7 Feb 2021

Laura Lacey details the disease processes that can affect small animal patients as they get older, and the importance of sharing with owners what is normal and what is not.

Image © methaphum / Adobe Stock

Age is not a disease, but sadly many disease processes exist that affect us more as we age. It is important owners are informed about what is normal and what is not. Some diseases and disorders have slow, chronic progressions that are easily mistaken for “they’re just getting older” and at the point when the owners realise a true problem is presenting, it may be too late for us to make significant improvements to the quality of life of our patients.

Getting old is a gift; a privilege denied to many – a very true phrase for sure, given the recent global pandemic. Many times, lives are sadly cut short – and we are very aware our companion animal lives are never as long as we would like them to be.

Advances in veterinary medicine have meant lifespans have increased dramatically over the years. The average lifespan of domestic-owned dogs is 12 years (O’Neill et al, 2013) and 14 years in cats (O’Neill et al, 2015), with some cats living into their 20s.

Cross-breeds and mixes have the greater longevity, but it has also been proven neutered dogs live longer than unneutered ones, with the greatest gain being for females (Woodmansey, 2018). The discussion relating to the best time for neutering is outside the scope of this article.

Many milestones occur in our patients’ lives where we think about making changes. At certain ages we start to suggest senior diets or senior wellness checks, and for others we strongly advise preanaesthetic blood tests and IV fluid therapy if a general anaesthetic is needed. These will vary from species to species and according to their type; a large-breed dog is considered senior long before a small-breed dog. The basis for this is increased incidence of adverse occurrences.

Boosters and annual health checks performed by the vet are an essential way to get our patients examined, but is this frequent enough? Significant deterioration in conditions can occur in 12 months. Also, are clients actually wanting to discuss “minor” ailments with the vet at these visits? Is the waiting room full of clients, adding to time pressures for everyone?

As we have found recently during lockdown, many of us have been running behind with routine work. Limited interactions with clients outside of the consult room, while still treating patients to high standards, has been challenging.

Nurses are perfectly positioned to advise clients further on age-related changes and the clinical signs that may give us early indications of encroaching disease processes. Nurse clinics allow us time to discuss concerns, and provide plans and support for treatment that is required.

Laterally thinking for current times, we are also able to offer this support remotely via telephone or video calls. This can mean we are still able to help support our patients as they age. Many healthy pet club plans offer a six-month check-up, which may be taken with a vet or a nurse. Could this be offered to many more of our clients to encourage them to discuss concerns with a professional?

A diagnosis can only be made by a vet; however, nurses can provide support to clients as they consider their options when it comes to how to implement treatment and monitoring of conditions.

We are also invaluable for allaying fears when clients are not sure if something warrants a vet check. If the client has taken the time to call the clinic about it then it is obviously of concern to him or her, so we need to ensure we listen.

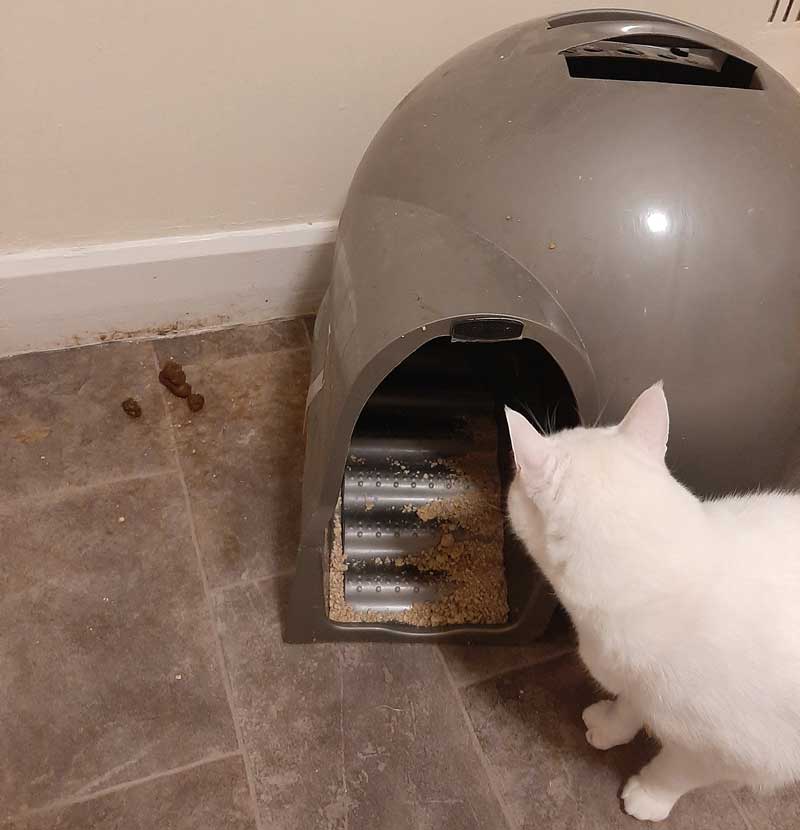

Sometimes a throwaway comment can actually highlight something more significant to us. It may be something simple, such as a “naughty cat peeing next to the litter tray”, which could make us think about pain or arthritis, for example. Further questioning and investigation may be appropriate. Written questionnaires may even be used at this time.

There could be obvious concerns an owner may have, such as lumps developing, and we know that the incidence of tumours increases as an animal ages. Commonly, we see dogs with warts and lipomas; benign and malignant tumours of the skin or the layers just below. These are easy for owners to see and will be highlighted quickly. Investigations will be needed to identify them correctly, and surgical removal may be suggested.

Mast cell tumours are the most common malignant tumour seen in dogs. They may be seen in dogs of any age, but occur most commonly in dogs 8 to 10 years old. They may develop anywhere on the body surface, as well as in internal organs, but the limbs, lower abdomen and chest are the most common sites. In about 10% of cases, tumours are found in multiple locations.

Tumour size at the time of surgery often predicts the outcome; tumours larger than 3cm are associated with decreased survival time (Villalobos, 2018).

Benign tumours are often left undisturbed in elderly animals, as the risk of anaesthesia may outweigh the benefits of removal. Nurses can help owners to monitor such lumps and advise if they need addressing in the future, such as if they become damaged or ulcerated from pressure or encroach on mobility.

Internal tumours may not be so easy to identify, often only presenting clinical signs when they are significant in size or have caused sufficient damage. Screening blood tests may help to identify some of this damage at a slightly earlier stage if specific organ damage is apparent or blood cells are involved. Wellness or screening blood profiles can help to identify changes within the body prior to obvious clinical signs presenting (Table 1).

| Table 1. A very brief overview of a wellness profile | ||

|---|---|---|

| Test | Looks at | Could indicate |

| Complete blood count | White and red blood cells | Anaemia Inflammation Infection Immunosuppression Hydration status |

| Biochemistry | Blood urea nitrogen and creatinine Alanine aminotransferase, aspartate. aminotransferase, alkaline phosphatase, and bilirubin Amylase and lipase Total protein and albumin tests Cholesterol |

Renal function Hepatic functionPancreatic exocrine function Liver and renal function Several endocrine disorders |

| Electrolytes | Sodium, potassium and chloride | Fluid balance, neuromuscular and heart function |

Arthritis and other degenerative bone disorders in cats are under-diagnosed compared to dogs. In one study, published in 2002, 90% of cats older than 12 years of age had evidence of degenerative joint disease (International Cat Care, 2018). It is often overlooked due to the nature of cats’ lifestyles.

Dogs are actively walked and encouraged to move, whereas cats’ activity levels may be misinterpreted and perceived to just be getting older and sleeping more. Several subtle signs exist that we can advise clients about when considering their older cat’s behaviour (Panel 1). Owners of dogs are far more likely to broach any mobility issues noted and actively look for solutions.

Reduced mobility

Reduced activity

Altered grooming

Temperament changes

Full investigations may be offered to get a definitive diagnosis, including radiographs, but these may not be an option for all clients for a number of reasons. A pain relief trial could be implemented and it can be really useful for nurses to help monitor this alongside the owner.

Making sure an owner is aware of signs of improvement is essential, and a simple chart can be created and personalised. We can also make suggestions to help improve the environment. We may need to look at assistance for the pet getting up and down on to furniture, or, in a cat’s case, review its toilet facilities. Accidents outside of the litter tray (Figure 1) may be due to compromised access, such as too high a tray to climb into or even discomfort when balancing to squat in deep litter.

Toilet mishaps are commonly mentioned in older pets. Polyuria may be associated with true incontinence as muscles weaken in time or it could be linked to an infection as the immune system starts to deteriorate. Polydipsia linked to the polyuria may be indicative of metabolic disorders starting.

Urine samples should be offered annually to our senior pets as they can give us good early indications of several conditions, including renal compromise and diabetes. In a study completed on apparently healthy older dogs in 2017 by Willems et al, it was demonstrated that early signs of chronic kidney disease were often present many months before diagnosis, but it did not encourage the owner to consult a vet.

Making owners aware of what they should observe, such as normal urine output (1ml/kg/hour to 2ml/kg/hour), as well as water intake (50ml/kg/24 hours) can help us to diagnose conditions earlier. As urine samples are relatively cost-effective and non-invasive, clients may be encouraged to present them for their pets in the first instance. Any irregularities can then be highlighted to the vet for further diagnostics to be performed.

Appetite can be a really useful indicator of health as an animal ages. Polyphagia is a vague sign that may appear, and we know certain diseases – such as hyperthyroidism in cats, and diabetes – can increase appetite, but many reasons exist for why it could occur.

We would commonly expect appetite to decrease as our pets age due to their reduced exercise. Looking at patterns regarding their eating habits and weight changes can help determine what is happening. If an increased appetite and weight gain occurs then we need to monitor this and see if it is relating to boredom or reduced exercise, for example, or something more significant, such as ascites.

It may be something we can address in nurse clinics as additional weight will impact on and exacerbate any joint issues that have or are developing. Increased appetite with weight loss, or a decreased appetite and weight gain, certainly need investigating further.

The crucial point here is communication and regular monitoring. It can be very hard for an owner to identify weight loss or gain when he or she sees the animal every day (Figure 2).

Nutritional demands also change as our pets age. The need for high‑quality, easily digestible food is universal; however, more specific changes may be needed to facilitate compromised body systems. This is an area where nurses can excel, as they can explain how the patient’s diet can be adjusted and how to get it to accept these changes.

The details regarding senior diets are complex and beyond the scope of this article, as the options are vast. This can seem overwhelming for us at times, so we need to be mindful of how owners may feel.

Keeping a plan simple is the best option to start with. We may suggest supplements that we can add into their existing diet that are commonly used to support joint or skin health (Figure 3). Sticking to well-recognised and easily understood food products helps ensure a balanced diet is provided consistently.

We can find a high demand for our time may exist with older pet discussions as some of our patients may need multiple areas addressing, such as regular weight checks, and many will require support with dental health. Commonly, bad breath is assumed to be “normal” in an older pet, but we know it represents bacterial buildup and systemic disease.

Periodontal disease affects more than 87% of dogs and 70% of cats older than three years of age (RVC, 2002), so by the time our pets are elderly they may be at a considerably advanced stage of disease. If left unchecked, periodontal disease can have a severe impact on further body systems, such as cardiac and renal.

Other clinical signs that are often considered stereotypical of our elderly pets are associated with brain ageing. We may see dramatic signs, such as vestibular episodes, that can be associated with brain ageing and will inevitably be addressed by a vet. Subtle slower deterioration may be exhibited by behavioural changes and is now well-documented in dogs; however, further investigation is being undertaken in cats.

Ageing dogs and cats show many similarities in terms of brain changes, but also some important differences (Vite and Head, 2014). Changes in appetite, routine, increased vocalisation, a loss of toilet training and learned behaviour skills can all be indicative of these changes. There is rarely anything we can do to reverse the damage, but we can advise clients how they can help try to potentially slow the deterioration.

Deterioration of the senses due to age can also be masked in these instances or linked. Failing eyesight and hearing may be primary or associated with the brain changes. Whatever the cause, we can try to assist them in adapting to the changes and ensure a good quality of life for the whole family unit.

We shouldn’t overlook other species when planning wellness clinics. Rabbits are commonly living up to 12 years in good homes, and owners are more and more committed to their long‑term health care. We are seeing more incidences of rabbits attending clinics for mobility issues as they are prone to arthritis in their latter years, and 30% of rabbits are now classified as obese (PDSA, 2019), so clearly further education and support is needed.

As nurses, we are able to offer support to pet owners that can really help to ensure the later years in an animal’s life are just as fulfilling as the rest. The time taken by nurses to explain situations and make sure owners understand the options available to them is crucial to positive treatment outcomes.

RVNs can also make really good use of their time performing Schedule 3 procedures, such as taking blood samples, as well as monitoring of blood pressure. Consultations with the vet are commonly around 10 minutes to 15 minutes long, which is often insufficient time to deal with a multitude of age-related concerns.

The team approach and offering clinics that owners can attend to discuss their concerns can really help to bond clients to a practice, increase revenue and, most importantly, make for a happy, older pet population.