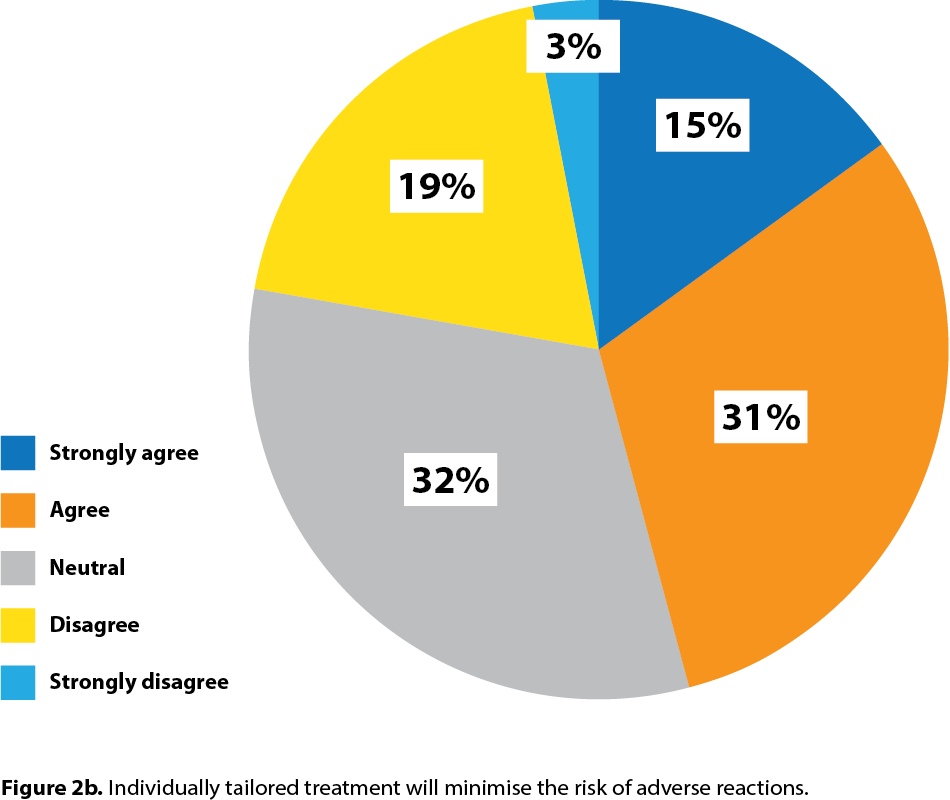

As shown in Figure 1a, 81% (n = 97) of participants agreed (31% [n = 37] strongly agreed) that “Individually tailored parasite treatment is the best compromise to minimise environmental contamination while still preventing parasite infestation”.

21 Jun 2023

Amy Bagster and Hany Elsheikha, in the first of a two-part article, share insights into the attitude of UK small animal vets towards this approach.

Background: The concept of tailoring parasite treatment for individual animals according to their circumstances and specific risk factors – the so‑called “risk‑based parasite control approach” – has gained a momentum in recent years. Key advisory and regulatory bodies have provided position statements in favour of the use of risk‑based parasite control.

Despite this enthusiasm, challenges exist to the integration of this new treatment model into clinical practice. Insufficient evidence exists to support – or doubt – the efficacy of risk‑based approach as many questions remain unanswered, and the factors affecting animal susceptibility to infection, treatment responses and adherence to treatments are not fully defined. This is further complicated by the dynamic nature of parasite risk.

Methods: This cross-sectional study used a survey to investigate perception of small animal clinicians towards implementing a risk assessment-based approach to parasite control.

Results: Of the 119 participants who completed the survey, 81% (n = 97) agreed that individually tailored parasite treatment is the best compromise to minimise environmental contamination while still preventing parasite infestation.

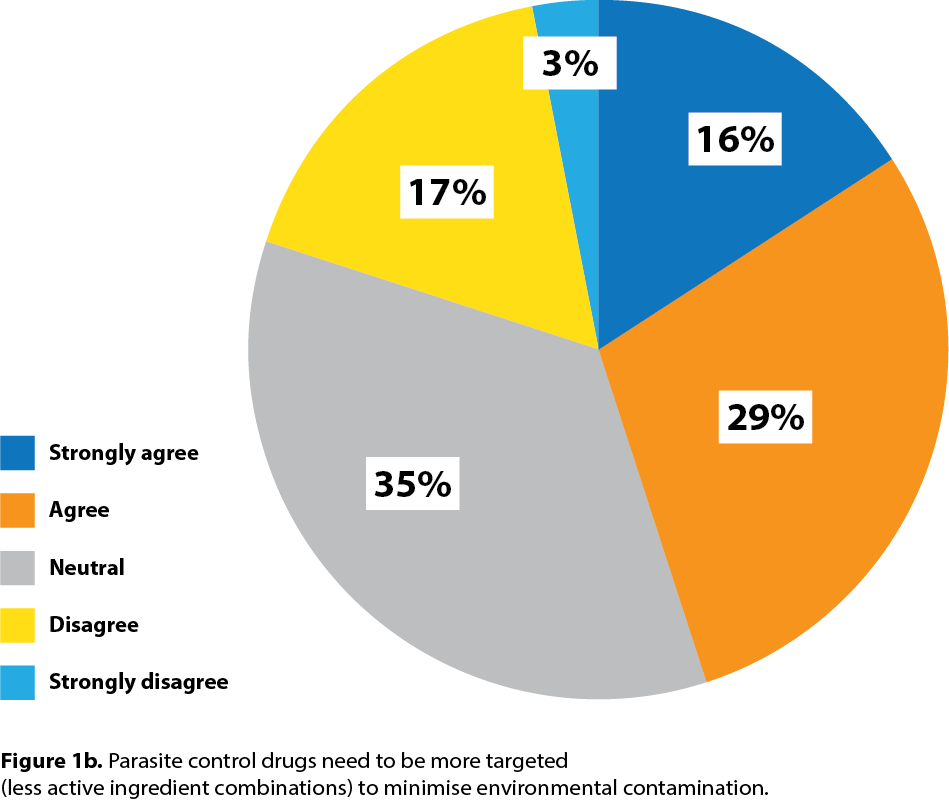

A total of 86.5% (n = 103) would like to see more research conducted into veterinary medicine‑related parasiticide products in the environment, including levels, extent of harm and pathways into it.

The results also showed a need for longer consult times, and more resources to assist clinicians in decision making on individually tailored parasite control would be helpful. Limited autonomy was a major limiting factor for adopting risk-based parasite control for many veterinarians. The study highlighted the need for more educational content and improved risk-benefit assessments to veterinary professionals and the public.

Conclusions: The results showed that the environmental impact of parasiticides is well recognised and an appreciation exists that more work needs to be done. Although the study findings captured clinicians’ motivation, a sizable fraction indicated scepticism in the risk-based approach’s ability to meet the required expectations, and in the readiness.

Control of parasites in companion dogs and cats poses challenges for clinicians and pet owners.

On one hand, blanket parasite treatment approach has been criticised for the potential overprescription of parasiticides, and the subsequent impacts on animal health and efficacy of parasiticides, in addition to the environmental dimension.

Another concern is the combination and broad-spectrum treatments, which may lead to excessive treatment, and increasing the risk of adverse reactions from drug side effects or drug‑drug interactions5.

On the other hand, a risk assessment‑based parasite control approach has limited generalisability, making practical implementation more time‑consuming and complex, particularly where owner understanding and compliance play such an important role.

Maximising the judicious use of current parasiticides warrants a more selective approach, targeted to high-risk animals, if such groups can be identified accurately.

The literature demonstrates efforts moving towards individualised parasiticide prescribing practices as an alternative to the one‑size‑fits‑all approach. In a recent study, the authors reported that 66% (79 of 119) of UK-based small animal clinicians agreed (30% [n = 36] strongly agreed) that the small animal veterinary profession should adopt a risk assessment‑based approach towards parasite control. Only 10% (12 of 119) veterinarians did not support the idea of seeing the profession adopting a risk assessment‑based parasite control approach. Those who provided a neutral response represented 24% (28 of 119) of the total responses6.

More recently, a collaborative venture between parasitologists and pharmaceutical companies has resulted in the development of risk assessment digital questionnaires, such as MyPet Persona, or a parasite risk assessment form that can be accessed via a QR code displayed on a waiting room poster for cat owners to complete before their consultation.

These tools aim to engage pet owners in helping clinicians to recommend parasite protection that matches the circumstances of individual pets.

Despite the growing interest in a risk assessment‑based parasite control approach – and the support provided by key advisory and regulatory bodies, including ESCCAP7–9, as well as the BVA, BSAVA and British Veterinary Zoological Society10 – challenges exist to the integration of this new treatment model into clinical practice and most small animal veterinarians have not fully changed their practice in response to this ongoing momentum.

The world veterinarians face today requires them to become more dynamic and willing to explore and adopt new approaches in what is a rapidly changing practice. They are working in a fast-paced, globalised world where research updates all the time, and new and emerging diseases – as well as related risk factors – are constantly in flux because of global climate change, the rise of pet travel and importation.

In such a complex context, newly emerging models for parasite control are encountered with many barriers. Conventional approaches to parasite control tend to still be adopted in favour of risk assessment‑based approaches to suit the protocols of employers, manage the needs and expectations of the majority despite individual requirements, and due to lack of a viable alternative to resource‑stretched, time‑poor clinicians6.

While the authors’ previous study6 acknowledged the potential of the risk assessment-based approach, small animal clinicians highlighted their struggle to see how it can be implemented and can satisfy the expectations of all stakeholders (veterinarians, practice policy and clients) – illustrating the need for well-rounded institutional support that guides them through this complex challenge.

In this present study, the authors aimed to obtain more insight into the perception of UK-based small animal clinicians of following a risk assessment‑based approach to preventive parasite control, by reflecting on the section of their previous survey6 dealing with attitudes towards risk assessment-based parasite control. The results of the present survey brought more insight about key areas to work on.

The design and implementation of the survey were reported previously6. Briefly, a questionnaire was produced in Jisc Online Surveys to collect data on attitudes of UK-based small animal veterinarians towards using risk assessment‑based preventive parasite control.

An initial survey was developed and pilot tested by three clinicians before wide distribution via social media and to active practice email addresses from the RCVS website that were categorised as “small animal general practice” through an accessible URL link. This recruitment approach was used to ensure the diversity of study participants.

The survey was active from 18 to 29 October 2021. Eligible participants were any current practising small animal veterinarian working in UK general practice.

The survey involved a Likert scale and collected information on attitudes towards risk assessment‑based parasite control, centred on 13 statements about the approach.

An optional free text question was provided for final participant comments on the topics covered in the questionnaire.

Data collected from the survey was exported into a spreadsheet and underwent data cleaning.

The anonymous survey was open to current practising small animal general practitioners working in the UK; respondents who did not meet this criterion were excluded from the analysis. Personal information collected for participants was removed prior to analysis to protect anonymity.

The present study focused on gaining more insight into small animal veterinarians’ attitude towards following a risk assessment‑based approach to preventive parasite control.

The participants were asked to read statements about risk assessment‑based parasite control and to select whether they “strongly agree”, “agree”, are “neutral”, “disagree”, or “strongly disagree” with each statement.

A total of 119 participants who matched the inclusion criteria completed the survey. The participants’ answers were used to assess their stance towards adopting such an approach.

Their answers to the statements are grouped into three categories – environmental concerns; efficiency and treatment outcome; and resources, roles and financial implications – with the largest number of statements being related to environmental concerns.

The survey included one open‑ended question, where the participants were given the opportunity to share their thoughts and comments on any of the topics covered in the survey. Only 33 of the 119 (28%) participants provided additional comments.

Overall, participants acknowledged that the survey was insightful (“all good questions”) and indicated this was “definitely an area that needs addressing!!”.

The participants’ free response regarding any further thoughts or comments on the topics covered in the survey provided useful insight because these responses captured veterinarians’ motivation – as well as scepticism – in their readiness to adopt a risk assessment‑based parasite control approach, and demonstrated their mixed and hesitant responses to the use of this new approach.

In what follows, the authors present the survey findings on the participants’ responses to specific statements and discuss the implications of these findings on future of parasite control practice.

Interestingly, 17% (n = 20) were neutral and only 2% disagreed.

One participant supported this statement, but with some reservations: “I think a risk assessment‑based approach would be better for pets and the environment, but realistically, there is little time to do this in practice unless clients were willing to attend specific nurse consults to discuss antiparasite treatment options.

“Trying to cram this into 15‑minute booster/sick pet appointments would lead to extra pressure on vets, confusion for owner then potentially reduced compliance, which, overall, would have a negative effect on parasite control compared to routine blanket treatment that currently occurs in our practice.”

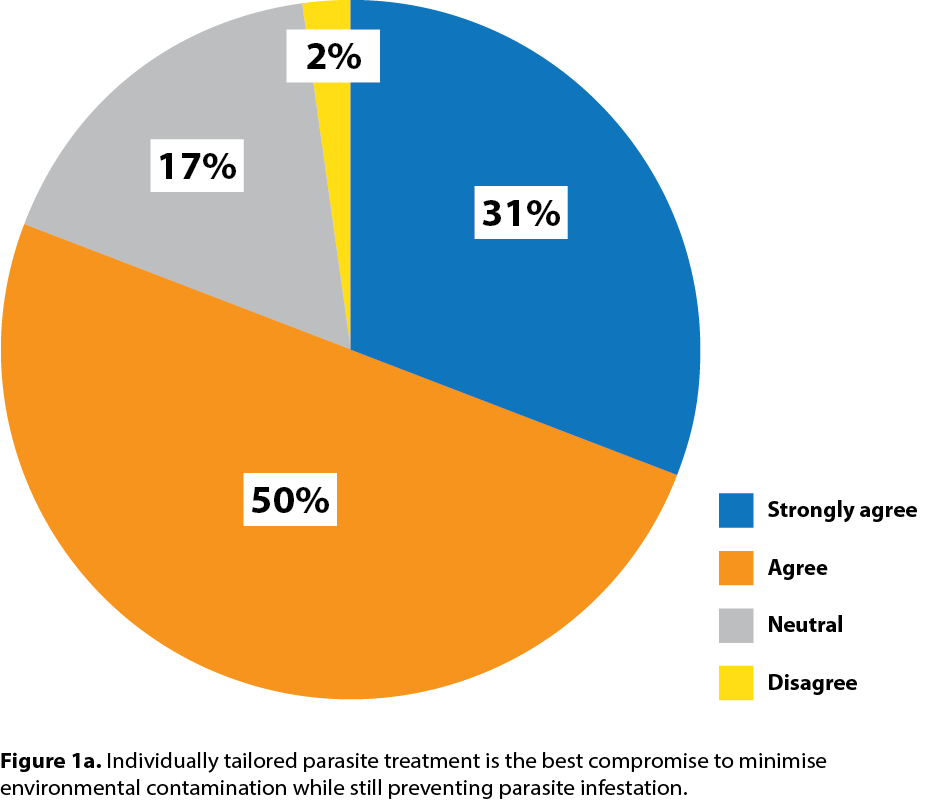

In contrast, 20% (n = 23) disagreed (3% strongly disagreed) with the statement, while 35% of responses were neutral (Figure 1b).

One participant noted: “General knowledge of parasite control ingredients is poor among many veterinary professionals, as is awareness of risks to humans.

“The geographic parasite maps are also largely unknown, although concern about the spread of vectors and parasites previously unknown to the UK that will, and do, affect pets – and have zoonotic potential – is growing with environmental changes.”

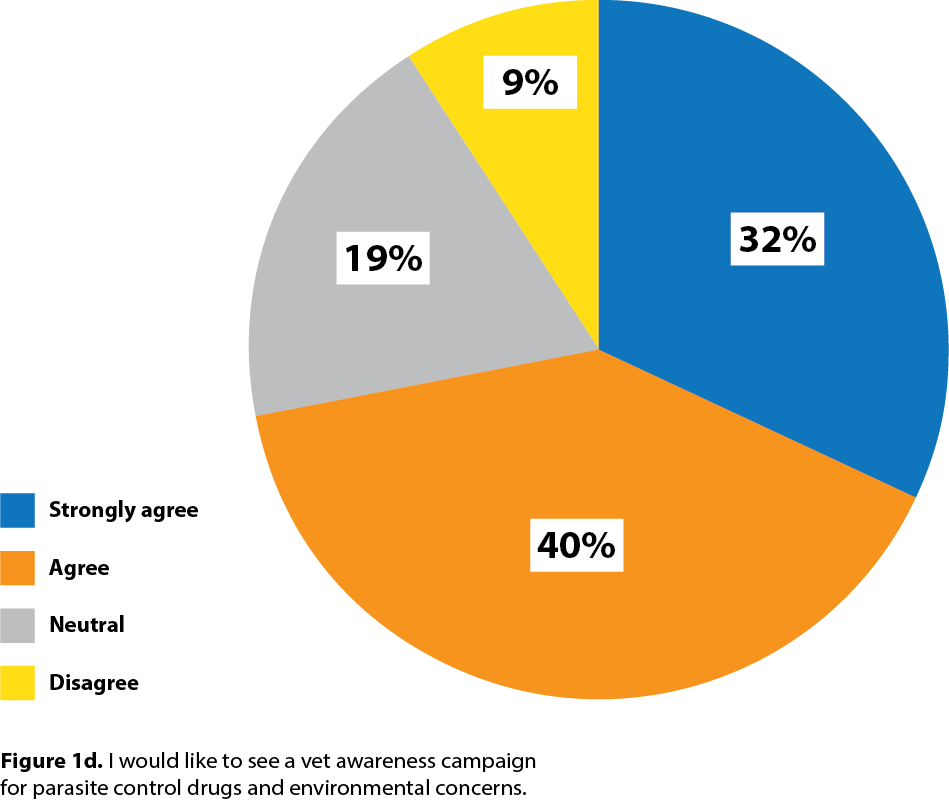

Interestingly, 3% disagreed and 11% were neutral (Figure 1c).

One participant noted: “Environmental impact is largely unknown, and the impact studies required by legislators are superficial and inadequate.”

One participant noted: “I would generally consider myself to be someone who is aware of, and concerned about, environmental issues. But for some reason – possibly lack of conversation around the issue? – this environmental concern doesn’t come into my decisions around prescribing parasite treatment. Think I will consider it more after doing this survey, thank you.”

One participant noted: “There needs to be more control over non‑prescription medication. Unless this is also addressed then it will be difficult to make any significant environmental impact by changing vet prescribing practices.

“Time needed to tailor these products will need to be charged to make viable. Some clients will see this as value if they are environmentally driven; others will perceive this as “profiteering”, especially if they receive less product at the end of it. This may then drive more people away from veterinary‑controlled products to the detriment of practice profit, but also potentially to animal welfare and neglecting any environmental benefits.

“Equally, more research must be done to assess environmental impacts before we are able to advise correctly.”

As anticipated, lots of enthusiasm existed about the role of veterinarians in protecting the environment. However, some participants felt the challenges were many.

For example, some do not feel they have a sufficient level of autonomy in the process: “We are part of a corporate, so there are only certain products we are allowed to use. We try where possible to tailor parasite control within the allowed products.

“Parasite control drugs being more targeted would reduce environmental impact, but if you are still needing coverage for the majority of parasites, would then having to use multiple products be worse?” Another participant noted: “I am very concerned about the environmental impact of routinely prescribed parasite treatment, but I am expected to prescribe based on our practice protocols and monthly care plans.”

In a paradoxical act of showing their autonomy, and to highlight their professional responsibility, many participants “relocated” the responsibility on external factors that can have more influence on what they can prescribe than what they personally or genuinely prefer.

One participant noted: “Definitely, I think we can be doing substantially more in practice. I’m not a fan of the rise of online non‑vet subscriptions as I don’t think this is helping the environmental side of the problem, particularly with the products that are dispensed – with what we’re seeing in our waterways in particular.”

Another participant said: “Many of the environmental concerns can be reduced by an increase in tablet‑type treatments. It is difficult to manage client feelings on this matter as we are fighting against ineffective or dangerous herbal remedies, and by raising concerns about our treatments in the wrong way we could play into their hands.”

Other participants have mentioned the need for more consult time as already stated, among other factors.

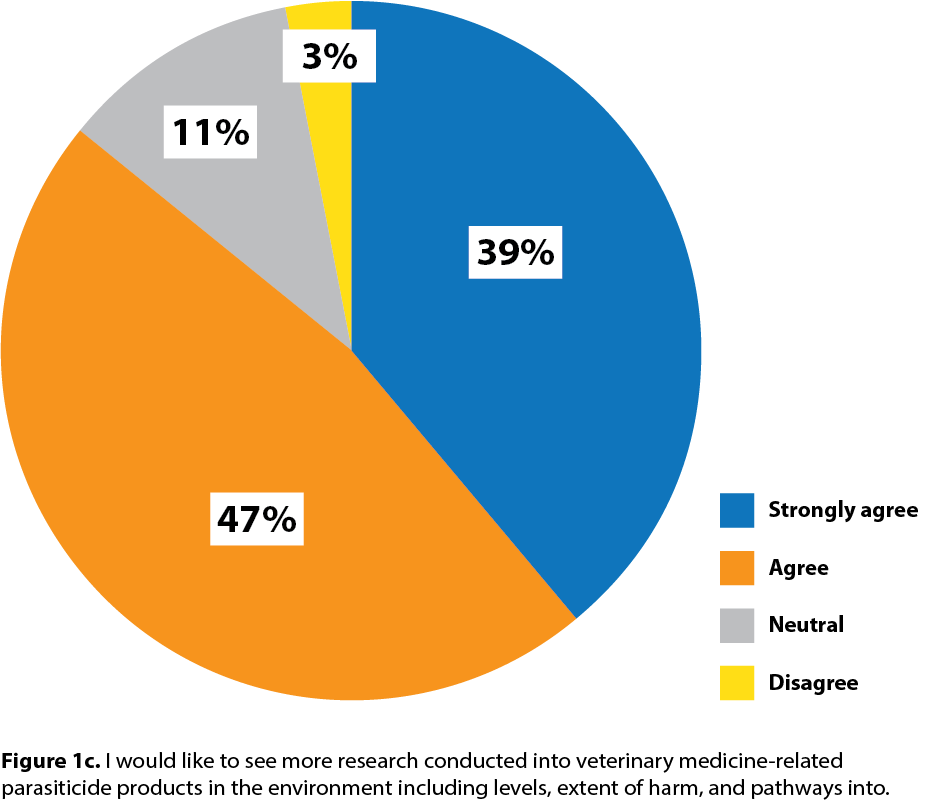

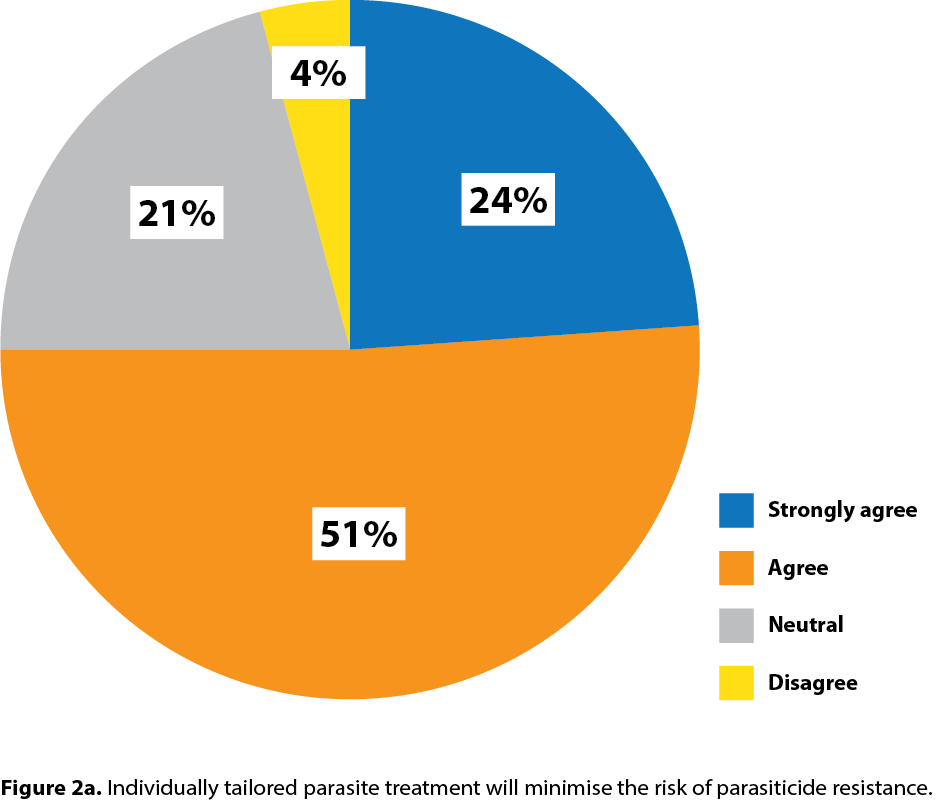

Only 4% of respondents (n = 5) disagreed with this statement and the responses of 21% (n = 25) were neutral.

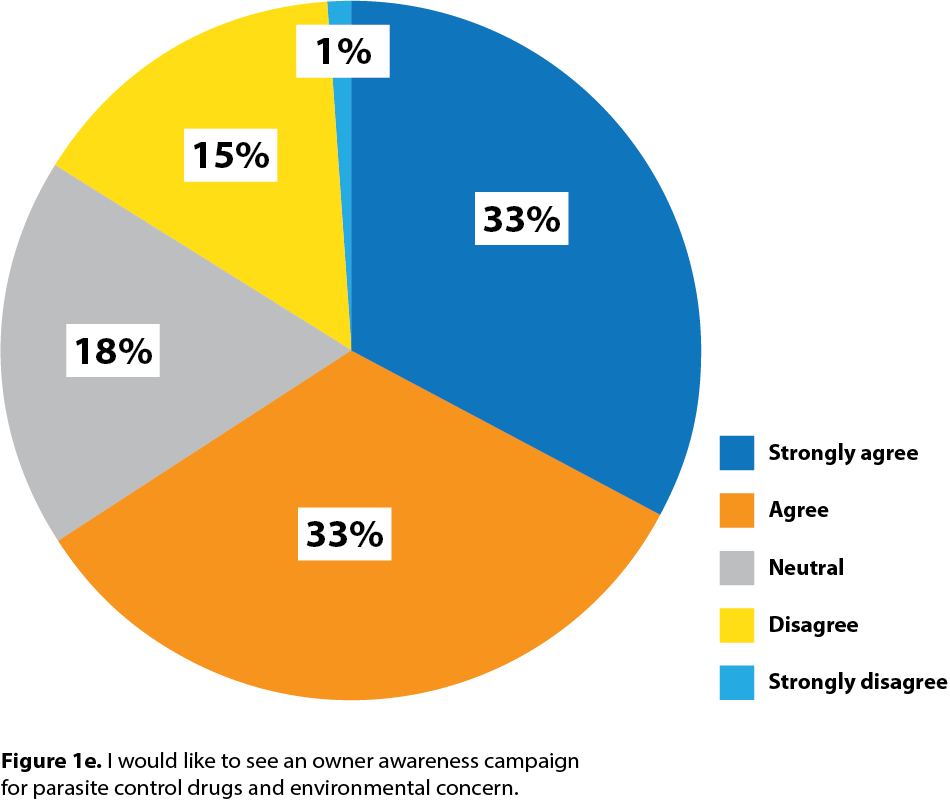

On the other hand, 19% (n = 22) and 3% (n = 4) disagreed or strongly disagreed, respectively.

Those with neural responses represented 32% (n = 38) of the total (Figure 2b).

Although an obvious appreciation of the beneficial impact of risk-based approach existed, in terms of limiting drug resistance and adverse effects, some of the comments provided indicated some doubts among clinicians about the use of this approach.

Interestingly, many of the comments show that some clinicians still prefer the blanket approach because of the lack of any evidence for drug resistance: “I am well versed in anthelmintic resistance in equids and follow very tailored regimes, including faecal egg counts, but I find the documentation of small animal anthelmintic effectiveness limited.”

Many participants challenged the idea that risk‑based approach can offer a better efficacy than the blanket approach, as shown in the following responses:

“Although obviously not ideal, a blanket approach towards parasite control is arguably effective and necessary in cases where animal owners struggle to – or do not want to – understand the risk assessment‑based approach and can, therefore, help to improve compliance and therefore reduce the risk/parasite burden of many animals.”

“While I am happy to move away from it if the individual would benefit, I am happy that our pet health care plan parasite control regimes are appropriate for local risk, so in most cases will prescribe them as standard. I don’t feel this means the individual is not properly planned for.”

“We do often see big flea outbreaks in animals that are fleaing with products from the shop [generic AVM-GSL products, for example]. While I’m very keen on trying to swap to risk-based treating, I do worry we’ll end up with more of these outbreaks, and then the costly and difficult treatment required to get them back under control.”

“We must be careful that we don’t swing too far away from antiparasitic use (and encourage a public anti their use), otherwise we will end back up with anaemia kittens wrought with worms, FAD cases and increased lungworm fatalities.”

“I have no choice but to blanket treat animals on the [corporate health care plan], but otherwise try to tailor treatment. Drugs overused in 80% of pets and underused in 20% I only treat my elderly dog for endoparasites once a year . My cat more frequently has not seen fleas on either of them. Dog has occasionally ticks, which I remove.”

“Due to lack of compelling risk factors and the zoonotic risk, year-round flea control is required as part of a risk-based approach. Vets should not be demonised for pursuing year-round flea treatment, or indeed ‘blanket’ treatment if they feel it is the right thing to do.”

“Concern re datasheets/licensing – will we put ourselves at risk professionally if we use the products at lower frequency, for example, and an animal becomes unwell? Google has a lot to answer for.”