23 Oct 2017

Peter Edmondson looks at how vets can work with farmers to effectively control and reduce infection on dairy farms.

Figure 2. The mastitis target rate is 30, but the UK average is somewhere between 40 and 50.

Mastitis articles appear in the vet and farming press on a regular basis and the tendency is for readers to switch off, as we have heard most of it before. So, a different slant will be put on this one.

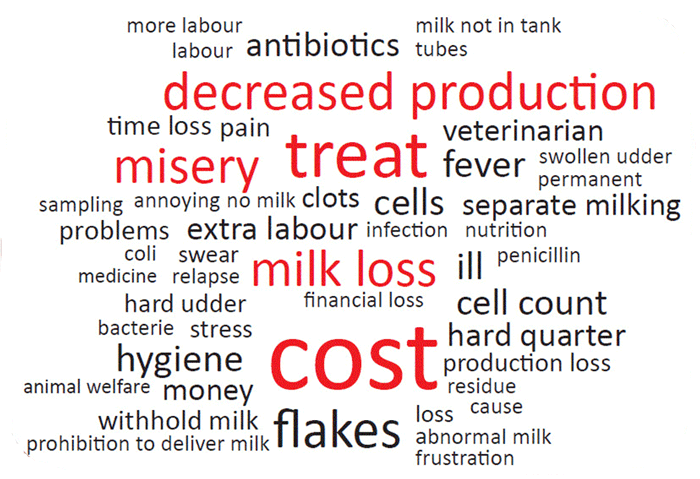

How do farmers feel about clinical mastitis? We make assumptions it’s all related to cost, but, in reality, there are far more factors that worry them.

Look at the “wordle” (Figure 1) – an interesting tool. Farmers were asked to write down words they associated with mastitis – the bigger the word, the more commonly farmers chose it. Of course, “cost” was a top hitter, but, look again, and you see words such as “misery”, “frustration” and “stress”, and you soon see the real emotional impact of this disease. Often, this can be far more distressing than the economic aspects.

A few years ago, I visited a herd in Northern Ireland that had a severe mastitis problem. The mastitis rate was more than 100 and when I arrived on the farm the atmosphere was heartbreaking. The stress on the family was immense. While the economic aspect of the disease was crippling, it was the emotional part causing the greatest concern. They dreaded milking, because they knew they were going to see more clinical cases and it was grinding them down.

So, if we want to connect with people and what causes them concern about anything, the most important thing is to ask them how they feel. You could ask “is mastitis okay now?”, but you will get a “yes” or “no” answer, which is of little use.

We need to ask key questions:

As vets, we often don’t ask open questions – such as who, what, when, where and why – but these can get a really good discussion going.

Let us return to mastitis. You have asked the farmer about how he or she feels. So, you can now ask about incidence. You could go through all the records or look on the computer, but, more often than not, farmers have a pretty good idea how many cases they have a week. Take this weekly figure, multiply by 52 for the number of weeks in the year, divide by the number of cows and multiply by 100, and you have the mastitis rate. This is a really useful comparison of incidence between herds, irrespective of herd size.

The target is 30, but the UK average is probably somewhere between 40 and 50 (Figure 2). However, many herds have levels of fewer than 20 that want to get this even lower. Is mastitis something the farmer is interested in looking at reducing?

It is important to explain the process and how you approach a mastitis problem. What will you need to do and why are you are doing it? For example, you will want to do data analysis to help quantify the disease more accurately, but, more importantly, this data has great value in helping establish the types of infection – contagious, environmental, dry or lactation period infections.

You will need to do a detailed farm visit, but why? The farmer might think you could take a quick look around and make some changes.

You need to know what is going on to work out how you can help improve the situation. You will stop using products or drop tasks if they have no benefit and replace these with things that work. Once the farmer understands the process and the time involved then the cost element makes sense.

The way you approach the visit is very important. It is wise to ask the farmer and his staff what they think is contributing to the problem, and what steps have been taken to rectify it. Which steps do they feel have been successful and which have been a waste of time? The last thing you want to do is make a recommendation for something that has already taken place and been unsuccessful.

You need to spend time finding out about the mastitis management, which you can do by asking “open” questions, but, more importantly, you need to spend time on the farm.

When I carry out mastitis visits, I always tell farmers the questions are like the Spanish Inquisition – asking lots of questions to find out exactly what is going on.

I want to stop carrying out tasks or using products that have no benefit, and replace them with things that will make an improvement. It is very important to explain to the farm team why you are making these changes. I call these “suggestions”, as if they feel they are not practical or will not work, there is little point in implementing them. Your powers of persuasion help here. We want the farm team to buy into the solution and understand why certain changes are being made.

An easy example would be the use of internal teat sealants. If a herd has more than 1 in 12 cows that get mastitis in the first 30 days of lactation, we know a problem exists with dry period infections. We need to encourage the farmer to use internal teat sealants at dry off, and, of course, this is an additional expense.

We need to tell the story about dry period infections and their importance, how these internal teat sealants work, the benefits they will see and work out a cost benefit. More importantly, we need to ensure people are properly trained in their use. Training is important to farm staff.

The best way to train is to explain what you want them to do, demonstrate the task or procedure then get them to demonstrate it back to you. We should reinforce training time and time again. This is particularly the case when we want to make changes to the milking routine, where milkers will have been used to their routine, often for many years, and it is a big thing to change to something different.

We need to put in monitoring methods to check we are making progress in the key areas. This might be monitoring records, milk buyers’ data, cleanliness of the milk sock and the length of time it takes to milk. We need to keep working with the farmer to achieve their long-term goal.

Always give a written report with the key points jotted down. Years ago, I used to prepare reports that were too long.

Remember, less is often more. Keep things simple.

A written report is also useful for reference. A farmer once contacted me because he was unhappy about the advice I had given two weeks earlier.

I visited the farm and went through the eight action items he had agreed to take. He had only done one of these, which was to order some internal teat sealant – which he had never used – and he had not culled the five cows he was going to cull immediately after my initial visit to reduce the herd cell count.

If you do not have a record of the advice you gave, you cannot keep track of what the farmer should be doing. Remember, farmers are busy people and forget what you tell them as soon as you drive off, as they are moving on to the next task on the farm.

I was at the Royal Association of British Dairy Farm Gold Cup Open Day in June and Ian Ohnstad, from The Dairy Group, gave a presentation about mastitis control on an award-winning farm.

Over a two-year period he worked with the farm team, including the vet, to drop the mastitis rate from 41 to 13, a 66 per cent reduction. He explained how he worked, how he used data and the importance of working as a team. He explained how he used data to measure success.

It was a powerful story and I could see other farmers were thinking if they had a mastitis problem, the person they would need to sort it out was Ian, who is not a vet.

You could do the same. Take a farmer, let’s call him Bill, where you have made a significant reduction in mastitis or cell counts. Invite him and a few others who have problems for a lunchtime meeting. You can talk for a few minutes, tell them a little about Bill’s story then let Bill take over. If he is a convert of how you worked, the other farmers will listen to what he is saying and he will be your ambassador.

There is no doubt cost is important. Significant financial benefits exist in reducing mastitis. It is a good idea to quantify this. Take Bill’s mastitis levels at the start, ask Bill how much each mastitis case costs and if it seems a reasonable figure – then use it. He can’t argue with his own figures. If his figures seem too low, go through costs with him to come up with a more accurate figure.

Work out how much mastitis is costing him. How much have you saved him? How much is this work per cow per year or in pence per litre (ppl)? How much did he have to spend to make this improvement? What is the cost benefit?

The good news is mastitis is easy to quantify.

Bill has 300 cows and had a mastitis rate of 60 or 180 cases for the year when you first visited. His mastitis rate has halved and you have saved him 90 cases.

Bill said each case costs him £200, plus headaches, so you have saved him £18,000 each year and he has never slept so well. He had to pay for your advice, some internal teat sealant and some other stuff, at a cost of £3,000. His return on the investment has been 600 per cent. This is equivalent to £60 per cow per year, about 60 per cent of vet and medicine costs, or equivalent to a milk price rise of 0.75ppl (Table 1).

| Table 1. Bill’s mastitis cost benefit | |

|---|---|

| Number of cows | 300 |

| Average yield | 8,000L |

| Number of cases in previous year | 180 |

| Number of cases a year later | 90 |

| Cost per clinical case (Bill’s figure) | £200 |

| Total saving | £18,000 |

| Saving per cow per year | £60 |

| Equivalent to a milk price rise | 0.75ppl |

Not many farmers would turn that down.

Did you work this figure out for Bill and tell him? Probably not, but it is important to do so to for two reasons. Firstly, to remind him of the success and, secondly, to demonstrate the value of your input. In addition, Bill is delighted as less disruption occurs in milking and his milkers find it far more enjoyable. You have been promoted to star status.

Clear and effective communication makes such a difference. It avoids so many problems that can occur with clients and people within the practice. We assume everyone is a good communicator, but are we? Or are there things we can do to become even better?