside of the top five, included Schmallenburg virus, border disease and Coxiella burnetii.

In the UK, vaccines are only commercially available against two of the top five pathogens (C abortus and T gondii). The T gondii vaccine is only available as a live attenuated form and must be administered at least three weeks before mating (NOAH, 2023a). Three vaccines against C abortus are commercially available in the UK; two are live attenuated and must be administered at least four weeks before mating (NOAH, 2023b; 2023c). The third is an inactivated vaccine and this can be used in the face of an outbreak (NOAH, 2023d). A Campylobacter species vaccine can be imported using a special import certificate (Jones and Charles, 2023).

Vaccination of ewes is not without its problems; studies have demonstrated variable compliance by farmers. Hall et al (2022) reported almost half of all respondents kept vaccines for more than 48 hours after broaching and variable success at identifying the correct site for vaccination. However, more than 80% showed an appetite for practical training courses to improve knowledge and technique.

Vaccines against T gondii and C abortus are viewed, by the sector, as important enough to secure a “category one vaccine” designation in the NOAH Livestock Vaccination Guidelines (Lovatt, 2022). What this means for the farm vet is discussed in detail in other articles previously published in Vet Times (Charles, 2023). In summary, NOAH’s stance is that category one vaccines should be given as a default unless a flock-specific discussion has taken place between the client and their vet to justify not using them (which should be reviewed regularly).

Nationally, it is estimated that 50% of breeding ewes are vaccinated against C abortus and 31% against T gondii (AHDB, 2023).

It is important that vets doing sheep work in the lambing season are familiar with the common causes, how to diagnose them and how to advise their clients in the face of a suspected abortion outbreak.

Panels 1 and 2 lay out important questions to ask clients and advice to provide to farmers, while Table 2 discusses the samples required for detection of different pathogens at postmortem examination.

- Is this the first abortion? Frequency of two per cent of the flock, or three abortions in two days, should definitely be investigated

- When was the ewe expected to lamb?

- Is the ewe vaccinated against Chlamydia abortus and Toxoplasma gondii?

- Were any ewes bought in this year?

- Have all lambs been aborted, or are there others in utero?

- Any changes in management/diet, or recent stress?

- Does the farmer have the aborted material and fetus?

- Can the farmer text a photo of the lamb and fetus? This allows you to formulate initial thoughts, before advising for the postmortem examination or farm visit.

- Isolate aborted ewes, for a period of three to four weeks, or until vaginal discharge has dried up.

- Wear gloves and PPE when handling aborted ewes, placenta and aborted fetus.

- Consider placing aborted fetus and placenta into a secure bag (for example, clean feed sack with zip tie) for postmortem examination.

- Disinfect pens and destroy (incinerate) bedding that has been in contact with aborted material and vaginal discharge.

- Securely dispose of any PPE used and wash all clothing on removal.

- Advise the zoonotic potential of the likely pathogens – especially stress the risk to any pregnant females (this includes those not working with the sheep, but at risk of handling clothing).

- Discuss any diagnostic testing that is recommended, or samples you may wish to take.

- Advise any relevant treatment for the ewe, plus or minus confirm time of visit for examination.

- Advise not to foster any lambs on to the aborted ewe.

| Table 1. Samples required for diagnosis of ovine abortion, by causative agent | |

|---|---|

| Pathogen | Tissues required |

| Chlamydia abortus | Placenta (with at least one cotyledon and membrane and intercotyledonary tissue) Maternal blood |

| Toxoplasma gondii | Placenta (with at least one cotyledon and membrane) Fetal membrane Fetal brain Maternal blood |

| Campylobacter species | Placenta Fetal stomach content Lung +/or liver |

| Salmonella species | Fetal stomach content Vaginal swab (ewe) |

| Listeria species | Placenta Fetus |

| Border disease | Spleen Kidney Thyroid Maternal blood |

| Schmallenberg virus | Umbilical tissue Fetal fluid Maternal blood |

Note, it is never wrong to submit the entire lamb and placenta to the APHA for postmortem examination (Figure 1) – this will maximise the chances of achieving a diagnosis. Submitting blood samples (plain and lithium-heparin tubes) from the ewe has some merit as well.

Chlamydophila abortus

C abortus, also known as enzootic abortion of ewes, is endemic in the UK and occurs globally, with the exception of Australia and New Zealand. It is zoonotic and can cause pregnant women to abort.

The economic impact of this disease is vast. Latest estimates are that it costs the UK sheep industry £20 million per year. With an estimated cost of £85 per abortion, the flock of 100 ewes that suffers an outbreak (which may see as much of 30% of the flock abort) could face losses of at least £2,550 (Mearns, 2007; Ceva Animal Health, 2022).

C abortus tends to cause abortion in the final two to three weeks of gestation. The most common way it is introduced to the flock is via the introduction of externally sourced replacements.

Infected aborted material can present with a fairly pathognomic appearance, with placentitis and diffuse grey thickening of the intercotyledonary spaces. This is not always detected; therefore, diagnostic testing (including postmortem examination) is usually required for a definitive diagnosis. Red/brown vaginal discharge and staining of the tail and perineum are also frequently observed.

In the face of an outbreak, the inactivated vaccine can be used. However, it is a multi-dose protocol, and benefit can still be had from treating ewes that abort with oxytetracyclines to reduce the shedding of bacteria. Naive ewes are infected through contact with aborted material or vaginal discharge.

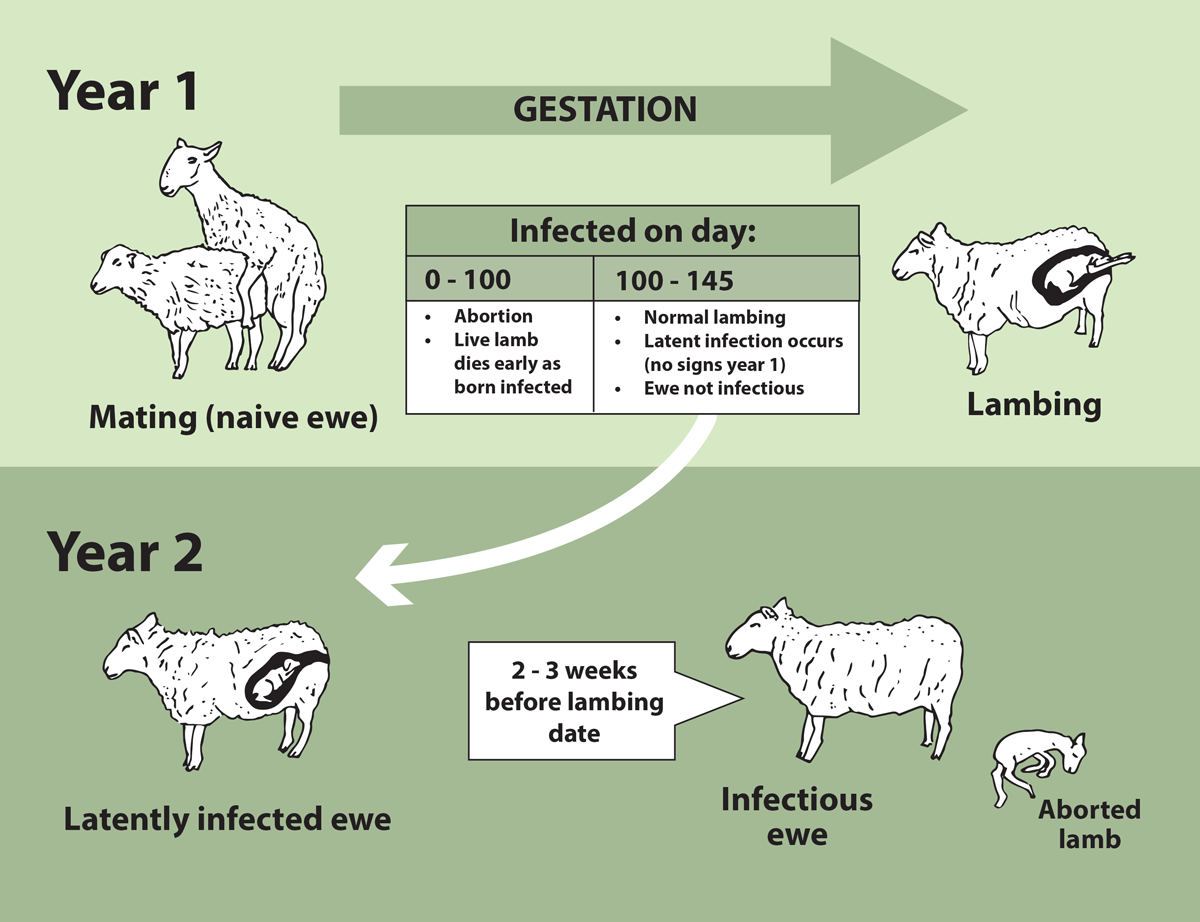

Ewes infected in the 2024 lambing season will develop latent infection and will abort until the following year (Figure 2) – which can cause “abortion storms” the year after a small number of abortions are diagnosed. Abortion storms can easily cause 30% of the flock to abort. Vaccinating a latently infected ewe will have limited effect, and infected animals can shed bacteria for up to two years after abortion.

Subsidised diagnostic testing of aborted, or barren, ewes for C abortus or T gondii exposure is often available to vets in the spring and summer (such as FlockCheck from MSD Animal Health or AssureEwe from Ceva Animal Health; Over, 2022).

T gondii

T gondii is a protozoal parasite. The definitive host is the cat, with mammals (including sheep and humans) acting as the intermediate host. Infection occurs when cat faeces, containing the protozoal oocysts, are ingested.

It is common for infection to occur when cat faeces are deposited in, or around, the concentrate feeder space/feed face. Otherwise, it can be when cats contaminate hay (for bedding) or have access to non-secured feed bins. One gram of cat faeces can contain enough oocysts to infect thousands of ewes (Dabritz et al, 2007).

Oocysts are hardy and can survive in the environment for a long time. Sheep to sheep infection does not occur, so mixing sheep prior to mating will not have any benefit. However, ewes that recover from infection often develop immunity.

Reproductive outcomes vary depending on time of infection. If ewes are infected in the first 60 days, the fetus is resorbed, and farmers will record a barren ewe at scanning. Infection occurring between days 60 and 120 of gestation present with late-gestation abortion, often with mummified fetuses, stillbirths or weak lambs that die.

Placental changes are evident, with focal white spots on the cotyledons (colloquially known as white strawberry appearance; Dubey, 2009). Control focuses on vaccination, rodent control (infected rodents develop neurological signs and are more easily caught by cats) and the securing of feed stores.

The prevalence of T gondii may well be increasing. MSD reported its FlockCheck scheme found T gondii in at least one ewe (the scheme allows six ewes that were barren or aborted to be tested) on 66.4% of the 375 UK sheep farms tested (MSD Animal Health, 2021).

Campylobacter species

Abortions due to infections by Campylobacter species are most frequently caused by C fetus subspecies fetus and C jejuni.

Spread is through faecal-oral infection, contact with infected material and oral secretions. Outbreaks often follow the introduction of carrier sheep to a naive flock. Diagnosis may be achieved on gross postmortem examination, with lesions on the fetal liver and placentitis observed; otherwise, PCR testing is required. Treatment has predominantly involved the administration of tetracyclines. However, reports suggest tetracycline-resistant strains are developing in other parts of the world (Sahin et al, 2008).

Listeria species

Abortions due to listeriosis are usually due to Listeria monocytogenes or L ivanovii, and typically occur in late gestation. Horizontal transmission is possible. However, the majority of cases occur due to spoiled silage or soil ingestion.

Clinical signs include abortion, pyrexia, anorexia, depression and, occasionally, septicaemia – which may be fatal. At postmortem examination, necrosis of the placenta (cotyledon and intercotyledonary spaces) is observed, and autolysis of the fetus is common. The “traditional” neurological signs of listeriosis may also be observed. Treatment of affected ewes should include penicillin, fluid therapy (IV or oral) and supportive care.

Studies have reported L monocytogenes occurring in conjunction with T gondii (De Angelis et al, 2022) and further work is needed to understand if multifactorial abortion occurs more frequently than expected.

Coxiella burnetii (Q-fever)

Coxiella burnetii is an obligate intracellular bacterial pathogen. In the past few years, farm vets’ awareness of this disease has increased, with an increase in testing and vaccination in the dairy sector. Infected aborted material, urine and/or faeces contaminate the environment, facilitating the spread of the disease. It is zoonotic, infecting humans via the same routes by which ewes are infected. C burnetii can also present as infertility (an increased number of barren ewes at scanning), or an increase in cases of mastitis and metritis after lambing.

The UK does not currently have a licensed vaccine for use in sheep. An inactivated vaccine is available for use in cattle and goats, which may be able to be used under the prescribing cascade. However, it is the opinion of the author that veterinary surgeons should consult the marketing authorisation holder before doing so.

Non-infectious abortions

Not all abortions in the lambing season are due to infectious agents. Non-infectious abortion remains an important cause of losses. Ovine pregnancy toxaemia, stress, hypocalcaemia, mycotoxins and dog-worrying can all cause non-infectious abortion in sheep, to name but a few.

Unfortunately, dog attacks and dog-worrying are growing in prevalence, with 70% of respondents to a study by the National Sheep Association (2023) experiencing an attack in the past 12 months.

Bluetongue virus

Bluetongue virus (BTV) has been demonstrated to cause abortions and other reproductive disorders.

Given the widespread outbreak of BTV-3 in the Netherlands at the end of 2023, the circulating BTV-8 in France and Belgium, and the detection of BTV in the south and east of England at the end of 2023, vets should keep BTV on their differential diagnosis list during lambing 2023-4.

Clinical signs include abortion, fetal mummification, stillbirth and congenital malformation if live lambs are delivered (Osburn, 1994; APHA, 2018; Rizzo et al, 2021).

BTV is a notifiable disease, and vets should act accordingly if it is suspected.

Conclusion

Owing to the economic and welfare importance of ovine abortion, all vets seeing any breeding sheep should have a good understanding of the common causes and how to diagnose them. Most of these diagnoses take some time, so issuing relevant advice to farmers in the meantime will be crucial.

Vaccination against the two most frequently diagnosed causes is an important part of any control/prevention plan, as vaccination is often not possible in the face of an outbreak.

As we continue to ensure responsible use of antibiotics, it is not enough for farmers to rely on blanket oxytetracycline use if abortions occur.

Special importance must be given to the zoonotic risk of any sheep abortion (until all zoonotic agents are ruled out), and appropriate PPE should be used and guidance to clients should be issued. As the demand for “lambing courses” and “pre-lambing talks” increases, it is important to use these opportunities to communicate the risks and processes for managing an abortion to clients ahead of lambing.

References

- AHDB (2016). Lamb: cost of production benchmarks, https://ahdb.org.uk/lamb-cost-of-production-benchmarks

- AHDB (2023). Use of vaccines in sheep, bit.ly/49MPoMt

- APHA (2018). Bluetongue virus serotype 8 – malformed calves and abortions, http://apha.defra.gov.uk/documents/ov/Briefing-Note-1819.pdf

- APHA (2022). VIDA Annual Report 2022, https://public.tableau.com/app/profile/siu.apha/viz/VIDAAnnualReport2022/VIDAAnnualReport2022

- Ceva Animal Health (2022). Can you afford not to vaccinate against enzootic abortion? https://enzooticabortion.co.uk/protecting-your-farm

- Charles D (2023). NOAH vaccination guidelines – what do they mean for sheep vets?, Vet Times 53(9): 11-12.

- Charles D and Stockton D (2022). Ovine Caesarean sections and assisted vaginal deliveries: a clinical audit, Livestock 27(6): 282-287.

- Crilly J et al (2021). Sheep abortion – a roundtable discussion, Livestock 26(Suppl 5): S1-S15.

- Dabritz HA et al (2007). Detection of Toxoplasma gondii-like oocysts in cat feces and estimates of the environmental oocyst burden, Journal of the American Veterinary Medical Association 231(11): 1,676-1,684.

- De Angelis ME et al (2022). Co-infection of L monocytogenes and Toxoplasma gondii in a sheep flock causing abortion and lamb deaths, Microorganisms 10(8): 1,647.

- Dubey JP (2009). Toxoplasmosis in sheep – the last 20 years, Veterinary Parasitology 163(1-2): 1-14.

- Farm Advisory Service (2020). An Introduction to benchmarking for sheep, www.fas.scot/downloads/an-introduction-to-benchmarking-sheep

- Hall LE et al (2022). Surveying UK sheep farmers’ vaccination techniques and the impact of vaccination training, Veterinary Record 191(4): e1798.

- Jones C and Charles D (2023). Causes of ovine abortion, vaccination protocols and uptake: an overview, Livestock 28(4): 172-179.

- Lovatt F (2022). NOAH Livestock Vaccination, Guideline for dairy, beef, and sheep sectors: section 4 - sheep, bit.ly/3wQqmxL

- Mearns R (2007). Abortion in sheep 1. Investigation and principal causes, In Practice 29(1): 40-46.

- MSD Animal Health (2021). Toxoplasmosis warning, Veterinary Record 189(7): 269.

- National Sheep Association (2023). NSA Sheep worrying by dogs survey 2023: main results, bit.ly/49JdPdQ

- NOAH (2023a). Toxovax datasheets, NOAH Compendium Online, www.noahcompendium.co.uk/?id=-476558

- NOAH (2023b). Cevac Chlamydia datasheet, NOAH Compendium Online, www.noahcompendium.co.uk/?id=-473027

- NOAH (2023c). Enzovax datasheets, NOAH Compendium Online, www.noahcompendium.co.uk/?id=-454659

- NOAH (2023d). Inmeva Suspension For Injection Datasheet, NOAH Compendium, www.noahcompendium.co.uk/?id=-474449

- Osburn BI (1994). The impact of bluetongue virus on reproduction, Comparative Immunology, Microbiology and Infectious Diseases 17(3-4): 189-196.

- Over P (2022). Subsidised testing scheme available to ID early lamb loss causes, Farmer’s Guide, February, bit.ly/49F5Oql

- Rizzo H et al (2021). Is bluetongue virus a risk factor for reproductive failure in tropical hair sheep in Brazil?, Acta Scientiae Veterinariae 49(2021): doi.org/10.22456/1679-9216.112591

- Sahin O et al (2008). Emergence of a tetracycline-resistant Campylobacter jejuni clone associated with outbreaks of ovine abortion in the United States, Journal of Clinical Microbiology 46(5): 1,663-1,671.