8 Jul 2025

Brachycephalic patients: considerations of behaviour and stress management

Deborah Caunter RVN highlights behaviour and stress management in brachycephalic patients, including complications with breathing difficulties, ocular issues and pneumonia, and discusses the phenomenon of co-recovery.

Image: Vantage/ Adobe Stock

Brachycephalic breeds are becoming more popular, with a 1,527% rise in French bulldog Kennel Club registrations between 2010 and 2019 (Nutbrown-Hughes, 2020).

Despite this rise, brachycephalic breeds suffer from lifelong conditions such as brachycephalic obstructive airway syndrome (BOAS), ocular issues and a low tolerance for stress and heat.

Behaviour and stress management

Dogs communicate similarly when interacting with other dogs or humans but rely heavily on visual cues. Brachycephalic breeds have lost the ability to display facial expressions or cue with their tail, and so it can be challenging for them, not only to be able to deliver the visual cues, but also for other dogs to receive those cues and to react appropriately (Siniscalchi et al, 2018).

Stress increases their demand for oxygen and can exacerbate signs of respiratory distress, and can make handling in the veterinary practice more challenging, especially preoperatively – anxiolytic medications are recommended to aid in reducing stress and relaxing the smooth muscle in the trachea and nasal passages, preventing a risk of obstruction (Packer and Tivers, 2015).

Stress management of these patients prior to visits to the vet is of crucial importance.

Any heightening of respiratory effort caused by stress or excitement can increase the negative airway present and cause further narrowing of the trachea, resulting in hypoventilation, hypoxaemia, hypercapnia and eventually airway collapse (Grubb et al, 2022). Owners should be given anxiolytic medications prior to attending the vets to aid in reducing their pets’ stress levels (Jones, 2025).

Complications

Ocular complications

Many brachycephalic breeds are commonly affected by ocular problems and currently represent 25% of all canine patients seen at the ophthalmology department at the RVC, with patients as young as three months being presented (RVC, 2022).

Brachycephalic ocular syndrome (BOS) is a term used to describe any eye problems associated with the poor conformation of these breeds.

This process can result in corneal ulcers, with brachycephalic breeds being 20 times more likely to be affected or pigmentation and proptosis (Nutbrown-Hughes, 2020).

A study found that only 27% of corneal ulcers presenting required fluorescein staining, while the remaining 73% were so evident they did not require this test to be diagnosed (Costa, Steinmetz and Delgado, 2021).

In brachycephalic cats, due to a malformation with the nasolacrimal course, we can see that the tear drainage is affected (Sebbag and Sanchez, 2022). Opioids can also reduce tear production for up to 36 hours and with these reduced corneal sensory nerve fibres and their high susceptibility to corneal ulcers, eye lubrication should be considered for postoperative care for owners to administer at home (Scales and Clancy, 2020).

Proptosis (exophthalmos) is present in many of our brachycephalic patients, and any ocular contact with blankets, scrub solutions, fur or other items can make damage to the eye and ulcers more likely (Grubb, 2022).

During medical and surgical procedures, nurses should ensure the patient is properly positioned to alleviate any external pressure on the eye and apply eye lubrication before, during and after the anaesthetic and more regularly than they would a mesocephalic patient (Grubb, 2022).

Breathing difficulties, BOAS, cardiovascular and gastrointestinal concerns

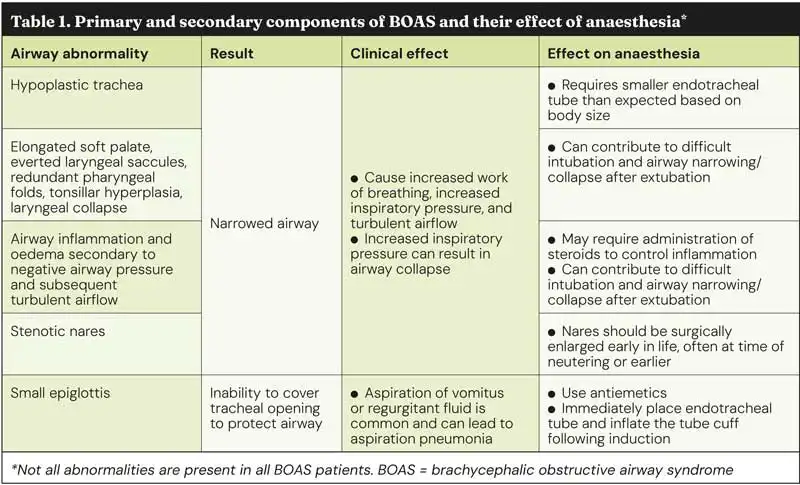

While many brachycephalic breeds have BOAS disease, the degree at which they have it varies. Some primary and secondary components are listed in Table 1 (Grubb, 2022).

It is highly recommended that surgical corrections in relation to BOAS should be done at an early age, as this can reduce the severity of some BOAS-related congenital abnormalities, for example, everted laryngeal saccules and laryngeal collapse. Surgical corrections can also reduce the risk of requiring subsequent anaesthetic procedures while increasing the safety of them (1.57 times more likely to have intraoperative complications and 4.33 times more likely to have post-anaesthetic complications) and, above all, improve quality of life (Grubb, 2022).

Cardiovascularly, these patients suffer with a much higher vagal tone than other dogs and so may display rapid and profound bradycardia on tracheal manipulation, for example, during surgery, intubation and extubation (Grubb, 2022).

Atropine, an anticholinergic, could provide some benefit with mild bronchodilation, providing that the patient has not had an alpha-2 agonist such as dexmedetomidine (Mathews, Killos and Graham, 2011).

Brachycephalic patients that present with these respiratory signs may also have pre-existing gastrointestinal concerns, too, such as esophagitis, gastroesophageal reflux, gastritis and hiatal hernias, as well as a high risk of aspiration pneumonia (Grubb, 2022).

A hiatal hernia is a risk factor for gastric reflux, as is fasting, and so brachycephalic patients should be fasted for less than six hours prior to their anaesthetic/sedation with a small meal approximately three hours beforehand, as this has been shown to reduce reflux (Grubb et al, 2020).

While no clear recommendation exists with regards to gastroprotectants and/or prokinetics, they are suggested to be used in dogs presenting with gastrointestinal signs and/or severe BOAS (Marks et al, 2018).

Aspiration pneumonia

Brachycephalic patients are at a much higher risk of aspiration pneumonia. This is due to an increased pressure in getting air into the lungs and so extra effort is exerted to compensate for this in an attempt to draw more air and, as a result, more material into the lungs (Darcy, Humm and ter Haar, 2018). In one study involving brachycephalic patients, 4.7% of dogs were affected with aspiration pneumonia preoperatively (Torrez and Hunt, 2006). Another study found that brachycephalic breeds are 3.77 times more likely to contract aspiration pneumonia than all other breeds with age of onset being approximately six to eight months (Darcy, Humm and ter Haar, 2018).

Nurses can play a vital role in assessing and identifying these patients in practice. They can recognise changes in patients and identify signs of respiratory distress or any abnormalities on thoracic auscultation – 70% to 75% of aspiration pneumonia cases had abnormal sounds present on thoracic auscultation (Tart, Babski and Lee, 2010).

Once these patients have been recognised, the nurse’s role becomes even more paramount in monitoring for a decline in condition and providing supportive care to aid the patient’s comfort and ultimately survival.

Antibiotics, airway management, oxygen therapy, administration of coupage, physiotherapy and gastrointestinal management are all areas nurses can assist with (Egleston, 2018).

Co-recovery with clients

Recent studies have been conducted to investigate the phenomenon of co-recovery with clients. One study looked at 63 brachycephalic dogs who underwent BOAS surgery with 42 of them having a co-recovery with the owner and the remaining 21 have a standard recovery without the owner’s present (Camarasa et al, 2023).

The key finding was surprisingly in regards to post-operative complications – those patients that had the standard recovery without the owners present had a high postoperative complication rate at 28% than those that recovered with the owners – 2% (Camarasa et al, 2023). None of the patients that recovered with the owners required any assistance after their discharge and while this is a relatively small study, the findings support the idea that owner-assisted recovery and early discharge is safe and possible and may also decrease the incidence of any postoperative complications (Camarasa et al, 2023).

However, Lindsay et al (2020) disagrees and out of the 248 dogs who underwent BOAS surgery, 18 (7.3%) had dyspnoea managed with oxygen therapy, 22 (8.9%) required anaesthesia and reintubation to manage to dyspnoea, 22 (8.9%) required a temporary tracheostomy tube to placed, 10 (4%) had aspiration pneumonia and 6 (2.4%) had a respiratory or cardiac arrest within 12 or more hours post-surgery.

These findings support the pre-existing theory of close monitoring for a minimum of 24 hours after BOAS surgery.

There is only the paper by Camarasa et al (2023) to base the findings of an owner-assisted recovery, so more investigating is required to determine the safety and patient benefit of this recovery method.

Additional nursing care

Regardless of if these patients will be undergoing surgery, the nurses can play a vital role in supporting owners and educating them about their pets. Initially, educating owners – many believe these signs are “normal” but as nurses, our job is to educate them in a way that does not make them feel ashamed, as a client’s trust is so important (Jones, 2025).

With a client’s trust, long-term management strategies can be put into place and discussions can be had to ensure their pet is getting the care it requires.

Weight management consultations will aid in minimising airway resistance, educating owners on avoiding stress, heat and overexertion and recommending veterinary surgeon consultations when gastrointestinal signs present themselves (Jones, 2025).

Conclusion

The continued popularity of brachycephalic breeds will continue to pose problems in the veterinary industry. Veterinary professionals should all understand the risks they pose and treatment options, as well as management of these patients to include gentle handling and support pre, post and during anaesthesia.

BOAS is an increasingly common condition, but it is manageable and by familiarising ourselves with the signs and techniques required, veterinary nurses can make a significant difference to these patients and use their skillset along the way.

References

- Camarasa JJ, Gordo I, Bird FG, Vallefuoco R, Longley M and Brissot H (2023). Owner-assisted recovery and early discharge after surgical treatment in dogs with brachycephalic obstructive airway syndrome, J Small Anim Pract 64(11): 680-686.

- Costa J, Steinmetz A and Delgado E (2021). Clinical signs of brachycephalic ocular syndrome in 93 dogs, Ir Vet J 74(1): 3.

- Darcy HP, Humm K and ter Haar G (2018). Retrospective analysis of incidence, clinical features, potential risk factors, and prognostic indicators for aspiration pneumonia in three brachycephalic dog breeds, J Am Vet Med Assoc 253(7): 869-876.

- Egleston S (2018). The forgotten complication: aspiration pneumonia in the canine patient, Vet Nurse, available at www.theveterinarynurse.com/content/clinical/the-forgotten-complication-aspiration-pneumonia-in-the-canine-patient

- Grubb T, Sager J, Gaynor JS, Montgomery E, Parker JA, Shafford H and Tearney C (2020). 2020 AAHA anesthesia and monitoring guidelines for dogs and cats, J Am Anim Hosp Assoc 56(2): 59–82.

- Grubb T (2022). Anesthesia and analgesia in brachycephalic dogs, Today’s Vet Pract September/October 2022, available at https://todaysveterinarypractice.com/anesthesiology/anesthesia-and-analgesia-in-brachycephalic-dogs/

- Jones L (2025). BOAS patients: How to manage them successfully as a vet nurse, Vet Intern Med Nursing, available at www.veterinaryinternalmedicinenursing.com/blog/episode-63

- Lindsay B, Cook D, Wetzel JM, Siess S and Moses P (2020). Brachycephalic airway syndrome: management of post-operative respiratory complications in 248 dogs, Aust Vet J 98(5): 173-180.

- Marks SL, Kook PH, Papich MG, Tolbert MK and Willard MD (2018). ACVIM consensus statement: support for rational administration of gastrointestinal protectants to dogs and cats, J Vet Intern Med 32(6): 1,823–1,840.

- Mathews LA, Killos MB and Graham LF (2011). Anesthesia case of the month, J Am Vet Med Assoc 239(3): 307-312.

- Nutbrown-Hughes D (2020). Brachycephalic ocular syndrome, Vet Nurse 11(8), available at www.theveterinarynurse.com/content/clinical/brachycephalic-ocular-syndrome

- Packer RM and Tivers M (2015). Strategies for the management and prevention of conformation-related respiratory disorders in brachycephalic dogs, Vet Med Res Rep 6(1): 219–232.

- RVC (2022). Brachycephalic breeds and ophthalmology, RVC, available at www.rvc.ac.uk/research/focus/brachycephaly/health-issues/ophthalmology

- Scales C and Clancy N (2020). Brachycephalic anaesthesia, part 3: the post-anaesthetic period, Vet Nurse J 35: 16-18.

- Sebbag L and Sanchez RF (2022). The pandemic of ocular surface disease in brachycephalic dogs: the brachycephalic ocular syndrome, Vet Ophthalmol 26(S1): 31-46.

- Siniscalchi M, D’Ingeo S, Minunno M and Quaranta A (2018). Communication in dogs, Animals 8(8): 131.

- Tart KM, Babski DM and Lee JA (2010). Potential risks, prognostic indicators, and diagnostic and treatment modalities affecting survival in dogs with presumptive aspiration pneumonia: 125 cases (2005–2008), J Vet Emerg Crit Care 20(3): 319–329

- Torrez CV and Hunt GB (2006). Results of surgical correction of abnormalities associated with brachycephalic airway obstruction syndrome in dogs in Australia, Journal of Small Animal Practice 47(3): 150–154.