6 Sept 2022

Addressing inappetence issues in hospitalised cats

Samantha Taylor explains how professionals can encourage felids to eat and why it is important to act rather than wait.

Figure 5a. Naso-oesophageal or nasogastric feeding tubes (5a) are among the most commonly placed feeding tubes in cats. Image © Lindsey Dodd

Inappetence (or hyporexia) is a common complaint reported by owners of cats presented to veterinary clinics. It can have a variety of causes, not just the underlying disease itself. Inappetence is also frequently an issue for hospitalised cats and should be promptly addressed as cats can be particularly vulnerable to the effects of malnutrition.

In view of the importance of nutrition in feline medicine – and particularly for hospitalised cats – the International Society of Feline Medicine (ISFM) put together a team of experts to author the 2022 ISFM Consensus Guidelines on Management of the Inappetent Hospitalised Cat.

When preparing the document, it was also clear that concise videos on placement and management of feeding tubes was needed for both owners and veterinary professions; hence, these were also created with the help of Royal Canin and Linnaeus (and can be found here – along with two owner information documents on feeding tube management and inappetence in general).

This article includes information from the guidelines (courtesy of ISFM), but for complete discussion, see the full version.

Unique nutritional requirements of cats

Cats are strict carnivores and have particular nutritional requirements related to their origins as hunters. They require a higher level of protein than other species and the rate of protein breakdown does not adjust to reducing intake, which can mean a rapid lean mass catabolism when inappetent.

In addition, protein requirements are likely even higher during critical illness and, therefore, hospitalised, unwell cats may be in a hypermetabolic state due to inflammation and sympathetic nervous system stimulation. Accelerated loss of lean tissue and starvation can negatively affect immune function, wound healing, gut health and recovery, and result in complications, such as hepatic lipidosis.

Managing an underlying disease is important, but neglecting nutrition can lead to suboptimal outcomes for our patients.

Causes of inappetence

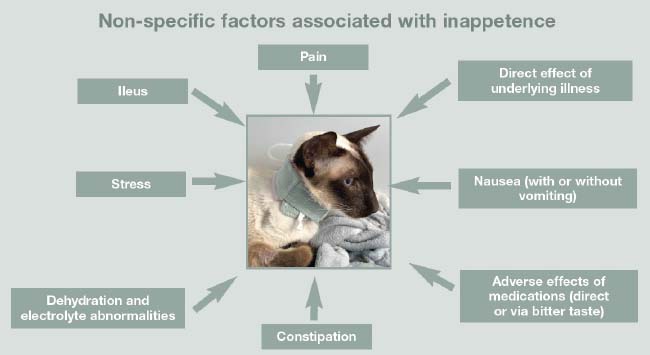

Numerous causes of reduced food intake in cats exist. Some are functional (for example, jaw injuries), but most relate to the primary disease process. However, other factors should be considered that may worsen and perpetuate inappetence (Figure 1). For example, pain, stress, nausea and gastrointestinal (GI) dysmotility may commonly affect hospitalised cats and should be managed alongside the disease process.

Some causes of inappetence are easily overlooked, such as giving multiple oral medications, bitter medications (in food or into the mouth), adverse effects of drugs (such as opioids and antibiotics), as well as electrolyte abnormalities, dehydration and constipation.

Each case should be assessed not only for effective treatment of the underlying condition, but also for these complicating factors that will stop a cat eating, resulting in suboptimal recovery. The guidelines include a table of drug doses for the management of nausea and GI dysmotility.

Reducing stress in hospitalised patients to encourage voluntary food intake

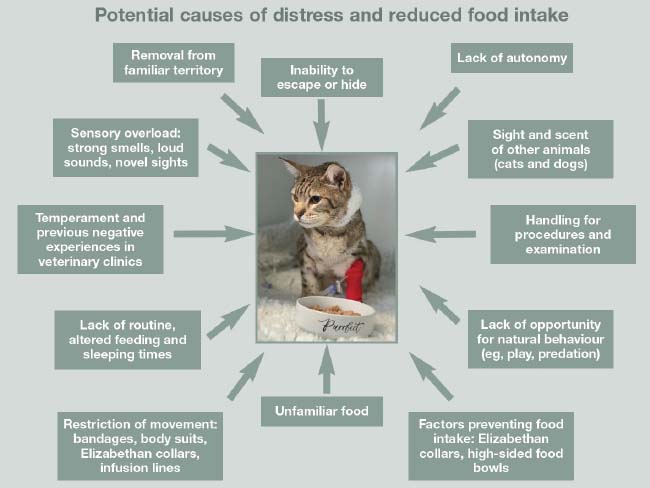

It is clear stress is a cause of inappetence in cats in veterinary clinics. However, much can be done to reduce anxiety in terms of how we feed, as well as how we manage inpatients.

Reducing stress will encourage cats to eat, potentially avoiding further interventions and shortening hospitalisation.

A cat-friendly ethos should be at the centre of care, aiming to avoid as many environmental and interaction stressors as possible. Proactive interventions, such as placing feeding tubes, can actually reduce stress by negating the need to offer food, tablet the cat, and preventing physical deterioration that will affect mental well-being. Some factors causing stress are illustrated in Figure 2.

Tips to reduce stress include:

- Make human interactions as positive as possible; move slowly and quietly, and be calm and gentle.

- Never forcibly restrain a cat, avoid pinning or crushing and never scruff; consider sedation instead.

- Allow hiding in the cage (Figure 3) and during procedures, for example, give the cat the option of hiding its head under a towel and gently extract/access the area of interest.

Figure 3. All hospitalised cats should have a place to hide. - Offer the cat’s own familiar food, ideally in a familiar bowl; liaise with the caregiver to discuss preferences or use a questionnaire (provided in the toolkit via the link mentioned previously).

- Feed in shallow ceramic bowls.

- Remove uneaten food within half an hour (unless the cat is a “secret” eater and eats at night).

- Separate resources, keeping the food away from water and litter tray as much as possible; “dividing” even, small spaces with hiding areas (even the cat’s own carrier) can help.

- Offer food at room or body temperature.

- Use soft Elizabethan collars that allow cats to still eat (Figure 4) and have supervised time without the collar.

Figure 4. Use soft Elizabethan collars and consider supervised periods without them to encourage cats to eat. - Create positive clinic experiences; if the cat enjoys a stroke, groom or hand feeding, then this may maintain a positive emotional state in which the cat is more likely to eat.

Nutritional assessment of hospitalised cats

Nutritional status should be measured as the fifth vital assessment (after temperature, pulse, respiration and pain assessment), and should be evaluated in every hospitalised patient (ideally, every patient).

It allows identification of cats needing nutritional support or at risk of needing support. It enables decisions to be made on feeding method, food type and urgency of intervention.

Factors to consider in a nutritional assessment include:

- dietary history

- clinical history and examination

- weight and body condition score

- muscle condition score

- specific clinicopathological parameters, such as albumin and creatine kinase

- underlying disease, and predicted duration and severity

Nutritional assessment and dietary history should be included on hospital sheets and repeated regularly during hospitalisation as the patient’s clinical condition and need for intervention may change.

Taking a nutritional history: why is this important?

A dietary history is part of a nutritional assessment and for hospitalised cats, it is even more important to know what they normally eat.

Food preferences can be formed in the pre and peri-natal period, and when in unfamiliar settings cats may be even less flexible, preferring familiar foods, and refusing “recovery” or prescription novel diets. For example, cats used to eating dry food may refuse wet food and vice versa. Without knowing the cat’s dietary history, refusal of new diets may be mistaken as hyporexia. The guidelines toolkit includes a dietary history form for clients to complete to save time in busy clinics.

Appetite stimulants

Appetite stimulants can be helpful in improving voluntary food intake. However, they are not a replacement for a diagnostic workup, and management of other factors such as pain, nausea, stress, dehydration and ileus.

Interventions such as feeding tube placement should not be postponed for long to assess the effect of appetite stimulants. Indications and contraindications are found in Panel 1.

Indications

- Short-term use during diagnostic workup to maintain food intake.

- Behavioural or environmental causes of inappetence (for example, during a house move).

- Supportive care during acute and chronic disease management; for example:

- chronic kidney disease

- in cats showing some interest in food

- in cats that are eating, but caloric intake is not sufficient

- If placing a feeding tube is not possible for various reasons.

Contraindications

- Critically ill patients.

- Active vomiting, regurgitation or nausea (nausea may be subtle in cats, treat if in doubt).

- Unable to eat or swallow.

- Uncontrolled pain.

- Unmanaged gastrointestinal dysmotility.

Two approved drugs are available for cats: mirtazapine and capromorelin. Other drugs, such as steroids (anabolic, corticosteroids), megestrol acetate, benzodiazepines and B vitamins haven’t been assessed for efficacy, and some may have significant adverse effects.

- Mirtazapine: oral and transdermal mirtazapine is available in many countries, and can be an effective appetite stimulant, as well as having a likely antiemetic effect. Smaller, frequent doses (2mg/cat/24 hours in the absence of contraindications) can avoid adverse effects.

- Capromorelin: a ghrelin receptor agonist, acts directly as an orexigenic drug, effective as an appetite stimulant. It should be used with caution in patients with diabetes and not in acromegaly, and cautiously in hospitalised patients as transient bradycardia and hypotension has been reported. Elura is licensed in the US and can be used in the UK only via the cascade.

Feeding tubes

Nutrition can be provided via feeding tubes, which can also be used to allow medication administration without stress. Early use of feeding tubes can prevent malnutrition, and cats can be discharged with oesophagostomy (O) tubes and gastrostomy tubes in place.

The most commonly placed feeding tubes are naso-oesophageal (NO), nasogastric (NG) and O tubes (Figure 5). See the guidelines for the advantages and disadvantages of each type of tube and guides, and videos on placement of NO/NG, and placement and care of O tubes.

When to consider placing a feeding tube

The decision to place a feeding tube depends on nutritional assessment of the individual case, owner finances and cat temperament, but in general, many cases and situations exist where a cat would benefit from the consistent nutrition provided. Fluid and medications can also be administered via the tube. It should be considered in the following situations:

- Patients consuming less than 80% resting energy requirements (RER) for three days or more (especially if associated with weight loss).

- Cats physically unable to consume RER voluntarily (for example, jaw fractures).

- Cats with anticipated inappetence (for example, following surgery or during chemotherapy).

- Cats at high risk of malnutrition or overtly malnourished.

- To facilitate medication compliance – particularly during prolonged treatment (for example, O tube for medicating cats with mycobacteriosis).

Complications of feeding tubes

The majority of feeding tubes are well tolerated without complication. However, tube dislodgement and obstruction, as well as stoma site infection, are the most common. Tube obstructions may be managed by flushing and aspirating with warm water (body temperature), and a solution of a quarter teaspoon pancreatic enzymes and 325mg bicarbonate in 5ml water, left in the tube for a few minutes, can be effective.

Anecdotally, carbonated drinks have been used; however, consider that these products will be flushed into the oesophagus/stomach. Prevent obstruction by ensuring food is liquid consistency and liquidised well, the tube is flushed before and after feeding, and medications are well-crushed and dissolved prior to administration. Stoma site infections (Figure 6) can be managed with increased frequency of dressing change and cleaning with antiseptic solutions, and in more severe cases, systemic antibiotics and debridement in the case of abscess. The tube may need to be removed.

Prevent infection by placing aseptically, securing to avoid tube movement, avoiding over-tight sutures, meticulous hygiene and use of antimicrobial discs at the stoma site. Other complications are discussed in the guidelines.

What diet and how much to feed?

Diet choice may depend on tube type as NO and NG tubes necessitate liquid diets. Recovery/convalescence diets are suitable for most cats as they contain increased amounts of highly digestible protein, but most diets can be liquidised/blended into a slurry and fed via larger bore O tubes.

The primary purpose of nutritional support is to stabilise a patient’s nutritional status, rather than replenish lost condition, and feeding amounts should be conservative, aiming to meet RER within three days of initiating nutritional support, if tolerated. Illness factors, or feeding for ideal bodyweight, is not recommended, and cats should be fed for current bodyweight, adjusting by a maximum of 10% every 48 to 72 hours according to weight loss or gain. For cats that are debilitated or have suffered a long period of subnormal appetite, refeeding syndrome is a risk and so nutrition should be instigated more slowly – starting, for example, at 20% RER on day one and increasing to RER over four to 10 days, depending on response.

Feeding volumes and response should be recorded, and a record sheet is provided in the toolkit. Frequency of feeding depends on patient factors such as tolerance to feeding, volume and calories required. Constant rate infusions (CRI) can be better tolerated than bolus feeding by some patients with vomiting/regurgitation. The maximum bolus volume is 5ml/kg to 15ml/kg, and between 3ml/hr and 8ml/hr for CRI feeding.

Cat-friendly tube feeding

It is important that feeding is a positive experience both in hospital and at home. Hospitalised cats can be fed in their cage or moved to a consultation/examination room. Avoid any contact (sight, sounds, smells) of dogs:

- Allow cats to relax and try to elevate their heads before feeding.

- Some cats like to hide, and leaving some length on the tube can allow them to move away and still be fed (for example, in an igloo bed or under a loose blanket).

- If a cat resents handling, do not use enforced restraint. Consider placing the cat in a carrier and review analgesic, antiemetic and anxiolytic therapy.

- Feed slowly, as rushing can cause nausea and negative associations with feeding.

- Watch for discomfort, lip licking, excessive swallowing and trying to move away.

- Reassure the cat with quiet, calm words; stroking (if accepted) may be beneficial.

- Food should be warmed to body temperature; mix well to avoid hot or cold spots.

- Ensure appetite has returned for three to five days before you remove the tube (O tube, G tube). NO/NG tube can deter voluntary intake, so may need removal to assess appetite (replacing if inadequate).

Conclusion

To optimise our patients’ recovery from illness, we must manage inappetence.

It is very tempting to wait another day to see if the cat eats, but delay means missed opportunities to address inadequate nutrition. Intervention at an earlier stage should be considered for our feline patients failing to meet their RER – particularly during hospitalisation, but also at home.

Placement of feeding tubes can be straightforward, and help reduce hospitalisation time and optimise recovery.