9 Dec 2020

Analgesia advances: latest thinking and innovations

Karen Walsh discusses early recognition of this issue, as well as developments in medications and additional management options.

Pain assessment and management is an evolving field, with many changes over the past 10 years.

This article will look at the following areas:

- early recognition, quantification and treatment of pain

- multimodal analgesia

- innovations in pain medications

- adjunctive and non-pharmacological pain management options

Early recognition and quantification of pain

Recognition, quantification and treatment of pain is among the most common conditions that small animal practitioners must deal with in general practice.

In surveys carried out at emergency clinics, between a third (Rousseau-Blass et al, 2020) and half (Wiese et al, 2005) were recorded as showing signs of pain. In the Rousseau‑Blass et al (2020) study, the distribution of pain types was described as dermatological (67%), neurological (62%) or orthopaedic/trauma-related (54%).

Early recognition and treatment of pain helps to decrease the likelihood of chronic pain developing.

The intensity and duration of pain experienced by people recovering from surgery is an indicator of the likely development of chronic pain (Grubb and Lobprise, 2020). No reason exists not to believe this would be different for our veterinary patients – making it vitally important we recognise and treat pain promptly.

Recognising pain and assessing treatment success using scoring systems may allow a more objective measurement of effect. Owners’ perception and descriptions – coupled with videos of patients – are an important tool in assessing pain away from the veterinary clinic. The following tools help to obtain the information clinicians need to establish a problem list and treatment plan for each patient:

- Musculoskeletal Pain Screening Checklist in cats

- Canine Brief Pain Inventory

- Liverpool Osteoarthritis in Dogs

- Feline Musculoskeletal Pain Index

Multimodal analgesia

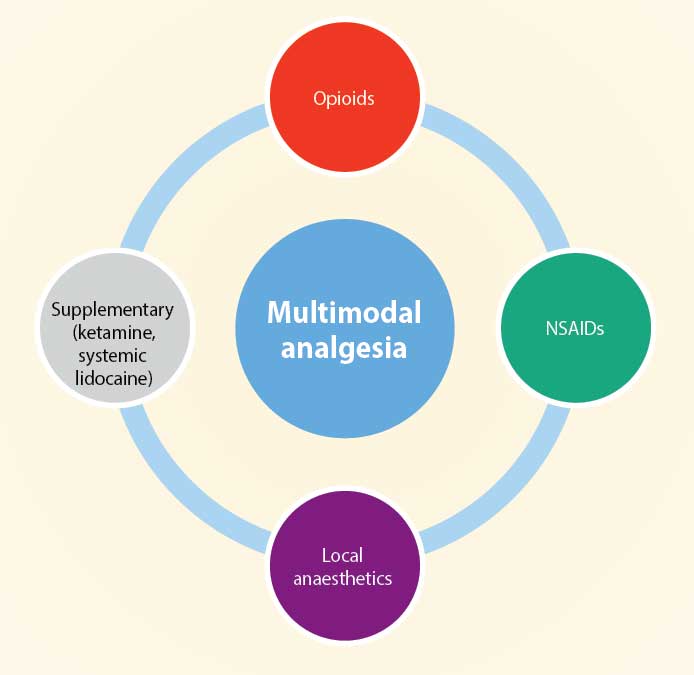

Multimodal analgesia involves using analgesics from different drug groups with the aim of reducing the total amount of each drug and improving the analgesic outcome for the patient.

Reducing the dose of any drug will hopefully lower the risk of side effects associated with high doses of certain drugs. Using this type of analgesic protocol will also reduce the reliance on one group – for example, opioids – to provide analgesia.

The move away from reliance on opioid use has been initiated in human pain therapy because of the opioid crisis in many countries. This has meant the availability of opioids has been reduced or intermittent in some localities, leading vets to use non-opioid methods of analgesia (Murrell, 2014; Figure 1).

Assessing pain

To monitor a problem, it is important to assess it – so the first step towards analgesic therapy is always to assess for pain and comfort.

Using a pain assessment tool will help to minimise differences between observers – and if they have an intervention level built in, such as the Short Form Glasgow Composite Scale, this will prompt clinical staff to intervene with analgesic therapy.

Different tools are available for assessing chronic and acute pain. Chronic pain assessment often focuses on quality of life assessments.

Pharmacological therapies

Local anaesthetics

Local anaesthetics have been classically used to block nociceptive messages travelling up the sensory nerves to the spinal cord; therefore, they are one of the most complete forms of analgesia.

They have become more commonly used in companion animal analgesia when used to perform nerve blocks (Figure 2) – for example, sciatic and femoral. They can also be used to produce regional analgesia, such as with epidural or spinal injections.

The literature concerning local anaesthetic use in companion animals is increasing daily and the methods used to monitor placement of the drug have increased, as ultrasound is now being used to visualise the site of placement. The aim of this directed placement is to achieve a better level of sensory and motor blockade, and a more complete analgesia.

The use of some form of local anaesthetic technique provides more complete analgesia, resulting in:

- reducing the perioperative anaesthetic requirements

- reducing the opioid requirements perioperatively and postoperatively (Palomba et al, 2020)

- better-quality recovery from general anaesthesia

- improved postoperative pain control (Grubb and Lobprise, 2020)

A survey of analgesia usage in UK vets in 2013 revealed widespread use of opioids (81% to 90%) and NSAIDs (98%) for routine surgeries, but only 20% of practitioners used local anaesthetic techniques in these cases (Hunt et al, 2015).

The reasons for this were not investigated, but possibilities are fear of side effects, unfamiliarity with techniques and lack of equipment available to perform some of the more complex blocks.

Intraperitoneal local anaesthesia

A recent capsule review was published in the Journal of Small Animal Practice from the WSAVA Global Pain Council regarding intraperitoneal and incisional analgesia (Steagall et al, 2020).

In this review, they concluded both incisional and intraperitoneal local anaesthetic should be used in any type of abdominal surgery. They went further to suggest that bupivacaine (not licensed for animals in the UK) could be used in sterilisation programmes, especially in countries where other analgesics may be limited.

The recommendation is that it is used as part of a multimodal analgesia protocol.

The problem with the evidence now is that many of the studies that have been conducted have variations in surgeon, anaesthetist, pain assessment, drug doses and local anaesthetics, which does not allow true comparison.

Ketamine

Ketamine was originally developed as an anaesthetic drug in the 1960s (Bell and Kalso, 2018); however, it is now often used as an analgesic.

Analgesia is reported to occur at subanaesthetic doses, but even with human pain management, no clear consensus exists regarding dose and duration of action.

The analgesic effect is thought to be primarily associated with interaction with the N-methyl-D-aspartate (NMDA) receptor in the CNS. Central sensitisation and amplification of pain signals, as well as some involvement with opioid tolerance, have all been linked to the NMDA receptor. As ketamine blocks this receptor, the aim is to reduce all these possible effects.

In the consensus guidelines regarding IV ketamine use in humans (Schwenk et al, 2018), they reviewed the evidence for the rational use of ketamine in different situations. Some of the evidence was weak due to lack of randomised controlled trials (RCTs). This situation in veterinary medicine is even more reliant on clinical experience and anecdotal reports as we do not have many RCTs with significant numbers, particularly for treatment of chronic pain.

The doses that have been used for analgesic therapy in veterinary patients are 0.5mg/kg to 1mg/kg as a bolus and 10mcg/kg/min to 60mcg/kg/min as a continuous rate infusion. Using human guidelines as a baseline, using the lower end of the dose range will be effective with fewer side effects.

It may be useful to consider ketamine in all surgeries that are considered moderately to severely painful as part of the multimodal analgesic plan. Many vets may already be doing this if they are using a triple or quadruple combination for sedation and anaesthesia.

Innovations in pain medication

Anti-nerve growth factor

Nerve growth factor (NGF) is important in the survival of sensory and sympathetic neurons in the prenatal and early post-natal period. It continues to have a function in the adult involving modulation of nociception. It works both at the level of the nociceptor and the dorsal route ganglion. Evidence exists that it may contribute to driving chronic pain (Enomoto et al, 2019).

Work has concentrated on using monoclonal anti-NGF antibodies that target the production of NGF. The monoclonal antibodies (mAbs) are species-specific, as mAbs from one species can result in adverse immune response in another.

One such mAb (bedinvetmab) has recently had a positive opinion from the European Medicines Agency (EMA), suggesting it may be released as a veterinary medicine soon. These drugs specifically target pain associated with OA and would be administered once monthly. The data submitted was considered by the committee to provide clinical improvements in pain and quality of life in dogs with mild to moderate arthritis (EMA, 2020).

Feline-specific anti‑NGF mAbs also exist – one of which was shown to produce a positive improvement for six weeks after administration to cats with degenerative joint disease (Gruen et al, 2016). Work is ongoing developing NGF mAbs for use in cats.

Anti-NGF mAbs have been associated with side effects in humans when they have been trialled for treatment of arthritis. These included peripheral oedema, arthralgia, extremity pain and neurosensory symptoms – most of which were transient and resolved within one month (Enomoto et al, 2019).

However, studies in humans were halted for a time when rapidly progressive OA was reported. An increased incidence of this appeared to exist in patients that were receiving concurrent NSAIDs.

The likelihood of a similar condition occurring in dogs and cats cannot be ruled out, and further research would be required.

Grapiprant

Grapiprant is a member of the prostaglandin receptor antagonist group of drugs. It specifically targets the EP4 prostaglandin receptor, which is thought to be a key part in the prostaglandin E2-mediated sensitisation of sensory nerves and prostaglandin E2 inflammation.

The aim of using such a specific drug is to minimise the potential side effects that are seen with NSAIDs, but still achieving pain relief and anti-inflammatory action.

It is a relatively new drug on the market (2018) in Europe and much of the evidence is reliant on experimental data. One experimental study compared grapiprant to firocoxib in an acute arthritis model and found it did not perform as well as firocoxib in that situation (de Salazar Alcalá et al, 2019).

This study was funded by the maker of Previcox. It will be interesting to see more independent clinical research to establish efficacy with client-owned dogs and the incidence of adverse events over time.

Cannabinoids

Cannabinoids have been of interest to medical pain specialists for some time, which, in turn, has led to interest in using them for companion animals that may be experiencing chronic pain.

Preclinical studies in a wide variety of pain models have demonstrated these drugs may have a dissociative effect on the pain pathways. Some synthetic cannabinoids have also been licensed for specific uses in humans.

The two active cannabinoids with the strongest evidence for analgesia are tetrahydrocannabinol (THC) and cannabidiol (CBD). THC also has psychoactive effects.

As with other types of analgesics, it is important to look at the type of pain being treated, as a recent meta‑analysis in human medicine did not find significant evidence to advocate the use of cannabinoids in neuropathic pain. However, the use of these drugs needs to be balanced against the possible side effects, such as psychosis/behavioural changes.

Although interest exists in their use in our species, no licensed products are available. Since September 2018, CBD products have been classed as a veterinary medicine, meaning it is illegal to administer an unauthorised product containing CBD without a veterinary prescription. It is possible for vets to prescribe a human CBD product under the provisions of the cascade.

Some studies have been conducted to establish whether a quantifiable analgesic effect exists in dogs. One such study used an oil‑based product at a dose of 2mg/kg twice daily and found a beneficial effect compared to placebo (Gamble et al, 2018). The authors pointed out the form in which the drug is delivered may influence blood levels, as well as different preparations containing different levels of CBD.

Non-pharmacological management options

Interest in non‑pharmacological therapies for chronic pain is growing also in our veterinary clients.

In the latest draft guidelines by the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE), for treatment of chronic pain in humans, it was noted no medical pharmacological or non‑pharmacological intervention was helpful for more than a minority of patients (NICE, 2020). However, it was acknowledged in these draft guidelines that adjunctive therapies – including weight loss, exercise and other physical therapies – may be helpful in allowing patients to live a more normal life.

Physical therapy/rehabilitation

Exercise is one of the modalities described in the NICE draft guidelines for treatment of chronic pain.

In humans, regular exercise is effective in treating pain. However, an acute episode of pain can exacerbate painful conditions (Sluka et al, 2018). Exercise may change the central pain inhibitory pathways protecting against a peripheral painful insult.

Consideration of exercise should be part of the treatment plan for any painful condition, including in companion animals. More formal rehabilitation with a physiotherapist, who will devise an exercise plan for the pet that is appropriate to the level of pain, can be beneficial to a patient’s overall progress.

Acupuncture

Acupuncture (Figure 3) can be defined as the insertion of a solid needle into the body with the purpose of therapy, disease prevention or maintenance of health.

In the UK, acupuncture is an act of veterinary surgery. The mechanism of action of acupuncture is not fully understood, but an intact nervous system is a requirement for it to work.

It appears some effects are mediated by endorphins and other opiates (opiate antagonists such as naloxone can block the effect of acupuncture). Evidence also exists that acupuncture upregulates messenger RNA for pre-encephalin; this is likely to be the mechanism of the increasingly prolonged effects of acupuncture over time.

The placement of needles stimulates Aδ fibres associated with acute pain, meaning the onward transmission from C-fibres is suppressed and, therefore, chronic pain is decreased. This is most effective when the needle is placed near the source of the pain.

Different forms of acupuncture exist, with dry needling and electroacupuncture the most used in veterinary medicine.

Evidence for the effectiveness of acupuncture has not been easy to establish, but a meta‑analysis published in The Journal of Pain concluded evidence existed for the use of acupuncture to treat chronic musculoskeletal, headache and OA pain. It also concluded the effects of acupuncture persisted over time and was not explained by placebo effect (Vickers et al, 2018). An evidence review of efficacy in animals concluded further trials of high quality were required to establish whether it is effective in pain management (Rose et al, 2017).

As with many of the treatments for chronic pain, the numbers of animals treated can make it difficult to conduct RCTs. It is also likely acupuncture would not be useful in treating all types of pain, and, as in humans, it may be more appropriate for musculoskeletal and OA pain.

However, multiple anecdotal reports exist of acupuncture improving quality of life of companion animals, so it should not be discounted when treating patients with chronically painful conditions.

Cryotherapy

Cryotherapy is the application of external cooling to a tissue to result in a reduction in temperature. The physiological effects include decreased tissue oedema and microvascular permeability, reduced inflammatory mediators, reduced blood flow due to vasoconstriction, decreased tissue metabolic demand, and increase in the threshold of painful stimuli (Hsu et al, 2019).

Some evidence exists to show it helps reduce analgesic requirements. The temperature required and the time needed to elicit these effects has not been established.

Complications can include nerve palsies (more commonly in superficial nerves) and cutaneous damage, although the risk of the latter should be minimised if adequate insulation is between the skin and cold source.

Therapeutic laser

Low-level laser therapy has become popular in recent years as an aid to pain management. The proposed mechanism of action is by direct and indirect effects on nociceptors, modulation of inflammation and suppression of central sensitisation.

As with many treatment modalities for chronic pain in human and veterinary medicine, the mechanism and effectiveness of treatment is not known. A recent study using low‑level laser therapy in client-owned dogs with OA did seem to show some improved quality of life as reported by owners (Barale et al, 2020).

Conclusion

Acute and chronic pain therapy continues to be a challenge for the general practitioner to treat.

Multimodal analgesic therapy will produce the most consistent results with the fewest side effects, so should be considered for all acute and chronic pain patients.

Not all therapies will be pharmacological, and it is important to consider non-pharmacological therapies in acute and chronic pain.

Clinicians should consider the type of pain the patient is presenting with when deciding on a treatment plan and use some form of scoring system to allow tracking of the patient’s progress. Each patient should be considered individually to establish the best course of treatment for the pet and the owner.