23 May 2023

Victoria Robinson and Matt McHale provide a case-by-case guide to treating this frustrating skin condition, which requires lifelong management.

Image: © Happy monkey / Adobe Stock

Canine atopic dermatitis (CAD) is a common, chronic inflammatory and pruritic skin condition.

Similar to human eczema, affected individuals are often genetically predisposed to developing disease, necessitating lifelong management to prevent inflammation, itch and secondary infection.

CAD is a multifactorial condition that requires a holistic approach to manage (Saridomichelakis and Olivry, 2016).

Factors that may affect dogs with atopic dermatitis include:

Diagnosis is made based on a thorough clinical history, clinical exam and exclusion of other skin diseases.

Signalment can be of use in prioritising a differential diagnosis of atopic dermatitis, and cases are often a young (six months to three years old) dog.

The following breeds are over-represented:

Although aural and pedal pruritus is thought to be a classic presentation of CAD, breed variance exists – especially in the WHWT with dorsal pruritus, and in the Shar Pei, with generalised body and hindlimb pruritus (Hensel et al, 2015). Body maps depict common areas of pruritus in specific breeds; however, exceptions can be noted – especially with secondary bacterial folliculitis and/or ectoparasite burden, including demodicosis (Wilhem et al, 2011). The reader is directed towards the following article for detailed discussion on workup (Hensel et al, 2015).

A thorough clinical history is crucial in CAD – especially with the chronicity and insidious onset in some patients.

Open questions are vital to ensure the client is not biased in their response. It is also useful in determining treatment regime compliance, as owners with structured management can usually recall product name and frequency of use.

Common pitfalls are often related to closed or passive questioning, such as:

Using questions that begin with what, when, why, who, where, and how can help to build a bigger and more accurate picture of the clinical case, such as:

History taking can be helpful in refining a differential diagnosis list, and identifying patterns or flare factors in CAD. It is important to ascertain if any seasonality with disease exists; for example, if only summer itch is present, then food is unlikely to be a factor and elimination diet unnecessary.

A thorough clinical examination is vital in all cases and commonly overlooked areas may yield important information – these include cutaneous marginal pouches, which can often hide Neotrombicula autumnalis mites in the months of August to October.

Lip folds can be of particular importance in cases of recurrent otitis, chronic cheilitis and facial pruritus. The claw folds and palmar/plantar aspects of the paws should be inspected closely, and cytology from these two areas can differ, which may prompt separate treatments.

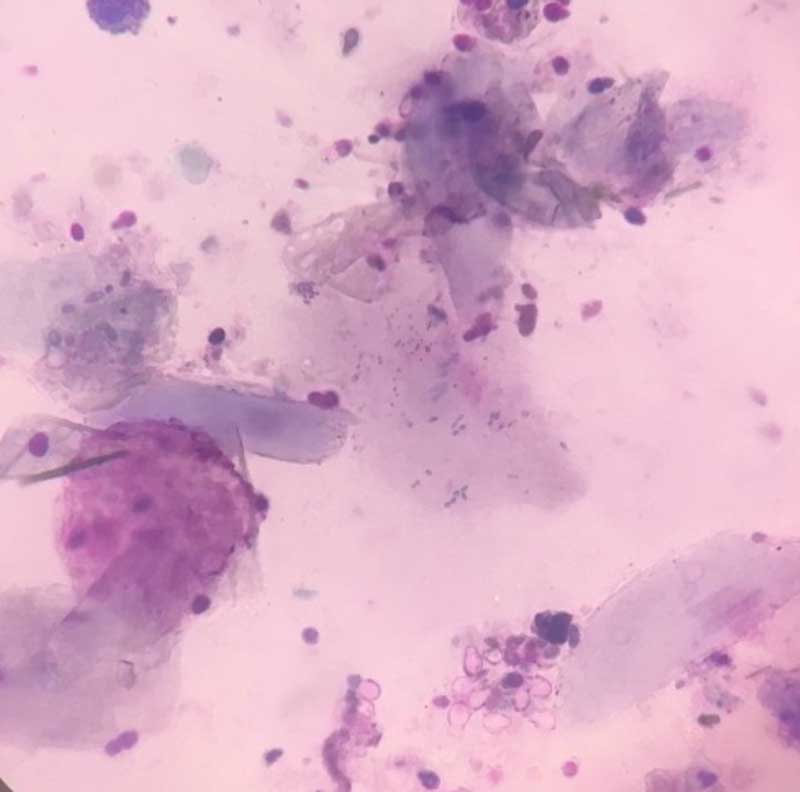

Cytology findings and interpretation will be covered in the following cases.

As a note, cytology from the concave pinnae may differ from the ear canals, despite close proximity.

Once the patient has been treated for any microbial overgrowth with or without ectoparasite infestation, then baseline itch can be determined; for example, a patient with bacterial pyoderma and an itch score of 8 out of 10 (Hill et al, 2007) reduces to 4 out of 10 once secondary infection has resolved.

A thorough guide to induction/reactive therapy can be found here.

History of diarrhoea, flatulence and increased frequency of defecation can indicate food as a factor in atopic dermatitis (Mueller and Olivry, 2018).

Common pitfalls during a diet trial include treats, dental hygiene sticks, supplements and flavoured medications (including oral flea treatment). Client handouts and regular communication (phone, email or text, depending on practice management system) can improve compliance.

Anti-itch medication should be tapered around four weeks into an elimination diet trial for accurate assessment of food as a factor in itch (Favrot et al, 2019; Fischer et al, 2021).

For further information, read this article.

Intradermal allergen testing and allergen IgE serology should only be performed as a guide to allergen-specific immunotherapy.

These are not a diagnostic tool, as unaffected animals can show positive results. Intradermal allergen testing should be performed during or shortly after the period of increased itch, in an animal with a seasonal flare (Saridomichelakis and Olivry, 2016).

Test results should be interpreted alongside clinical history. If the patient has clear summer itch, but only house dust mite sensitisation is evident on testing, then additional investigations or questions should be asked before formulating allergen-specific immunotherapy.

Proactive maintenance therapy is vital to long-term management of patients and treatment should be tailored to each individual patient. The authors will discuss some cases in which different management strategies are more appropriate.

A guide to maintenance therapy can be found here.

A full case workup might not be necessary in cases where dogs exhibit only mild and/or short seasonal flares, such as tree pollen. It may be possible to control itch with anti-pruritic medication used pre-emptively with the aid of online pollen counts and calendars.

If itch is moderate to severe and either perennial (with food ruled out) or longer-lasting seasonal flares, investigation into environmental allergens is warranted.

These cases often benefit from allergen-specific immunotherapy, with maintenance medications including topical antiseptics, topical glucocorticoids or oclacitinib/lokivetmab.

Monitoring for signs of erythema, lichenification, alopecia and saliva staining is important. This may indicate a need to alter therapies or increase the frequency of use.

Cytology should be used to check for secondary microbial overgrowth.

Ectoparasite infestations should always be ruled out as a cause of increased pruritus in well-controlled atopic patients.

The patient presents with sudden onset right forelimb lameness following a long walk in the countryside. Summer pedal pruritus was reported in history.

Other than a body condition score of seven out of nine and splayed foot conformation, general physical examination is unremarkable.

Examination of the paws shows weight bearing on haired skin, new pad formation, deep pockets and moderate brown exudate on the palmar surface. An interdigital furuncle is evident on the dorsal surface between digits three and four of the right fore (Figures 1 and 2).

Cytology is easily performed, cheap, non-invasive and allows assessment of microbial overgrowth/infection as a factor in pedal pruritus.

The furuncle can be ruptured via 25G orange needle for cytology, and a sample collected simultaneously for culture and susceptibility testing, if required. Trichography is particularly useful for Demodex, as skin scrapes are rarely tolerated on the paws.

Radiographs can be considered if abnormalities are present on orthopaedic examination or concerns exist of a foreign body. Surgical exploration and biopsy are not indicated in chronic pododermatitis with interdigital furunculosis (CPIF) that responds as expected to therapy.

Biopsies may be indicated where a focal lesion is present and neoplasia is a differential. Tissue culture of biopsies should be considered if systemic antibiosis is necessary.

Cytology and trichogram were performed, showing Malassezia and cocci overgrowth, and no evidence of ectoparasites on trichography (Figure 3).

A previously stable CAD (environment) patient presents with sudden, severe pedal pruritus. It is up to date with fluralaner ectoparasite prevention and was previously well maintained on oclacitinib at approximately 0.5mg/kg once daily.

Figure 4 shows findings on clinical examination.

The patient presents with severe head shaking and aural pruritus. In this type of case, determining the chronicity, speed of onset and if this is the first time it has happened is important.

The owner reports the onset was acute and occurred after a day in the forest/swimming, and no other pruritus is present (paw licking, scooting and so forth).

On brief examination, inflammation of the ear canals is present and waxy discharge is visible in one of the ears.

Otoscopic examination of the other ear is not tolerated.

Dermatological conditions can be difficult to manage, both in terms of clinical outcomes and client communications.

Explaining that CAD is very similar to human eczema and requires lifelong management often helps to manage client expectations, and can allay some frustration down the line. Long-term management is essential to prevent inflammation, itch and secondary microbial overgrowth/infections.

Often, these patients and clients will be coming to the practice for 10 to 15 years, and fostering good rapport with the client is vital for good clinical outcomes.

Taking a proactive approach to skin disease will often decrease costs to the client and increase the patient’s quality of life. A reactive approach leads to higher peaks in itch, more severe lesions and, in the case of otitis, this may also lead to surgical management becoming necessary.

Early referral of cases that do not respond accordingly to therapy or present unusually can increase patient welfare, reduce costs and improve clinical outcomes. Remember to consider the causes of an unexpected flare in CAD patients often associated with the primary condition and/or secondary infections; however, ectoparasites, endocrinopathies, neoplasia and foreign bodies should be ruled out if suspicion exists from the history and clinical examination.

Matt McHale

Job TitleVictoria Robinson

Job Title