20 May 2025

Bronchial collapse – diagnosis and management of condition

Charlotte Lea BVSc, MRCVS discusses an issue that can affect any breed, but that is most commonly found in small and toy dogs.

Image: Dixi_ / Adobe Stock

Lower airway collapse is a pathological reduction in airway diameter. While tracheal collapse is a well-recognised cause of coughing and dyspnoea in certain breeds, recent studies have actually found that bronchial collapse is more common than tracheal collapse when looking at a population of small breed dogs presented for chronic coughing1.

Any breed and size of dog can be affected, but smaller, toy breeds are most commonly affected, with the poodle and Yorkshire terrier appearing to be particularly predisposed2. It is more common in older dogs, but younger dogs can also be affected.

The exact aetiology of the disease is uncertain, but it is considered most likely multifactorial, and a congenital component is possible3. Common presenting signs of bronchial collapse include chronic coughing, upper respiratory tract noise and decreased exercise tolerance. Secondary infections also occur, sometimes resulting in more acute tachypnoea and lethargy. In dogs with severe bronchial collapse, episodes of acute decompensation can occur, resulting in dyspnoea and cyanotic episodes.

Diagnosis

Bronchial collapse is a dynamic process, and so bronchoscopy is required to assess the dynamic function of the lower airways.

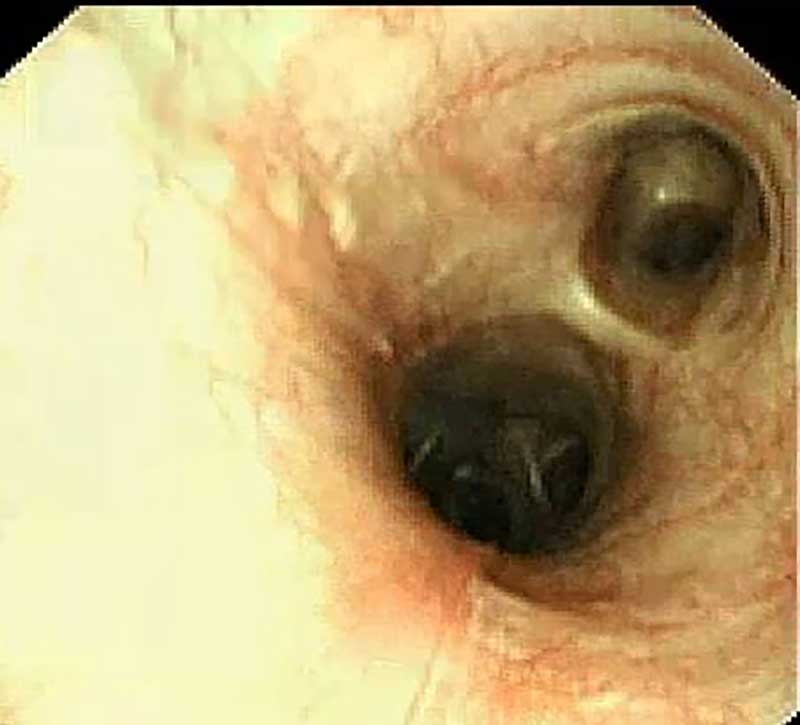

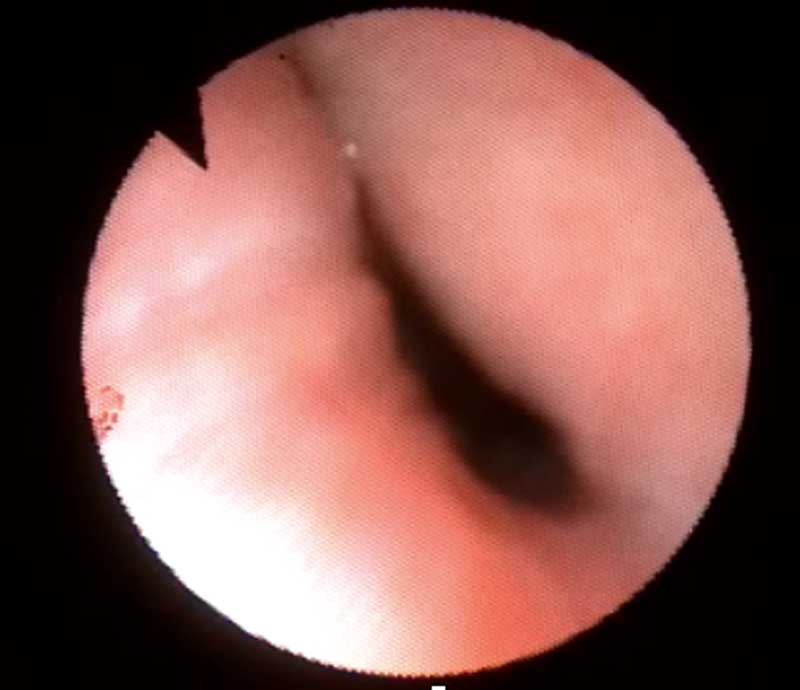

Bronchoscopy is the gold standard method of diagnosing and also grading bronchial collapse1,3. Figure 1 demonstrates the difference with bronchoscopy between a healthy dog and a dog with left mainstem bronchial collapse. Both radiographs and CT are suboptimal for the diagnosis of the airway collapse; however, these imaging modalities are important for assessing for other airway pathology, such as concurrent bacterial pneumonia or inflammatory airway disease.

Up to half of dogs that have bronchial collapse also have bilateral disease; the others tend to have predominantly the left bronchus collapsed3. Bronchoalveolar lavage is advised during diagnostic investigations. This often reveals mixed or pure neutrophilic inflammation on cytology1, with 85% to 100% of dogs thought to have concurrent inflammatory airway disease3.

Bacteria may be seen in the case of secondary bacterial infections, and performing a culture can be informative and guide the need for antibiotic therapy. PCRs for other respiratory pathogens such as Bordetella species, Angiostrongylus vasorum, mycoplasma, coronavirus, parainfluenza and adenovirus can be performed on the bronchoalveolar lavage fluid to investigate other respiratory pathogens that may be contributing to the respiratory disease – particularly in the face of acute deterioration.

Pulmonary hypertension is a possible sequelae, and so echocardiography could be considered to evaluate pulmonary hypertension and concurrent diseases.

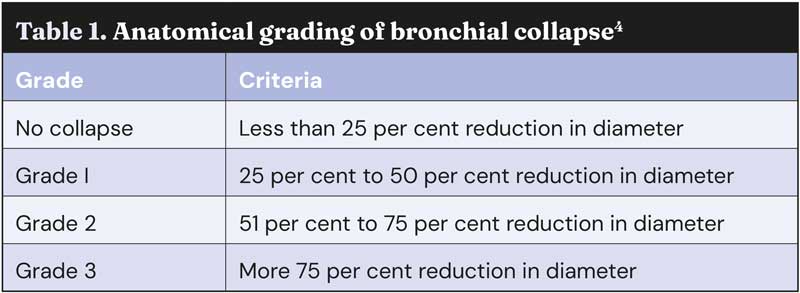

Anatomical grading for bronchial collapse

Based on human literature, a criteria for anatomical grading for bronchial collapse has been suggested. This can be seen in Table 1.

Treatment

Medical management

Initially, once diagnosed, we aim to manage dogs with lifestyle modifications. Ensuring appropriate bodyweight/body condition is a key part of management of airway collapse, since it is a critical exacerbating factor. Minimising over-exertion and over-excitement, and environmental management (such as reducing smoke and dust exposure, and using a harness instead of a collar) are also important.

Following this, medical therapy with the aim of reducing airway inflammation and minimising coughing can be trialled. Steroids (oral or inhaled) can be used if evidence of airway inflammation is documented. Antitussives such as diphenoxylate or codeine can be used to minimise coughing and prevent cyanotic episodes caused by coughing episodes, although they should be used with caution since this can mask progressive disease, and the long-term impact of suppressing this protective mechanism of mucus expulsion is unknown4.

Treating secondary bacterial infections can be beneficial in helping clinical signs and should ideally be based on culture and sensitivity from bronchoalveolar lavage where possible. Doxycycline can be beneficial for its immunomodulatory effect on the respiratory tract, as well as its antibiotic properties. Any other comorbidities should be managed appropriately.

Bronchial stent placement

Unfortunately, bronchial collapse is often progressive. Dogs may become refractory to medical management, and they can eventually develop life-threatening clinical signs, or have symptoms so marked that their quality of life is greatly impacted. If we confirm that the bronchial collapse is isolated to either the left or right mainstem bronchus, it is possible to perform a procedure called bronchial stenting in these dogs with severe disease.

Bronchial stenting is a last-resort procedure, and owners must be warned that placement can cause stimulation of cough receptors, resulting in ongoing coughing. Most dogs that have stents placed do require long-term antitussives; however, bronchial stent placement provides a minimally invasive and quick way to improve the patency of the airway and, in turn, reduce clinical signs significantly for these dogs.

These dogs have markedly improved quality of life, as opening the airways can reduce exercise intolerance and prevent episodes of cyanosis and dyspnoea.

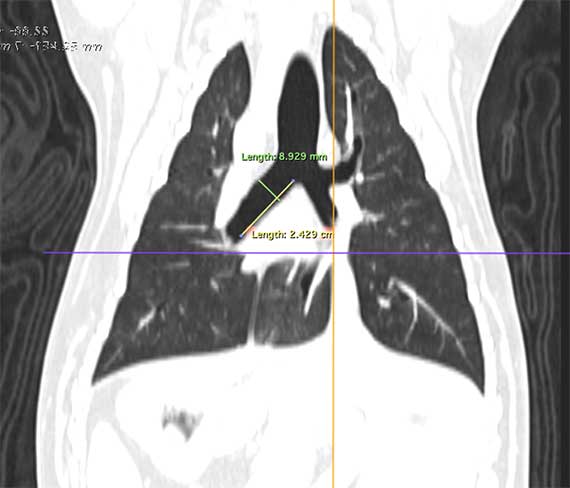

At Southern Counties Veterinary Specialists, we are one of only a very small number of referral hospitals in the UK offering bronchial stenting for these dogs. When we have a dog we feel may be a candidate for a bronchial stenting (refractory to medication, normal body condition score, no concurrent respiratory pathology), prior to bronchial stent placement, a CT scan of the thorax must have been performed, as this is necessary for us to be able to calculate the appropriate stent size.

On the CT scan, we measure the width and length of the collapsed bronchus, as seen in Figure 2. We chose a stent diameter that is 1mm to 2mm greater than the maximal diameter of the measured bronchus to avoid migration. The stent reported diameter and length corresponds to the diameter and length the stent would be if not compressed at all. The final length, once deployed, will depend on the difference between the airway diameter and the diameter the stent can open to (estimated on CT scan) and will be longer than reported. The manufacturers provide a chart to allow us to estimate the length once deployed, so we can choose a stent that should be matching the length measured on the CT scan.

Once we have determined this, the stent can be placed with fluoroscopic guidance, with the help of flexible bronchoscopy.

With the patient under general anaesthetic, bronchoscopy is used to visualise the collapsed area of bronchus. Markers are then placed on the skin to act as landmarks that can be seen on fluoroscopy once the bronchoscope has been removed.

The bronchoscope is also used to place a guide wire into the bronchus we intend to place the stent in. Once we are satisfied with our landmarks, the stent is guided very slowly into place over the previously placed guide wire with the assistance of fluoroscopy (Figure 3).

Fluoroscopy is used continuously so that the stent can be visualised at all times as it is deployed very slowly over the guide wire. Once deployment is complete, bronchoscopy is then performed to confirm correct positioning (Figure 4); radiographs may also be obtained to help confirm this (Figure 5).

Prognosis

Following placement, dogs are recovered in our intensive care unit. They are normally hospitalised overnight and generally are able to return home the following day. Possible complications that owners, and vets, need to be aware of following placement are stent migration, stent fracture, tissue ingrowth into the stent that could cause obstruction, and bacterial pneumonia (since the stent can act as a nidus for infection) and ongoing cough3.

Most dogs will have an ongoing cough, perhaps due to concurrent inflammatory airway disease or since the stent may stimulate cough receptors within the airways. Fortunately, in these animals coughing rarely impacts quality of life. However, many dogs will benefit from remaining on antitussive treatment following bronchial stenting.

In a recent case series published by our hospital, 100% of cases had improvement in quality of life post-bronchial stenting, despite ongoing coughing3. Therefore, it is considered to be a worthwhile procedure in dogs with severe bronchial collapse refractory to medical management.

To conclude, bronchial collapse should be considered as a differential diagnosis for any dog – particularly if small breed – with chronic cough, upper respiratory tract noise and exercise intolerance.

The symptoms should be investigated appropriately, and prompt diagnosis of bronchial collapse can allow management to be implemented early in the disease course, helping to maintain quality of life for these dogs for as long as possible.

Bronchial stent placement can be considered in dogs with mainstem bronchial collapse that are refractory to medical management.

- Use of some of the drugs in this article is under the veterinary medicine cascade.

- This article appeared in Vet Times (2025), Volume 55, Issue 20, Pages 13-15

References

- 1. Singh MK, Johnson LR, Kittleson MD and Pollard RE (2012). Bronchomalacia in dogs with myxomatous mitral valve degeneration, J Vet Intern Med 26(2): 312-319.

- 2. Adamama-Moraitou KK, Pardali D, Day MJ, Prassinos NN, Kritsepi-Konstantinou M, Patsikas MN and Rallis TS (2012). Canine bronchomalacia: a clinicopathological study of 18 cases diagnosed by endoscopy, Vet J 191(2): 261-266.

- 3. Kelly D, Juvet F, Lamb V and Holdsworth A (2023). Bronchial collapse and bronchial stenting in 9 dogs, J Vet Intern Med 37(6): 2,460-2,467.

- 4. Reinero CR and Masseau I (2021). Lower airway collapse: revisiting the definition and clinicopathologic features of canine bronchomalacia, Vet J 273: 105682.