20 Aug 2024

Latest on pet worming protocols and treatments

Ian Wright BVMS, BSc, MSc, MRCVS takes a look at the potentially looming threat of exotic parasites in cats and dogs in the UK.

Image: Tatyana Gladskih/ Adobe Stock

Routine deworming remains a fundamental component of preventive health programmes for UK cats and dogs. The aim of these treatments is both to improve the health of pets and to reduce zoonotic risk.

The worms infecting UK cats and dogs that are of most concern when considering these factors are Angiostrongylus vasorum in dogs, due to its potential to cause significant disease, and Toxocara species and Echinococcus granulosus, both due to their zoonotic potential. For each one, a lifestyle and geographic risk assessment should be made before deciding on whether routine deworming is required and at what frequency.

Toxocara species

Puppies and kittens provide the largest source of potential infection. Treatment of puppies should start at two weeks of age, repeated at two-weekly intervals until two weeks post-weaning and then monthly until six months old.

Kittens should be treated in the same way, with the first treatment being given at three weeks old as no trans-placental transmission occurs. Adult cats and dogs have potential to shed zoonotic eggs throughout their lives, so the aim of regular deworming is to keep adult worm populations down and reduce egg shedding. The European Scientific Counsel Companion Animal Parasites (ESCCAP) recommends deworming adult cats and dogs every three months for this purpose, increasing to monthly in high-risk groups to reduce shedding further. High-risk cats and dogs include those hunting, in contact with young children or immune-suppressed individuals, and those on raw diets that have not been adequately pre-frozen (-20°C for at least seven days).

Indoor cats do not require routine deworming, as their chances of infection with subsequent shedding will be lower, and ova do not have the opportunity to mature if litter trays are cleaned out regularly and faeces disposed of responsibly. Routine faecal testing at least four times a year can be used as an alternative to routine deworming for Toxocara species, as long as the pet owner understands that egg shedding may go undetected in between tests with potential zoonotic consequences. Testing should be performed at least once a year alongside treatment to demonstrate adequate deworming frequency, efficacy and compliance.

Echinococcus granulosus

E granulosus is a severe zoonosis with immediately infective eggs passed in the faeces of infected dogs. Dogs at high geographic or lifestyle risk should be treated with praziquantel monthly to minimise egg shedding. Known endemic foci of E granulosus endemic foci include Herefordshire, mid-Wales (particularly Powys) and the western isles of Scotland. Dogs living in these areas with off-lead access should be treated monthly.

Surveys of both abattoirs and copro-antigen studies of farm and hunting dogs in Britain suggest endemic foci exist in other parts of the country. The location of these is uncertain, so prevention measures should be put in place for any dog whose lifestyle puts it at risk. These include dogs with access to raw offal or fallen livestock carcases, as well as those on raw diets that have not been adequately pre-frozen (-18°C for at least seven days).

Angiostrongylus vasorum

A vasorum is present in fox populations across the UK, with resultant domestic dog exposure through the consumption of mollusc intermediate hosts or paratenic hosts such as frogs (Taylor et al, 2015). Its distribution, however, is not uniform, with focal areas of very high prevalence and other areas remaining free of infection.

Case reporting sites have been useful in mapping areas of high prevalence, but reporting is only voluntary and presence of the parasite very fluid. In areas known to be endemic for foci, monthly preventive treatment with a licensed macrocyclic lactone should be routine. In areas where endemic status is not certain, testing dogs prior to surgery and those with relevant clinical signs (unexplained cough or bleeding) will build up a picture of whether A vasorum is present locally, and whether monthly deworming for the parasite is indicated.

Dogs at high risk due to lifestyle factors should also be treated monthly. These include dogs that deliberately eat slugs and those that may accidentally ingest them though consumption of grass and faeces.

This deworming status quo may change as more data on parasite distributions and relative risk becomes available. The factor most likely to change deworming protocols in the near future, however, is the introduction of exotic worm species to UK cats and dogs that are of pathogenic and zoonotic concern.

Exotic worms and how deworming protocols may change with their arrival

Legal and illegal importation of dogs are increasing the risk of exotic worms entering the UK and becoming established. Exotic worms are being seen in travelled UK cats and dogs with increasing regularity, and veterinary professionals need to be aware of these foreign travellers for both individual pet health and national biosecurity. Four exotic parasitic worms will affect routine deworming of pets if they establish in this country.

Heartworm (Dirofilaria immitis)

Dirofilaria immitis is a filarial heartworm primarily of dogs, but also it can infect ferrets and felines. It is a significant cause of heart disease and of bronchitis in cats.

Transmission occurs via the bites of infected mosquitoes. Infections may remain subclinical for months or years before potentially severe signs develop associated with chronic heart changes, adult worm death, thromboembolism, and inflammatory responses associated with larval worm migration.

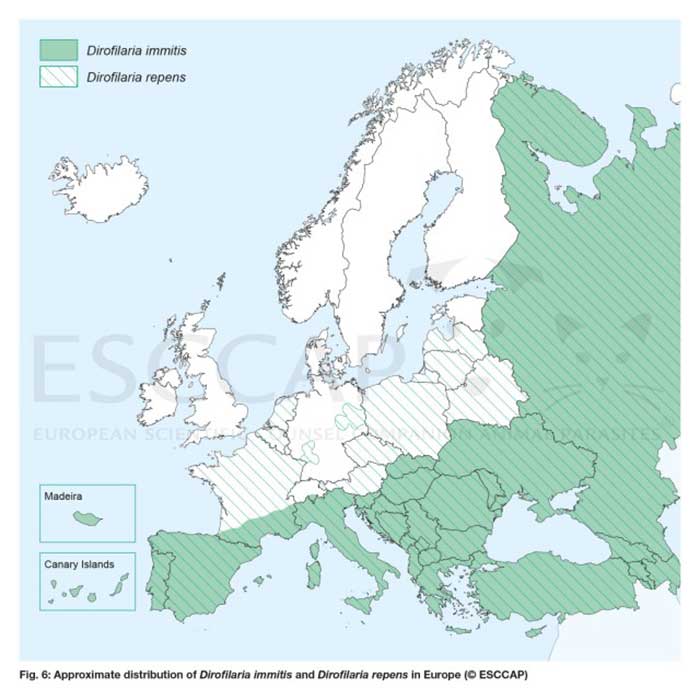

The parasite is present in parts of Africa, Asia, North America and South America. In Europe, it has been limited to southern Europe, but now is spreading north through eastern Europe (Figure 1). Mosquitoes capable of transmitting D immitis can be found throughout the whole of Europe, including the UK, but the climate in northern and central Europe has been too cold to allow D immitis to complete its life cycle in the mosquito year on year. Climate change, in combination with increased movement of pets, is allowing the parasite to spread.

A paper this year highlighted cases in untravelled dogs from Estonia, the furthest north in Europe that they have been reported (Mõttus et al, 2024). It is likely that endemic foci will establish in the UK in the next few years. Cats and dogs living in endemic countries require monthly licensed macrocyclic lactones to prevent infection, and if the parasite does establish in the UK, this will be required in endemic regions.

Rapid diagnosis in imported pets is important to manage infection, and preventive treatment for pets travelling to endemic countries is vital to keep pets safe.

As temperatures warm, these measures will become increasingly important to keep D immitis from establishing in the UK. Diagnostic tests available for screening pets entering the UK include:

- Examination of blood for microfilaria. Concentration techniques, such as the Knott’s test, are more sensitive than direct whole blood examination in canine patients, but still extremely insensitive in the cat due to microfilariae being absent or present in low numbers.

- Radiology. Thoracic radiographic changes are not pathognomonic, but are important to assess cardiac changes for prognostic purposes. Diffuse interstitial patterns, right-sided heart enlargement and enlargement of the pulmonary arteries – particularly the caudal lobar arteries – may all be present.

- Ultrasound examination. The cuticles of adult heartworms are highly echogenic, and so in experienced hands, echocardiography is very sensitive and specific. The pulmonary artery needs to be traced to its first bifurcation to ensure no adult heartworms are missed.

- Antigen serology. This test is considered the gold standard in the living canine patient. It is highly specific and also highly sensitive in canine patients. Although still highly specific in cats, it is much less sensitive due to adult heartworms being present in very small numbers or absent.

- Antibody serology. This is the most sensitive blood test available for heartworm diagnosis in cats. A positive result may indicate past or present exposure to infection, and should be interpreted in relation to clinical signs and other diagnostic tests.

Treatment of infections with adult worms requires surgical removal or medical treatment with an adulticide. Intravascular snares and forceps are often used in endemic countries to remove large numbers of worms in the least invasive manner. These techniques require experience and specialised equipment, however, and as a result, most UK cases will be treated medically.

Treatment protocols in dogs vary and fall into one of two strategies: use of an adulticide (melarsomine) or macrocyclic lactones without an adulticide (“slow kill” methods). An example of a typical adulticide treatment programme is:

- Day 1: doxycycline 10mg/kg orally once daily for 30 days.

- Heartworm preventive (macrocyclic lactone on day 0 and 30).

- Day 30: melarsomine dihydrochloride 2.5mg/kg intramuscularly (IM).

- Day 60 and 61: melarsomine dihydrochloride 2.5mg/kg IM.

The patient should then be tested for microfilariae 30 days post-treatment and antigen serology tested six months post-treatment. The use of doxycycline is to kill Wolbachia species bacterial infection residing within the heartworms.

The worms and bacteria have an obligatory symbiotic relationship, and treatment of the Wolbachia with doxycycline renders the worms more susceptible to treatment (Kramer et al, 2011).

Growing evidence suggests that waiting a month after doxycycline treatment before adulticide is beneficial in eliminating adult worms. If this is to be incorporated into a treatment protocol then adulticides would be administered at days 60, 90 and 91. Prednisone has some benefit in reducing the risk of thromboembolic complications if given alongside adulticide treatment where worm burdens are high (Dzimianski et al, 2010). If high worm burdens are suspected, oral prednisolone can be used from the initiation of adulticide treatment at 0.5mg/kg twice a day for one week and 0.5mg/kg once daily for the second week, followed by 0.5mg/kg every other day for two weeks. These doses are also useful in managing bronchitic signs.

No evidence exists to suggest that aspirin has any protective effect against thromboembolism in heartworm cases during treatment.

The three most significant prognostic factors following adulticide treatment are the severity of existing pulmonary vascular disease, the number of worms present and level of exercise. Of these three, exercise is thought to be the most significant. Exercise should, therefore, be restricted during treatment, starting from day zero to at least one month after the last adulticide injection. The highest risk period of complications from pulmonary thromboembolism is 7 to 10 days after adulticide treatment, but can occur up to 4 weeks after adulticide treatment is completed.

Alternatives that avoid the use of melarsomine are “slow kill” regimes. This should not be as a first-choice treatment in endemic countries, as it has been linked to the development of resistance (Bowman et al, 2012).

It is a viable alternative to adulticide protocols, though, if melarsomine is unavailable or unaffordable. Doxycycline is still used for the first 30 days alongside a monthly macrocyclic lactone (typically moxidectin).

Monthly macrocyclic lactones are given until two consecutive negative antigen tests are achieved. This is typically after at least six months, but can take longer than a year. Exercise restriction is still essential until infection is eliminated.

Dirofilaria repens

Dirofilaria repens is a closely related parasite to D immitis, but is less pathogenic to cats and dogs, with adult worms living in the skin. It has zoonotic potential with the potential to cause creeping eruptions and conjunctivitis in people. It can complete its life cycle at lower temperatures than D immitis (Morgan, 2016) and, as a result, has a far wider distribution across Europe (Figure 1). Cases in travelled dogs in the UK have already been reported (Wright, 2017; Agapito et al, 2017).

If infected dogs continue to enter the UK and are not treated quickly, the possibility exists for UK mosquito populations to be exposed to the parasite and for the disease to become endemic.

If this occurs, it may be desirable to treat cats and dogs routinely with macrocyclic lactones to prevent infection. This would be less important than for heartworm infection, however, as signs in cats and dogs tend to be less severe and zoonotic risk comes from mosquito vectors.

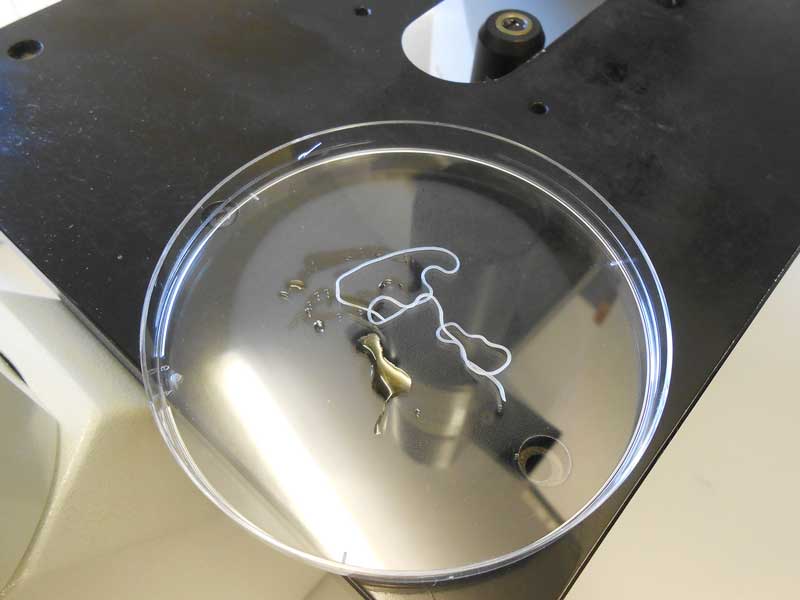

Imported dogs should be checked for ocular and skin lesions, and diagnosis confirmed by Knott’s test for microfilariae, biopsy or identification of aberrant adult worms (Figure 2). These are long and thin without any grossly obvious identifying features. Males are about 5cm to 7cm and females 10cm to 17cm in length. A preventive licensed monthly macrocyclic lactone should be considered for pets travelling to endemic countries.

Discrete subcutaneous nodules containing adult worms can be removed surgically with an excellent prognosis.

Moxidectin/imidacloprid spot-on preparations are licensed for medical treatment, and many infections and their associated clinical signs will resolve with medication alone.

Thelazia callipaeda

Thelazia callipaeda is a zoonotic vector-borne nematode that resides in the conjunctival sac of definitive hosts such as carnivores, rabbits and humans. The worm has been spreading through Europe in recent years, following its fruit fly vector, Phortica variegata. The fly transmits the parasite when feeding on lacrimal secretions. Although often non-pathogenic, infection if left undetected can lead to conjunctivitis, keratitis, epiphora, eyelid oedema, corneal ulceration and, in serious cases, blindness.

Cases in UK travelled dogs were recently recorded in dogs imported from Romania, Italy and France (Graham-Brown et al, 2017). P variegata has been recorded in the UK with conditions favourable for spread and, if exposed to infected dogs, could lead to endemic establishment. It is vital, therefore, that infections are detected rapidly in travelled dogs and treated both for individual case outcomes and to prevent zoonotic risk from infected fruit flies.

No licensed product exists for T callipaeda prevention in cats and dogs, but if the parasite becomes endemic in the UK, with high transmission rates in endemic foci, then macrocyclic lactones may be used off licence for prevention. This will be especially likely if zoonotic cases start to climb. Diagnosis can be achieved by visualisation of the worms on the conjunctiva of the eye. Sedation may be required to fully visualise the worms. Treatment is a combination of eye flushing, physical removal of worms and treatment with a licensed macrocyclic lactone (imidacloprid/moxidectin spot-on treatment or two milbemycin oxime oral treatments given two weeks apart). The APHA, in collaboration with ESCCAP UK and Ireland, is offering free-of-charge morphological identification of suspected cases of T callipaeda, D repens and Linguatula serrata seen in veterinary practices in England and Wales (bit.ly/3M3oNkb).

Submitting samples will confirm diagnosis and also contribute to national surveillance data.

Echinococcus multilocularis

Echinococcus multilocularis is a severe zoonosis, with the adult tapeworm carried by both foxes and domestic canids. Foxes act as a reservoir of infection and rodents, such as microtine voles, as intermediate hosts. Dogs and foxes become infected by predation of the intermediate host, with infection in dogs bringing the parasite into close proximity to people. Cats can act as definitive hosts for E multilocularis, but have a lower worm burden with lower fecundity than canids.

Zoonotic infection occurs through ingestion of eggs passed in the faeces of dogs and foxes which are immediately infective. This can occur though association with infected dogs, through contamination of public spaces by dog fouling or through eating contaminated fruit and vegetables intended for raw consumption. Zoonotic infection results in local and metastatic spread of cysts, leading to hepatopathy and potential multiple organ involvement. Although E multilocularis is not endemic in the UK, the increase in pet travel and importation, alongside the relaxation of the time period allowed between tapeworm treatment and return to the UK, potentially threatens this status.

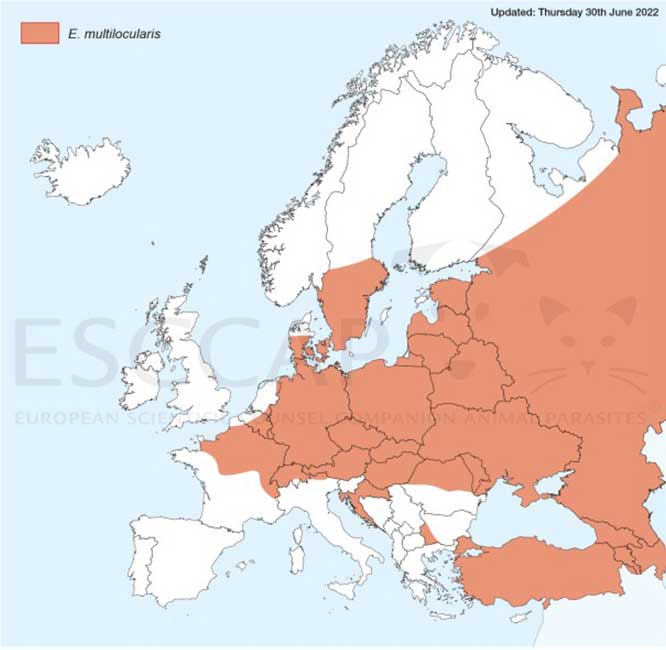

The control of rabies in western and central Europe and subsequent burgeoning fox populations has led to E multilocularis being widespread in Europe (Figure 3). The compulsory treatment still in place before the UK entry scheme still requires dogs to be treated with praziquantel between one and five days before entry to the UK.

This simple treatment has prevented endemic foci from developing and remains vital. The increased treatment window, though, allows the opportunity for infection to occur post-treatment before UK entry.

If E multilocularis is allowed entry into the UK, the large fox and microtine vole population will make widespread endemic establishment likely. In this situation, routine monthly preventive treatment with praziquantel would be required for all dogs with any off-lead outdoor access.

To try to prevent establishment, all travelled dogs should receive an additional praziquantel treatment within 30 days after entry into the UK. For individual pet owner safety, dogs should also receive monthly praziquantel treatment while abroad to minimise the risk of egg shedding of dogs exposed to infection.

Conclusion

Increased movement of pets and fluid vector and parasite distributions in Europe make establishment of exotic parasitic worms in the UK more likely. Exotic parasitic worms should be considered as possible infections in imported and inadequately protected travelled pets.

As well as considering routine deworming for endemic worms, vets and nurses will need to update parasitic control protocols if new parasites become established in the UK. Prevention though early detection and strategic use of parasiticides, however, are the best tools we have to prevent this from occurring.

Use of some of the drugs mentioned in this article is under the veterinary medicine cascade.

- Appeared in Vet Times (2024), Volume 54, Issue 34, Pages 6-14

References

- Agapito D, Aziz N-AA, Wang T, Morgan ER and Wright I (2017). Subconjunctival Dirofilaria repens infection in a dog resident in the UK, Journal of Small Animal Practice 59(1): 50-52.

- Bowman DD (2012). Heartworms, macrocyclic lactones, and the spectre of resistance to prevention in the United States, Parasites and Vectors 5: 138

- Dzimianski MT, McCall JW and Mansour AM (2010). The effect of prednisone on the efficacy of melarsomine dihydrochloride against adult Dirofilaria immitis in experimentally infected beagles. In State of the Heartworm ‘10 Symposium, Memphis, US, American Heartworm Society.

- Graham-Brown J, Gilmore P, Colella V et al (2017). Three cases of imported eyeworm infection in dogs: a new threat for the United Kingdom, Veterinary Record 181(13): 346.

- Kramer L, Grandi G, Passeri B et al (2011). Evaluation of lung pathology in Dirofilaria immitis – experimentally infected dogs treated with doxycycline or a combination of doxycycline and ivermectin before administration of melarsomine dihydrochloride, Veterinary Parasitology 176(4): 357-360.

- Morgan ER (2016). Risks from emerging parasitic zoonoses in companion animals, Companion Animal 21(4): 218-223.

- Mõttus M, Mõtsküla PF and Jokelainen P (2024). Heartworm disease in domestic dogs in Estonia: indication of local circulation of the zoonotic parasite Dirofilaria immitis farther north than previously reported, Parasites and Vectors 17(1): 124.

- Taylor CS, Garcia Gato R, Learmount J et al (2015). Increased prevalence and geographic spread of the cardiopulmonary nematode Angiostrongylus vasorum in fox populations in Great Britain, Parasitology 142(9): 1,190-1,195.

- Wright I (2017). Case report: Dirofilaria repens in a canine castrate incision, Companion Animal 22(6): 316-318.