13 Jan 2026

Analgesia: options for treating neuropathic pain in cats and dogs

Matt Gurney BVSc, CertVA, PgCertVBM, DipECVAA, FRCVS explores the medications available to practitioners, including clinical studies of their efficacy, and why usage can require trial and error.

Neuropathic pain is defined as a lesion or dysfunction of the somatosensory system, and can be peripheral or central in origin. Neuropathic pain is typically described as challenging to treat with conventional analgesics (NSAIDs and opioids).

Pharmacotherapy in neuropathic pain was reviewed as a topic by Moore in 2016. Much of the information around analgesic management for neuropathic pain is a result of experience as opposed to definitive prospective clinical studies.

Understanding the pain behaviours associated with neuropathic pain provides us with the ability to judge the efficacy of our treatment options. Features seen with neuropathic pain are allodynia, which is pain in response to a non-noxious stimulus; hyperalgesia, increased pain from a stimulus that normally provokes pain; and dysaesthesia, an unpleasant abnormal sensation, which is spontaneous or evoked.

Discussing the clinical signs with the caregivers allows us to document caregiver-reported outcome measures.

By monitoring these behaviours displayed by the pet, we can ask if these have improved with treatment or if any activities cause an exacerbation in these behaviours.

Work by Ruel et al from 2020 documented a positive benefit to gabapentin in the management of neuropathic pain. This is one of the primary studies in the veterinary literature documenting benefits of using gabapentinoids outside of the literature pertaining to syringomyelia.

Three cases

Three cases of neuropathic pain were reported by Cashmore et al in 2009. These cases are useful, as they describe clinical presentations including treatment attempts in these cases.

The first case detailed by Cashmore et al described a dog with mechanical allodynia of the antebrachium and palmar forepaw. The authors stated that stroking with a pen consistently caused marked agitation in the dog by it pulling its leg away while concurrently vocalising and attempting to bite the examiner. The limb was held in a flexed position at the shoulder and elbow joints, which was thought to be a consequence of the abnormal sensation experienced by the dog.

Electromyography (EMG) suggested a lesion of the median and ulnar nerve roots, and MRI failed to demonstrate a nerve root lesion.

Initially, the dog was treated with amitriptyline 1.4mg/kg by mouth twice a day for one month. Within two weeks, the owners reported no significant change in the dog’s presenting signs and several adverse effects, including altered mentation. The amitriptyline was discontinued and gabapentin 14mg/kg was prescribed. One month later, the lameness had improved, and the mechanical allodynia had resolved. Following three months’ treatment with gabapentin, the lameness had resolved and the dog was using the limb normally.

This is a useful case, as it described the clinical signs seen in this dog. The case reinforces the human perspective regarding the treatment whereby first-line choice may be ineffective or, rather, the beneficial effects are limited due to side effects.

The second case reported was a three-and-a-half-year-old cairn terrier with progressive history of intermittent spontaneous and inducible scratching of the right side of its face. Each episode lasted 20 seconds, during which the episodes could not be stopped by the owner or the clinician. No response was seen to non-steroids or corticosteroids.

Neurological and dermatological examination revealed no further anomalies except mechanical allodynia over the right side of the face, localised to the dermatome supplied by the infraorbital nerve. MRI was unremarkable. A diagnosis of neuropathic pain was presumed.

A one-month trial of gabapentin did not improve clinical signs. One month of amitriptyline produced an immediate and dramatic response until they stopped the treatment, having considered the dog to be cured. Signs recurred within three days and were controlled again by amitriptyline.

The third case in the series was a 12-year-old fox terrier presented for back pain. The owners were unable to touch the dog’s lower back without eliciting severe discomfort, agitation and, sometimes, aggression. Radiographs taken by the referring veterinarian failed to account for clinical signs, and trial treatment with meloxicam failed to show improvement. Upon presentation at the referral centre, diffuse mechanical allodynia was noted over the lumbar region.

Otherwise, neurological, orthopaedic, radiographic and MRI EMG exams were considered normal. A presumptive diagnosis of neuropathic pain with no inciting factor was made. The dog showed a marked improvement in response to amitriptyline, with marked deterioration upon cessation of treatment.

One case report in the literature described the use of amantadine to treat presumed neuropathic pain in a dog. Amantadine was chosen in this case based on the pathophysiology of the condition and the rationale that an NMDA antagonist was required.

The dog in question had previously suffered a road traffic accident and presented with a chronic spinal subluxation. The dog responded positively to the addition of amantadine to NSAID therapy. When the amantadine was stopped, the signs reverted, and control was gained a second time once amantadine was reintroduced.

Syringomyelia is an example of central neuropathic pain and pain that is reported in 35 per cent of dogs with this condition. Pain is more likely in dogs with a wide syrinx and where the syrinx is deviated into the dorsal horn of the spinal cord. One theory suggests that pain is the result of an imbalance of inputs and output from the dorsal horn of the spinal cord, either due to anatomical or neurochemical alterations. Impaired dorsal horn function has been demonstrated in people with syringomyelia; however, the exact mechanism remains unclear. The response to options such as NSAIDs can be variable, and response to gabapentin or pregabalin is more predictable.

In a prospective, randomised, double-masked, cross-over placebo trial with eight dogs, pregabalin was shown to significantly reduce mechanical hyperalgesia, cold hyperalgesia and allodynia compared to a placebo (Sanchis-Mora et al, 2019). This was, however, a very small-scale study.

A further study looking at pregabalin use in syringomyelia set out to assess the efficacy and risk benefit of pregabalin in controlling the scratching episodes in syringomyelia-affected dogs (Thoefner et al, 2020). A total of 12 dogs in a placebo cross-over study were randomised to receive either pregabalin 150mg or placebo for 25 days. The outcome measures were the number of scratching episodes in 10 minutes and a quality of life and benefit assessment.

Regarding the number of scratching episodes, an 84 per cent treatment effect was reported compared to placebo. Quality of life was considered good in 6 out of 11 dogs that completed the study, and quality of life was considered to have improved in 4 out of 11 dogs that completed the study. Adverse effects were polyphagia in 9 out of 12 dogs and ataxia in 9 out of 12 dogs. One dog was withdrawn from the study because of ataxia.

The authors concluded that at a dose of 13mg/kg to 19 mg/kg twice a day, pregabalin improved quality of life. No rescue analgesia was required.

In a study comparing gabapentin to topiramate in client-owned dogs with syringomyelia, the outcome measures used in the study were clinical signs related to quality of life (Plessas et al, 2015). Quality of life was scored using a visual analogue scale (VAS) from zero to 100. Prior to being randomised into either the gabapentin or the topiramate group, all dogs were treated with carprofen for one week. They then received drug A for two weeks, had a washout period of one week, and received drug B for two weeks.

The mean VAS before carprofen was 41.3mm. Seven days after carprofen was 40mm. Two weeks after gabapentin was 30.6mm, and two weeks after topiramate was 33.2mm. The authors concluded no significant difference existed between gabapentin and topiramate. Significant improvement in quality of life was observed after gabapentin compared with baseline.

The most commonly studied analgesics for the treatment of syringomyelia are the gabapentinoids, which leads us to use these as first-line treatment options.

Post-surgical neuropathic pain has been reported in dogs following dental treatment. In a four-year-old male neutered poodle undergoing simple extractions, the dog was noted to scratch the head on one side immediately after dental treatment. This was worse in the morning and worse when the dog was excited.

Upon case examination, it was reported that an infraorbital nerve block was performed by advancing a 27G needle into the infraorbital canal and bupivacaine was injected.

A risk exists of inducing neuropathic pain with advancing a hypodermic needle into the infraorbital canal and this approach is not recommended.

Initial treatment for this dog consisted of pregabalin 3mg/kg twice a day, which was effective. The pregabalin was reduced to 2mg/kg twice a day and that was considered ineffective. Amitriptyline was attempted in this case, and amitriptyline proved to be ineffective.

Further recommendations that could be considered in this case would be the use of NMDA antagonists such as amantadine or memantine to target presumed central sensitisation associated with this case. An alternative would be to repeat a nerve block at a more caudal location to the original nerve injury.

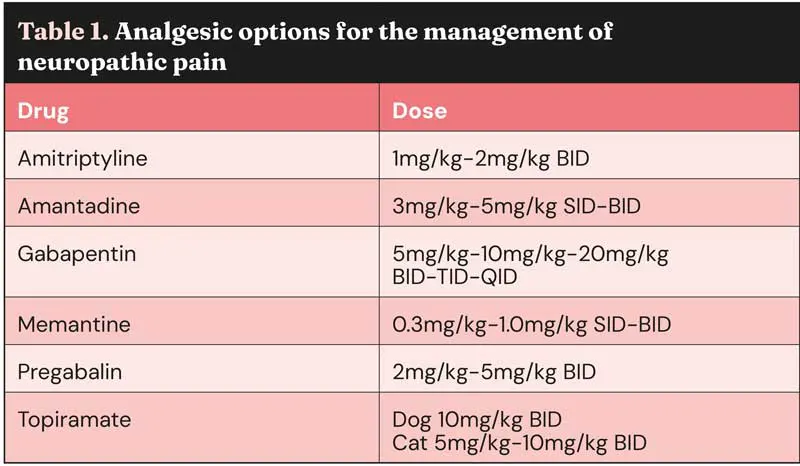

The mechanisms and multimodal management of neuropathic pain in cats has been usefully reviewed by Clare Rusbridge in a Journal of Feline Medicine and Surgery article from 2024. Rather than attempt to summarise this extensive work here, the reader is referred to the open access paper. Table 1 includes analgesic options for the management of neuropathic pain.

Analgesic notes

Amitriptyline

The mechanism of action of amitriptyline is a sodium channel blocker. It makes sense to use this in neuropathic pain due to peripheral neuronal hyperexcitability, which is a feature of nerve damage and can result in up-regulation of sodium channels.

Topiramate

The mechanism of action of topiramate in neuropathic pain is thought to be by sodium channel blockade, and rationale for inclusion is similar to that of amitriptyline.

Gabapentinoids

The mechanism of action of gabapentinoid analgesia is a result of the gabapentinoid binding to the alpha-2 delta subunit of the voltage-gated calcium channel in the dorsal root ganglion, which is involved in the maintenance of mechanical hypersensitivity.

A second mechanism of action involves descending noradrenergic control, which is impaired in chronic pain. The use of gabapentinoids activates the inhibitory system, increasing activity of noradrenergic neurones located in the locus coeruleus.

Gabapentin and pregabalin activate the locus coeruleus; they inhibit GABA, this increases glutamate, resulting in an increase in spinal noradrenaline. Noradrenaline binds to alpha-2 agonist receptors to produce analgesia at a spinal level.

NMDA antagonists

Amantadine and memantine are NMDA antagonists. Central sensitisation is a feature of neuropathic pain and the NMDA receptor is one of the key receptors involved.

Peripheral nerve activity produces constant input to the dorsal horn of the spinal cord and drives central sensitisation. The inclusion of NMDA antagonists is recommended where central sensitisation is suspected.

Conclusion

Effective treatment of neuropathic pain is a challenge. Even when the diagnosis of neuropathic pain is certain, we often see a variability in patient response to analgesics.

As seen in the cases discussed, it is not always easy to say which analgesic to start with, and these cases can involve a degree of trial and error.

- Use of some of the drugs in this article is under the veterinary medicine cascade.

- This article appeared in Vet Times (2026), Volume 56, Issue 2, Pages 6-9.

Matt Gurney is a specialist in anaesthesia and pain management. Matt sees chronic pain cases at Eastcott Referrals in Swindon and at Pawra, a canine wellness centre in London. Matt is co-founder of Zero Pain Philosophy, an educational resource for vet professionals.

References

- Cashmore RG, Harcourt-Brown TR, Freeman PM, Jeffery ND and Granger N (2009). Clinical diagnosis and treatment of suspected neuropathic pain in three dogs, Australian Veterinary Journal 87(1): 45-50.

- Moore SA (2016). Managing neuropathic pain in dogs, Frontiers in Veterinary Science 3: 12.

- Plessas IN, Volk HA, Rusbridge C, Vanhaesebrouck AE and Jeffery ND (2015). Comparison of gabapentin versus topiramate on clinically affected dogs with Chiari-like malformation and syringomyelia, Veterinary Record 177(11): 288.

- Ruel HLM, Watanabe R, Evangelista MC, Beauchamp G, Auger J-P, Segura M and Steagall PV (2020). Pain burden, sensory profile and inflammatory cytokines of dogs with naturally-occurring neuropathic pain treated with gabapentin alone or with meloxicam, Plos One 15(11): e0237121.

- Sanchis-Mora S, Chang YM, Abeyesinghe SM, Fisher A, Upton N, Volk HA and Pelligand L (2019). Pregabalin for the treatment of syringomyelia-associated neuropathic pain in dogs: A randomised, placebo-controlled, double-masked clinical trial, Veterinary Journal 250: 55-62.

- Thoefner MS, Skovgaard LT, McEvoy FJ, Berendt M and Bjerrum OJ (2020). Pregabalin alleviates clinical signs of syringomyelia-related central neuropathic pain in Cavalier King Charles Spaniel dogs: a randomized controlled trial, Veterinary Anaesthesia and Analgesia 47(2): 238-248.