4 Mar 2019

The dry cow period – what vets should be monitoring

Sophie Mahendran considers the need for cattle to be well cared for during this time, including nutrition and maintaining hygiene.

Figure 2. Dry cows housed in a loose-bedded straw yard.

The dry period is the time when dairy cows are no longer lactating and makes up one section of their productive life cycle – the others being the fresh/transition period, peak lactation and mid-to-late lactation.

While each period comes with its own challenges and key areas of focus, the dry cow tends to be considered as the least management intensive. Although this is partly true, in that day-to-day maintenance is generally low input, the effects of getting the dry period wrong can have significant detrimental impacts on the cow’s future lactation (Figure 1).

Length

The length of the dry period is usually around eight weeks, and it is a time during which mammary cell proliferation rate is at its highest, allowing renewal and regeneration of the gland ready for the next lactation (Sorensen et al, 2006). This includes the opportunity for the cow to resolve any existing intramammary infections, as well as trying to prevent any infections establishing.

A relatively large body of work has been built assessing the merits of different lengths of dry period, with both shortened and extended times investigated. Some merits appear to exist in a shortened dry period, with positive impacts on the energy levels and metabolic health post-calving (Andrée O’Hara et al, 2018), as well a higher overall lactation yield prior to dry off, which can be very significant in high-yielding cows (Bernier-Dodier et al, 2011).

Shorter dry periods can also help reduce the occurrence of milk fever in grazing cattle by giving a less profound drop in blood calcium levels (Saborío-Montero et al, 2017). This may be helpful for managing herds made up of particularly susceptible breeds, such as Channel Island breeds.

However, decreasing the length of the dry period to less than 40 days has been reported to drop milk yield in the subsequent lactation, and omitting the dry period completely drops the milk production levels following parturition. This may be due to a lack of replenishment of body reserves to supply the energy required for a rising plane of milk yield, along with an interference in the mammary glands preparation and repair for the next lactation (Bernier-Dodier et al, 2011; Figure 2).

Mastitis

Approximately 40% to 50% of clinical mastitis infections detected during lactation occur due to infections picked up during the dry period, resulting in reduced milk production and financial losses (Bradley and Green, 2000).

Many of the risk factors for intramammary infection are subsequently discussed in detail, but include appropriate drying off protocols, environmental hygiene and transition cow management being crucial.

Both Gram-positive (for example, Streptococcus uberis) and Gram-negative (for example, Escherichia coli) infections may be picked up during this time, with infections having the ability to lie dormant within the udder until lactation recommences (Bradley, 2002).

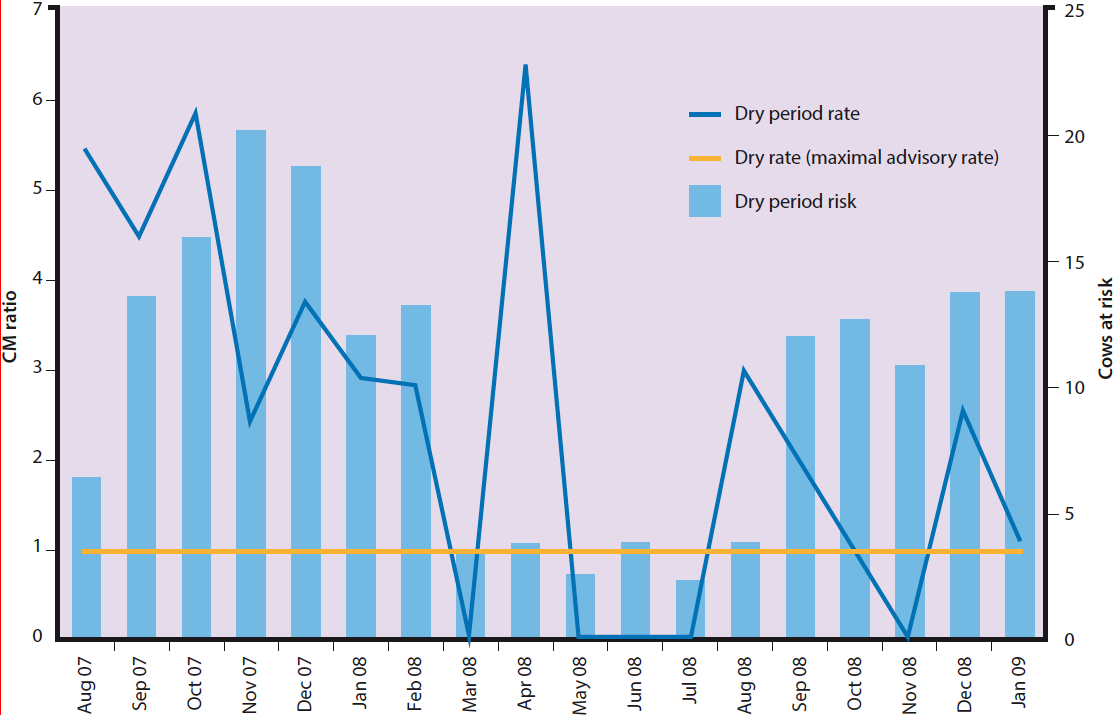

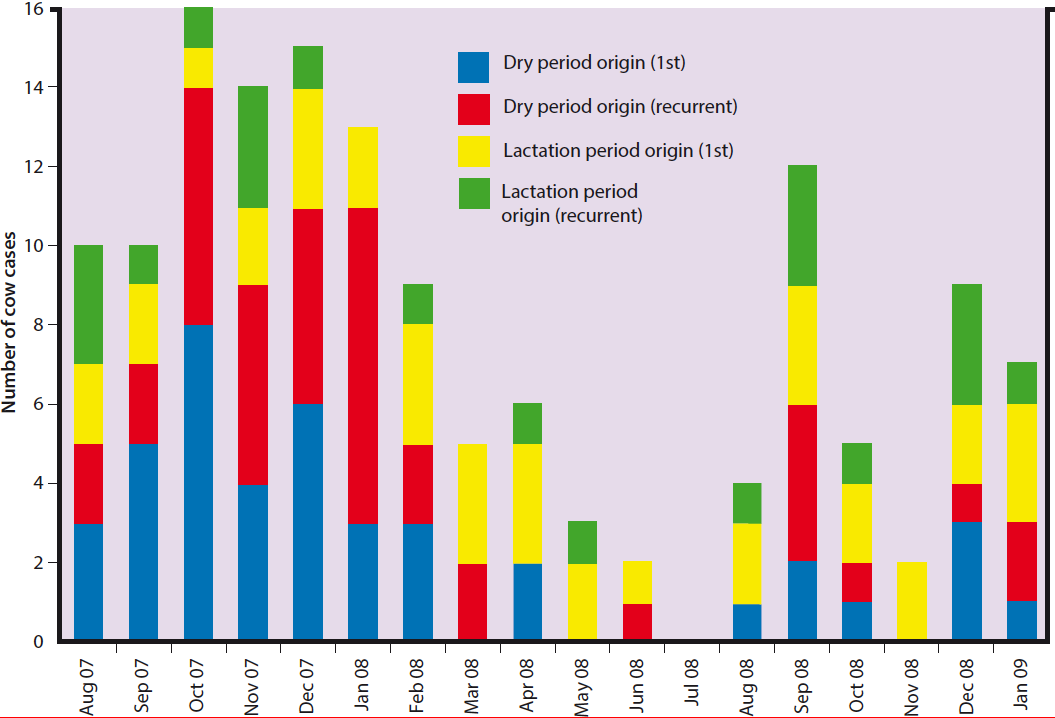

Careful analysis of clinical mastitis records can alert the clinician to problems originating during the dry period. Development of clinical mastitis within the first 30 days of lactation are indicative of a dry period origin, with some E coli mastitis cases that result from the dry period occurring up to 100 days into a lactation (Bradley and Green, 2001).

Use of readily available software produces easy-to-interpret graphs that can help with identification of dry period origin mastitis cases (Figures 3 and 4).

Drying cows off

The start of the dry period can be a challenging time for cows, with the cessation of milk production often associated with animal discomfort due to milk accumulation and increased udder pressure.

This is seen as a decrease in lying times – especially in heifers (Rajala-Schultz et al, 2018). An analysis of data regarding the development of intramammary infections during the dry period may indicate changes need to be made to the drying off protocol.

The best way for a vet to check how well cows are dried off is to watch farmers during the process to get a true picture of the condition of the cows and methods employed. The first thing to check is the yields of the cows being dried off – animals still giving more than 15L of milk are at increased risk of developing intramammary infections due to milk leakage post-dry off, and a lack of keratin plug production. This increases the risk of microorganisms colonising the udder.

One way to combat this is by implementing a gradual cessation of milking by reducing parlour visits to once daily for the five to seven days prior to drying off (Zobel et al, 2013), and feeding a lower energy diet with removal of any concentrates in the diet for two weeks prior to drying off. This reduction in milk yield is important as for every extra 5kg in milk yield above 12.5kg on the day of drying off, the odds of a cow having an intramammary infection at calving increases by 77% (Rajala-Schultz et al, 2018).

The withdrawal of Velactis, which contained the prolactin inhibitor cabergoline, has left a gap in the market for products to aid in the cessation of lactation. One such product trying to fill this requirement is an oral bolus. It is designed to be administered at the time of drying off and contains anionic salts, which transiently alters the pH balance of the blood; resulting in reduced lactose synthesis and, therefore, milk volume production in the udder.

Suitable use of selective dry cow therapy is another area that can be monitored as it is important for both individual animal mammary gland health, as well as on the herd and country level, in terms of reducing antibiotic usage.

Interrogation of farm mastitis records can ensure the criteria used to identify cows that receive internal teat sealant only at drying off are appropriate, through assessment of somatic cell count levels and cases of clinical mastitis. Additional monitoring of a client’s compliance with their use of selective dry cow therapy can be made through analysis of the number of antibiotic tubes purchased compared to cow number in the herd.

Housing and nutrition of dry cows

Clean housing during the dry period, but particularly just after drying off and at calving, are fundamental for udder health, as these are the biggest risk periods for picking up new intramammary infections.

Spreading bedding evenly around a calving pen has been shown to be a cost-effective mastitis intervention (Down et al, 2016), or, if dry cows are kept outdoors during the summer period, appropriate pasture management must be upheld in a similar way to housing management. This includes ensuring paddocks are not grazed for more than two weeks at a time, then are rested for an additional four weeks before being used again (Green et al, 2007). This helps reduce the microbial contamination on the pasture.

No matter the housing type, ensuring dry cow pens are not overstocked is important, not only to reduce detrimental effects of stress on the immune system, but also to maintain food intakes prior to calving.

Ensuring appropriate nutrition for dry cows can have a positive impact on the health of the dry cow, as well as ensuring her transition back into lactation is as smooth as possible. The energy requirements for a dry cow are fairly minimal in comparison to a lactating one, needing only around 10% of her bodyweight in MJ/day, plus an additional 15 megajoules (MJ) to 20MJ for the growth of the fetus. For a 600kg dry cow, this works out as approximately 75MJ to 80MJ of metabolisable energy a day, compared to the same cow at peak lactation (approximately 50L) requiring 335MJ of metabolisable energy a day (based on needed 5.5MJ/L milk produced).

This 75% reduction in energy requirement means it is very easy to overfeed dry cows. Ensuring they receive high quality roughage to maintain rumen fill while limiting energy supply is essential. As mentioned previously, many farmers will turn dry cows out over the summer, but, ideally, this should be on to pastures of lower quality to limit excessive energy intakes. Monitoring and comparison of body condition score at dry off and calving will help identify if energy intakes over this period are appropriate.

Transition period

The last hurdle in the dry period prior to a cow re-entering the milking herd is the safe navigation of the transition period, which is the three weeks immediately prior to calving.

This part of the dry period is crucial for the prevention of metabolic disorders, and requires careful transition of the cow’s diet so she is physiologically prepared for calving and lactation. Assessment of health records for the number of cases of hypocalcaemia (target less than 5%), retained fetal membranes (target less than 5%), metritis (target less than 5%) and endometritis (target less than 10%), and displaced abomasa (target less than 2%) will indicate the success of management strategies.

Calcium homeostasis has a major impact on all these diseases, so ensuring suitable use of either a partial or full dietary cation-anion balance (DCAB) diet, or use of a calcium binder, will be required. DCAB diets work by acidifying the cow, which is known to increase blood calcium concentrations. Diets should aim to have a balance of -50 milliequivalents per kg (mEq/kg) to -100mEq/kg, along with feeding of low calcium roughages, such as straw and maize (Figure 5).

The use of a calcium binder, such as zeolite, is the other option for calcium management. It works by binding calcium contained in ingested feed, therefore preventing its absorption in the intestine. Although this method of calcium control is more expensive, it has demonstrated excellent effectiveness in trials and does not require sourcing of low calcium or potassium forages to feed along side it (Thilsing-Hansen and Jørgensen, 2001), therefore making it a more suitable option for some farmers.

Conclusion

The dry cow period is a time for cattle to relax from the high metabolic demand lactation requires – allowing the cow’s mammary tissue to remodel and repair, and offering some rest from the daily routines of the milking herd.

Ensuring these cattle are well catered for in terms of their hygiene and nutrition is very important in laying the foundations for a successful next lactation, with careful monitoring of mastitis and health records allowing vets and farmers to identify areas for improvement during this dry period.