4 Jan 2022

Mike Davies discusses risk factors for some common age-related diseases in cats and dogs, as well as the importance of screening.

Image © Mrdidg / Pixabay

“An ounce of prevention is worth a pound of cure” (de Bracton, 1240) and “prevention is better than cure” (Desiderius Erasmus, 1466 to 1536) are well known quotations that are particularly appropriate when considering the management of elderly patients.

Maintenance of good health and avoidance of exposure to risk factors are important objectives for veterinary clinicians, but applying basic preventive medicine principles requires time and owner compliance.

Sadly, the evidence is that owner compliance with veterinary recommendations to screen apparently healthy elderly animals is poor.

In this paper, the author shall discuss risk factors for some common age-related diseases and why geriatric screening is so important to identify problems early, so that risks can be minimised and interventions can be started early to maximise the likelihood of successful disease management.

Some age-related diseases in cats and dogs, as well as known risk factors, are listed in Table 1.

| Table 1. Known risk factors for some age-related diseases in cats and dogs | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Age-related diseases in cats | Age-related diseases in dogs | Recognised risk factors | Avoidance of risk factors |

| Cancer | Cancer | • Obesity • Exposure to topical insecticides |

• Avoid obesity • Avoid exposure to topical insecticides |

| Cardiac disease: endocardiosis | • Breed, connective tissue disorders • Infection • Poor dental hygiene |

Breed away from affected lines • Dental prophylaxis |

|

| Constipation | * | Dehydration | Maintain hydration status |

| Dental disease – periodontal disease/infection | Dental disease – periodontal disease/infection | Accumulation of plaque and tartar | Dental prophylaxis |

| Obesity | Obesity | • Genetic inheritance (for example, Labrador retrievers) • Excessive calorie intake • Lack of exercise |

• Breed away from affected genetic lines • Control calorie intake to maintain optimum body condition score • Maintain regular exercise |

| Endocrine disease: a) Cushing’s (hyperadrenocorticism; uncommon) b) Diabetes mellitus type-two non-insulin-dependent c) Hyperthyroidism d) Acromegaly |

a) Cushing’s syndrome (hyperadrenocorticism) b) Diabetes mellitus – type-one Insulin-dependent c) Hypothyroidism |

a) Tumours; long-term therapy with corticosteroids b) In cats secondary to obesity c) Hyper – high iodine intake d) No known risk factors |

• Avoid long-term corticosteroid administration • Avoid obesity, weight loss if overweight • Avoid high iodine intake • Avoid feeding raw food containing thyroid tissue |

| “Feline triad syndrome“, but may occur individually as well a) IBD b) Pancreatitis c) Cholangitis/cholangiohepatitis |

a) IBD b) Pancreatitis |

• Feline triad syndrome: autoimmune disease • Acute pancreatitis can be induced by high fat consumption |

Avoid feeding high fat foods |

| Hepatic lipidosis (fatty liver) | Hepatic lipidosis (fatty liver) | • Obesity • Diabetes mellitus |

Maintain optimum bodyweight and condition |

| OA | OA | • Trauma, laxity in joints • Excessive food intake |

• Avoid excessively vigorous exercise • Dogs: reduce food intake by 25% and maintain a BCS of 4.6/9 |

| Prostate disease | Prostate disease (hyperplasia) | Entire male condition | Castration or hormone treatment |

| Renal disease – chronic (CKD) | Renal disease – chronic (CKD) | Obesity, diabetes mellitus, hypertension, infections | • Avoid obesity, manage diabetes and hypertension • Dental prophylaxis • Therapeutic diets |

| Vestibular syndrome | * | Otitis externa | Maintain a clean external auditory canal |

| IBD = inflammatory bowel disease; BCS = body condition score; CKD = chronic kidney disease; * = not common in the species. | |||

Obesity has been associated with an increased risk of cancer – for example, bladder cancer in dogs (Glickman, 1989) so maintenance of optimum bodyweight and condition score should be a priority throughout life. Topical insecticide exposure was also linked to bladder cancer in the same study.

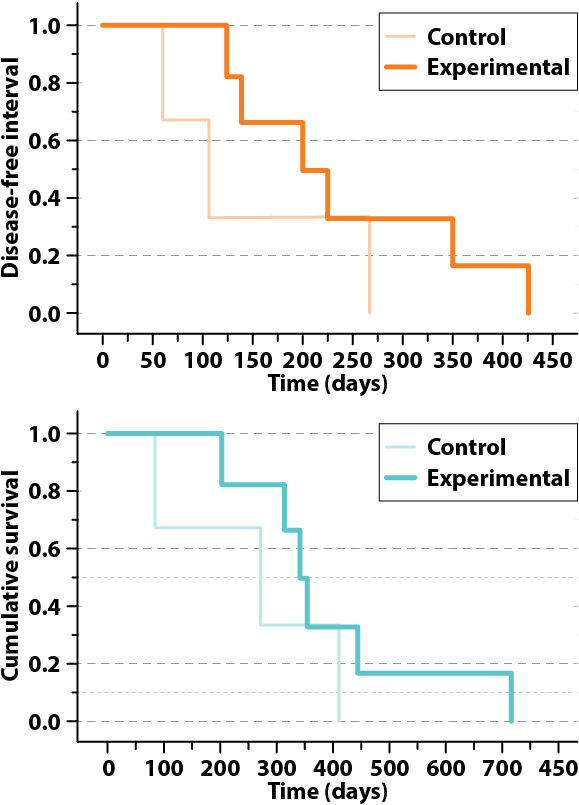

For some forms of cancer (for example, canine lymphoma) high carbohydrate intake is considered a risk factor as the tumour utilises carbs for energy supply and control of dietary intake (in the case of lymphoma restricted carbohydrates, increased protein, omega-3 fatty acids and supplemental arginine) may delay progression, increase remission periods and prolong survival time (Figure 1).

Age-related OA (Figure 2) results because of increased laxity of supporting soft tissue structures including joint capsule, ligaments and tendons. This laxity allows excessive movement across the joint, putting abnormal biomechanical forces on the cartilage, capsule and periosteum around the joint margins resulting in new bone (osteophyte) formation.

Abnormal forces and excessive range of movement causes trauma and intra-articular release of pro-inflammatory factors, which damage cartilage and other joint tissues. Eventually, cartilage erosion results in exposure of subchondral bone, pain and further inflammation. New bone deposition around the joint results in restricted range of movement with crepitus and, in some cases, even ankylosis.

Use of anti-inflammatory and analgesic medicines is widespread, but in fact there is evidence that restricting food intake throughout life can prevent the expression of OA – even in high-risk breeds such as the Labrador retriever.

In a controlled lifetime study (Smith, 2006) 24/48 Labrador retrievers fed 25 per cent less food than their littermates did not develop clinical OA over the duration of their lives (12 to 13 years). Both groups of dogs had their hips radiographed every 12 months and in the diet-restricted group one of the first radiographic signs of OA did not occur until a mean age of 12 years, whereas it occurred at a mean age of 6 years in the ad lib fed group.

It should be noted that the earlier development of OA was not due to obesity as, although body condition score (1 to 9 point) during the period from 6 to 12 years of age was significantly (P<0.01) higher for dogs in the controlled-feeding group (6.7 ± 0.19) than for dogs in the restricted-feeding group (4.6 ± 0.19), those in the ad lib fed group were overweight not obese.

The primary cause of chronic kidney disease (CKD) in dogs and cats is unknown, although increasing interest exists in the potential role for mineral accumulation (for example, arsenic, iron) and free radical damage.

Known causes include bacterial infections, which may originate from dental infection. Dental disease is so prevalent in ageing cats and dogs that dental prophylaxis is an important preventive measure.

The only treatment modalities that have been shown to delay progression and prolong lifespan in veterinary patients with advancing CKD are dietary management (Roudebush, 2010), calcitriol and possibly dialysis (International Renal Interest Society, 2021). Only marginal clinical improvements can be achieved using erythropoietin and other medical interventions.

The use of therapeutic diets has been shown to delay progression of CKD and prolong life. Especially important is the need to control protein and phosphorus intake, and other nutritional manipulations that may be beneficial include increased vitamin B intake, omega-3 fatty acid supplementation and increased antioxidant provision (Figure 3).

Idiopathic constipation can often be prevented by manipulation of intraluminal fibre content using a high-fibre therapeutic diet. Another risk factor is dehydration, so hydration status needs to be maintained by ensuring adequate water intake through drinking or in wet foods (Figure 4).

In dogs, diabetes mellitus is usually type-one insulin-dependent and it is caused by autoimmune damage to the insulin-producing Islets of Langerhans in the pancreas. This cannot be prevented until the underlying cause has been determined. However, cats develop type-two non-insulin dependent diabetes mellitus secondary to insulin-resistance in association with obesity.

Diabetes mellitus in cats can be prevented by maintaining optimum body condition score, avoiding obesity, and the condition can be treated in most patients by achieving adequate weight loss.

Hyperthyroidism due to thyroid adenoma is common in middle-age to elderly cats. In most cases, excessive iodine intake does not appear to be a cause; however, high iodine can result in hyperthyroidism and so high intake should be avoided. Iatrogenic hyperthyroidism has been reported in dogs fed raw foods containing thyroid tissue (Köhler et al, 2012).

In addition to surgical and medical interventions, including radiotherapy, the hyperthyroid state in cats can be managed very well by the feeding of an iodine-restricted diet (Hill’s Prescription Diet Y/D) as long as the cat gets no other food supply.

Quality of life is a more important objective than increasing lifespan per se; however, lifespan was increased by about 18 months in a lifetime study in Labrador retrievers that had their food restricted by 25 per cent compared to littermates (Kealy et al, 2002).

Unfortunately, pet owners are often unable to recognise when their companion is seriously ill (Davies, 2011), especially if a disease has been slow in onset. Screening is an opportunity to pick up those cases, to start interventions early, and to identify and remove risk factors.

The author had one lady bring her dog in for a geriatric screen and it was cyanotic, with air hunger and abdominal distension, and could hardly walk – she thought she had slowed down and gained weight because of old age, but in fact her dog was in heart failure. In another similar case the dog had a massive intrabdominal mass.

Published studies have clearly demonstrated the benefits of performing screening examinations on apparently healthy elderly pets and it is disappointing that compliance with veterinary recommendations to do screening is low – at about 34 per cent (American Animal Hospital Association, 2003).

Early detection of disease increases the likelihood of successful management, and for some conditions, such as cancer, can mean the difference between achieving a cure, or just ameliorating the condition and improving quality of life. It needs to be stressed that a geriatric screen does not simply mean a blood screen – indeed, the most important elements are a detailed history and physical examination.

When screening dogs older than seven years of age, one can expect to find more than seven major disorders, including pain (25 per cent) – mainly musculoskeletal, but also abdominal, dental disease and neoplasia (Davies, 2012).

In the author’s clinics a urinalysis (chemical dip stick, visual appraisal and specific gravity by refractometer) is always done as it is non-invasive, inexpensive and provides a lot of useful, sometimes unexpected, information.

For example, the author has seen several asymptomatic cats that had persistent haematuria, which on follow-up imaging turned out to be due to bladder cancer involving the main body of the bladder wall, but not yet invading the trigome. Radical excisional surgery was able to prolong the symptom-free period for many months – in one cat for more than 12 months before it was euthanised for other reasons. Other findings in asymptomatic animals are proteinuria (13 per cent) and urinary tract infections (4 per cent; Willems et al, 2017).

Screening will often identify haematological or biochemical results outside the normal reference range, and so it is a rewarding thing to do.

However, as this is an invasive procedure the author only performs blood analysis if it is indicated from the history or physical examination, or before exposure to additional risks, such as the introduction of medications with a narrow therapeutic index (it is a data sheet recommendation prior to the use of NSAIDs and angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors) or as a pre-anaesthetic screen, which has been shown to be a valid procedure even though the number of abnormalities that are found that would not be indicated from a good history or examination is low; less than one per cent (Joubert, 2007; Alef et al, 2008; Apfelbaum et al 2012; Davies and Kawaguchi, 2014).

It is important to obtain a detailed clinical history and to carry out a detailed physical examination to identify risk factors for age-related diseases. It is best practice to screen asymptomatic elderly pets to identify disorders that have not been noticed by owners.

Screening is particularly important prior to the administration of medicines with a narrow therapeutic index and prior to general anaesthesia or surgery.