4 Mar 2025

Avian influenza in felines – is this a cause for concern?

Caroline Allen BA, VetMB, CertSAM, MRCVS and Alison Richards BVSc, MRCVS discuss the risks this disease poses to cats and other mammalian species in the UK, and steps animal carers can take to reduce the dangers.

Image: BillionPhotos.com / Adobe Stock

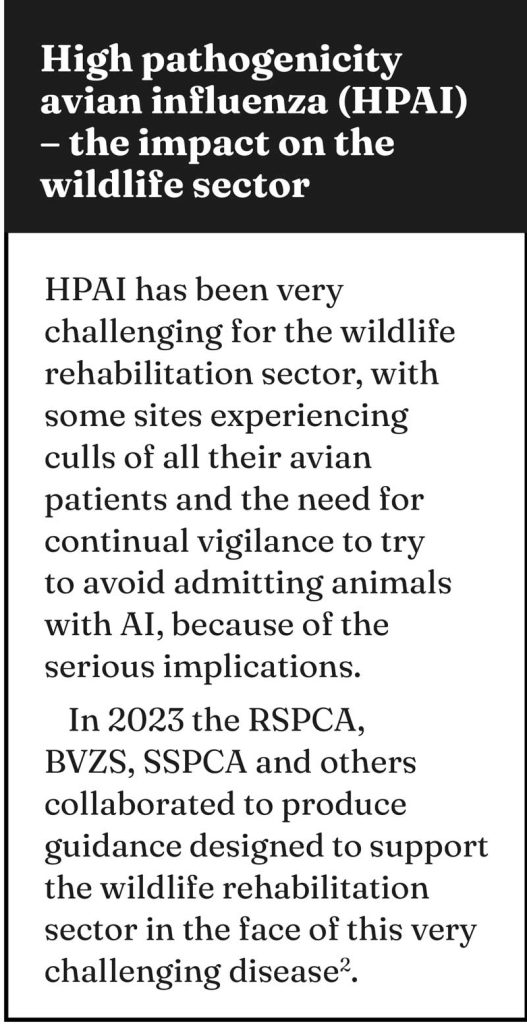

It would not have escaped the attention of veterinary teams that, over the past few years, the health and welfare of many avian species has been significantly impacted by high pathogenicity avian influenza (HPAI).

In wild birds, we have seen high mortality in sea bird colonies and outbreaks in some areas resulting in high numbers of dead and dying waterfowl.

The poultry industry has been impacted significantly with multiple sites affected, resulting in culling of the flock and restrictions on animal movements.

Housing orders, while necessary for biosecurity, also present a significant welfare concern across the sector.

The Government’s website provides up to date information on this disease at bit.ly/4khW9vK

The risks in relation to birds are very much still present; however, colleagues will probably be aware of the increasing focus on mammalian cases.

The fact that HPAI can infect mammals has been known for some years1, with an increasing number of species being shown to be susceptible and with varying degrees of pathogenicity.

This article focuses on infection in cats, a species that is known to be highly susceptible. The RSPCA and Cats Protection are collaborating to share our understanding of what HPAI may mean for our organisations, and other animal shelters across the UK. It considers the risks to cats based in the UK and the steps animal carers can take to reduce this risk.

RSPCA and Cats Protection sit as members of the APHA’s Small Animal Expert Group, part of the Surveillance Intelligence Unit, and we heard from professor Ashley Banyard, an HPAI disease consultant working for APHA.

Prof Banyard said: “HPAI has spilled over into mammalian species in recent years due to the high levels of mortality in wild bird populations and a resultant increase in infection pressure in the environment.

“This has been seen globally with numerous terrestrial and marine mammalian species becoming infected and succumbing to disease, with infection likely being the result of scavenging behaviours.

“Globally, infection of wild and captive felids has also been seen. Most strikingly, in the US where domestic cats have consumed raw milk from infected dairy cattle, or have been infected through raw food feeding practices, mortality events have been seen.

“Further, infection in captive zoological collections of big cats has also been reported, again most likely being infected through provision of infected meat.”

Further concerns have been raised with the emergence of a new genotype of H5N1 HPAI in cattle in Nevada.

Prof Banyard said: “This latest emergence is concerning, as it has further demonstrated the risk of infection with non-avian hosts.

“Time will tell how this latest detection will impact on risk factors and in particular zoonotic risk and we are monitoring the international situation closely.”

The take-home messages were that while HPAI is a complicated disease, with multiple different virus clades, subtypes and genotypes circulating around the world, a lot of monitoring of these different viruses is taking place, and at the time of writing APHA rates the risk to cats in the UK as very low. However, it is sensible for vets to be aware of the risk factors and possible clinical signs and, crucially, remember that HPAI is a notifiable disease in all species.

More information on reporting can be found at bit.ly/4kf86SM

How might cats get infected?

Across the globe, a small number of domestic cats have been found to be infected with avian influenza, and a number of different routes and risk factors must be made aware of. Exposure to wild birds, infected by the virus, is a possible route to transmission.

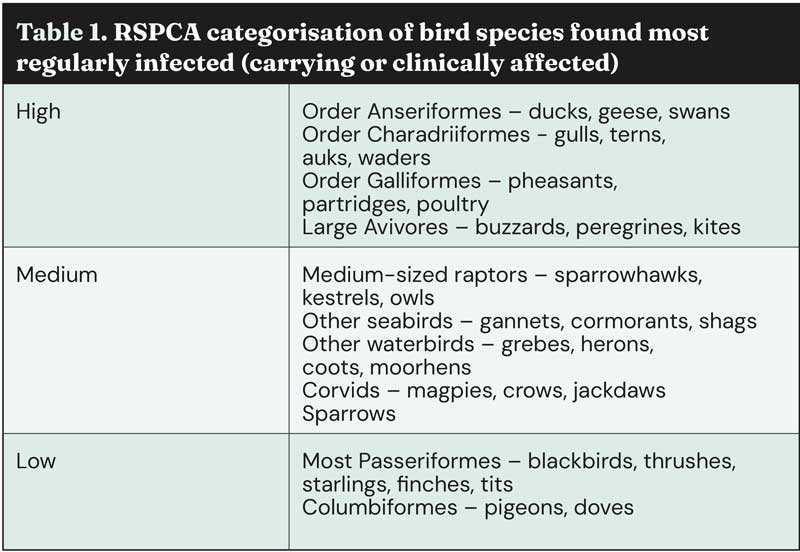

Gulls, raptors and waterfowl make up the majority of wild avian species that have been infected by HPAI in the UK, with the smaller bird species which cats are likely to predate only very rarely being found to be positive for infection.

However, in areas where significant numbers of birds have died and pets are able to access the carcases, this may pose a potential risk, although much higher levels of bird mortality reported in previous years did not lead to diagnoses in cats (Table 1).

A number of cases have also been reported where cats have been infected where the source is thought to be ingestion of infected and uncooked poultry meat. An outbreak in shelter cats in South Korea was determined to be related to contaminated pet food had been improperly sterilised3.

The source of an outbreak in Poland of domestic cats in various cities could not be elucidated4. Some suspected raw food-linked cases have occurred in the US, where investigations are ongoing, but in a case in Oregon, the virus isolated from the cat and the virus isolated from the food matched, resulting in a voluntary recall5.

More recently, a large number of cows in the US have been diagnosed with H5N16. Discussion of these cases is beyond the scope of this article.

What has been noticeable is that a number of HPAI-related deaths have occurred in cats living in close proximity to the infected dairy cows. This is believed to be due to the ingestion of infected milk and colostrum, and is the first evidence of inter-species mammalian spread.

However, this genotype of virus is not currently found in the UK or Europe, and based on the risk assessment for likely pathways for introduction to the UK, it is considered a very low risk at most2.

What are the symptoms in cats?

- Neurological signs – tremors, seizures, ataxia, circling, blindness.

- Unexplained death.

- Severe depression.

- Clinical signs of respiratory disease that is unusual or severe (for example, advanced pneumonia).

What does this mean for cat carers in the UK?

Given the close relationship between cats and their owners, these developments may cause concern for cat carers, who may turn to vets for advice and reassurance. UK Government guidance can be found at bit.ly/3D8fdvE and focuses on the following:

- Keep pets away from wild birds – this includes feathers and droppings so ensuring feed and water bowls cannot get contaminated. If an outbreak of bird flu or cases in wild birds occurs in the area, then owners should remain aware and monitor for clinical signs.

- Do not feed raw poultry meat or any uncooked wild bird meat.

Guidance for shelters and practices

Be aware of risk factors and take a good history where it is possible to do so. Consider the lifestyle and behaviour of the cat (for example, free roaming, a hunter) and the likelihood of exposure to infected wild birds in a confirmed outbreak area, as well as other possible diet sources such as raw poultry meat.

Note that the highest risk birds are not those species that we would normally expect cats to predate, and we do not recommend keeping cats indoors due to HPAI risk. Be aware and observant of the signs of infection with avian influenza type A in cats.

An unusually high incidence of severe feline respiratory disease may be a cause for concern, noting that cat flu is a common disease in the shelter setting. Shelter teams should alert their attending veterinary surgeon immediately, so that reporting can take place.

Appropriate biosecurity should already be in place for cats showing these symptoms, as many differentials are also infectious.

It would be timely to remind colleagues of the importance of good PPE, hand hygiene and biosecurity – especially for staff, volunteers and vets working in shelters. It is really important for vets to lead by example when visiting the shelter.

Suspect cases must be reported and must be handled minimally with appropriate PPE.

Isolate cats that exhibit newly developed neurologic signs or neurologic signs with an unknown history.

Avoid raw pet food. Raw pet food is made from both domestic and imported meat, or products of animal origin which are fit for human consumption, but where a “kill step” is not used, to reduce the presence of pathogens.

However, infected untreated poultry meat being fed to cats is a recognised route of infection, so should not be fed.

Raw meat does pose other health risks to the cats being fed it and those caring for the cats, so would not be appropriate in a shelter environment or where vulnerable people are in contact with the cats or the food.

If you keep birds in a shelter environment, these should be kept physically separate from other species, ideally in a different airspace. They should be in a different airspace to cats and other predator species for welfare reasons.

Biosecurity protocols should be clearly set out; follow guidance produced by the BVZS7.

Summary

The likelihood of avian influenza infecting cats remains very low in the UK.

However, it is important that vets are aware of the risk factors and the symptoms of this notifiable disease, while maintaining a proportionate response and ensuring that cat owners are not unduly concerned.

The possible presence of HPAI does not negate the responsibility of vets to provide emergency care for bird species, as per RCVS guidelines – see bit.ly/4gWrIYX for the college’s recent reminder of this requirement – and practices should have appropriate biosecurity, PPE and other protocols in place.

References

- Kaplan BS and Webby RJ (2013). The avian and mammalian host range of highly pathogenic avian H5N1 influenza, Virus Res 178(1): 3-11.

- Defra (2023). Avian influenza (bird flu) in dairy cattle in Great Britain, GOV.UK, bit.ly/3EZ0m7e

- Kim Y, Fournié G, Métras R et al (2023). Lessons for cross-species viral transmission surveillance from highly pathogenic avian influenza Korean cat shelter outbreaks, Nat Commun 14(1): 6,958.

- Rabalski L, Milewska A, Pohlmann A et al (2023). Emergence and potential transmission route of avian influenza A (H5N1) virus in domestic cats in Poland, Euro Surveill 28(31): 2300390.

- American Veterinary Medical Association News (2025). Cat deaths linked to bird flu-contaminated raw pet food, sparking voluntary recall, bit.ly/3D8gkeO

- Burrough ER, Magstadt DR, Petersen B et al (2024). Highly pathogenic avian influenza A(H5N1) clade 2.3.4.4b virus infection in domestic dairy cattle and cats, United States, Emerg Infect Dis 30(7): 1,335-1,343.

- BVZS et al (2023). Guidance on the management of wildlife rehabilitation centres in an avian influenza outbreak, BVZS.CO.UK, bit.ly/3ESAPfS