22 Jul 2025

Why calf scours is still farm issue and how to help change narrative

Anna Bruguera Sala DVM, MVM, MRCVS discusses a key concern in the lives of young cattle, including guidance on colostrum

Image: ehasdemir / Adobe Stock

Diarrhoea is one of the main health and welfare concerns in calf management (Mee, 2023).

In 2018, a UK-wide survey found that 82% of farmers had experienced cases of calf diarrhoea in the previous year, and 48% had lost calves as a result (Baxter-Smith and Simpson, 2020). Similarly, Johnson et al (2017) reported diarrhoea morbidities in dairy herds ranging from 24.1% to 74.4% (48.2% average), highlighting the widespread and variable nature of the issue.

The consequences of calf diarrhoea extend beyond short-term illness. Affected calves are more likely to suffer from reduced growth rates, increased disease susceptibility, and later-life issues, including impaired fertility and reduced milk yields (Abuelo et al, 2021; Goh et al, 2024). As the future of the herd, every calf lost or compromised due to diarrhoea represents a potential gap in replacement rates and has a knock-on effect on long-term productivity.

Despite decades of research, including vaccine development that started in the 1950s (Maier et al, 2022), diarrhoea remains endemic in many herds. Why does it persist? This article explores some of the reasons and outlines updates in colostrum management, treatment and prevention to help change the narrative around calf diarrhoea.

Why is calf diarrhoea still an issue?

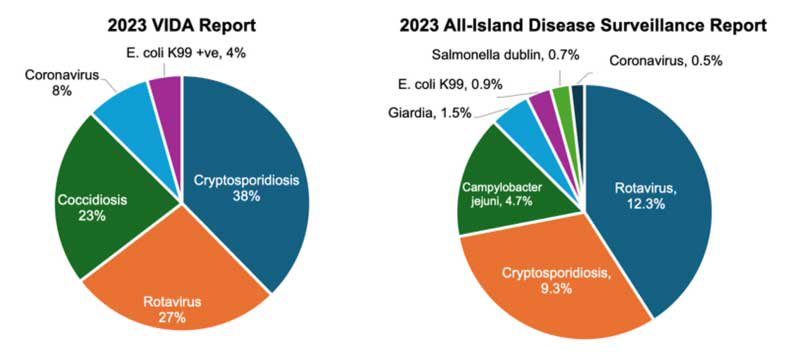

Calf diarrhoea is a multifactorial disease, with both infectious (for example, Escherichia coli, rotavirus, coronavirus, Cryptosporidium parvum) and non-infectious (for example, nutrition, abomasal conditions or ruminal drinking) causes (Denholm, 2025; Tilling, 2018). The most common diarrhoea pathogens diagnosed in Great Britain and Ireland are summarised in Figure 1 (APHA, 2023; DAFM and AFBI, 2023), although the actual pathogen prevalences may vary, as diagnostic tests performed in the field, in practice or those submitted to private laboratories are not included in national surveillance reports.

Morbidity and mortality rates associated with calf diarrhoea also vary significantly between farms, based on calf management practices such as colostrum and nutrition protocols, housing, hygiene, other co-morbidities and stress levels.

Therefore, addressing calf diarrhoea requires more than just treating symptoms or focusing solely on pathogens: it demands a holistic, farm-specific approach. Veterinary involvement is essential not only in diagnosing and treating affected calves, but also in guiding improvements in calf-rearing protocols, environment and preventive health planning. However, how effective these measures are will depend on the farmers’ attitudes and motivations towards calf health.

Baxter-Smith and Simpson (2020) noted that despite a high number of farms reporting cases of diarrhoea (82%), farmers did not always contact their vet for advice. Additionally, when asked what areas they wanted to improve the most on their farms, only 4% mentioned calf diarrhoea. This highlights the need for better client communication and education (Payne and Gladden, 2024) and shows potential room for improvement in the reporting and diagnosis of cases, in both dairy and beef herds.

Although a vet visit may not always be necessary for every case of diarrhoea, veterinary oversight and input are essential to ensure that both individual treatments and wider disease control measures are applied correctly.

What can be done to change the narrative?

Although the fundamentals of calf diarrhoea management have remained consistent over time (Gull, 2022; Heller and Chigerwe, 2018), a few recent developments and new calf health research offer improved tools to support prevention and control strategies.

Farmer engagement

As highlighted by Baxter-Smith and Simpson (2020), work still needs to be done in engaging farmers in managing calf diarrhoea. Mahendran et al (2021) also found that only 1.4% of farmers regularly involved their vet in calf health decision-making. A Vet Times article by Payne and Gladden (2024) provided advice on how to effectively communicate the diarrhoea message to clients. In practice, regular conversations with farmers, proactive herd health planning meetings and client events and training sessions are all opportunities to share knowledge and improve engagement.

In England, the Animal Health and Welfare Review and Endemic Disease Follow-Up provide an opportunity to engage with producers (Defra and Rural Payments Agency, 2025). While primarily focused on bovine viral diarrhoea (BVD), the funded visits and biosecurity review offer a platform for discussing broader calf health topics. On farms where BVD may be endemic, tackling the virus may also reduce the impact of calf diarrhoea.

Colostrum management

Colostrum is key to calf health. Since no transfer of immunoglobulins (IgG) across the bovine placenta takes place, calves rely entirely on colostrum to acquire passive immunity after birth (Lopez and Heinrichs, 2022). Ensuring effective colostrum management is therefore one of the most impactful interventions for improving calf health.

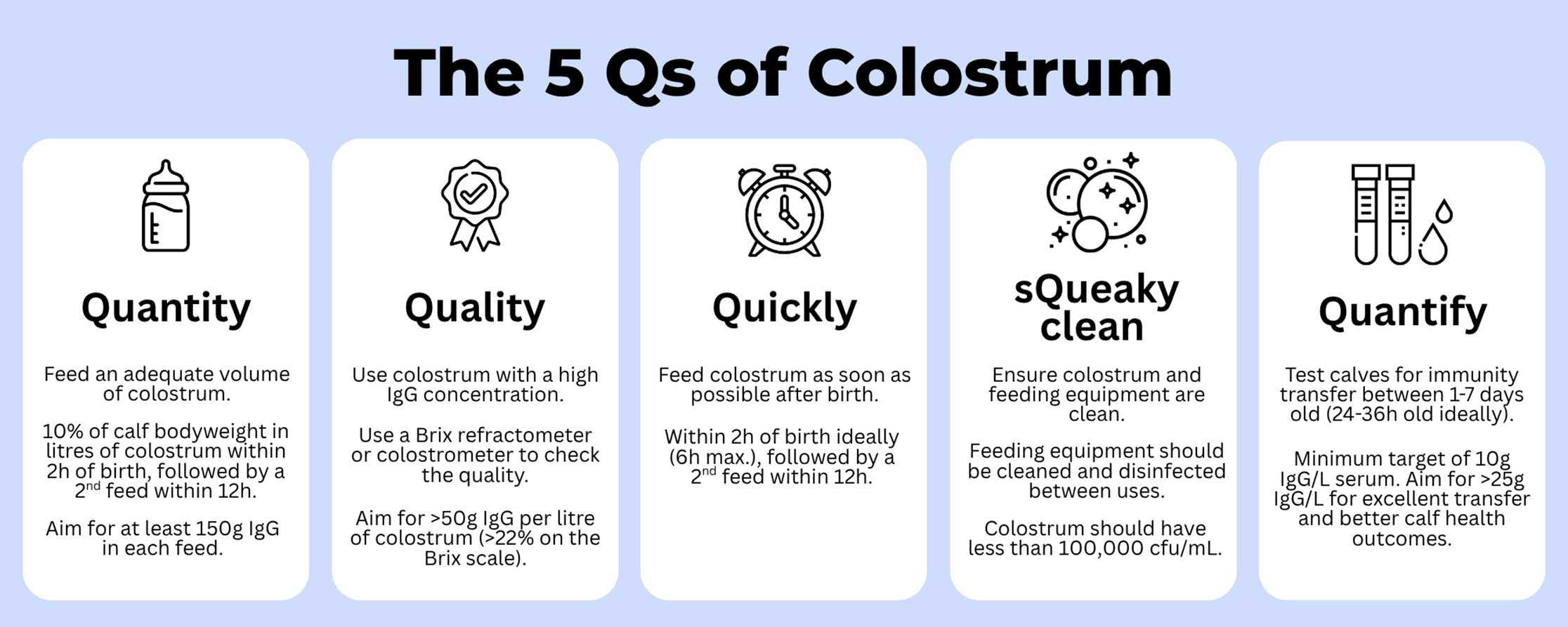

The traditional “three Qs of colostrum” – quantity, quality and quickly – summarise the essential principles of good colostrum management (AHDB, no date, a). In recent years, this concept has been expanded to five Qs, adding squeaky clean and quantify (Figure 2; Geiger, 2020). These highlight the importance of hygiene in colostrum harvesting and feeding, and the value of measuring passive transfer in the calves to assess and improve farm protocols (Geiger, 2020; Denholm et al, 2025).

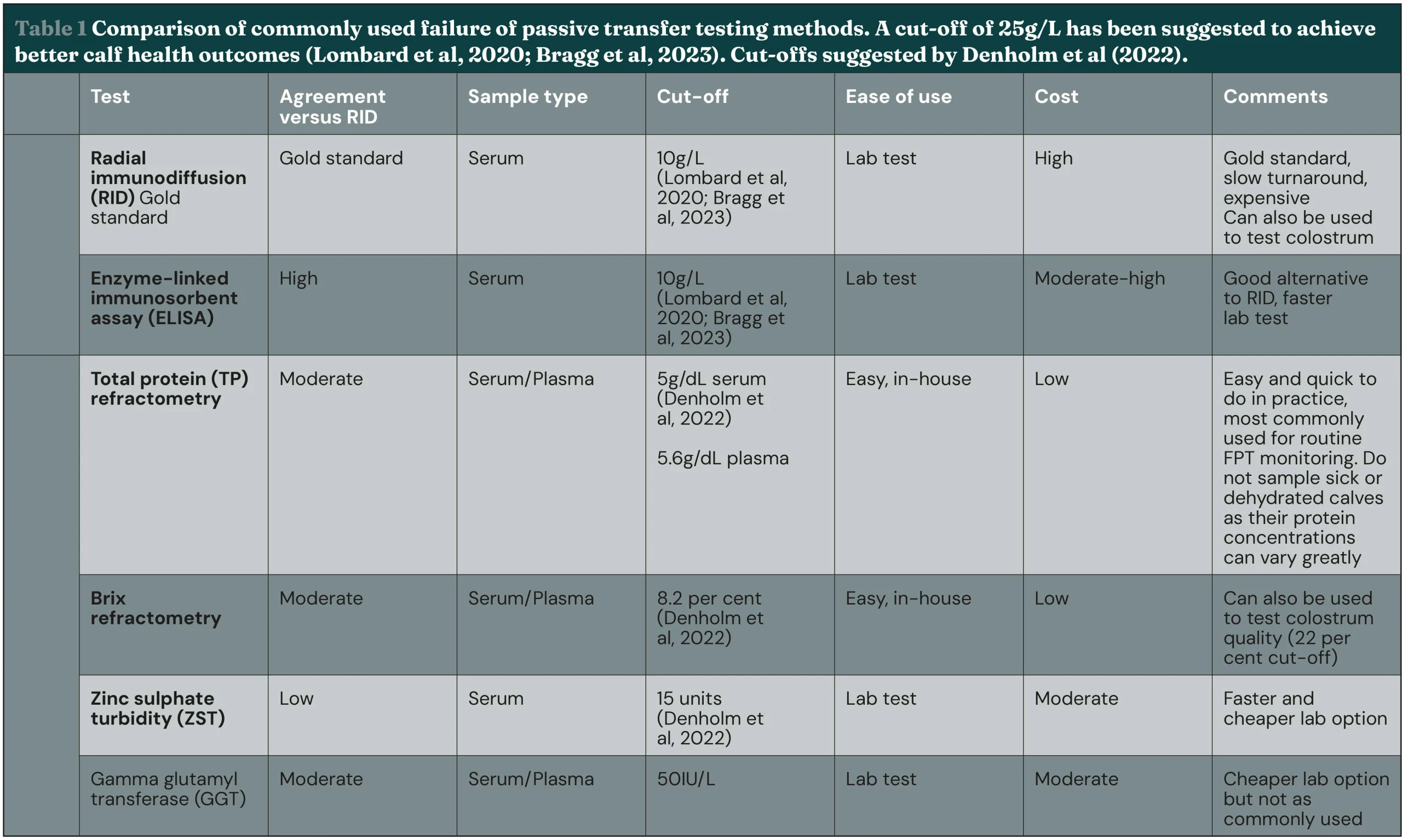

Calves that do not receive enough high-quality colostrum within the critical first six hours of life are at risk of failure of passive transfer (FPT), which increases the risk of disease and is associated with poor growth, and reduced lifetime productivity (Lombard et al, 2020; Boccardo et al, 2021; Lopez and Heinrichs, 2022). Traditionally, FPT has been defined as serum IgG concentrations below 10mg/ml between one and seven days of age (Lopez and Heinrichs, 2022). However, later recommendations suggest aiming higher: calves with more than 25mg/ml IgG in serum are more likely to achieve optimal health and performance outcomes (Lombard et al, 2020; Bragg et al, 2023).

Despite the recognised importance of passive transfer, colostrum quality testing (that is, via Brix refractometry or using a colostrometer) and serum IgG monitoring in the calves (Gladden, 2019; Table 1) are still not routinely implemented on many farms (Baxter-Smith and Simpson, 2020). This represents a key opportunity for improvement, both in dairy and beef herds.

Testing may be harder to carry out in suckler herds, but colostrum quality spot checks could be done each time there is an assisted calving (if safe to take a colostrum sample) and calves could be blood sampled at tagging. Sampling 12 calves per calving group or season should be enough (Cuttance et al, 2019).

In addition to its role in passive immunity, latest research has highlighted the potential extended benefits of colostrum and transition milk beyond feeding beyond the critical first hours of life. In dairy calves, feeding transition milk or supplementing milk with colostrum can support gut health, modulate inflammation and reduce the severity of diarrhoea episodes. This could help boost the animals’ general health and can be used as a non-antibiotic treatment alternative during disease outbreaks (Carter et al, 2021; Denholm et al, 2025). McCarthy et al (2023) found that diarrhoeic calves that were fed three litres of colostrum a day for three days, alongside fluid therapy, had a reduction in diarrhoea duration and antimicrobial use compared to control groups receiving standard milk replacer.

Although more research is needed in this area, these additional uses of colostrum may help mitigate illness and reduce antimicrobial use.

Vaccination

Multiple vaccines are commercially available for the main pathogens associated with calf diarrhoea (Maier et al, 2022). However, uptake in the UK remains relatively low. Baxter-Smith and Simpson (2020) reported that only 29% of surveyed farmers were using a scour vaccine, and national estimates suggest an uptake of just 24%, based on the ratio of total doses sold to the number of breeding-age females (AHDB, no date, b). Improving vaccination uptake, particularly on farms with recurring scour issues, represents an opportunity for disease reduction and improved calf outcomes.

A recent development in this area was the launch of the first vaccine against C parvum in 2024 (MSD Animal Health, 2024). Cryptosporidiosis is the most diagnosed cause of calf diarrhoea in the UK and Ireland (Figure 1). It is also one of the most challenging pathogens to manage, as it is highly infectious, environmentally persistent and resistant to many common disinfectants.

Treatment options are also limited (Adkins, 2022). The new vaccine therefore offers a potentially valuable tool in reducing the impact of cryptosporidiosis on farms where the disease has been identified as a recurring problem.

Nevertheless, vaccination on its own will never resolve a diarrhoea problem. Effective colostrum management, strict hygiene and biosecurity protocols remain critical in any calf health programme.

Vaccines should be viewed as part of a broader prevention strategy: while they can reduce the severity and incidence of disease, their efficacy depends on correct administration, timing and proper colostrum uptake by the calf.

Vaccine efficacy will also vary depending on the pathogens circulating on the farm, so regular disease surveillance and diagnostic testing are important to inform vaccination decisions. As with the new cryptosporidiosis vaccine, further field experience and research will help to define its long-term impact on reducing diarrhoea-related morbidity and mortality.

Conclusion

Calf diarrhoea remains a persistent challenge on UK farms, and research highlights the ongoing need for greater farmer engagement and veterinary involvement in outbreak management.

While the core principles of diarrhoea management have remained consistent, advances in colostrum research and vaccine development offer new tools that may help reduce the disease morbidity, mortality and long-term calf health impacts.

- This article appeared in Vet Times Livestock (Summer 2025; Volume 11, Issue 2, Pages 2-6), available in VT55.29.

- For more calf health topics from the Vet Times clinical archive, visit here.

Author

- Anna Bruguera Sala qualified from the Autonomous University of Barcelona in 2013. After an externship in mixed practice in Ireland, she completed a two-year farm internship at the University of Glasgow’s school of veterinary medicine, combined with a master’s degree in animal health surveillance which focused on bovine viral diarrhoea. Since 2017, Anna has been working as a farm vet at Alnorthumbria Veterinary Group in Northumberland.

References

- Abuelo A, Cullens F and Brester JL (2021). Effect of preweaning disease on the reproductive performance and first-lactation milk production of heifers in a large dairy herd, Journal of Dairy Science 104(6): 7,008-7,017.

- Adkins PRF (2022). Cryptosporidiosis, Veterinary Clinics of North America: Food Animal Practice 38(1): 121-131.

- AHDB (no date, a). #ColostrumIsGold, available at tinyurl.com/y32v38uw

- AHDB (no date, b). Use of vaccines in cattle, available at tinyurl.com/2v75nbfa

- APHA (2023). Veterinary Investigation Diagnosis Analysis (VIDA) Annual Report 2023, available at tinyurl.com/huxrrrue

- Baxter-Smith K and Simpson R (2020). Insights into UK farmers’ attitudes towards cattle youngstock rearing and disease, Livestock 25(6): 274-281.

- Boccardo A, Sala G, Ferrulli V and Pravettoni D (2021). Cut-off values for predictors associated with outcome in dairy calves suffering from neonatal calf diarrhea. A retrospective study of 605 cases, Livestock Science 245: 104407.

- Bragg R, Corbishley A, Lycett S, Burrough E, Russell G and Macrae A (2023). Effect of neonatal immunoglobulin status on the outcomes of spring-born suckler calves, Vet Record 192(6): e2,587.

- Carter HSM, Renaud DL, Steele MA, Fischer-Tlustos AJ and Costa JHC (2021). A narrative review on the unexplored potential of colostrum as a preventative treatment and therapy for diarrhea in neonatal dairy calves, Animals (Basel) 11(8): 2,221.

- Cuttance EL, Regnerus C and Laven RA (2019). A review of diagnostic tests for diagnosing failure of transfer of passive immunity in dairy calves in New Zealand, New Zealand Veterinary Journal 67(6): 277-286.

- DAFM and AFBI (2023). All Island Disease Surveillance Report 2023, available at tinyurl.com/yyvzywwv

- Defra and Rural Payments Agency (2025). Funding to improve animal health and welfare: guidance for farmers and vets, available at tinyurl.com/ykvnkyp6

- Denholm KS, Baxter-Smith K, Haggerty A, Denholm M, Williams P and Vertenten G (2025). Randomized prospective study exploring health and growth outcomes for 5 days of extended transition milk feeding in pre-weaned Scottish replacement dairy heifers, Research in Veterinary Science 188: 105543.

- Heller MC and Chigerwe M (2018). Diagnosis and treatment of infectious enteritis in neonatal and juvenile ruminants, Veterinary Clinics of North America: Food Animal Practice 34(1): 101-117.

- Geiger AJ (2020). Colostrum: back to basics with immunoglobulins, Journal of Animal Science 98(Supp1): S126-S132.

- Gladden N (2019). Measurement of passive transfer of immunity in calves, Vet Times 49(40): 14-15.

- Godden SM, Lombard JE and Woolums AR (2019). Colostrum management for dairy calves, Veterinary Clinics of North America: Food Animal Practice 35(3): 535-556.

- Goh N, House J and Rowe S (2024). Retrospective cohort study investigating the relationship between diarrhea during the preweaning period and subsequent survival, health, and production in dairy cows, Journal of Dairy Science 107(11): 9,752-9,761.

- Gull T (2022). Bacterial causes of intestinal disease in dairy calves: acceptable control measures, Veterinary Clinics of North America: Food Animal Practice 38(1): 107-119.

- Johnson KF, Chancellor N, Burn CC and Wathes DC (2017). Prospective cohort study to assess rates of contagious disease in pre-weaned UK dairy heifers: management practices, passive transfer of immunity and associated calf health, Veterinary Record Open 4(1): e000226.

- Lombard J, Urie N, Garry F, Godden S, Quigley J, Earleywine T, McGuirk S, Moore D, Branan M, Chamorro M, Smith G, Shivley C, Catherman D, Haines D, Heinrichs AJ, James R, Maas J and Sterner K (2020). Consensus recommendations on calf- and herd-level passive immunity in dairy calves in the United States, Journal of Dairy Science 103(8): 7,611-7,624.

- Lopez AJ and Heinrichs AJ (2022). The importance of colostrum in the newborn dairy calf, Journal of Dairy Science 105(4): 2,733-2,749.

- Mahendran SA, Wathes DC, Booth RE and Blackie N (2021). A survey of calf management practices and farmer perceptions of calf housing in UK dairy herds, Journal of Dairy Science 105(1): 409-423.

- Maier GU, Breitenbuecher J, Gomez JP, Samah F, Fausak E and VanNoord M (2022). Vaccination for the prevention of neonatal calf diarrhea in cow-calf operations: a scoping review, Veterinary and Animal Science 15: 100238.

- McCarthy HR, Cantor MC, Lopez AJ, Pineda A, Nagorske M, Renaud DL and Steele MA (2024). Effects of supplementing colostrum beyond the first day of life on growth and health parameters of preweaning Holstein heifers, Journal of Dairy Science 107(5): 3,280-3,291.

- Mee JF (2023). Invited review: bovine neonatal morbidity and mortality – causes, risk factors, incidences, sequelae and prevention, Reproduction in Domestic Animals 58(2): 15-22.

- MSD Animal Health (2024). MSD Animal Health receives VMD approval for Bovilis Cryptium, available at tinyurl.com/3p25vw4n

- Payne E and Gladden N (2024). Communicating calf scour messages to farming clients, Vet Times Livestock 10(1): 12-18.

- Tilling O (2018). Diagnosing and treating calf scour, Vet Times 48(12): 18-20.

- Todd CG, Millman ST, McKnight DR, Duffield TF and Leslie KE (2010). Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug therapy for neonatal calf diarrhea complex: effects on calf performance, Journal of Animal Science 88(6): 2,019-2,028.

- Welk WA, Cantor MC, Neave HW, Costa JHC, Morrison JL, Winder CB and Renaud DL (2025). Effect of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs on neonatal calf diarrhea when administered at a disease alert generated by automated milk feeders, Journal of Dairy Science 108(2): 1,842-1,854.