16 Dec 2025

Research into prevalence of myostatin in beef cattle herds

Kaz Strycharczyk MA, VetMB, MRCVS discusses his BCVA-funded investigations of this protein and attitudes towards it

Image: littlewolf1989 / Adobe Stock

A popular trope in genetics is the concept of a “gene for x”, where “x” is some trait of interest – growth, milkiness, fleshing, docility, fleece quality, fecundity and so on. These traits are almost always multigenic, so even if a gene is correlated with a trait, on its own it may be a poor predictor of phenotype.

There are exceptions: the gene for polling versus horned, for example. And then there are single genes, which, despite contributing towards a multigenic trait, have an outsized effect on the phenotype.

In 2024-25, with the generous assistance of the BCVA Research Grant, I have investigated the prevalence of, and attitudes towards, one of these genes in beef cattle: myostatin.

Myostatin – the ‘double-muscling’ gene

Myostatin is frequently dubbed as the gene for “double-muscling”, which requires two points of clarification.

First, “double-muscling” is not a doubling of muscle tissue and definitely not a duplication of each muscle; instead, it refers to an increase in muscling.

Second, myostatin is not a gene; it’s a protein. It is encoded by the MSTN gene, and the protein is also known as growth differentiation factor 8 (GDF8). Almost all animals carry two copies – one paternal, one maternal – and when this gene is expressed properly, the myostatin protein exerts an inhibitory effect on myocytes, thereby restricting muscle mass (Elliott et al, 2012).

The presumed benefit of this restricted muscle mass is that muscle is an expensive tissue to grow and maintain. In a closed system, unrestricted muscle mass would drain resources away from other important functions such as immunity, reproduction and cognition.

Variants exist in the MSTN gene, which reduce the expression of functional myostatin, leading to a functional myostatin deficiency; therefore, when one or both of an animal’s copies are affected, we see degrees of unrestricted muscle growth. Myostatin and its variants are found not only in mammals, but in birds, fish and even invertebrates (Rodgers and Garikipati, 2008).

In dogs, there is both the naturally occurring “bully whippet” phenomenon (Mosher et al, 2007), and the experimental CRISPR gene editing of beagles (Zou et al, 2015). In sheep, certain breeds are increasingly screening for MSTN using DNA marker tests (Talebi et al, 2022). In beef cattle, myostatin variants are diverse and prevalent (Ryan et al, 2023) – unsurprising given we have selected animals for muscularity using both visual appraisal and performance data. They generally have positive effects on growth and carcase traits (Esmailizadeh et al, 2008; Wiener et al, 2002; Wiener et al, 2009; Lines et al, 2009; Alexander et al, 2009; Cafe et al, 2014; Csürhés et al, 2023).

Unfortunately, myostatin variants are not a “free lunch” as, in a closed system, resources devoted to muscle must be diverted from some other function. These trade-offs include:

- Increased calving difficulty (Wiener et al, 2002; Arthur et al, 1988; Purfield et al, 2020; Konovalova et al, 2021).

- Increased perinatal mortality (Purfield et al, 2020).

- Reduced pelvic area (Arthur et al, 1988).

- Reduced internal organ mass (Fiems, 2012).

- Reduced voluntary feed intake (Fiems, 2012).

- Reduced milk production (Buske et al, 2011).

- Changes to milk fatty acid profile (Buske et al, 2011)

- Delayed puberty (Cushman et al, 2015).

- Increased sensitivity to psoroptic mange (Meyermanns et al, 2022).

- Less favourable sensory traits, such as flavour, tenderness, juiciness and toughness (Wiener et al, 2009).

To add another layer of complexity, there are many different myostatin variants found in domestic cattle, and these variants are found at varying frequency in different breeds (Dunner et al, 2003; Smith et al, 2000; Vankan et al, 2008). These variants do not behave identically to each other, with respect to the traits involved or the mode of impact (Ryan et al, 2023); for example, the F94L variant appears to confer carcase benefits without a corresponding increase in birthweight and, therefore, dystocia, and these benefits are additive depending on whether the animal is heterozygous or homozygous for the variant.

Compare this to the nt821 variant, which does combine increased birthweight and dystocia – except while the carcase benefits are additive, the dystocia element behaves as if partially dominant; that is, a modest increase in observed in heterozygous calves, with a considerably greater than double increase in homozygous calves.

Why I chose the topic

Our client base includes several progressive stud bull breeders and, with them, myostatin would crop up in pen-side conversations.

Interest piqued, I noted from time to time how the subject would be covered in the farming press. I noticed significant differences, first between breed societies; for example, some societies are eliminating variants from the herd book, some are encouraging certain variants over others, some are discussing myostatin while not taking an official view, and finally some are not talking about it at all. This discrepancy was mirrored at an international level; for example, a recent Teagasc webinar discussed how to optimise the use of myostatin variants in the suckler herd (Teagasc, 2025), while the American Angus Association describes its variant as a “genetic defect” (American Angus Association, 2011).

While I found ample literature pitched at an academic or breed society level, the resources aimed at extension level was comparatively rare, and the understanding among non-pedigree clients seemed patchy. Likewise, there was scant awareness and understanding among cattle vets, despite the multitude of important traits it affects.

So, while it is just one gene, myostatin does have a disproportionate impact on traits of interest. Bulls were a convenient proxy population, with several handling opportunities.

It also offered an opportunity to describe not just a genetic output, but a social one, too. Access to information on myostatin would not matter if it was not used at all, or if it was used ignoring the potential trade-offs.

The study

The project has two primary questions to answer.

1. What is the baseline prevalence of myostatin in beef stock bulls?

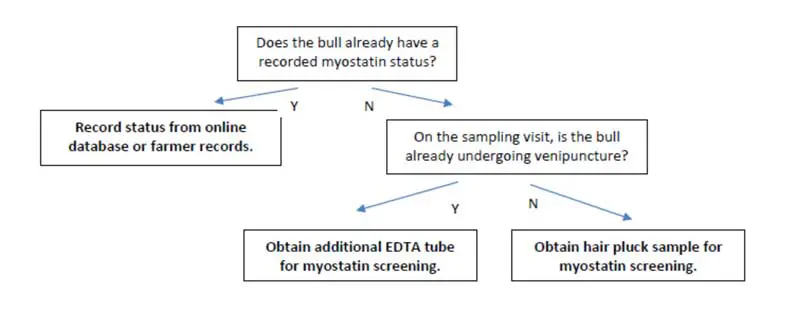

Bull ID was confirmed for each herd, and each bull was checked through online databases to confirm if any myostatin status was already recorded.

If no status was recorded, samples – either blood or hair – were taken from every stock bull the practice handled since the last year. To be eligible, the stock bull has to have sired calves born in 2024 and/or be siring calves for the 2026 crop. Sale bulls in specialist bull stud herds were excluded, as were fattening bulls. These have then been submitted to Neogen for myostatin profiling.

2. How do our clients use this information, if at all?

Around the time of sample collection, an eight-question survey was conducted with the client. This survey collected fundamental data about the individual, the farm business, and their awareness and use of myostatin status. This section was also open to beef farmers without breeding cattle.

The project is nearing the end of sample collection and data analysis is underway. However, several points have become clear already. First, myostatin variants can be found in nearly all breeds and not just those that exhibit obvious muscularity. Second, many bulls already have a recorded status. Finally, there is considerable variation in how clients use myostatin status, if at all; I expect to find a correlation between awareness and herd type (commercial suckler versus pedigree suckler).

Much of the data is descriptive, and so light on statistical analysis, but I will be investigating the relationship between the following factors:

- Age of farmer.

- Type of herd (pedigree versus commercial versus calf rearer versus grower-finisher).

- Herd size.

- Whether the farmer has any prior knowledge of myostatin.

- Whether the farmer knows the myostatin status of their bulls prior to checking/testing.

- Whether the farmer uses myostatin in any breeding or purchasing decisions.

- Prevalence of myostatin in the breeding bulls.

Research in practice

Our practice has been involved in on-farm research before, mostly as partners for data collection. A project like this was the logical next step and, while I look forward to answering the primary questions of the study, leading this project has led to several unforeseen and additional benefits.

The collection of basic data, the number of bulls on our clients’ farms; the bull:cow ratios, the breeds of bulls, the ages of bulls; the size of herds, and so on, has all been instructive. It allows for improved benchmarking and gives us a better understanding of “where” our clients are; for example, more than 50% of the stock bulls collected are Aberdeen Angus, with no clear second; I would never have guessed such a dominance of one breed. It also clearly demonstrates a client base that differs from the norm when compared to British Cattle Movement Service data (Smith, 2024).

It has also been a great entry for positive discussions on breeding decisions. In beef herds, our involvement is often initiated by a negative, such as a high barren rate, or excessive intervention at calving. We ought to take any opportunity to engage; for fans of the “HACCP” principle, bull selection is one of the critical control points – not just for myostatin status, but for polled versus horned, for structural phenotype, for temperament, for health status, and for the appropriate estimated breeding values.

Discussing myostatin has been an instructive practice in communicating a complex truth clearly; not to simplify, but to clarify. The distillation of complex ideas into simple messages is difficult, not least when you are trying to generate some meaningful advice for a specific client.

Finally, it has informed the logistics of future projects we hope to carry out. The responsibility of coordinating this from start to finish has already given me confidence to tackle issues I had been apprehensive about: ethical approval, project design, and grant application. I recommend the RCVS Ethics Review Panel for those pursuing a similar project.

- The author presented on this topic at BCVA Congress and wrote this article as a preview intended for the corresponding issue of Vet Times Livestock.

- The article appeared in Vet Times (2025), Volume 55, Issue 50, Pages 12-14.

Author

Kaz Strycharczyk graduated from the University of Cambridge in 2017. A native of north-east London, he had a short spell in Dumfries and Galloway, and joined Black Sheep Farm Health in Northumberland in January 2018 and its partnership in 2021. Kaz has helped coordinate a calving nutrition study with The University of Edinburgh, run various farmer education workshops, spoken to local farmers on how animal health is affected by stewardship, and built a practice database. He is currently studying towards a certificate in advanced veterinary practice (cattle).

References

- Smith B (2024). Beef market update: how have beef breed registrations changed in 2023, and how is this reflected on supermarket shelves?, AHDB, bit.ly/3MxDbod

- Alexander LJ, Kuehn LA, Smith TPL et al (2009). A Limousin specific myostatin allele affects longissimus muscle area and fatty acid profiles in a wagyu-Limousin F2 population, Journal of Animal Science 87(5): 1,576-1,581.

- American Angus Association (2011). Board nominees announced, ANGUSjournal, bit.ly/4914P5S

- Arthur PF, Makarechian M and Price MA (1988). Incidence of dystocia and perinatal calf mortality resulting from reciprocal crossing of double-muscled and normal cattle, Canadian Veterinary Journal 29(2): 163-167.

- Buske B, Gengler N and Soyeurt H (2011). Short communication: influence of the muscle hypertrophy mutation of the myostatin gene on milk production traits and milk fatty acid composition in dual-purpose Belgian blue dairy cattle, Journal of Dairy Science 94(7): 3,687-3,692.

- Cafe LM, McKiernan WA and Robinson DL (2014). Selection for increased muscling improved feed efficiency and carcass characteristics of Angus steers, Animal Production Science 54(9): 1,412-1,419.

- Csürhés T, Szabó F, Holló G et al (2023). Relationship between some myostatin variants and meat production related calving, weaning and muscularity traits in Charolais cattle, Animals 13(12): 1,895.

- Cushman RA, Tait RG Jr, McNeel AK et al (2015). A polymorphism in myostatin influences puberty but not fertility in beef heifers, whereas µ-calpain affects first calf birth weight, Journal of Animal Science 93(1): 117-126.

- Dunner S, Miranda ME, Amigues Y et al (2003). Haplotype diversity of the myostatin gene among beef cattle breeds, Genetics Selection Evolution 35(1): 103-118.

- Elliott B, Renshaw D, Getting S and Mackenzie R (2012). The central role of myostatin in skeletal muscle and whole body homeostasis, Acta Physiologica 205(3): 324-340.

- Esmailizadeh AK, Bottema CDK, Sellick GS et al (2008). Effects of the myostatin F94L substitution on beef traits, Journal of Animal Science 86(5): 1,038-1,046.

- Fiems LO (2012). Double muscling in cattle: genes, husbandry, carcasses and meat, Animals 2(3): 472-506.

- Konovalova E, Romanenkova O, Zimina A et al (2021). Genetic variations and haplotypic diversity in the myostatin gene of different cattle breeds in Russia, Animals 11(10): 2,810.

- Lines DS, Pitchford WS, Kruk ZA and Bottema CDK (2009). Limousin myostatin F94L variant affects semitendinosus tenderness, Meat Science 81(1): 126-131.

- Meyermans R, Janssens S, Coussé A et al (2022). Myostatin mutation causing double muscling could affect increased psoroptic mange sensitivity in dual purpose Belgian blue cattle, Animal 16(3): 100460.

- Mosher DS, Quignon P, Bustamante CD et al (2007). A mutation in the myostatin gene increases muscle mass and enhances racing performance in heterozygote dogs, Plos Genetics 3(5): e79.

- Purfield DC, Evans RD and Berry DP (2020). Breed- and trait-specific associations define the genetic architecture of calving performance traits in cattle, Journal of Animal Science 98(5): skaa151.

- Rodgers BD and Garikipati DK (2008). Clinical, agricultural, and evolutionary biology of myostatin: a comparative review, Endocrine Reviews 29(5): 513-534.

- Ryan CA, Purfield DC, Naderi S and Berry DP (2023). Associations between polymorphisms in the myostatin gene with calving difficulty and carcass merit in cattle, Journal of Animal Science 101: skad371.

- Smith JA, Lewis AM, Wiener P and Williams JL (2000). Genetic variation in the bovine myostatin gene in UK beef cattle: allele frequencies and haplotype analysis in the South Devon, Animal Genetics 31(5): 306-309.

- Talebi R, Ghaffari MR, Zeinalabedini M et al (2022). Genetic basis of muscle-related traits in sheep: a review, Animal Genetics 53(6): 723-739.

- Teagasc (2025). Breeding the ideal cow, Teagasc, Agriculture and Food Development Authority, bit.ly/4iJW8A6

- Vankan DM, Corley S, Wayne D and Fortes M (2008). Genotyping methodology and frequencies of the myostatin F94L mutation in Australian cattle breeds, 31st Conference of the International Society of Animal Genetics, Amsterdam.

- Wiener P, Smith JA, Lewis AM et al (2002). Muscle-related traits in cattle: the role of the myostatin gene in the South Devon breed, Genetics Selection Evolution 34(2): 221-232.

- Wiener P, Woolliams JA, Frank-Lawale A et al (2009). The effects of a mutation in the myostatin gene on meat and carcass quality, Meat Science 83(1): 127-134.

- Zou Q, Wang X, Liu Y et al (2015). Generation of gene-target dogs using CRISPR/Cas9 system, Journal of Molecular Cell Biology 7(6): 580-583.