15 Mar 2025

Cathy Woodlands BSc(Hons), VNPA, GradDipVN PGCertAVN (Anaesthesia and Analgesia), RVN outlines the important processes teams must consider when confronted with burn trauma patients.

Figure 1. An initial burns injury, in this instance involving a heat pad. Image: Lara Dempsey / Blaise Referrals

Burns are injuries that damage the skin’s two primary layers, caused by extreme temperatures, caustic substances, electricity or radiation (Curtis, 2019).

Prompt and proper first aid can significantly reduce the severity of the damage caused by the burn.

This article will explore essential first aid procedures, along with strategies for wound management and pain management in burn trauma patients.

Thermal burns can be either dry thermal burns, which can occur when anaesthetised or recumbent patients are unable to move away from a heat source – such as a heat pad (Figure 1) – or wet thermal burns, which are caused by a hot liquid such as boiling water from a pan or kettle.

If the burn is due to a thermal injury, then the initial treatment involves applying cool running water directly on to the burn wound. This has been reported to improve long-term healing if the cooling is performed within three hours of the initial injury (Jenkins, 2018).

The treatment of chemical burns is similar, with lukewarm water being used for up to 30 minutes to remove any of the contaminant. If contact with the eyes has occurred, then flushing with clean water or saline for 15 minutes is required.

Any wounds need to be protected by covering the affected area with a sterile, non-adherent dressing to prevent contamination and further irritation, avoiding adhesives that may damage delicate tissue.

In some cases, the owner may not witness the cause of the burn, and the skin damage may not be immediately noticeable, leading to a delayed presentation of the injury. This is where a thorough history is necessary to try to identify the causative agent that the animal has been exposed to.

Triaging veterinary patients with burns involves prioritising care based on the severity of the injury, the animal’s overall condition and the potential for life-threatening complications, ensuring that the most critical cases receive immediate attention.

These patients should receive the normal triage assessment, including evaluating the patient’s overall condition (including the major body systems), and classified as stable or unstable and given a triage score denoting the case urgency and waiting time (Gerrard, 2024).

With patients with burn injuries, other details that should be noted are the percentage of body and surface area affected, and the cause of the burn identified, if known. If the burns are due to a fire, then consideration must be taken into the potential for smoke inhalation and the immediate need for oxygen therapy.

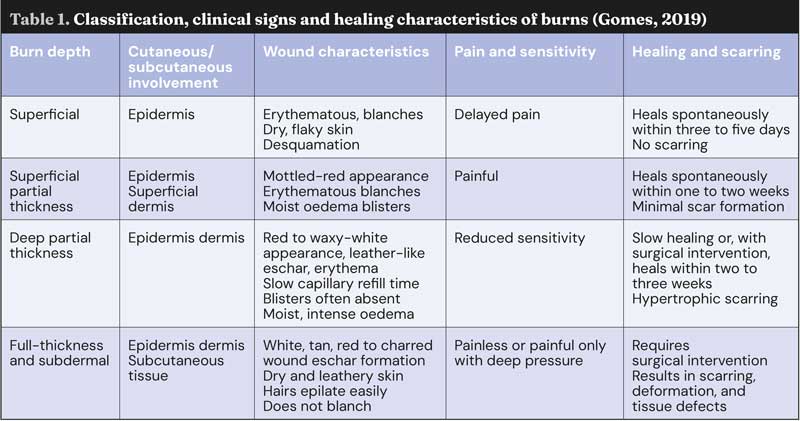

Burns are classified according to the size and depth of the injury. Superficial burns affect only the outer epidermis, whereas superficial partial-thickness burns involve the epidermis and superficial dermis.

Deep partial-thickness burns extend through the epidermis into the deep dermis. Full-thickness and subdermal burns damage the epidermis, dermis and subcutaneous tissue, affecting fat, tendons, muscles, bones, and interstitial tissue (Gomes, 2019; Table 1).

Burn depth also varies across the affected area and can have differences in appearance.

The total body surface area (TBSA) affected by thermal burns can be estimated using the “rule of nines” – 9% is the head or each thoracic limb; 18% equates to dorsal trunk, ventral trunk or each pelvic limb. Burns affecting less than 20% TBSA are local, while those for more than 20% TBSA are severe and may cause systemic issues. However, these figures, derived from human medicine, may overestimate affected areas in animals due to greater skin elasticity, and should be used as a rough guide (Low, 2022).

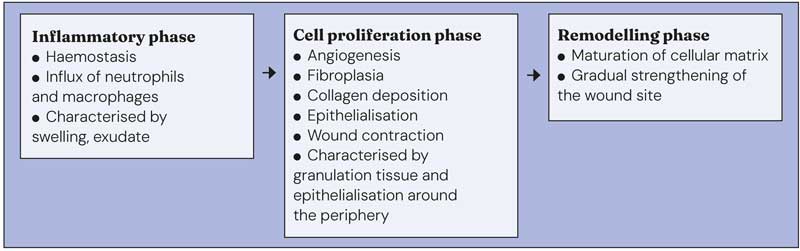

The wound healing process can be seen in Figure 2.

There are four stages of wound management: debridement, lavage, dressing application and closure. Firstly, we cover the wound with a sterile gauze swab or use sterile lubricant to protect the wound from contamination, and clip the hair around the wound.

Next, the wound is lavaged using isotonic saline, which is the ideal lavage solution, as it removes the bacteria and debris without causing harm to the cells associated with the wound-healing process (Woodlands, 2014).

Following lavage, the wounds should be gently probed for depth and extent, and then covered with a non-adherent sterile dressing until the patient has been stabilised and definitive treatment is possible (Peterson, 2020).

Secondary tissue healing refers to the process by which a wound heals when it cannot close directly or if significant tissue loss has occurred, resulting in the formation of scar tissue.

Open wound healing, or second intention healing, occurs in injuries with significant skin loss, such as lacerations and burns.

Various dressings can be used to aid debridement, granulation and scar formation. Some wounds first require initial granulation tissue to form, to reduce the wound size before surgical closure, known as secondary closure (third intention healing; Winkler, 2012).

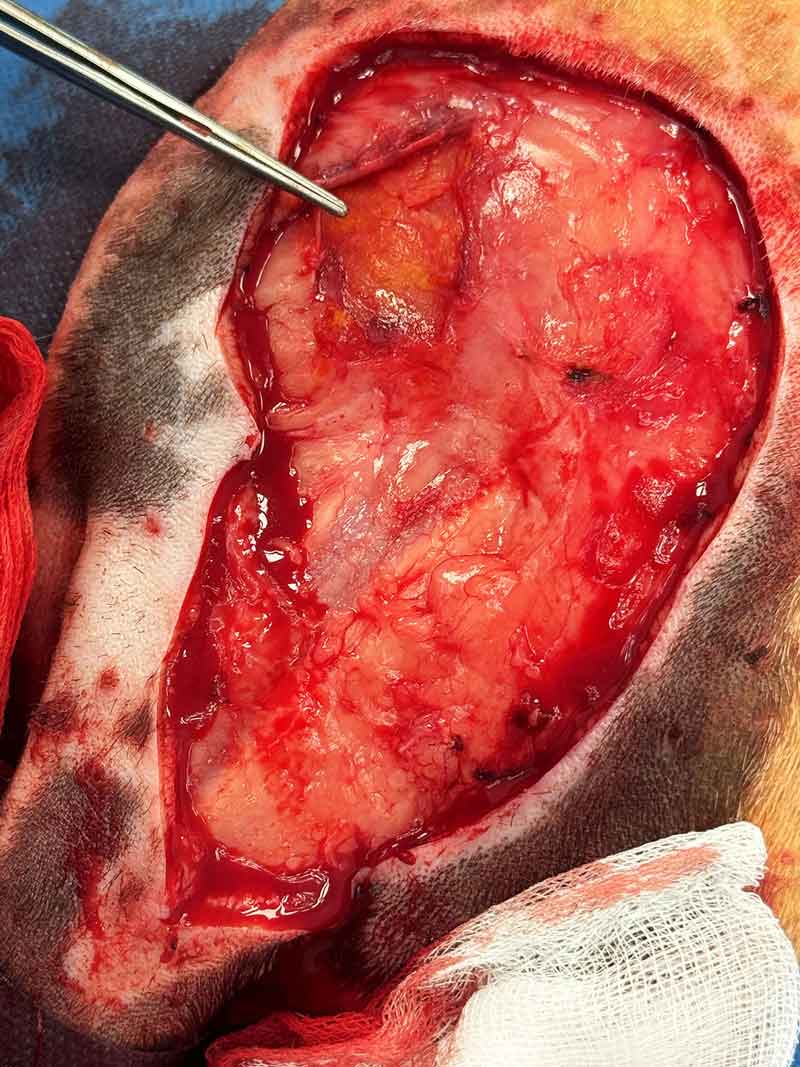

For partial to full-thickness wounds, invasive debridement is often needed. Sharp surgical debridement is typically preferred, with the technique depending on muscle or bone involvement.

For deep burns without muscle or bone exposure, tangential debridement removes tissue in thin layers until viable tissue is reached (Curtis, 2019).

After the debridement (Figure 3) and lavage process, it is important to take photographs and measurements of the wound to monitor progress throughout the patient’s recovery. This also allows for continuation of care and monitoring of the wound progression throughout the healing process.

All bandage changes should be performed with a strict aseptic technique to maintain infection control. A few considerations are needed when choosing dressing materials, including the burn depth, exudate production, location of the wound and the stage of healing (Figure 4).

Time is important when assessing wounds to allow any non-viable tissue to declare itself; therefore, the debridement stage of the wound healing process can be delayed for a short period, allowing the healthy tissue to be identified first before the debridement process. The ideal dressing to promote granulation tissue formation is one that provides an appropriate wound healing environment – it should be non-restrictive, non-adherent and sterile, and provide a moist environment to accelerate the healing process (Caldwell, 2014).

In veterinary medicine, wound dressings depend on the severity and stage of wound healing. Common options include:

Dressing selection should be based on burn depth, exudate levels and infection risk. Depending on the location of the wound, bandages or tie-over dressings may be required to hold the dressing in place during the wound healing process.

Burn patients experience significant pain, requiring multimodal analgesia throughout hospitalisation, and the analgesia plan should be individualised, considering any pre-existing health conditions.

On initial presentation, a full opioid such as methadone, can be administered and used throughout the hospitalisation period. Using a validated pain score, such as the Modified Glasgow Pain Score for dogs and cats, each patient’s analgesic requirement can be assessed and adjusted as necessary.

Procedural pain is anticipated during debridement and dressing changes, requiring escalated analgesia.

Multimodal analgesia can be integrated into the sedation or anaesthesia protocol, including the use of α2 adrenergic agonists, benzodiazepines and ketamine (Low, 2022).

While hospitalised, patients can also benefit from continuous rate infusions (CRIs) such as fentanyl and ketamine. CRIs are advantageous over intermittent boluses, as they sustain drug action by maintaining plasma concentration, whereas intermittent boluses cause fluctuating levels that decline after peaking; therefore, CRIs prevent the peaks and troughs of drug action (Taylor, 2014).

Pain management should also be considered for cases with chronic pain, which can occur due to wound contracture – particularly over high-motion areas, and where surgical scar revision may be required (Jenkins, 2018).

Effective management of burn patients requires both wound care and pain management.

Correct dressing selection, infection prevention and pain relief strategies are essential for promoting healing and improving patient comfort.