12 Sept 2016

Primary decision-making in diagnosing equine colic

Sarah Freeman, Karen Rickards, Adelle Bowden, John Burford and Gary England look at the role of patient history and physical examination when horses present with this abdominal pain symptom in the first of a two-part article.

Figure 2. Postmortem image of maxillary dental arcade in a donkey, showing multiple pathologies, including absence of 208, multiple diastema (106/107, 108/109, 110/111, 206/207, 209/210, 210/211) and gross periodontal pocketing with impaction of food material.

Colic is the term used to describe clinical signs of abdominal pain. Colic, therefore, describes a symptom, rather than a specific disease.

Diagnosing what has caused a horse to show signs of colic is often challenging as many different possible causes exist, including non-gastrointestinal causes of abdominal pain.

The most common types of colic (idiopathic, spasmodic or tympanic) describe conditions where a definitive diagnosis and underlying cause are frequently not identified1,2. These are usually mild medical cases that respond to analgesics and/or spasmolytic treatment.

It is, instead, important to differentiate critical conditions, such as infectious or surgical conditions where rapid intervention may have a significant impact on the outcome3.

Diagnostic approach should, therefore, be aimed at identifying the type of disease – particularly those requiring early intervention or different treatment options. A variety of diagnostic tests can be used to investigate abdominal pain in horses, ranging from faecal sand tests to exploratory laparotomy.

Key factors that influence choice of diagnostic tests are the cost of testing, availability of equipment, and the risk to the horse and the vet or owner/handler4.

This first part of a two-part article focuses on the primary assessment and decision making when a horse first presents with colic.

It reviews the role of patient history and physical examination in decision making, including key differences in the assessment of donkeys compared to horses. Part two will review the most commonly used diagnostic tests for colic.

Patient history

The first and fundamental steps in decision making for diagnostic approach are the history and physical examination findings (including assessment of pain and demeanour). In many cases, this will provide a strong indication of the type of colic and further tests required.

The information collected on the primary assessment of a horse with colic can vary4, but potential risk factors should be included in the clinical history. A wide range of possible risk factors for colic have been investigated.

These include:

- stereotypies5

- aspects of management (including type and frequency of feed, exercise, access to pasture, watering and stabling)6

- parasite management strategies7

- previous clinical history8

- seasonal factors9

- dental problems8

Some factors have been associated with specific causes of colic, such as increasing age of the horse with small intestinal strangulation10, oral stereotypies with epiploic foramen entrapment11 and aspects of pasture management with grass sickness12,13.

Varying levels of evidence exist for different possible risk factors and it may not be feasible to take a detailed history in some emergency circumstances. The strongest evidence is for age and breed of the horse, change in feed/management and previous history of abdominal pain14, and these should be considered essential aspects of history taking.

Physical examination

Physical examination findings are a key component of determining the required diagnostic tests, and identifying and triaging critical cases. Aspects that can identify critical cases include severe and continuous pain, marked cardiovascular changes and absence of gastrointestinal sounds in one or more quadrants1.

Other components of the patient history and physical examination can be important “triggers” for considering other disease types and different diagnostic approaches. Examples would be pyrexia as an indicator for infectious diseases, leading to diagnostic tests, such as haematology, faecal culture and/or abdominocentesis, and a history of weight loss, leading to diagnostic tests for conditions such as cyathostomosis, inflammatory bowel disease and neoplasia.

Critical conditions can cause rapid physical changes and deterioration in a relatively short period of time (Figure 1) and, therefore, repeated assessments and re-evaluation of any provisional diagnoses or conclusions (including the need for further tests) are essential.

Critical cases must be identified as early as possible – in a study of horses presenting to primary practitioners with colic, 84% of critical cases (164 out of 195) were euthanised or died1.

Many reasons exist as to why owners may decide against surgical treatment, but these cases also require rapid identification and decision for euthanasia to minimise pain and suffering.

Selection of diagnostic tests

History, physical examination, rectal examination and nasogastric intubation constitute the fundamental tests used in the diagnosis of colic. Abdominal palpation per rectum and nasogastric intubation are the most commonly used tests and will be discussed in the second article in this series.

Further diagnostic tests will be selected based on the outcomes of these and are broadly focused on three main categories: identifying surgical/critical cases and their prognosis, identifying infectious causes of colic (including parasitic causes) and investigating recurrent/chronic cases of colic.

Table 1 provides a summary of the indications and limitations for abdominocentesis and abdominal ultrasonography.

| Table 1. Indications and limitations for use of abdominocentesis and abdominal ultrasonography in horses presenting with clinical signs of abdominal pain | ||

|---|---|---|

| Diagnostic test (assessments) | Indications | Limitations/complications |

| Peritoneal fluid analysis (physical properties, total protein, lactate concentration, cytology and cell count) | Further information required to differentiate medical versus surgical conditions. Further information required to determine prognosis for survival. | Abnormal findings reflect non-specific changes within the abdominal cavity. For example, current commercial lactate tests do not differentiate between tissue damage from surgical lesions versus enterocolitis17. |

| Suspected peritonitis, including clinical signs of depression, anorexia, pyrexia and abnormal posture; haematology changes with no underlying cause identified; abnormal fluid on abdominal ultrasound). | Potential risks/complications include risk of injury to vet, infection at sample site and iatrogenic damage to other organs18. | |

| Abdominal masses, suspected neoplasia or abscesses based on rectal examination, ultrasonography or other finding. | Abnormal cells may not be shed into, or detected in, peritoneal fluid samples. | |

| Abdominal ultrasonography | Small intestinal distension on rectal palpation, or suspected distension based on other clinical findings. | Can be limited by lack of availability of equipment and/or experience in technique18. |

| Further information required to differentiate medical versus surgical conditions. | Gas distension causing acoustic shadowing can limit ability to image different structures. Combination of transrectal and transcutaneous techniques can be helpful19. | |

| Suspected surgical large colon lesions to determine treatment and prognosis. | Often have marked gas distension, but intestinal wall thickness can aid with decision making on prognosis20. | |

| Suspected peritonitis (as aforementioned) | Body condition score and coat thickness can affect image quality. | |

| Abdominal masses (as aforementioned). | Cannot image all of the abdomen, some areas may not be imaged and repeated examinations may be required in some cases21. | |

Decision making in donkeys

The majority of practitioners will only see a small number of donkeys as clinical patients. Significant differences exist in the clinical presentation and diagnostic approach recommended in donkeys with clinical signs of colic.

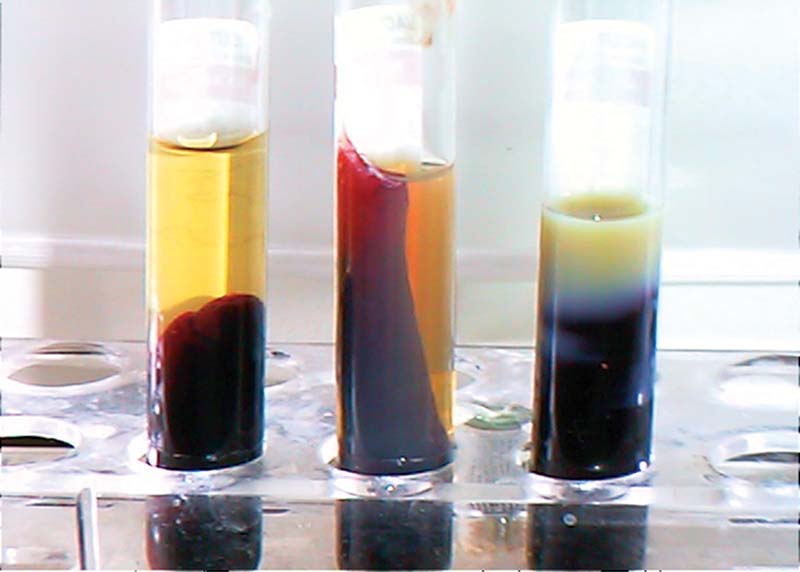

Hyperlipaemia is a common complication in donkeys19,20 (Figure 3).

Normal reference ranges for both clinical and biochemical parameters in the donkey differ from those in the adult horse21.

It is important these differences are recognised and considered in decision making in donkeys presenting with colic. Key aspects are summarised in Table 2.

| Table 2. Summary of key differences between the presentation and diagnosis of colic in the donkey compared to the horse | |

|---|---|

| Clinical signs of colic | • Clinical signs are more subtle than those in the horse – common signs are dullness, isolation and reduced appetite24. • Other signs include lack of ear movement and lowered head carriage. • Donkeys with colic may still maintain some appetite. • Signs such as flank watching, abdominal kicking and rolling are rare, and usually indicate a severe lesion24. |

| Physical examination | • Normal heart rate is 36bpm to 52bpm; a heart rate greater than 70bpm is indicative of severe disease and/or pain. • Normal respiratory rate is 12bpm to 28bpm and normal rectal temperature is 36.5°C to 37.8°C.l Abdominal ballottement and external palpation may be useful in smaller donkeys. |

| Diagnostic approach | • A rectal examination should always be performed. Spasmolytics, such as butylscopolamine, can be used at the standard equine dose rate. Impactions are a common cause of colic and the majority occur at the pelvic flexure22. • Hyperlipaemia is a common complication of colic in the donkey. Triglycerides levels should be assessed in any donkeys, which are inappetent and painful/dull24,25. • Blood results must be interpreted against normal values for donkeys – reference values for many parameters vary significantly from those in the horse26. • Clinical signs and haematology changes in response to hypovolaemia can be significantly less marked than in the horse. • Dental examination should always be performed as dental disease (especially diastema, or loss of greater than eight teeth) is a significant risk factor for impactions23. • Nasogastric intubation should be performed using a 9mm to 11mm nasogastric tube. • Ultrasound guidance can be useful for abdominocentesis as the intra-abdominal fat layer can be up to 8cm thick, even in animals that have a low body condition score. |

Conclusion

Although a wide range of options are available for diagnostic tests, only a small number of tests are required in most cases.

It is important to remember a definitive diagnosis is often not required and the primary aim should be to differentiate critical cases from mild medical cases.

Some key tests are often the simplest ones – in one survey of veterinary practitioners, “response to analgesia” was considered to be one of the main diagnostic tests4, followed by rectal examination and nasogastric intubation. Other diagnostic tests can be extremely valuable in identifying different causes of colic, or in cases where decision making can be complex and further information on optimal treatment and outcome are required.

However, the aspects of a case that determine our diagnostic approach and have the major effect on our decision making remain some of the simplest – the importance of patient history and physical examination findings cannot be underestimated.

References

- Curtis L et al, Burford JH, Thomas JS, Curran ML, Bayes TC, England GC and Freeman SL (2015). Prospective study of the primary evaluation of 1,016 horses with clinical signs of abdominal pain by veterinary practitioners, and the differentiation of critical and non-critical cases, Acta Veterinaria Scandinavica 57: 69.

- Proudman CJ (1992). A two year, prospective survey of equine colic in general practice, Equine Veterinary Journal 24(2): 90-93.

- Proudman CJ, Edwards GB, Barnes J and French NP (2005). Modelling long-term survival of horses following surgery for large intestinal disease, Equine Veterinary Journal 37(4): 366-370.

- Curtis L, Trewin I, England GC, Burford JH and Freeman SL (2015). Veterinary practitioners’ selection of diagnostic tests for the primary evaluation of colic in the horse, Veterinary Record Open 2(2): e000145.

- Archer DC, Pinchbeck GL and Proudman CJ (2011). Factors associated with survival of epiploic foramen entrapment colic: a multicentre, international study, Equine Veterinary Journal Supplement 43(s39): 56-62.

- Tinker MK, White NA, Lessard P, Thatcher CD, Pelzer KD, Davis B and Carmel DK (1997). Prospective study of equine colic risk factors, Equine Veterinary Journal 29(6): 454-458.

- Cohen ND (1999). Dietary and other management factors associated with colic in horses, Journal of the American Veterinary Medical Association 215(1): 53-60.

- Scantlebury CE, Archer DC, Proudman CJ and Pinchbeck GL (2011). Recurrent colic in the horse: incidence and risk factors for recurrence in the general practice population, Equine Veterinary Journal Supplement 43(s39): 81-88.

- Archer DC, Pinchbeck GL, Proudman CJ and Clough HE (2006). Is equine colic seasonal? Novel application of a model based approach, BMC Veterinary Research 2: 27.

- Edwards GB and Proudman CJ (1994). An analysis of 75 cases of intestinal obstruction caused by pedunculated lipomas, Equine Veterinary Journal 26(1): 18-21.

- Archer DC, Freeman DE, Doyle AJ, Proudman CJ and Edwards GB (2004). Association between cribbing and entrapment of the small intestine in the epiploic foramen in horses: 68 cases (1991-2002), Journal of the American Veterinary Medical Association 224(4): 562-564.

- Newton JR, Hedderson EJ, Adams VJ, McGorum BC, Proudman CJ and Wood JL (2004). An epidemiological study of risk factors associated with the recurrence of equine grass sickness (dysautonomia) on previously affected premises, Equine Veterinary Journal 36(2): 105-112.

- McCarthy HE, French NP, Edwards GB, Miller K and Proudman CJ (2004). Why are certain premises at increased risk of equine grass sickness? A matched case-control study, Equine Veterinary Journal 36(2): 130-134.

- Curtis L, Bayes TC, England GCW, Burford JH and Freeman SL (2014). Systematic review of risk factors for equine colic, Equine Veterinary Journal Supplement 46(s47): 21.

- Proudman CJ, Edwards GB, Barnes J and French NR (2005). Factors affecting long-term survival of horses recovering from surgery of the small intestine, Equine Veterinary Journal 37(4): 360-365.

- Nielsen JV (2007). Colic in horses: prognostic factors and indicators for referral, Dansk Veterinaertidsskrift 90(13): 22-29.

- Cullen TE, Curtis L, England GCW, Burford JH and Freeman SL (2015). Systematic review of evidence for plasma and peritoneal lactate as a diagnostic test for surgical colic, Equine Veterinary Journal 47: 5-6.

- Curtis L, Trewin I, England GC, Burford JH and Freeman SL (2015). Veterinary practitioners’ selection of diagnostic tests for the primary evaluation of colic in the horse, Veterinary Record Open 2(2): e000145.

- Freeman S (2002). Ultrasonography of the equine abdomen: techniques and normal findings, In Practice 24: 204-211.

- Sheats MK, Cook VL, Jones SL, Blikslager AT and Pease AP (2010). Use of ultrasound to evaluate outcome following colic surgery for equine large colon volvulus, Equine Veterinary Journal 42(1): 47-52.

- Williams S, Cooper JD and Freeman SL (2014). Evaluation of normal findings using a detailed and focused technique for transcutaneous abdominal ultrasonography in the horse, BMC Veterinary Research 10: S5.

- Cox R, Burden F, Gosden L, Proudman C, Trawford A and Pinchbeck G (2009). Case control study to investigate risk factors for impaction colic in donkeys in the UK, Preventive Veterinary Medicine 92(3): 179-187.

- du Toit N, Burden FA and Dixon PM (2009). Clinical dental examinations of 357 donkeys in the UK. Part 2: epidemiological studies on the potential relationships between different dental disorders, and between dental disease and systemic disorders, Equine Veterinary Journal 41(4): 395-400.

- Duffield H (2008). Colic. In Svendsen ED (ed), The Professional Handbook of the Donkey (4th edn), Whittet Books, Linton.

- Burden FA, Du Toit N, Hazell-Smith E and Trawford AF (2011). Hyperlipemia in a population of aged donkeys: description, prevalence, and potential risk factors, Journal of Veterinary Internal Medicine 25(6): 1,420-1,425.

- Burden FA, Hazell-Smith E, Mulugeta G, Patrick V, Trawford R and Brooks Brownlie HW (2016). Reference intervals for biochemical and haematological parameters in mature domestic donkeys (Equus asinus) in the UK, Equine Veterinary Education 28(3): 134-139.