10 Mar 2022

Before I go to sleep – patient considerations pre-anaesthesia

Sarah Little outlines handling, behavioural and environmental aspects in animals pre-medication.

Image © Monkey Business / Adobe Stock

Anaesthesia is a complicated area where great care and consideration should be taken into account before the patient is even pre-medicated. My role as an anaesthesia assistant considers both patients’ emotional and physical well-being during what is undoubtedly a stressful time for them.

“It is essential to reduce the stress of admission and hospitalisation to minimise the release of catecholamines (for example, epinephrine) into the circulation…” (Duncan, 2009).

Handling considerations

Communication is always vital, and it’s important to ask questions before handing the patient, such as:

- How old is the patient? This question in particular is aimed towards older patients that may be arthritic, as having limbs extended could cause them significant discomfort. Suitable bedding should be provided for all patients, but it is always nice for older patients to have a bit of support for their joints.

- What breed is the patient? Brachycephalic breeds can be more at risk of regurgitation – by keeping the head elevated until the endotracheal tube cuff is suitably inflated, the risk of them inhaling any fluids is greatly reduced. Airway obstruction “…is more likely to occur in the pre-anaesthetic period or during recovery from general anaesthesia when the airway is unprotected and reflexes are diminished due to anaesthetic drugs” (Beard, 2009).

- What is the procedure? This gives you an idea of how to best handle your patient. For example, if it’s a left forelimb fracture, you don’t want to be touching that particular leg. Patients with spinal injuries need special care when handling. Often they are unable to move or their movement is significantly restricted. Minimal neck extension is advised, and usually these patients are induced while in the lateral position.

- What is the temperament of the patient? Aggressive and anxious patients can make handling more difficult. It is, therefore, our responsibility to ensure they are suitably restrained in a way that does not cause them further distress. Consideration for how to handle patients showing signs of fear, anxiety, and stress (FAS) should always be implemented to ensure no members of staff get injured and to allow the anaesthetist to carry out the necessary treatment.

Behavioural considerations

It is incredibly important to be patient with patients that are wrongly viewed as being “naughty”.

Often, people are anxious about visiting the hospital, and that’s with the basis that we are there to improve our health. Our patients don’t have that knowledge or understanding – they are placed in an unfamiliar environment with strange people, sights, smells and sounds. They can react in ways they feel are appropriate – especially when they feel painful, sick or threatened.

With young patients that are hospitalised, it presents a good opportunity for staff members to create a positive association for them while they are in an unusual environment (Figure 1). Kind words and reassurances can help make them feel more settled, and it can hopefully ensure that future veterinary visits are less stressful.

With some patients a “less is more” approach is best. By that, judge how the patient is feeling via its body language – particularly during examination. Does the patient shy away from contact? Does it seem more at ease when sitting with you?

Talk to the anaesthetist and work around your patient and what it needs. Sometimes simply sitting with the patient is all the restraint that is required.

Try to encourage the patients towards you rather than pulling them on the lead. The author usually finds if she puts herself in a cage (Figure 2) while the patient watches, it seems to feel somewhat more reassured and is more likely to cooperate and go into the cage itself.

When it comes to behavioural considerations we should also look at ourselves before dealing with our patients. Try to maintain a calm demeanour, and if you feel yourself becoming frustrated or stressed for whatever reason then it may be worth taking a step back if you are dealing with a patient showing signs of FAS.

It’s perfectly understandable that in this profession you are bound to feel these emotions at some point, and the best way to recognise this is by addressing those feelings and taking the appropriate action. Have a cup of tea, go outside and take deep, relaxing breaths. Our patients can pick up on our emotions and it won’t help their emotional distress if they sense our own “negative” feelings.

If pre-medication has to be given intramuscularly, it is sensible to assume the patient may react in some way. The author personally finds that speaking to the patient in a calm, relaxing manner helps to keep the patient calmer, rather than using high-pitched voices.

With cats it’s usually easier if they are pre-medicated in a suitable cat carrier. Simply by lifting the lid and putting a blanket over their head can be the right amount of restraint required. Gentle reassurances should always be encouraged. No loud voices or sounds.

Environmental considerations

Plan in advance as to where patients will be placed. Dog-aggressive patients and cats should not be facing dogs, or if this is not possible, have something such as a blanket to cover the cage door so the patient cannot see.

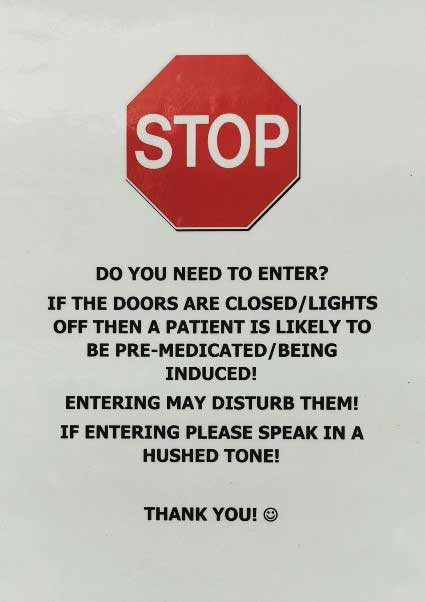

In circumstances where the patient has behavioural considerations, signs can be of great use. They can be placed on a patient’s cage and it provides a visual reminder to members of staff as to the patient’s emotional requirements. They can also be used in the area where induction will be taking place to remind people to use quiet tones while in the presence of premedicated or pre-induction patients (Figure 3).

The use of synthetic pheromones can help make the hospital environment less threatening. Ensure the patient has a “safe space” to retreat should it ever feel overwhelmed. This could be a kennel for a canine patient or a box with a blanket draped over it for a feline patient. Ideally a blanket should be placed over patients after pre-medication to reduce the risk of hypothermia developing.

If nervous patients are placed in a cage and they shy away from human contact it is then best to leave them alone – it is unwise to stand in front of them or to stare at them. Some may certainly benefit from the company, whether that’s sitting next to them or in with them depending on their stress levels. Small touches such as that can help bring a great deal of comfort.

Handling during induction

It is vital the area where induction of anaesthesia is taking place remains as quiet as possible, as patients are more rousable by noises during this stage. “Anaesthesia should be induced in a calm and quiet environment” (Freeman, 2009).

Ensure you have a good hold on the leg the IV catheter is in to allow the anaesthetist to give the necessary drugs and to guarantee that the catheter stays secure.

Excitement can occur during induction of anaesthesia where even the most sedated of patients can suddenly become reactive. This is good to remember as often the patient can respond to this phase in a way where it appears that it suddenly becomes more agitated. Be prepared for this to happen and ensure you have suitable restraint of the patient.

For cats, this may mean carefully wrapping them up in a blanket so that they do not escape from the area of induction. They should be in a room where no risk exists of them climbing on top of high surfaces or getting out.

“Propofol, a commonly used IV anaesthetic agent, is known to at times cause pain sensation upon injection in humans” (Nishimoto et al, 2015). It can therefore be assumed our patients could also potentially feel pain if propofol is administered.

If a risk of aspiration exists, the patient may need to have its head kept in an upright position. In these circumstances a towel can be used to prop the head up (Figure 4).

“Gastroesophageal reflux (GER) is defined as retrograde passage of gastric contents into the oesophagus” (Adams et al, 2015). “The incidence of GER in anaesthetised dogs has been reported to range between 12.5 per cent and 60 per cent” (Wilson et al, 2005; Viskjer and Sjöström, 2017).

When holding the patient’s head up, the author usually uses her middle finger and thumb to support the back of the skull. Holding them by the scruff isn’t just unethical, it also doesn’t give you the best support for the head and, therefore, can cause problems when the anaesthetist is trying to intubate the patient. It can also obscure the view of the larynx.

With the author’s role helping with induction of anaesthetics, she usually communicates to the anaesthetist about what the patient is doing while she is carefully restraining it. She will relay back information, such as head position and if the patient is becoming more relaxed. Take great care if opening the patient’s mouth so that you do not get bitten while checking its jaw tone – an unconscious patient can still potentially bite.

Place the tube tie behind the patient’s canine teeth. This will help to anchor the tie in place while the head is lifted up. Special consideration should be given to brachycephalic breeds with short muzzles and bulging eyes. The author will check if the anaesthetist is happy with how she is holding the head and if any adjustments are required.

With larger breed dogs it is always advisable to have an extra pair of hands to make everyone’s job a bit easier. While someone supports the head, another person can help keep the airway open by holding the tube tie.

It is often better to induce these kinds of dogs on the ground as opposed to the table before induction, as the risk exists of the patient not being fully sedated enough to tolerate being lifted and placed on a high surface.

Lifting large-breed dogs should be done with great care so as not to injure anyone or cause anyone to drop the patient. Tables that can be lowered down are highly advised in these cases. This technique works better as often these breeds of dogs aren’t as used to being lifted up on to tables, unlike smaller-breed dogs.

Never be afraid to ask for help if necessary. It can be beneficial to have someone distracting the patient or supporting its back end while the required treatment is given.

Conclusion

Ultimately, regardless of patient, gentle handling techniques should always be carried out appropriately.