19 Aug 2025

Mike Davies BVetMed, CertVR, CertSAO, FRCVS considers how vets and their teams can help clients take care of their older dogs and manage their conditions

Older pets are generally well-loved and their owners will welcome the opportunity to assess and improve their health, but veterinary professionals need to be proactive in offering the service.

To optimise the chances for good health and longevity, dog owners need to understand the key issues involved and avoid risk factors for disease. Prevention of age-related diseases is a major objective, as are strategies to delay progression, and these can best be achieved by owners working closely with their veterinary practice.

Signs of ageing and age-related disease become evident from about seven years of age but, of course, wide differences exist in onset and rate of ageing between different breeds, with smaller dogs living considerably longer than large and giant breed dogs, as well as significant differences between individuals of the same breed.

Public and veterinary interest is growing in identifying an animal’s biological age compared to its chronological age, and several companies have launched screening tests to advise owners about their pets’ status.

Associations between high levels of inflammatory cytokines, such as interleukin-6 (IL-6), tumour necrosis factor-α (TNF-α), or the acute phase C-reactive protein (CRP), and a range of adverse ageing outcomes including accelerated vascular ageing, atherosclerosis, bone and muscle loss, and cognitive impairment have been observed in humans (Michaud et al, 2013). CRP measurement in dogs is available and may be a useful tool to assess inflammation in relation to longevity in elderly dogs (Malin and Witkowska-Piłaszewicz, 2022; Oberholtzer and Cook, 2023). However, further work is needed to establish the true value of these biomarkers.

Similarly, measuring DNA methylation in dog blood or saliva has become a popular test with some owners, because evidence exists that this biomarker is related to age in dogs (Jin et al, 2024; Nakamura et al, 2024); it is associated with some diseases and may indicate general health status. Furthermore, obesity is associated with accelerated DNA methylation change in the peripheral blood of senior dogs (Yamazaki et al, 2021). However, the true value of this testing has yet to be confirmed.

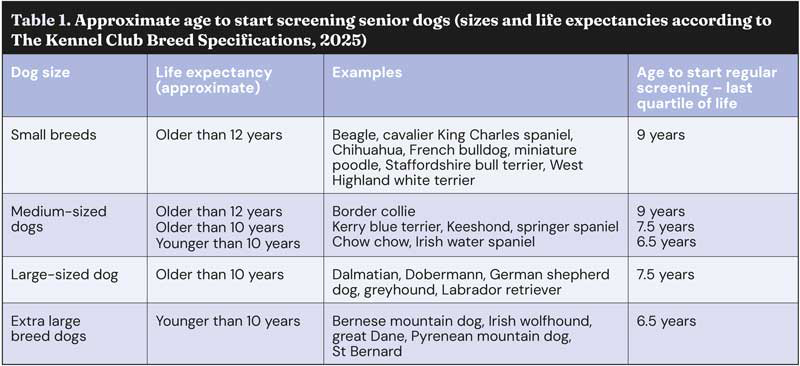

Rather than using an age of, say, seven years to start screening animals as geriatrics, it is better to use the animal’s expected lifespan. Age-related issues are more prevalent in the last quartile of life expectancy, and so that is a good time to start regular screening (Table 1). Most breeds have life expectancies according to size, but some variability exists. For specific breeds, check with the Kennel Club website.

Undoubtedly, the most important thing an owner can do to ensure their dog has a long and healthy life is to maintain a healthy body condition score (BCS) of 4/9 to 5/9 on a 9-point scale (see the WSAVA BCS chart).

In a lifetime study of 48 Labrador retrievers (Kealy et al, 2002; Lawler et al, 2008), dogs fed 25 per cent less food than their littermates lived on average 18 months longer and the onset of common age-related diseases was delayed by two years. None of the dogs in the group fed 25 per cent less food developed clinical signs of hip OA and the earliest radiographic signs occurred six years later (at nine years of age) than in the control group.

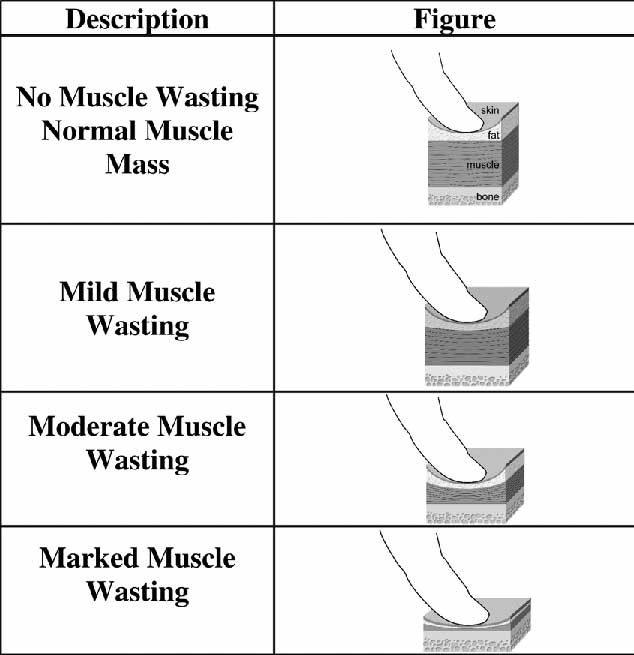

Among all dogs, high static fat mass and declining lean body mass predicted death, most strongly at one year prior, while fat mass more than 25 per cent was associated with chronic diseases (Lawler et al, 2008). Assessment of BCS and muscle mass using a muscle score (Figure 1) are useful and, if available, ultrasound or DEXA scanning might be viable diagnostic tools for more accurate evaluation of muscle mass.

It should be noted that in older animals, muscle may be replaced by fat, and so an apparently normal muscle mass on palpation alone may be a false assumption.

The results of one study in dogs suggest that preventing the development of overweightness and obesity reduces the prevalence of hip dysplasia and OA of the hip and other joints.

Three other studies support weight loss as an effective treatment for OA in affected overweight and obese dogs (Mlacnik et al, 2006; Marshall et al, 2009).

Regular exercise is important to maintain muscle and skeletal bone and cartilage composition, health and function. It also helps control bodyweight and adipose tissue deposition, as well as stimulating endorphin release, adding to well-being. For animals with impaired exercise capability, just 20 minutes walking a day can be helpful, and group walks for owners with senior dogs have been shown to be beneficial.

However, in dogs with OA, some evidence exists that moderate exercise could have a detrimental effect, as measured by force plate analysis (Beraud et al, 2010). Swimming and/or physiotherapy are good alternates to walking and help maintain joint movement and flexibility.

Physiotherapy is one of the services that a practice could include in its geriatric programme.

Regular vaccination and parasite control in accordance with manufacturer’s instructions is important, as elderly animals have reduced immune-response capability (HogenEsch et al, 2004; Lawler et al, 2008; Greeley et al, 1996; Strasser et al, 2000) and are, therefore, most susceptible to succumb to serious infectious agents or parasites.

Concerns about risks associated with canine vaccination are ill-founded (Moore et al, 2005); however, concerns about over-treatment for parasites need to be fully assessed by the practice to avoid unnecessary medication and environmental contamination.

In recent years, concerns have been expressed regarding possible side effects of neutering, including possible increased risk of neoplasia, musculoskeletal and endocrinological conditions. In some breeds, neutering has been shown to reduce lifespan (Joonè and Konovalov, 2023). In this study, male and female Rottweilers neutered before one year of age (n=207) demonstrated an expected lifespan one and a half years and one year shorter, respectively, than their intact counterparts (n=3085; p<0.05). Broadening this analysis to include animals neutered before the age of four and a half years (n=357) produced similar results.

The risks versus benefits of neutering were discussed at BVA Live in June 2025, but this aspect was not mentioned during the proceedings. Perhaps we should not be neutering breeds in which reduced longevity is documented, unless the benefits are clearly demonstrated. For potential benefits of neutering, such as reduced risk of cancer (prostate/mammary) or behaviour management, the evidence is regarded as weak and other side effects exist, such as urinary incontinence, post-surgical hernia, and anaesthetic risks to consider.

Although a lot of pet foods marketed for senior dogs exist, almost none of them have any feeding trial evidence to support their use. In addition, the vast majority of pet foods sold in the UK as complete do not comply with FEDIAF Nutritional Guidelines (Davies et al, 2017).

FEDIAF (2024) does not state different nutritional requirements for older dogs compared to healthy adults, and although some plausible reasons exist to vary ingredients (for example, to reduce phosphorus content), these modifications have not been shown to be beneficial, except for clinical trials of veterinary therapeutic diets intended for use in specific clinical situations.

For apparently healthy dogs, the author advises owners to feed a pet food made to a fixed formula, and that the manufacturers analyse after every batch to ensure compliance with FEDIAF. For animals with age-related disease, the author advises feeding an appropriate therapeutic diet with proven efficacy.

The author discourages owners from feeding raw foods, as older dogs are more susceptible to food borne infections (Davies et al, 2019), and advises against homemade rations because of the difficulty of formulating a complete and balanced ration (Davies, 2014). Owners should be advised not to give too many treats and supplements, as these are not needed, provide unnecessary calories and can alter the overall completeness and balance of the ration. It is necessary to conduct a thorough nutritional history and assessment (visit www.wsava.org) to identify cases requiring nutritional support.

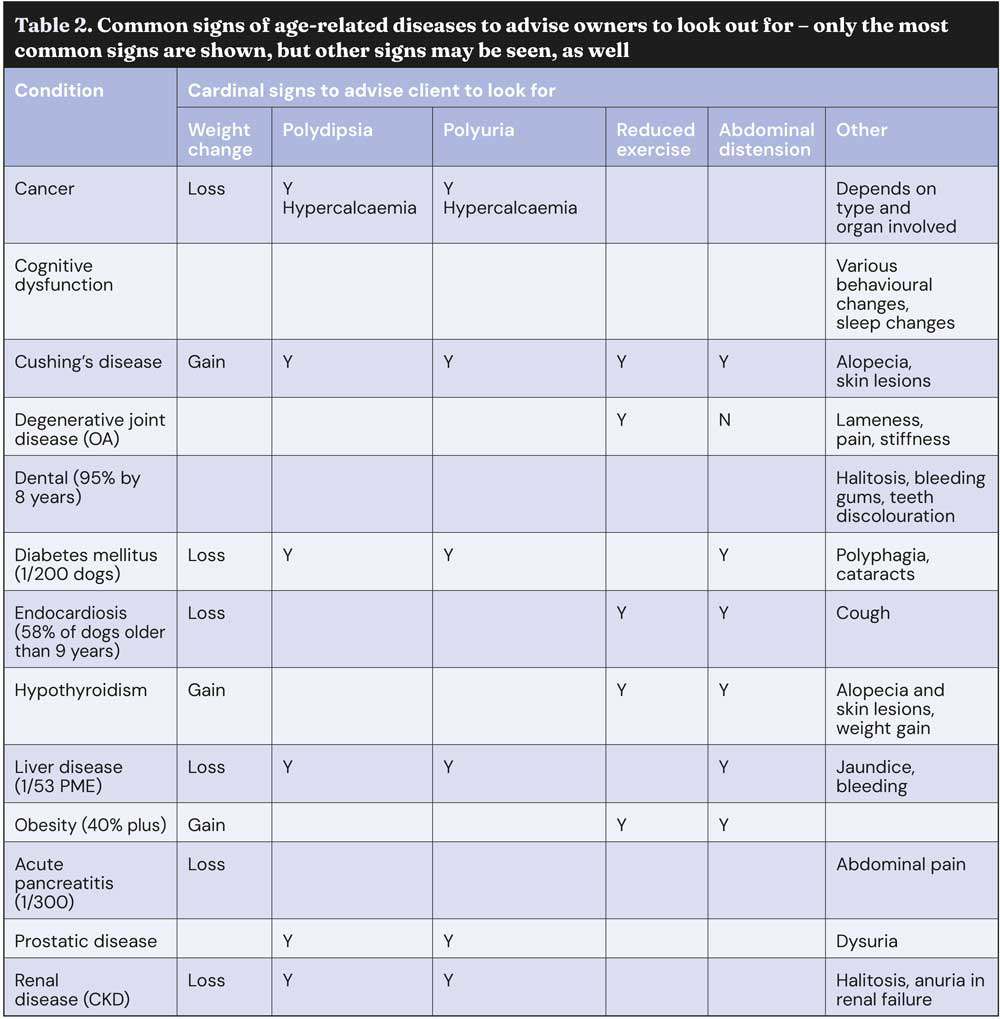

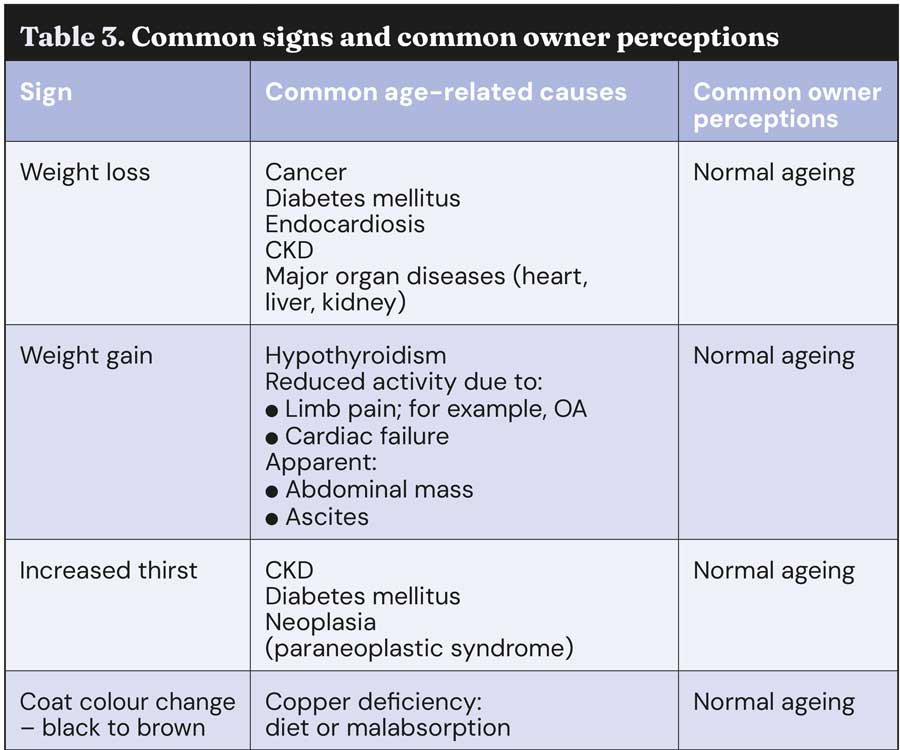

Ageing in dogs is inevitable and progressive, and the occurrence of age-related diseases becomes increasingly likely as an animal gets older (Table 2). Owners know this, but generally they do not recognise signs of common diseases (Table 3) or realise when to take veterinary advice.

In an online survey of 557 pet owners, more than one-quarter of respondents thought the cardinal signs of weight loss, increased thirst, loss of appetite, hindleg stiffness, obesity, reduced exercise and halitosis were not important enough to warrant a trip to their vets, and 15 per cent did not consider haematuria important enough, either (Davies, unpublished Provet survey). This highlights the need to educate our clients about what to look out for as their pet ages. The author prefers to give written as well as verbal advice, and these days practices are increasingly using websites and social media to communicate with their clients – this allows for regular ongoing communication and feedback for monitoring progress.

External signs of ageing can include changes (greying) in hair-coat colour, behavioural changes such as loss of cognitive performance, physical changes such as posture and mobility, and lens opacity due to nuclear sclerosis. However, similar signs can be associated with disease; for example, black dogs turning brown usually indicates copper deficiency (Figure 2), and lens opacity can be due to cataracts secondary to diabetes mellitus (Figure 3).

Ageing changes occur in all tissues to some degree or other and they may reduce tissue reserve impairing the ability to respond to stress, but they do not cause disease and clinical signs. Age-related diseases, on the other hand, are often insidious in onset, present as subclinical disease, are progressive and may result in organ failure.

The most important steps that a veterinary practice can do are:

The aims of a geriatric screen are to:

A geriatric screen should consist of a full detailed history and physical examination which, for the author, includes bodyweight measurement; BCS assessment; ophthalmoscopy; oral examination, including teeth and mucous membranes for colour and capillary refill time; chest auscultation, abdominal palpation; muscle scoring; limb palpation and joint manipulation; blood pressure measurement; and neurological testing. In males, a rectal examination for prostate enlargement is performed. This means that a veterinary nurse cannot do a full geriatric screen.

Using this protocol, on average, the author finds more than seven clinical findings per dog (Davies, 2012), many of which require further diagnostic investigations or medical or surgical intervention.

The author performs routine urinalysis (dip stick and measure specific gravity by refractometer), but only does a blood screening test if this is indicated from the history or examination.

The exception for performing routine blood screening is if an elderly dog is scheduled for general anaesthesia; in the author’s study (Davies and Kawaguchi, 2014) involving a total of 7,039 test results from 474 dogs (mean age 9.64 years), 5,730 (81.4 per cent) were within the reference range. In all, 102 dogs (21.51 per cent) did not proceed to general anaesthesia for a variety of reasons, and in 39 (8.23 per cent), the clinician recorded concern about the blood test results. The general anaesthetic protocol was documented to have been changed due to abnormal blood tests for 19 (4 per cent) of dogs.

The Frailty Index, based on clinical data, has been validated for use in dogs (Banzato et al, 2019) and this can be used to determine mortality risk in individual dogs. Patients with a high Frailty Index (FI; >0.25) should be treated with particular care and may need more frequent follow-up visits than subjects with a low FI.

Over the years, fewer and fewer practices seem to be running geriatric programmes, which is a disappointment because of the documented benefits they have for the large elderly population of animals in a practice (Davies, 2014), to their owners (who are increasingly expecting the same standards of care as their elderly relatives get) and also for the practice, which can manage patients better with early diagnoses. Veterinary nurses can run a lot of the components of a geriatric programme, but veterinary staff need to be involved in the physical examination and clinical decision-making process.

Owner compliance with veterinary recommendations is often a problem and that is why joint collaboration is needed when running a geriatric programme.

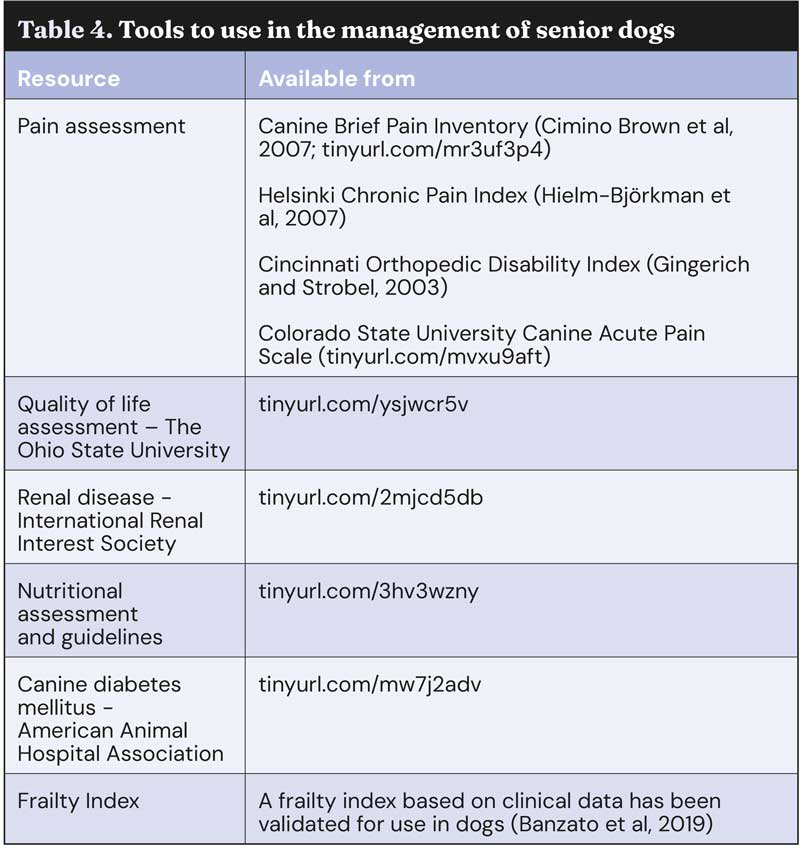

Whenever possible, follow disease management protocols developed by expert committees; for example the International Renal Interest Society guidelines for renal disease and American Animal Hospital Association guidelines for diabetes mellitus. Monitoring pain is an important activity, as many dogs on analgesics may in fact still be in pain (Davies, 2012). See Table 4 for other useful tools. With possible declining renal and/or hepatic function, medications should be selected carefully for use in senior dogs; those that are contraindicated in their SPC should be avoided.

Whenever possible, avoid polytherapy, and if drug combinations are needed, ensure evidence of safety in elderly dogs. The author never prescribes human drugs and only use POM-V licensed products in senior animals, especially avoiding unlicensed drugs such as oral paracetamol, which has been shown to cause liver damage even at low doses being used to avoid acute toxicity.

Veterinary practices and owners can work together to manage senior dogs optimally by ensuring regular weighing, BCS and muscle assessments and feeding a complete balanced ration throughout life, to maintain a BCS of 4/9 to 5/9. Ensure regular exercise, vaccinations and parasite control.

Practices can provide individualised educational materials about clinical signs to look for that relate to the common diseases owners are likely to see in their ageing dog.

Practices should enrol clients into regular screening; ideally run a formal geriatric programme; use surgical or medical interventions as early as possible, but avoid polypharmacy; and monitor the ongoing effectiveness and safety of medical interventions. Regular, clear communication with clients is essential.

Mike Davies qualified from the RVC, has RCVS postgraduate certificates in veterinary radiology and small animal orthopaedics, and holds a fellowship by examination in clinical nutrition in cats and dogs. He is an RCVS specialist in veterinary nutrition (small animal clinical nutrition). Mike has worked in academia and private practice, and for several pet food manufacturers and pharmaceutical companies. He speaks internationally on clinical nutrition and geriatrics, and founded the original City and Guilds certificate in small animal nutrition, and the BVNA certificates in small animal and exotic nutrition. He runs Provet’s certificate course in clinical nutrition.