13 Jan 2026

Periparturient ‘downer ewes’ – metabolic disorders of sheep

David Charles CertHE(Biol), BVSc, CertAVP(Sheep), PGCertVPS, MRCVS looks at this issue in the ruminant species and management of the condition

Image: majeczka/ Adobe Stock

Recumbent ewes in the periparturient period remain an all too common problem, and in many cases these recumbent animals can be indicative of wider problems within the flock.

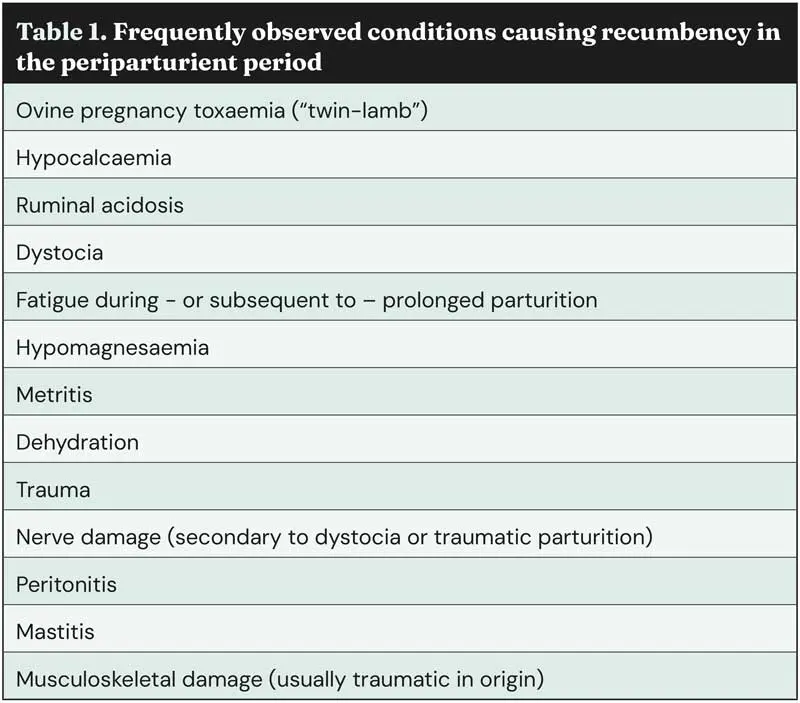

Table 1 shows a list of the most frequently observed differential diagnoses for recumbent ewes in the periparturient period.

While non-metabolic causes of recumbency – including obstetrical difficulties and mastitis, as covered in other articles by the author (Charles, 2025a; Charles and Stockton, 2022) – do present in the periparturient period, this article will focus on metabolic disorders, their aetiology, diagnosis, treatment, and flock-level impact.

Metabolic disorders

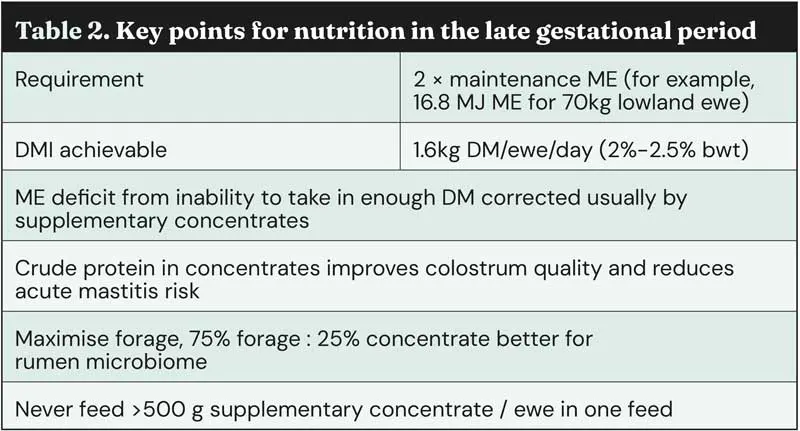

Metabolic disorders are all about nutrition – a topic vets often shy away from – however, an understanding of the energy and nutritional requirements of late-gestation and early-lactation ewes is vital to help vets advise appropriately around metabolic disorder risk status, prevention, and treatment. The disorders often arise from an imbalance between the nutritional demands of the ewe and developing lambs, and the nutritional input.

As such, it is useful to re-visit some basics of ovine nutritional requirements in the late gestational period (Table 2).

This article will focus on four metabolic disorders that can affect ewes in the periparturient period:

- ovine pregnancy toxaemia (OPT)

- ruminal acidosis

- hypocalcaemia

- hypomagnesaemia

OPT

With OPT – often referred to by its colloquial name of “twin-lamb disease” – it is important that clinicians do not allow the colloquial name to blind their judgement for both prevention and treatment of this condition.

OPT can affect ewes of all ages and carrying any number of lambs in utero.

Cause

Sheep differ from dairy cattle, in that negative energy balance and associated hypoglycaemia typically arise in late gestation, when more than 70% of fetal growth occurs. Maternal glucose is the primary fetal energy source; while early gestation demands are modest, late‑term requirements rise to approximately 30g to 40g of glucose per fetus per day (Iqbal et al, 2022).

As fetuses enlarge, rumen capacity decreases, reducing dry‑matter intake and daily metabolisable energy supply. This imbalance is most pronounced in ewes carrying multiples, but can also affect single‑bearing ewes if nutrition is inadequate.

Insufficient glucose triggers mobilisation of adipose triacylglycerols into free fatty acids (FFAs) and glycerol. FFAs are converted to acetyl‑CoA, and when oxaloacetate is limiting, excess acetyl‑CoA is diverted to ketone production. Resultant hyperketonaemia suppresses hepatic gluconeogenesis, culminating in OPT. Accumulation of ketone bodies also induces metabolic acidosis, promotes osmotic diuresis with sodium and potassium loss, and may progress to uraemia in advanced cases.

Diagnosis

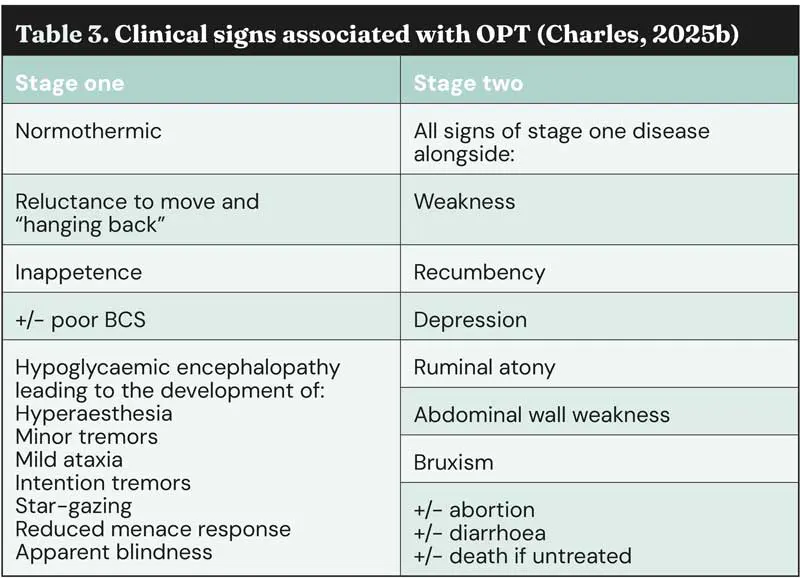

Clinical signs associated with OPT are shown in Table 3; these can be grouped into two stages, with progression from stage 1 to stage 2 often occurring over several days.

Diagnosis is often made based upon clinical signs alone as a presumptive diagnosis; however, the increase in access to pen-side diagnostic testing allows for accurate and appropriate diagnostic testing to be carried out; β-HB can be tested pen-side, with values between 1.0mmol/L to 2.9mmol/L indicating subclinical disease and values greater than 3.0 mmol/L indicating clinical disease (Crilly et al, 2021) – often associated with advanced clinical signs. A thorough history with attention to ration formulation, feed access, water provision and scan results can aid diagnosis.

Treatment

Treatment of OPT revolves around three key principles: rapidly correcting the hypoglycaemia, correcting dehydration and electrolyte deficits, and – if appropriate – removing the energy drain.

Rapidly correcting hypoglycaemia

This is essential in OPT to prevent irreversible neurological damage. In ewes already showing neurological signs, intravenous glucose is appropriate, while in less severe cases oral glucose precursors can support hepatic gluconeogenesis. However, prolonged administration beyond six days risks toxicity, and euthanasia may need to be considered if treatment approaches this duration (Brozos et al, 2011).

Propylene glycol is widely used and inexpensive, entering the tricarboxylic acid cycle via pyruvate to generate glucose. However, it does not provide the most rapid correction of hypoglycaemia and hyperketonaemia.

Glycerol offers a faster response: glycerol-water mixtures elevate serum glucose within one hour, compared with at least nine hours for propylene glycol (Alon et al, 2020).

In subclinical OPT, a combination of 70g glycerol and 20g propylene glycol per dose was more effective than intravenous glucose with insulin or cracked corn in correcting metabolic disturbances (Cal-Pereyra et al, 2015). Clinicians should remember that glucose powders will be ineffective, as rumen microbes ferment them before absorption.

A high‑energy palatable feed, such as soaked fodder beet, may support recovery by stimulating intake, but affected ewes may refuse it and it cannot supply energy rapidly enough, so should not be used as the only way of providing energy.

Correcting dehydration and electrolyte deficits

Rehydration is a critical, but often overlooked, component of treating OPT. Although farmers frequently prioritise glucose precursors, ewes commonly present with significant dehydration. This is exacerbated when propylene glycol is used alone, as it does not contribute water.

Glycerol, which must be diluted to penetrate the rumen mat (Hippen et al, 2008), provides some fluid, but additional rehydration is usually required. Dehydration arises from ketone‑induced osmotic diuresis (Sargison, 2007) and cortisol‑mediated suppression of antidiuretic hormone, further increasing urine output.

Electrolyte correction is equally important. Potassium and sodium deficits are substantial, with potassium losses reaching 1.5mmol/L, or more than or equal to 30% of serum concentration in clinical cases. Subclinical ewes are also affected, and survivors have been shown to have smaller electrolyte deficits than non‑survivors (Iqbal et al, 2022). Concurrent hypocalcaemia occurs in approximately 25% of OPT cases and promotes disease progression in hyperketonaemic ewes. Lower calcium levels are associated with poorer outcomes (Iqbal et al, 2022), supporting the inclusion of oral calcium in treatment protocols – either alone or preferably in a combination product that provides sufficient glycerol, calcium, and potassium. Methods of calcium provision are explored further in the “Hypocalcaemia” section of this article.

Removing energy drain

In severe cases of OPT, removing the lambs can improve the ewe’s prognosis, although caesarean success declines if performed more than five days before term.

Dexamethasone induction is effective after day 135 – ideally after day 138 – with Zoller et al (2015) recommending 16mg twice daily, though 16mg once daily has also produced lambing within 42 to 54 hours (Charles, 2025b).

A note on NSAID provision

NSAIDs are useful in managing OPT, as 73% of affected ewes show pain (Crilly et al, 2021) and inflammation contributes to hyperketonaemia. No NSAIDs are licensed for sheep in the UK, so use under the cascade and appropriate withdrawal periods are required. Meloxicam should be dosed at the higher dose of 1mg/kg in sheep.

Flock-health considerations

The impact of OPT extends far beyond ewe and lamb mortality. Flocks with clinical cases may have subclinical hyperketonaemia in up to 40% of animals, contributing to increased abortions, higher lamb mortality, poor‑quality colostrum, and reduced lamb birthweights and daily liveweight gain. Clinical OPT is associated with high rates of dystocia (50%), metritis (25%) and increased mastitis risk (Barbagianni et al, 2015), alongside reduced milk yield, retained fetal membranes and altered gestation duration.

Untreated cases show ewe mortality of 70% to 90%, with fewer than 15% of lambs expected to survive.

Ruminal acidosis

Cause

When excess concentrates are taken into the rumen, large carbohydrates are released. As a result, an increase in volatile fatty acids (VFA) is released into the rumen; these weak acids reduce ruminal pH, as concentrates require less chewing than forage, releasing less salivary buffer and providing less ruminal scratch factor – which in turn means that the ruminal absorptive capacity is reduced. The reduction in ruminal pH allows lactate-producing species to proliferate, which in turn means additional l-lactate is produced, rapidly lowering the ruminal pH further (l-lactate is up to 10 times more potent an acid than VFAs). Water starts to be drawn into the rumen from the ECF along the new, reversed, osmotic gradient.

At this low pH, Lactobacillus species produces the potent neurotoxin, D-lactate and further damage occurs to the ruminal epithelia: allowing for bacteria (such as Escherichia coli, which thrives in an acidic environment) and acid to “leak” into the bloodstream.

Excess lactate, which cannot be absorbed by the rumen, spreads into the large intestine, leading to osmotic diarrhoea and driving dehydration further.

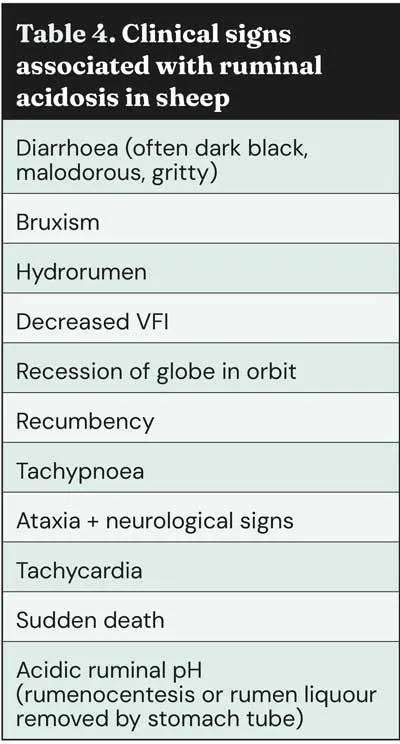

The entry of acid into the bloodstream rapidly causes a metabolic acidosis, leading to end-stage clinical signs (Table 4) and, if untreated, neurological decline, coma and death.

Diagnosis

Clinical signs are shown in Table 4; however, this is often a diagnosis reached during postmortem examination – pH testing of ruminal content can be performed (often below pH 5.5 – acute cases can see pH <4.0) and a characteristic malodour is often present.

Additionally, damage in the form of micro-abscesses of the rumen wall, and signs consistent with ruminitis, can be observed (Figure 1).

Treatment

If acute ruminal acidosis is detected, rapid interventions are required to preserve life. Rapid neutralisation of ruminal pH is required, and several “antacid” products on the market contain buffers or alkalinising agents to achieve this. One study demonstrated the potency of MgO as an antacid, neutralising ruminal pH within 30 minutes – faster than MgOH or NaHCO3, which are other popular choices. Correction of dehydration and prevention of further production of lactic acid are essential. Often, commercial “antacid” products are delivered by drenching the ewe and are dissolved in water to concurrently correct dehydration. Providing activated charcoal will bind VFA and prevent further production of lactate. The recommended dose for sheep is 1.6g/kg of activated charcoal orally.

Yeast (Saccharomycese cerevisiae or brewer’s yeast) will support the rumen flora, yielding an increase in cellulolytic bacterial species which compete with the lactate-producing species for glucose, allowing lactate-utilising species (Megasphaera elsdenii) to increase in number, reducing the concentration of lactate in the rumen and supporting an increase in ruminal pH.

Clients should be advised to provide long-chop roughage or hay for several days, and limit or remove access to concentrates. The provision of B vitamins may be beneficial if neurological signs are present. Nutritional advice and assessment of other ewes should be carried out, as other ewes may be at risk.

Flock-health considerations

Ruminal acidosis in the periparturient period is often secondary to feed-related issues – this includes, but is not limited to, over-supplementation with concentrations, ewes breaking into feed bins, ration formulation errors, and providing concentrates once a day in bulk rather than limiting to levels of less than 500g/ewe/day. Therefore, one case of acute ruminal acidosis can be an indicator of many more to follow or become at risk due to being in a state of subacute ruminal acidosis.

Care should be taken to gradually introduce or “step” concentrates over several days when introduced to the pre-lambing ration, and it is important to provide adequate roughage and trough space (75% forage : 25% concentrates target), and water provision and access should be checked. Ewes require 4.5 litres per ewe per day in late gestation, with 5cm to 10cm per ewe if troughs are provided or one drinking space per 20 ewes.

Hypocalcaemia

In contrast with hypocalcaemia in dairy cattle, hypocalcaemia in ewes is typically observed prior to parturition – in the late gestational period. It typically arises in the final six weeks of gestation, with only very occasional cases of parturient paresis reported; it most commonly affects older ewes in their third pregnancy or beyond.

Cause

Hypocalcaemia in the periparturient period is driven by the temporary drop in blood calcium concentration that occurs when fetal bone mineralisation (three to four weeks before lambing) demands increase faster than ewes can mobilise calcium from the bone pool (a process that takes on average 24 to 36 hours).

Nutrition plays an important role, as hypocalcaemia in ewes often results from dietary imbalance – particularly if rations fail to provide enough calcium to meet both fetal and maternal maintenance needs. Dietary cation anion balance strategies have not been shown to prevent the condition in sheep (Macrae, 2020).

High phosphorus intake further increases risk by inhibiting renal activation of vitamin D3. On a practical level, farmers should avoid fodder beet tops and ryegrass in late gestation, as their high oxalate content binds calcium and reduces availability.

Vitamin D deficiency may also contribute, given its essential role in calcium absorption; inadequate vitamin D limits intestinal uptake to 10% to 15% of dietary calcium in humans, with similar findings in ruminants (Hodnik et al, 2020).

Vets also should not overlook stress-induced hypocalcaemia. Unfortunately, it remains all too common in the UK. This leads to the redistribution of calcium and magnesium in the body, risking a reduction in serum calcium concentration. These events can also lead to hyperventilation and respiratory alkalosis, which drives an increase in calcium binding to protein in the blood, reducing further ionised calcium concentration in blood.

Diagnosis

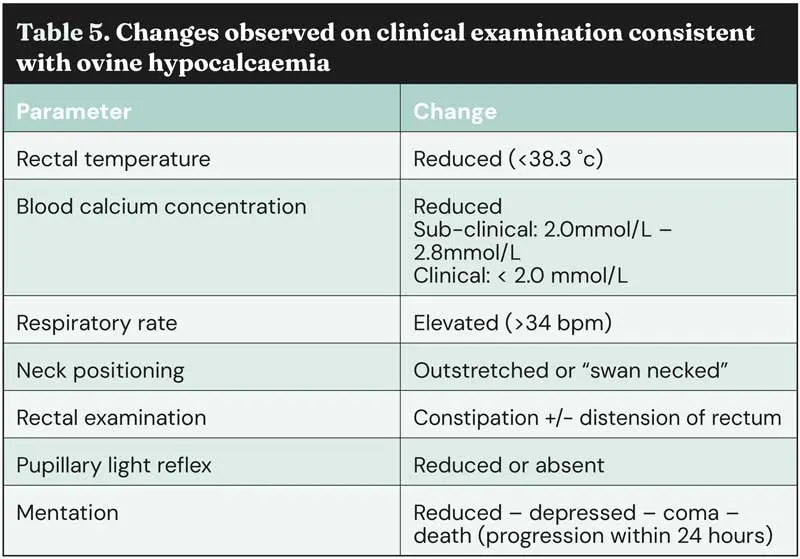

Diagnosis is often reached after clinical examination and a detailed history. Clinical signs are detailed in Table 5.

Several clinical signs are shared with OPT; however, important differences – which can be life-saving – include:

- Reduced pupillary light reflex.

- Functional blindness.

- Altered neck position.

- Hypothermia.

- A faster progression to recumbency, depression and death.

Treatment

Slow intravenous administration of 20ml to 40ml of a solution containing 40% calcium borogluconate and 5% magnesium hypophosphite hexahydrate produces a rapid rise in serum calcium.

Traditionally, this was followed by (or often replaced with) subcutaneous 20% calcium borogluconate to counter the short duration of IV calcium and the frequent rebound hypocalcaemia with associated recumbency.

However, since the licensed sheep formulation was withdrawn, it has become evident that subcutaneous calcium is poorly absorbed and can cause local irritation. When using the subcutaneous route, effective correction of calcium levels requires dividing the dose into small volumes administered at multiple sites.

Many vets and farmers will find it easier and cheaper to provide oral calcium. This is a more reliable way of providing long-lasting calcium to the ewe than subcutaneous administration. Care should be given to the calcium salt selected, with calcium chloride providing a short-lived effect when given orally compared with longer-lasting options, such as calcium propionate (Goff and Horst, 1993). Many ewes will be ambulatory, defecating and urinating within five minutes of treatment (Winter and Grove-White, 2025).

Ewes with hypocalcaemia have been shown to have concurrent dehydration and benefit from rehydration and provision of sodium and potassium – this should form part of the ongoing supportive care of affected animals after calcium deficiency is corrected.

Flock-health considerations

Hypocalcaemia is estimated to affect 0.4% to 2% of the UK ewe population annually (Macrae, 2020). Although less common than OPT, it is equally important for vets and farmers to recognise, as misdiagnosis is frequent, and cases are often mistaken for OPT or respiratory disease, which can lead to unnecessary use of antibiotics.

Affected ewes may die within 24 hours, making rapid and accurate diagnosis critical. Improving farmer awareness is essential – particularly as it is estimated that fewer than 5% of hypocalcaemic ewes are reported to a veterinarian.

Hypomagnesaemia

Cause

Hypomagnesaemia (“grass staggers”) most commonly occurs after turnout and during the first six weeks of lactation, when high milk yield creates a substantial magnesium demand.

Sheep’s milk contains higher levels of calcium, magnesium and phosphorus than cow’s milk, and ewes depend entirely on ruminal absorption to meet magnesium requirements for both maintenance and lactation.

When ewes graze rapidly growing spring pasture or grass fertilised with nitrogen or potassium, magnesium intake may be inadequate, either because these minerals can inhibit ruminal magnesium uptake or because the forage itself contains insufficient magnesium due to fast growth.

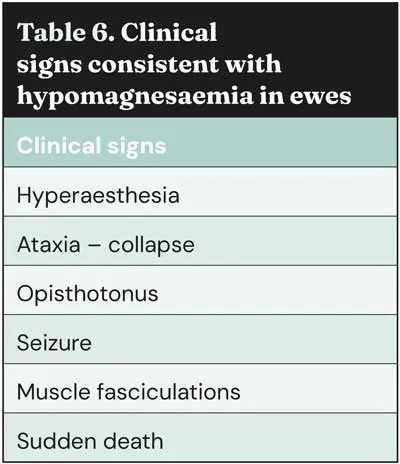

Diagnosis

Often, ewes are found dead or as “sudden death” cases, and signs from the environment such as evidence of paddling or seizure in the grass/ground (Figure 2) can be suggestive of seizure or opisthotonus before death. If ewes are found alive then clinical signs (Table 6) can aid diagnosis, alongside blood test (magnesium concentration less than 0.6mmol/L).

If found dead, postmortem aqueous humour magnesium concentration can aid diagnosis (less than 0.33mmol/L within 24 hours of death allows diagnosis).

Treatment and flock-health considerations

If the ewe is alive, administer 20ml/70kg of warm calcium borogluconate with magnesium intravenously, alongside 50ml/70kg of 25% magnesium solution subcutaneously.

Many affected ewes are found dead; therefore, a single confirmed case should prompt flock‑level prevention.

Magnesium can be supplemented via drinking water, concentrates, or intra‑ruminal boluses, though boluses provide only three to four weeks of cover, while lactating ewes at pasture require approximately 7g magnesium per day (AHDB, 2024).

Conclusion

Metabolic disorders in sheep remain a major cause of preventable loss, yet early recognition, accurate diagnosis and targeted nutritional management can dramatically improve outcomes.

Strengthening farmer awareness and veterinary guidance is essential to reducing morbidity, safeguarding ewe welfare and improving flock productivity across all production systems.

The use of pre-lambing visits, nutritional assessment and pre-lambing blood testing can be valuable tools to aid discussions with clients and optimise nutrition to prevent the occurrence of metabolic disorders in the periparturient period.

- Use of some of the drugs in this article is under the veterinary medicine cascade.

- This article appeared in Vet Times (2026), Volume 56, Issue 2, Pages 10-13.

David Charles is an experienced livestock vet and RCVS-recognised advanced practitioner in sheep health and production – one of just eight vets to hold such status. He now splits his time between NoBACZ Healthcare (as their international business development manager) and independent veterinary consultancy (with clients including farms, animal health companies, and educational institutions). He is a trustee of RCVS Knowledge, a ROSA advisor, on the committee for the Sheep Veterinary Society and the editorial board of UK-Vet Livestock journal. He was a member of the inaugural LVS30Under30, and he was named the BVA Young Vet of the Year (2024).

References

- AHDB (2024). Feeding the ewe, tinyurl.com/4ckcztfv

- Alon T, Rosov A, Lifshitz L, Dvir H, Gootwine E and Moallem U (2020). The distinctive short-term response of late-pregnant prolific ewes to propylene glycol or glycerol drenching, J Dairy Sci 103(11): 10,245-10,257.

- Barbagianni MS, Spanos SA, Ioannidi KS, Vasileiou NGC, Katsafadou AI, Valasi I, Gouletsou PG and Fthenakis GC (2015). Increased incidence of peri-parturient problems in ewes with pregnancy toxaemia, Small Rumin Res 132: 111-114.

- Brozos C, Mavrogianni VS and Fthenakis GC (2011). Treatment and control of peri-parturient metabolic diseases: pregnancy toxemia, hypocalcemia, hypomagnesemia, Vet Clin North Am Food Anim Pract 27(1): 105-113.

- Cal-Pereyra L, González-Montaña JR, Benech A, Acosta-Dibarrat J, Martín MJ, Perini S, Abreu MC, Da Silva S and Rodríguez P (2015). Evaluation of three therapeutic alternatives for the early treatment of ovine pregnancy toxaemia, Ir Vet J 68: 25.

- Charles D (2025a). Mastitis in meat sheep, Vet Times, tinyurl.com/2ry3rvxk

- Charles D (2025b). Major metabolic disorders of sheep: what is new and what can we do?, Livestock 30(Suppl 2a): S29-S35.

- Charles D and Stockton D (2022). Ovine caesarean sections and assisted vaginal deliveries: a clinical audit, Livestock 27(6): 282-287.

- Crilly J, Phythian C and Evans M (2021). Advances in managing pregnancy toxaemia in sheep, In Pract 43(2): 79-94.

- Goff JP and Horst RL (1993). Oral administration of calcium salts for treatment of hypocalcemia in cattle, J Dairy Sci 76(1): 101-108.

- Hippen A, DeFrain J, Linke P (2008). Glycerol and other energy sources for metabolism and production of transition dairy cows, Proc 19th Annu Florida Rumin Nutr Symp, Gainesville: 1-6.

- Hodnik JJ, Ježek J and Starič J (2020). A review of vitamin D and its importance to the health of dairy cattle, J Dairy Res 87(S1): 84-87.

- Iqbal R, Beigh SA, Mir AQ, Shaheen M, Hussain SA, Nisar M and Dar AA (2022). Evaluation of metabolic and oxidative profile in ovine pregnancy toxemia and to determine their association with diagnosis and prognosis of disease, Trop Anim Health Prod 54(6): 338.

- Macrae A (2020). The recumbent ewe, Livestock 25(3): 136-140.

- Sargison N (2007). Pregnancy toxaemia. In Aitken ID (ed), Diseases of Sheep (4th edn), Blackwell Publishing, Hoboken.

- Winter A and Grove-White D (2025). A Handbook for the Sheep Clinician (8th edn), CAB International, Wallingford.

- Zoller DK, Vassiliadis PM, Voigt K, Sauter-Louis C and Zerbe H (2015). Two treatment protocols for induction of preterm parturition in ewes – Evaluation of the effects on lung maturation and lamb survival, Small Rumin Res 124: 112-119.