30 Apr 2018

Volker Krömker looks at the identification of bacteria entering the mammary glands of cows, risk, prevention and therapy.

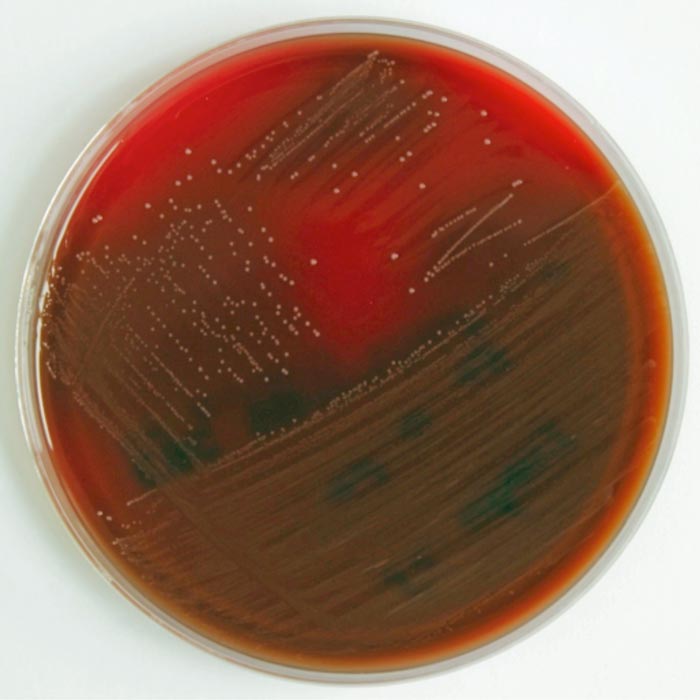

Figure 3. Growth of Streptococcus uberis on a blood agar plate.

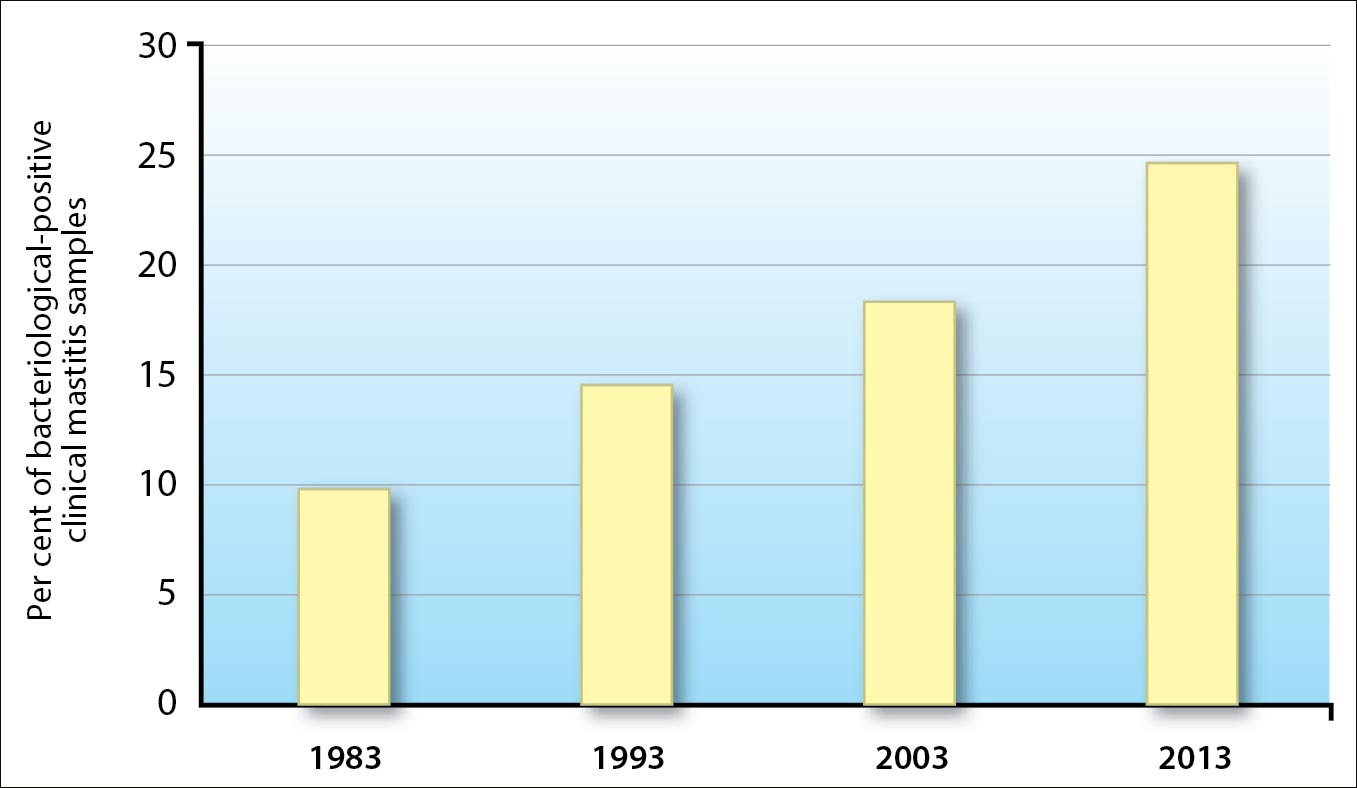

Improved management on modern dairy farms decreases the relevance of subclinical mastitis. However, clinical mastitis is still a common and costly disease on dairy farms all over the world (IDF, 2005; Hogeveen et al, 2011; Figure 1).

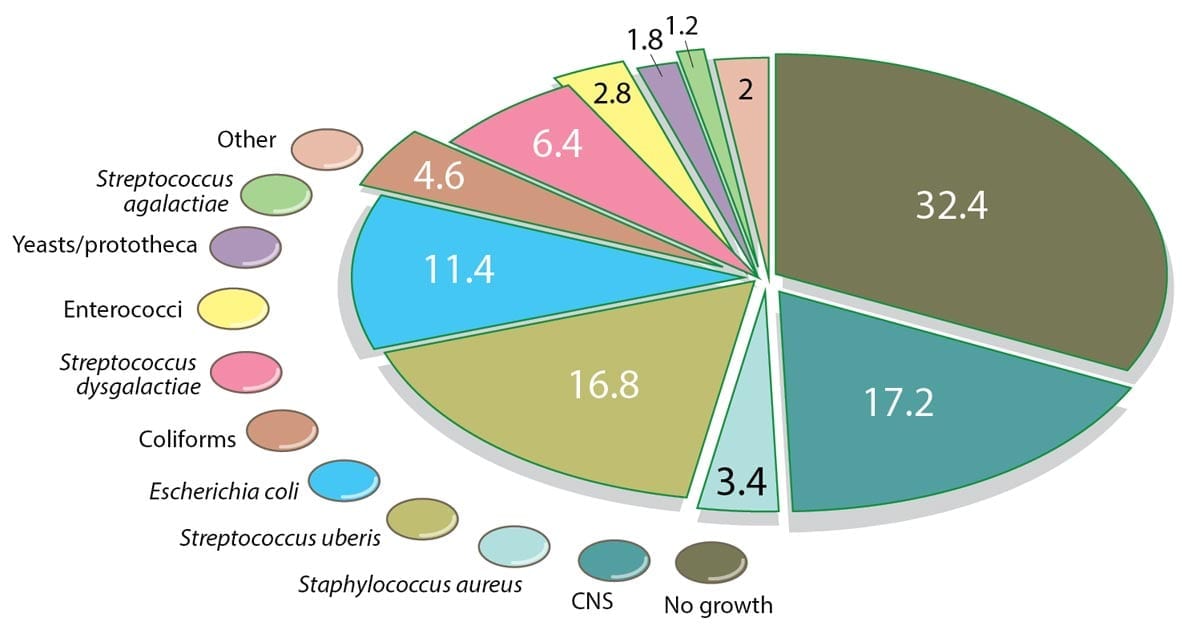

For several years, Streptococcus uberis has been the most important causative pathogen for clinical mastitis in many countries (Figure 2).

On blood agar plates, S uberis grows at 30°C to 37°C (Figure 3). Colonies have a diameter of 1mm to 2mm after an incubation period of 24 to 48 hours. Adding 0.1% aesculin to the medium enhances bacteria identification, as S uberis and enterococci hydrolyse aesculin to glucose and aesculetin. Examination under UV light confirms this reaction.

At present, many routine laboratories do not selectively differentiate S uberis. Due to the rising cost pressure of high frequency analyses – such as the microbiological investigation of quarter foremilk samples for mastitis pathogens – identification is often limited to aesculin-hydrolysing streptococci, failing to differentiate S uberis and enterococci or to identify aesculin-negative streptococci.

Several virulence factors are known for S uberis. However, considerable differences exist in the exhibition of virulence factors between the various isolates. Biofilm formation is an important virulence factor that may cause recurrent or persistent mastitis by impairing the host immune defence and through the protection of antimicrobial substances.

Almost 100% of S uberis strains are able to produce biofilms in vitro. Moreover, the enzymes produced by S uberis seem to play a decisive role in the distribution of infections with this pathogen, which is able to impede the proper development of the mammary gland and induce the formation of capsules in the tissue.

S uberis is a ubiquitous microorganism that colonises animals as well as their environment. Environmental streptococci are responsible for around one third of all clinical mastitis cases. The pathogens enter the mammary gland via the teat canal. High pathogen levels in the animals’ environment increase infection rates. Zadoks et al (2005) found S uberis was present in 63% of environmental samples (earth, vegetable material and bedding), in 23% of faecal samples and 4% of milk samples.

During summer (grazing season), contamination rates in bovine faeces are higher than in other seasons. Straw and other organic bedding material enhance the growth of S uberis. If several cows in the same herd are infected it is quite unlikely all the infections are caused by an identical S uberis strain. Udder infections – which are caused by one dominant S uberis strain – tend to persist on farm for a longer period than udder infections caused by a multitude of strains. Most infections do not last for long periods (16 to 46 days).

The cases of clinical mastitis caused by S uberis are clearly associated with hygiene (cleanliness and dryness) in husbandry, feeding and machine milking. S uberis infections of the mammary gland can occur during the dry period (evaluation of the new infection rate in the dry period) and often develop an acute course in the following lactation. Straw and other organic bedding materials promote the growth of S uberis.

Udder quarters that have recovered from infection with S uberis or other microorganisms exhibit an elevated risk of reinfection. Research has shown S uberis mastitis is often followed by recurrent S uberis mastitis cases. Strain typing techniques have shown most of these cases are new infections. Often misinterpreted as unsuccessful treatment, recurrent mastitis cases show it is not the treatment that is the problem, but the fact an infection increases the risk of new infections.

An intramammary infection is initially preceded by contamination of the teats or the udder surface, whereby in indoor housing the risk of contamination during the inter-milking periods is determined by the design of the lying surfaces, the space per cow, the bedding material, and the frequency of bedding addition, cleaning and disinfecting, as well as the cows´ length of stay in the cubicles.

The fact the rate of infection with environmental mastitis is highest during the summer months accounts for increased bacterial counts in the bedding material. The indicator for the optimisation effort in hygiene of the resting area is the cleanliness of the teats. The objective should be for more than 90% of the animals to have only a few coarse dirt particles on the teats, which can be removed by wiping with a disposable towel or something similar. Feeding imbalances, as well as fluctuations in the dry matter intake of the animals, seem to be associated with the exacerbation of clinical S uberis mastitis.

Machine milking can lead to the invasion of S uberis into the glands, which can be avoided by carefully cleaning the teats prior to milking. This can, but does not have to, be carried out by means of disinfecting measures before milking. A crucial point is about 95% of the teats leave no, or only slightly yellowish, residues on the disinfecting cloth with which they have had contact before the milking clusters are attached.

Usually, S uberis is sensitive to penicillin preparations and other ß-lactams, and the minimum inhibitory concentrations of penicillin preparations and other ß-lactams are low for S uberis. Several studies have shown an extension of the therapy period up to eight days is useful to increase the bacteriological cure rate (especially in young animals). The administration of oxytocin, or performing additional milkings, is not recommended, as these measures additionally increase the proliferation rate of S uberis in the mammary gland.

The successful treatment of intramammary infections caused by S uberis is crucial in the dry period (including the use of antibiotic dry cow therapy and the prevention of such infections – with teat sealer, hygienic husbandry conditions, control of hypocalcaemia and avoiding loss of body mass during the dry period) and lactation.

S uberis is one of the most important causative pathogens for clinical mastitis in many countries around the world and responsible for a third of all clinical mastitis cases. S uberis is known for a set of virulence factors, including biofilm formation. It is a ubiquitous microorganism that colonises animals, as well as their environment.

Cases of clinical mastitis caused by S uberis are clearly associated with hygiene (cleanliness and dryness) in husbandry, feeding and machine milking. (Extended) antibiotic therapy is effective, but is usually followed by new infections – often with another S uberis strain. An effective vaccine that primarily reduces the clinical exacerbation would be of great benefit.