1 Mar 2022

Acute pancreatitis – diagnosis, management and communication

Kit Sturgess details the signs, treatments and best course of discussion with owners for this condition in both cats and dogs.

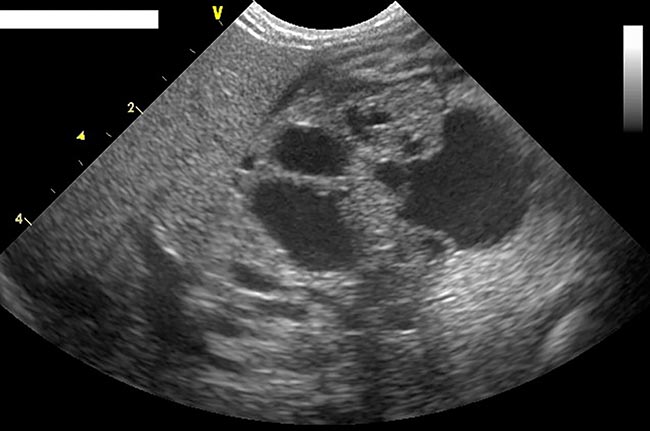

Figure 2b. A seven-year-old, female, neutered border terrier presenting with 48-hour history of inappetence and vomiting progressing to abdominal swelling and jaundice. Diagnosis of acute, sterile pancreatitis with ascites and partial biliary obstruction.

Acute pancreatitis is a potentially severe and life-threatening condition in cats and dogs, although it is important to not equate acuteness to severity.

Severe acute pancreatitis in man is associated with a mortality rate of 10% to 85% (Zerem, 2014).

A key factor in the risk of death is whether the inflammation remains sterile or infection of the necrotic pancreas occurs.

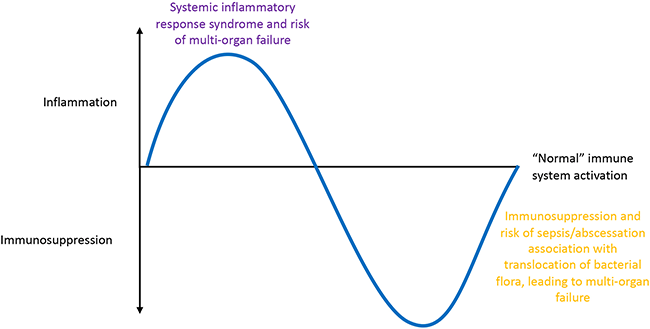

Two distinct phases of acute severe pancreatitis are recognised (Figure 1): an inflammatory phase characterised by systemic inflammatory response syndrome (SIRS) and a risk of multi-organ failure, followed by immunosuppression with the risk of translocated intestinal flora causing abscessation, leading to multi-organ system failure.

Pancreatitis causes more severe diseases than inflammation in other organs as pancreatic acinar cells contain digestive enzymes in an inactive form, packed as zymogens, that help prevent premature activation before they are released into the duodenum.

Enzyme inhibitors also exist within the pancreas (such as alpha-1-antitrypsin) and circulate in plasma (such as alpha-1-macroglobulins, alpha-1-antichymotrypsin and alpha-1-antitrypsin), aimed at limiting the internal pancreatic and systemic effect of these enzymes.

If inhibiting substances are blocked, or if enzymes are activated while they are still in the pancreas, autodigestion of the pancreas occurs. For example, inactive trypsinogen can be converted to active trypsin by enterokinase, bile or lysosomal enzymes.

Autodigestion disrupts the pancreatic membranes and is accompanied by arteriolar dilation, increased vascular permeability, oedema and haemorrhage, resulting in pain, leukocyte infiltration and peripancreatic fat necrosis.

If uncontrolled, pancreatic necrosis occurs with the potential for secondary infections by translocated intestinal bacteria. Arterial hypotension, portal venous pooling and hypovolaemia progressing to multi-organ failure, circulatory collapse and shock may ensue.

Leaking pancreatic enzymes can also cause extensive damage to other organs, including the liver, kidneys, lungs, heart and abdominal lymphatics.

Diagnosis

Diagnosis is based on a variety of factors, including history, risk factors and clinical examination.

A variety of risk factors for pancreatitis (Panel 1) are cumulative, which tend to increase (or decrease) the index of suspicion when presented with a possible case. Certain dog breeds also appear to be at risk (Panel 2).

- Pancreatic duct obstruction

- Duodenal/biliary reflux

- Pancreatic trauma/surgery – for example, abdominal trauma in a road traffic collision

- Pancreatic ischaemia/reperfusion (including anaesthetic associated):

- Hypothermia

- Hypovolaemia

- Ascending bacterial infection from gastrointestinal tract – especially cats

- Severe systemic disease:

- Sepsis

- Immune-mediated disease (dogs)

- Hypercalcaemia

- Hyperlipoproteinaemia

- Neoplasia

- Infectious agents:

- Toxoplasma

- Virulent strain feline calicivirus

- Babesia

- Drugs/toxins:

- Organophosphate intoxication, zinc ingestion

- Furosemide, azathioprine, sulphonamides, tetracycline, L-asparaginase, phenobarbital, potassium bromide, thiazide diuretics

- Corticosteroids – no longer generally considered a risk factor

- Obesity (potentially)

- Endocrinopathy (rarely acute):

- Diabetes mellitus

- Hyperadrenocorticism

- Hypothyroidism

- American cocker spaniel

- Cavalier King Charles spaniel

- Dachshund

- English cocker spaniel

- Fox terrier

- Miniature poodle

- Miniature schnauzer

- Miniature wirehaired dachshund

- Terriers

- Yorkshire terrier

Apart from biopsy, no single test shows 100% sensitivity or specificity for acute pancreatitis, hence diagnosis may have to be based on the balance of probability. Diagnosis of primary pancreatitis is generally based on the absence of other concurrent diseases that could act as a trigger.

While putting a name to a patient’s presentation helps discussions and explanations for the owner, and to some extent prognosis and future patient management (such as dogs kept on low fat diets), no specific treatments for pancreatitis exist and it is important not to lose focus on the need to support a potentially critically ill patient, rather than focusing on a search for a diagnosis.

When faced with a possible severe pancreatitis case, two key initial clinical questions must be asked:

- Is this pancreatitis?

- If pancreatitis is present, is it primary or secondary; if secondary, can I manage that initiating cause?

Clinical signs (moderate-to-severe disease)

No pathognomonic signs of moderate-to-severe acute pancreatitis (Figures 2a and 2b) exist. Commonly reported signs are often a general description of a sick or shocked patient:

- Despite the “acute” signs, patients may have a prior history of days/weeks of depression and anorexia – especially cats.

- Collapse, weakness, lethargy and dehydration.

- Mucosal pallor.

- Jaundice.

- Hypothermia – particularly cats – is more common than hyperthermia; many patients are normothermic.

- Tachycardia and hypotension.

- Tachypnoea and hyperpnoea, leading to dyspnoea.

- Vomiting (less commonly diarrhoea).

- Abdominal pain/abdominal mass.

- Ascites due to peritonitis.

Supportive findings

Supportive findings for pancreatitis include:

- Non-specific biochemical changes (for example, raised liver enzymes and bilirubin, pre-renal azotaemia, hypocalcaemia, electrolyte disturbances and hypoproteinaemia).

- Non-specific haematologic changes (for example, inflammatory leukogram [not always present], degenerative left shift and toxic changes [patient with SIRS], anaemia and thrombocytopenia):

- Some acute pancreatitis cases can have “normal” leukograms.

- Amylase and lipase of limited diagnostic value. Sensitivity/specificity of less than or equal to 50% (which is no more accurate than a coin toss). Trypsin-like immunoreactivity is a more specific, but not very sensitive test (approximately 35%).

- Positive pancreatic specific lipase or 1,2-o-dilauryl-rac-glycero-3-glutaric acid-(6’-methylresorufin) ester (DGGR) lipase.

- Elevated C-reactive protein (CRP) in dogs is supportive of systemic inflammation.

- Pancreatic imaging:

- Modality will depend on the patient, equipment and operator experience.

- Radiography can be of limited value, but may show a mass or evidence of localised peritonitis (such as loss of serosal detail); it can be useful in looking for evidence of other causes of the presenting clinical signs, assessing severity of disease or presence of concurrent disease.

- Where possible, ultrasound is the imaging modality of choice (typical findings in moderate-to-severe pancreatitis are shown in Panel 3 and Figure 3). Ultrasound also has value in looking for other primary abdominal diseases that may be causing the clinical signs, as well as abdominal disease that may underlie the pancreatitis:

- The sensitivity of abdominal ultrasound reported in 70 dogs with severe pancreatitis was 68%, compared to studies in cats with pancreatitis, which ranges between 11% and 35%. More recent studies of acute pancreatitis in cats with experienced ultrasonographers have suggested a sensitivity of 80% and a specificity of 88% compared to normal cats.

- CT and MRI scans generally offer limited advantage over ultrasound, as well as requiring anaesthesia and possibly contrast that can cause further pancreatic damage or exacerbate azotaemia.

- Identification of a pancreatic mass lesion is not synonymous with neoplasia.

- Cytology. Where clear changes in the region of the pancreas exist, fine needle aspiration may be of value in showing neutrophilic inflammation. The presence of intracellular bacteria is valuable in showing sepsis and suggesting likely poorer patient survival.

- Biopsy is definitive, but consideration must be given to the anaesthetic and surgical risk; it is rarely performed in cases of acute pancreatitis.

- Enlarged, hypoechoic pancreas

- Often surrounded by a hyperechoic area that represents peripancreatic fat necrosis

- With or without free peritoneal fluid that can be anechoic to granular

- Thickening of the pancreas

- Biliary changes:

- Dilated with or without tortuous bile ducts

- n Enlargement of the gallbladder

- Evidence of pancreatic masses:

- Abscess

- Pseudocyst

- Neoplasia

- Gastric wall oedema

Pancreas-specific lipase and DGGR lipase

The “diagnosis” of pancreatitis has increased markedly in recent times and it is now often associated as a comorbidity/intercurrent disease in a significant number of patients; many of these cases are chronic or show low-grade gastrointestinal (GI) signs.

For many patients, the diagnosis of pancreatitis is based on a positive pancreas-specific lipase (PL) or DGGR lipase test.

Studies have suggested around 90% agreement of the in-clinic SNAP PL test with external laboratory if canine PL (cPL) is elevated, and a 95% to 100% agreement if cPL is within the reference interval (that is, a positive sample supports elevated cPL; a negative sample is more questionable).

In cats, agreement between a SNAP feline PL (fPL) test and external fPL has been reported at 97.5% (Schnauß et al, 2018).

Relatively few studies exist that look at the true sensitivity and specificity of pancreatic lipase due to the lack of a definitive test, other than a pancreatic biopsy (and even then, regional pancreatitis is reported) to assess how many patients with a positive PL/DGGR lipase test have clinically significant pancreatitis.

As experience has developed with the assay, the cut-off and “grey-zone” levels have increased.

In one study of cPL in dogs without pancreatitis, 38 out of 40 were below the cut-off of 200μg/L and 1 was between 200μg/L and 400μg/L, giving a specificity of 97.5%.

The author’s experience is that some dogs with acute and chronic gastritis can have significantly high cPL, presumably due to cross-reactivity of gastric lipase. Even less information is available for the fPL assay, but it is assumed its sensitivity and specificity is similar.

Therefore, it is possible that a patient with GI signs and a positive lipase test may only have GI disease.

In acute pancreatitis, sensitivity of PL and DGGR lipase is around 80% to 85% (some acute cases will not have a positive test so a rule-out based on PL/DGGR lipase alone will miss 15% to 20% of acute pancreatitis cases).

The real specificity of the tests’ ability to demonstrate clinically relevant changes in the pancreas that are responsible for the patient’s presentation is unclear.

In dogs, the author combines the results of pancreatic lipase testing with CRP. If both tests are positive then the probability the patient has pancreatic inflammation sufficient to cause significant clinical disease increases; CRP is usually substantially elevated in theses cases (more than 80mg/L to 100mg/L).

If the pancreatic lipase testing is negative – or PL is positive, but CRP negative – then investigation for other underlying causes of the presentation should be undertaken.

If CRP is elevated, this at least demonstrates systemic inflammation as a likely cause of the patient’s presentation. If both pancreatic lipase and CRP are within reference interval then significant pancreatitis is unlikely.

Unfortunately, despite assessing alpha-1-acid glycoprotein, haptoglobin and serum amyloid A, the author has not found a reliable marker/combination of markers for systemic inflammation in cats.

Management

No specific evidence base exists for the treatment of hospitalised patients with acute pancreatitis. Therapy should, therefore, be patient and goal-directed, symptomatic and supportive.

As well as deciding which parameters should be monitored/measured and how often, key parts of the plan for all patients should include:

- pain management

- managing blood pressure and circulation

- control of nausea

- nutrition

Pain management

Pancreatitis can be extremely painful and sometimes difficult to assess in poorly responsive patients.

Opiates are sufficient in some patients, but their tendency to cause nausea and impact on gut motility should not be overlooked. If pain is mild, buprenorphine or butorphanol may be sufficient; moderate pain can be managed with methadone.

Where pain is severe, fentanyl may be sufficient, but often combination therapy is required such as fentanyl, lidocaine and ketamine, continuous rate infusion (CRI) or methadone, lidocaine and ketamine.

Managing tissue perfusion

Fluid therapy is essential and should be given intravenously. The aim is to maintain tissue perfusion – particularly of the pancreas – as well as hydration, urine output and blood pressure.

In many patients, the use of crystalloids, usually Hartmann’s solution, is sufficient. Monitoring electrolytes is important and potassium supplementation is often necessary – especially in anorexic cats.

Where blood pressure is not being maintained by adequate use of crystalloids, then colloids can be considered. In severe cases, for short-term management, pressor agents may also be required.

In patients with abdominal effusion, restricting fluids does not serve to reduce the effusion, nor should diuretics be used. A consequence of abdominal effusion can be significant hypoalbuminaemia, leading to a fall in oncotic pressure, often made worse by low cholesterol levels. Maintaining albumin concentration above 20g/L will ensure adequate oncotic pressure and improve capillary perfusion. If albumin falls below this level, options are:

- Plasma (but difficult to give enough):

- May have the added advantage of replenishing some anti-inflammatory proteins, protease inhibitors, antithrombin III and coagulation factors.

- Evidence of benefit of plasma on outcomes is lacking.

- Canine albumin (not readily available in the UK).

- Human albumin (anaphylaxis is reported, although this seems less likely when using albumin products in the UK than US).

Antiemesis

Most patients hospitalised with pancreatitis are either actively vomiting or markedly nauseated. Controlling nausea/vomiting as much as possible improves patient welfare, but also serves to increase the likelihood of being able to provide the patient with adequate nutrition.

A variety of antiemetics are available:

- Maropitant – effective and has the added benefit of anti-inflammatory properties (via blocking substance P), but may worsen gastric atony, which can be a major challenge with abdominal inflammation causing secondary ileus.

- Metoclopramide – can be very effective, especially as a CRI.

- Ondansetron – an effective antiemetic acting via antagonism of the 5-HT3 receptor. It can be given intravenously and is a useful adjunct if other antiemetics are ineffective or contraindicated.

Whether value exists in reducing the acidity of gastric contents in vomiting patients is unclear, but proton pump inhibitors such as omeprazole or pantoprazole can be considered given twice daily; they are significantly more effective in controlling acidity when compared to H2 blockers, such as cimetidine or famotidine.

Nutrition

Nil by mouth has been the classic approach to pancreatitis in the past on the basis of not stimulating the pancreas to produce or excrete more digestive enzymes.

No evidence of the benefit to this approach exists and it is likely that:

- the smell of food being given to other patients is sufficient to cause a pancreatic response

- not feeding the gut increases the risk of bacterial translocation

- negative nitrogen balance and weight loss worsen prognosis

The optimal approach to feeding is unknown, but current best advice is to feed as soon as the patient can cope with nutrition (usually once vomiting/nausea is controlled); tube feeding may be necessary.

In severe cases, the benefits of adequate nutrition need to be weighed against the risks of anaesthesia and fitting a jejunostomy tube. If this is performed then careful inspection of the pancreas and biopsy (if appropriate) should be undertaken.

Initially, feeding should be aimed at minimising the negative effects of starvation; to this end, 50% resting energy requirements should be the goal. Parenteral feeding should be avoided if possible.

Apart from using a highly digestible, energy-dense, palatable diet, no specific formulation is recommended, although for dogs the diet should also be low fat.

Other therapies

Many other therapies have been used in patients with pancreatitis, but their value is difficult to assess and in some cases may have a negative impact.

The blanket use of antibacterial agents is controversial and of no proven benefit. Antibacterial treatment is indicated if the patient is septic, shows evidence of SIRS or multi-organ failure, or shows other evidence of pancreatic infection (for example, through cytology).

Treatment with corticosteroids is very controversial and their use should be based on an individual assessment of the pros and cons for a specific patient.

In some specific cases, such as immune-mediated pancreatitis in cocker spaniels, corticosteroids are likely to be beneficial. In an uncontrolled study (Okanishi et al, 2019), dogs treated with prednisolone, compared to those that did not receive prednisolone, had an improved one-month survival.

Other potential therapies should be in response to the patient need, such as the presence of disseminated intravascular coagulopathy (DIC), acute kidney injury or haemolytic anaemia.

Many patients with pancreatitis are likely to be prothrombotic, so the use of antithrombotics and/or anticoagulants should be weighed against the potential risk of DIC developing. In extreme cases, surgery can be considered if gross necrosis, abscessation or marked exudative peritonitis is evident, or the patient is failing to improve with aggressive conservative management.

Owner communication

Owner communication is a challenge initially while the diagnosis is being established and when the patient is being treated.

Pancreatitis is one of those conditions where spending more money does not necessarily improve outcome and despite the best facilities, plan and patient care, a significant number of patients will not survive, and in some studies mortality approached 100% (such as cats with acute necrotising pancreatitis).

Although always a sensitive subject, discussing costs is critical, and having that conversation at the beginning is important for the owners and for you when developing a care plan. The challenge with pancreatitis is to give a meaningful estimate, and sometimes it can be more helpful to give an estimate for initial stabilisation and then the likely cost of each day spent in hospital.

Secondary complications in moderate-to-severe pancreatitis cases are also common, so updates can be something of a rollercoaster for owners. Often, the patient may show some initial improvement when a care plan has been developed and goal-orientated therapy started, but then a hiatus may occur where the patient does not seem to be improving.

While it is important to review the care plan to ensure it is appropriate, the temptation to change things or add more treatments should be avoided, and a clear message given to the owners that the right management is in place and the patient needs time to improve.

Making sure the owners are aware a “plan B” exists should their pet deteriorate is also helpful, although a detailed discussion of what this involves is often better avoided.

Owners are understandably sensitive to the pain and suffering of their pet, and being honest about the fact pancreatitis is painful and acknowledging their pet is likely to be in pain helps build trust, as it allows you to outline how their pet’s pain is being minimised by your management plan.

It is also helpful in being realistic about the likely rate of improvement and, in the author’s experience, to outline the key milestones ahead, such as controlling vomiting, getting the patient eating and being able to de-stage pain relief, as it allows positive steps to be acknowledged while recognising major hurdles that still lie ahead.

For many owners, having an early conversation about euthanasia, even though it is distressing, is also comforting; it will be on their mind anyway and it is important for them to know that you will not keep treating regardless of their pet’s condition or outlook. It also allows you to discuss whether resuscitation should be attempted.

In patients failing to improve, deteriorating or where secondary complications are developing, agreeing timelines and milestones is valuable as it flags up clear decision points for the future.

Conclusion

Regardless of experience, acute pancreatitis is a difficult condition to diagnose and manage, requiring all the teams’ skills to ensure the best outcome for the patient and owner, while acknowledging, even with the best care, a proportion of patients will not survive to discharge.

- Some drugs referenced in this article are used under the cascade.