5 Aug 2021

Understanding farmer attitudes towards delivering targeted lactation therapy

Andy Biggs will be stranger to few in the farm veterinary sector, and has been busy working on a mastitis project. He stepped into the <em>Vet Times</em> Examination Room to tell us all about it…

POSITION: Director at The Vale Veterinary Group, Tiverton, Devon.

BRIEF CV: I run The Vale Veterinary Laboratory, processing mainly milk and bedding samples, and have authored and co-authored many scientific papers and articles, and written a book, Mastitis in Cattle. I am a fellow of the RCVS, and a past-president of the World Cattle Veterinary Association and BCVA. I was awarded the Dalrymple-Champneys Cup and Medal by the BVA in 2015. I lecture widely around the world to farmers, students and vets, and am the sole tutor for the master’s mastitis module at Massey University School of Veterinary Science in New Zealand.

LITTLE-KNOWN FACT: My enjoyment of sailing dinghies, and more latterly yachts, might be in my blood, as my ancestry includes two admirals in the First World War. One was Royal Navy naval attaché in Berlin to Germany, Denmark and the Netherlands and was on the committee that designed the Dreadnought, with its revolutionary huge and numerous big calibre guns and steam turbine propulsion. The other captained HMS Warrior at the Battle of Jutland.

Q

What were the main aims of the study?

AThe aim of the study was to evaluate targeted lactation cow therapy (tLCT) and to understand farmer attitudes to delivering it.

It goes without saying that the best way to reduce antibiotic use is to reduce disease, so clearly the usual attention to the cow’s environment, nutrition, milking routine and machine maintenance are a given. tLCT aims to target antibiotics to those mastitis cases that will benefit from antibiotic therapy.

NSAIDs can, in my opinion, be justified for all mastitis cases, but nowadays we must question whether treatment always needs to include antibiotic tubes.

I think this study shows that mild or moderate (grade 1 or grade 2) coliform clinical cases, many of which may be no growths by the time they are detected, will respond well to an NSAID-only approach; antibiotics can be targeted at Gram-positive cases.

Q

Can you describe the format of the study?

ABaseline data was collected over 10 months for each herd while they were using conventional treatment (CT), where all clinical mastitis was treated with antibiotic.

The herds were commercial dairy herds in northern Germany, with between 175 and 650 cows, annual yields of 9,500 to 12,200 litres, and bulk milk somatic cell count (SCC) between 200 and 300,000 cells/ml.

Following the initial CT phase, the tLCT concept was introduced.

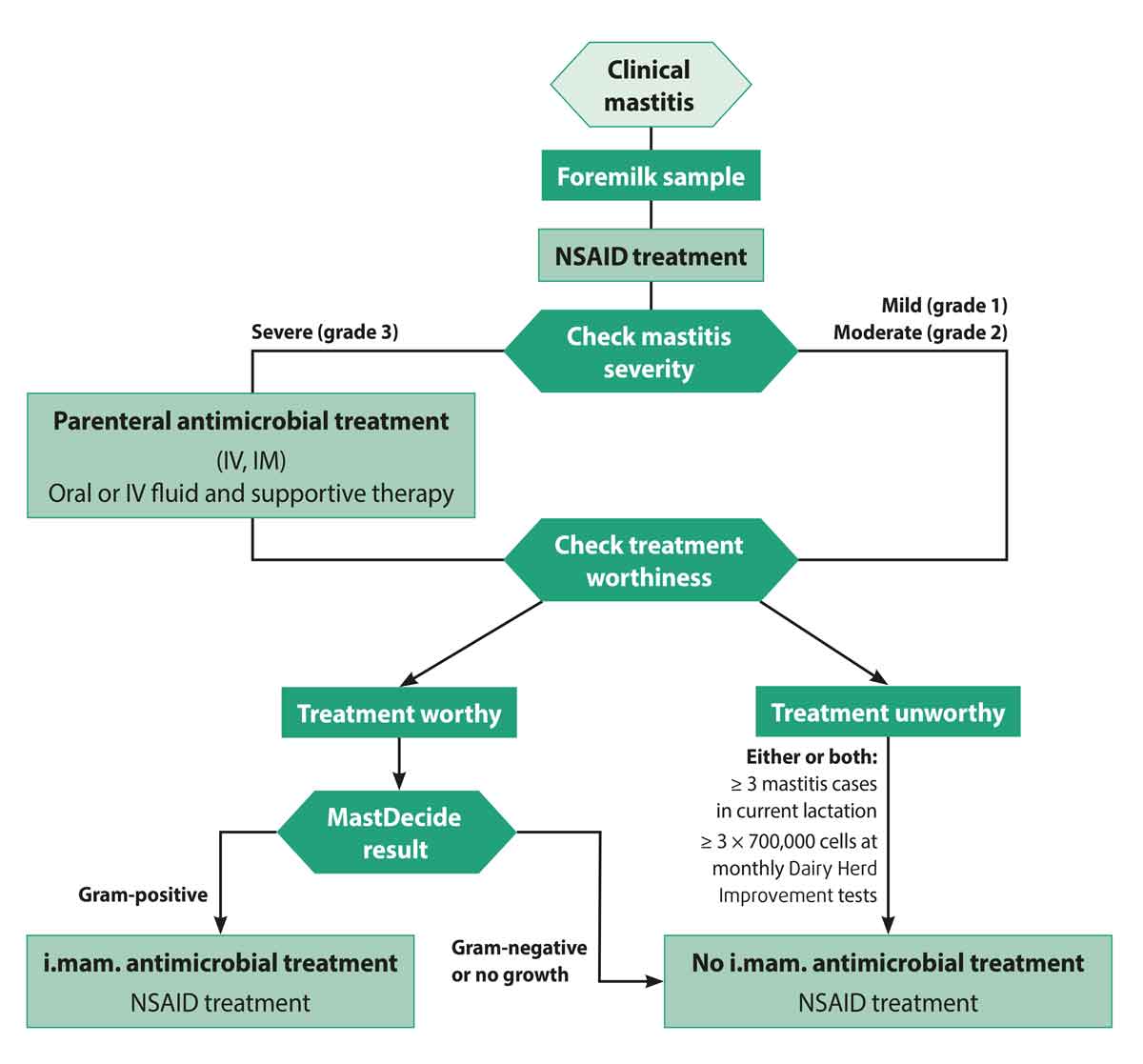

Cows are treated using a decision tree, with three variables to consider:

- clinical appearance – clinical mastitis severity score

- animal-related factors – individual cow SCC and clinical mastitis history

- pathogen-related factors – Gram‑positive, Gram‑negative or no growth

On identification of a case of mastitis, an aseptic milk sample was taken and each cow receives NSAID treatment. Cows with severe mastitis (grade 3) also received immediate systemic antimicrobial therapy and supportive fluids.

Those with grades 1 or 2 mastitis wait for the results of on farm culture (OFC) using a test kit (MastDecide) to identify Gram‑negative, no growth or Gram‑positive test results; this normally takes around 12 to 14 hours.

Cows with three consecutive high SCC scores (higher than or equal to 700,000 SCC/ml) in the previous three monthly milk recording (Dairy Herd Improvement) data, or with three or more clinical mastitis cases in the current lactation, were classified as “treatment unworthy”.

Once the test has been read, “treatment‑worthy” cows with Gram‑positive test results receive intramammary antimicrobials, while those with Gram-negative test results or no verified bacterial growth, or cows deemed “treatment unworthy”, remain on NSAID treatment alone.

In cows having an index (first) clinical mastitis case in their first to third lactation with a Gram‑positive test result, an extended local treatment is recommended (see flow chart).

Cure rates during the CT and tLCT phases were compared. A third category of tLCTmod was analysed where farmers decided to deviate from the tLCT concept.

QWhat do you mean by an extended local treatment, and why focus on first cases in young cows for extended treatment?

ABy identifying those cows that really need antibiotics, you can use a relatively long, on-label course of treatment to ensure those first cases in young cows don’t eventually become treatment‑unworthy cows.

Three to five days of an intramammary narrow‑spectrum European Medicines Agency category D antibiotic, such as penicillin, would be a suitable choice.

Q

How can vets support farmers in changing their approach to mastitis therapy?

A

Vets can support farmers in several ways:

- Demonstrating how a cow-side test with rapid results enables you to formulate a treatment plan that is based on evidence.

- Setting expectations for treatment or non‑treatment and expected outcome.

- Having a discussion with the farmer to contextualise the bigger picture of antimicrobial resistance and responsible antibiotic use.

- Evidencing increased profit by reducing antibiotic use, discarded milk and risk of antibiotic failures, especially when “tubing until the clots have gone” results in unnecessary prolonged cascade use of tubes with extended milk withholds in mild or moderate Gram‑negative or no growth cases where the inflammation will often – if not always – outlast the infection and the cases would respond to NSAID only.

However, it is worth remembering that the tLCT approach will not be right for all farms and taking a clean sample is critical, so be selective with those you choose.

Some vets worry they will be out of the loop with OFC; however, as all clinical mastitis cases are sampled to run the OFC, it is easy to store those samples in the freezer and culture in a commercial laboratory, giving better data than asking for clinical samples when an outbreak occurs.

Q

What sort of farms are most suitable for tLCT?

AIn my experience, it is more about the farmer wishing to use tLCT than any particular herd or cow characteristics. Although if a herd has a high bulk tank SCC it would be expected to have a high incidence of Gram‑positive clinical cases, and so a delay to antibiotic treatment could have a negative impact on cure rates.

If most cows are grade 3 “sick cows” or a high incidence of Staphylococcus aureus clinical cases are present, more important changes may be required than introducing tLCT and OFC.

I would do two things before using tLCT:

- Sample 5 to 20 clinical cases, depending on herd size, to check Gram‑positive and Gram‑negative incidence. If very high Gram‑positive rate then perhaps OFC is not for those farms.

- If tLCT is undertaken, I suggest checking 5 to 20 cases in a commercial laboratory to ensure the farmer is getting the right results.

Q

Do you have any practical advice on how to manage treatment‑unworthy cows?

AThe “treatment‑unworthy cows” concept is perhaps something to consider after farms have become confident using the tLCT concept.

A good cure rate will never be achieved with these cows, yet farmers often like to keep trying, especially if they are a particular favourite.

Treatment‑unworthy cows are just given NSAID as they will often clinically cure, but not bacteriologically cure even if given extended antibiotic treatment. Options are to dry off quarters or cull the cow in the long term.

Q

What results did the study deliver?

AIf antibiotic doses are given in accordance with the treatment concept, as much as 73 per cent of antibiotics could be saved in the tLCT group in comparison to the CT group.

Despite the treatment recommendations not being fully implemented in the tLCTmod group, about 62 per cent fewer intramammary doses were used.

The cure rates achieved in all three groups (CT, tLCT and tLCTmod) were broadly similar despite variations in labour input, tube use and cost.

Since the tLCT concept includes an NSAID treatment of all animals with clinical mastitis, more NSAID doses were administered in the tLCT group compared with the CT group.

Q

Farmer compliance was also recorded. What did that look like?

AIn more than half of the cases in the study, farms deviated from the treatment scheme, mainly by waiving the NSAID treatment or by treating treatment‑unworthy cows with antibiotics – this formed the tLCTmod group. In my experience, it can be difficult to persuade farmers not to treat treatment‑unworthy cows; however, significant antibiotic reductions are still achieved.

QWhat is the main take-home for the vet who may be undertaking a mastitis visit on a client’s farm later this week?

AProbably to be comfortable with the concept of evidence-based mastitis therapy and be aware that cows are getting better despite tubes on many occasions.

By combining an on‑farm rapid test with NSAID use for all clinical mastitis cases – and an understanding of mastitis severity and targeting antibiotic therapy to cows that will benefit – antibiotic use can be reduced and refined, and appropriate cure rates delivered.