29 Jul 2025

Canine acute diarrhoea: ENOVAT review on use of antimicrobials

Bryn Jones BVM, BVS, CertAVP, DipECVIM-CA, MRCVS provides a summary of the European Network for Optimization of Veterinary Antimicrobial Treatment’s systematic review and guidelines on this topic

Image: Barbara Helgason / Adobe Stock

Antimicrobials have frequently been used in the treatment of dogs with both acute and chronic diarrhoea1-4; metronidazole and amoxicillin appear to be the two most used5,6.

A decade ago, 63% to 70% of diarrhoeic dogs in the UK were prescribed antibiotics, with increased usage when diarrhoea was haemorrhagic (more than 80%)3,4.

More recent evidence from Denmark and the UK has shown a lower use of 31% to 50%6,7. Their continued use goes against previous guidelines advising that most bacterial pathogens cause self-limiting diarrhoea, and use of antimicrobials could be more harmful than beneficial and induce resistance8,9.

Last year, a multidisciplinary panel undertook and published a systematic review and meta-analysis to assess the evidence relating to any benefit of antibiotic use in canine acute diarrhoea (CAD)10.

This informed the production of guidelines for the European Network for Optimization of Veterinary Antimicrobial Treatment (ENOVAT), European Societies of Clinical Microbiology and Infectious Diseases (ESCMID) and ESCMID Study Group for Veterinary Microbiology11.

The review and guidelines did also consider the evidence surrounding nutraceuticals, but this summary will focus on antimicrobials only.

What causes CAD?

Despite being so common, the causes and optimum treatment for CAD are poorly studied. Acute gastroenteritis/colitis are likely the most common causes by far.

Causes of acute gastroenteritis include dietary intolerance or sensitivity, infectious organisms (viral, bacterial, parasitic or protozoal), toxin ingestion, scavenging, reaction to medications and trauma from foreign body ingestion12-19.

In a significant number of cases, an underlying cause is not identified. Many other systemic diseases can present as acute diarrhoea, but rarely without other clinical signs.

Numerous studies have demonstrated isolation of enteropathogens (both viral and bacterial) from healthy dogs without diarrhoea, sometimes in rates just as high as those with diarrhoea20; this includes Campylobacter and Salmonella species1,9,18,21,22-25.

It seems likely that Clostridium perfringens type F strains associated with “NetF” toxin release are a key virulence factor associated with the necrotic enterocolitis in many (but not all) dogs with “acute haemorrhagic diarrhoea syndrome” (AHDS; previously “haemorrhagic gastroenteritis”)16,26,27. AHDS is not transmissible, and differing triggers are potentially responsible for clostridial overgrowth16.

Many dogs with diarrhoea also have viruses isolated (40% to 60%), where the primary cause may not benefit at all from antibacterials14,28-31.

Arguments for antimicrobial use

Suggested motivation for antibiotic use in CAD has principally been to treat primary bacterial pathogens (presumed or confirmed) that could be causing diarrhoea (such as Campylobacter species, clostridial organisms or Salmonella species). Other possible reasons are attempts to positively influence secondary dysbiosis or preventing bacteraemia/sepsis from translocation through a compromised gastrointestinal barrier.

Hyperthermic and anorexic dogs were more likely to be prescribed antimicrobials, suggesting severity of illness and/or concern for sepsis are probably triggers for use4,6.

Haematochezia appears to increase the likelihood of antibiotic use – particularly in peracute/acute AHDS where dogs often are presented with vomiting, marked fluid losses and signs of systemic illness3,6,7,16,32-35. Increased antibiotic use in these patients is likely driven by concern for gut integrity, suggested by haematochezia, and because AHDS can present with findings that overlap with sepsis criteria36. Indeed, some have argued for the use of antimicrobials whenever haemorrhagic diarrhoea is present18.

As to why antimicrobials continue to be prescribed, despite guidelines and narratives often advising against it, the true reason is uncertain. One rationalisation could be the limited evidence base for treatment of CAD generally.

In the absence of large, high-quality studies, vets may understandably have doubts about relying on expert opinion alone, the lowest level of reliability in evidence-based medicine4,37. One prospective study has shown minimal benefit to metronidazole use in CAD25.

Arguments against antimicrobial use

Numerous studies have confirmed that an overwhelming majority of CAD, including AHDS, is self-limiting within days.

In veterinary medicine, antibiotics should only be prescribed when necessary, in line with global efforts to reduce avoidable use and subsequent risk of resistance38. In the majority of CAD, diarrhoea is mild and lasts for less than two days, but it is true that only 10% of cases are presented for veterinary attention, so the population we treat may have more severe disease than average19.

Primary bacterial gastroenteritis is considered very uncommon17,23,25,38,39. Viral, parasitic or dietary causes may be at least as prevalent. Multiple prospective studies have shown no benefit to antibiotic use in CAD, including AHDS, with regards to mortality, duration or severity27,39-42. Other retrospective or non-randomised studies agree6,7,43. AHDS does not appear to predispose to bacteraemia, and those with bacteraemia do not have increased mortality44. No evidence exists to suggest that treating enteric salmonellosis is necessary or effective9.

Alongside stewardship concerns, antimicrobials may also have direct adverse effects, such as immune-mediated disease, gastrointestinal upset and dysbiosis (the latter two are particularly pertinent in a patient that already has GI disease), though one study did not identify short-term adverse effects40,45.

Metronidazole can rarely cause severe adverse effects, even at licensed doses46. Negative dysbiosis consequences of antibiotics can persist for months after administration27,47,48.

Amoxicillin-clavulanate may predispose to resistant Escherichia coli39. Clostridial species appear to be developing resistance to metronidazole, particularly concerning given how debilitating human Clostridioides difficile infections can be49-51. Antibiotic-resistant Campylobacter species have also been documented21.

Metronidazole is frequently employed in canine gastrointestinal disease due to perceived importance of anaerobic cover. Potentiated amoxicillin should have broad activity against anaerobes typically present in the canine gastrointestinal tract51. When metronidazole was added to amoxicillin-clavulanate in AHDS, no benefit was found52.

What did the ENOVAT systematic review show?

Several studies have investigated the potential clinical benefit of antibiotics for CAD. However, these have often been small and sometimes reached differing conclusions.

Meta-analyses and systemic reviews can be used to reconcile this, by conducting statistical analysis across all studies combined, markedly increasing the overall certainty of evidence37,53.

The ENOVAT panel consisted of 18 members from a range of appropriate disciplines. Review and meta-analysis were performed using established techniques, namely Delphi questionnaires, PICO questions and GRADE methodology (focusing on clinical context) to ascertain certainty and quality of evidence. Only randomised control studies were included.

The review encompassed three PICO questions:

- In CAD, does antimicrobial treatment compared to no antimicrobial treatment have an effect?

- In CAD, does metronidazole have a superior effect compared to beta-lactams?

- In CAD, does long duration (more than six days) of antimicrobial treatment have a superior effect compared to short duration (less than seven days)?

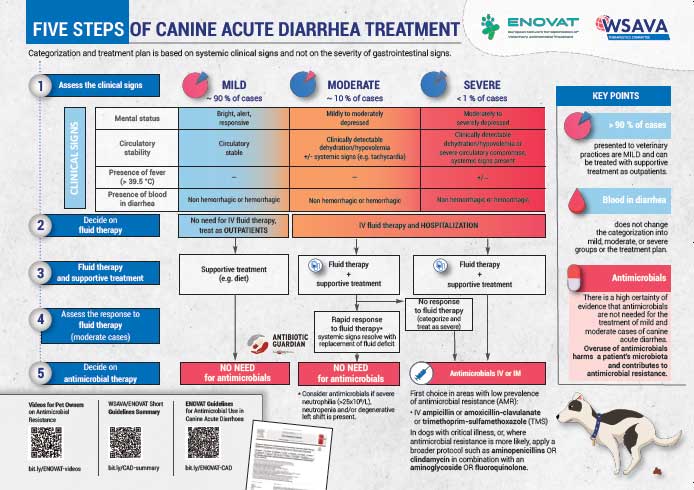

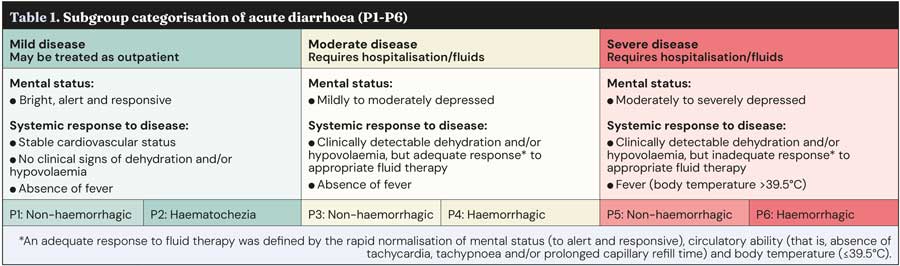

The review and guidelines were devised with clinical application in mind. To cover the broad range of signs and severity of CAD, six disease classifications (P1 to P6) were defined based on the severity of clinical signs, treatment indicated and whether faecal blood was present (Table 1).

Clinical significance is not always equivocal with statistical significance. Accordingly, interviews were carried out with both veterinary practitioners and dog owners to establish thresholds for what was considered “clinically beneficial”.

On this basis, the following thresholds were devised to define what clinical benefit entailed for each outcome:

- Reduction in duration of diarrhoea by at least one day.

- Reduction in duration of hospitalisation by at least one day.

- Reduction in progression of disease by at least 30% in mild forms, and 10% in more severe forms.

- Reduction in mortality by at least 3%.

The systematic review discovered six studies (encompassing 232 dogs) which fulfilled the criteria and could help to answer the PICO questions25,39-42,54. No studies unfortunately included dogs from the most severe disease classifications (P5 to P6), likely as many of these dogs could have a suspicion of sepsis that would make withholding antibiotics ethically unacceptable.

Meta-analysis revealed the following outcomes.

- In all dogs, antimicrobials reduced duration of diarrhoea by a trivial amount compared to placebo (mean reduction of 0.28 days, below threshold of clinical significance). This held true when both hospitalised and non-hospitalised dogs were analysed separately.

- The duration of hospitalisation was trivially reduced in dogs receiving placebo, compared to antimicrobials (mean reduction of 0.37 days).

- The risk of death was trivially increased in dogs receiving antimicrobials compared to placebo (anticipated 0.08% increase). Mortality only occurred in hospitalised dogs.

- The risk of disease progression was trivially increased in dogs receiving placebo compared to antimicrobials (anticipated 2% increase), based on only two dogs reported to show progression, both hospitalised at the time.

- Amoxicillin-clavulanate is marginally more efficient in shortening the duration of diarrhoea compared to metronidazole (mean reduction of 0.29 days). Certainty of evidence was very low, as no studies directly compared this; indirect comparison was performed.

- No studies directly compared the length of antimicrobial treatment. In eight studies that reported duration of outcome, diarrhoea rarely exceeded seven days (usually two to five days) and rarely lasted longer than the antibiotic course.

- No adverse effects of antimicrobial use were reported in any dogs.

The overall conclusion was that antimicrobial treatment did not have a clinically relevant effect for any outcome. The level of certainty was high for dogs with mild-moderate disease (P1 to P4), but low for severe disease (P5 to P6) due to the lack of representation. Risk of bias was considered low in most of the six studies.

Though trivial impact (both favourable and unfavourable) of antimicrobial treatment was reported for all outcomes, this never exceeded the pre-ordained clinical thresholds. Even in outcomes where antimicrobials showed clinically irrelevant benefit, the 95 % confidence interval was such that it also encompassed the possibility of a trivial negative effect, too.

While no signs of adverse effects were noted in the six studies, gastrointestinal signs have been reported in healthy dogs receiving antimicrobials including metronidazole55,56. As dogs with CAD already have gastrointestinal signs, it is possible that adverse effects could be masked.

Additionally, as the primary focus was clinically relevant outcomes, others such as resistance or dysbiosis may be missed.

What are the ENOVAT guidelines?

Based on the findings of the systematic review, several recommendations were generated regarding antibiotic usage.

Antibiotics not recommended (strong recommendations, high-certainty evidence):

- Antimicrobials are not recommended for dogs with mild-moderate CAD, both haemorrhagic and non-haemorrhagic (P1 to P4).

- Dogs with laboratory values indicating severe or overwhelming inflammation, such as severe neutrophilia (more than 25×109), neutropenia and/or degenerative left-shift, represent an exception.

Based on the input of owners and vets, the main concern in dogs with mild CAD is the duration of diarrhoea.

For dogs with haemorrhagic diarrhoea, the risk of progression is also of concern, and for dogs with moderate disease, concern exists for duration of hospitalisation and mortality. No clinical benefit was clear for any of these outcomes with antimicrobial use. The panel concluded that undesirable effects outweigh the desirable effects.

Antibiotic use (all conditional recommendations, low-certainty or very low-certainty evidence):

- Antimicrobials are recommended in dogs with severe CAD (pyrexic or non-responsive to fluids), both haemorrhagic and non-haemorrhagic (P5 to P6).

- Parenteral antimicrobial use is recommended, using drugs likely to be effective against bacterial translocation.

- In dogs with non-critical illness, penicillins (such as amoxicillin-clavulanate) or trimethoprim/sulphonamides are considered first line.

- In dogs with critical illness (severely depressed mental status, severe vascular compromise or shock, and where signs of organ dysfunction or sepsis may be present) or where resistance is likely (such as previous antimicrobial use, geographic variation, lack of response to first-line therapy), four quadrant coverage is recommended (such as amoxicillin-clavulanate and fluoroquinolone).

- Antimicrobial therapy should not extend beyond clinical resolution. For most CAD, three to seven days is likely adequate.

Dogs with severe disease have not been represented in any high-quality evidence studies, so no strong recommendations could be made. Severe disease contributes only a small proportion of CAD, potentially less than 1%6.

The panel concluded that in this population, the potential desirable effects of antimicrobials outweighed the undesirable. Identifying the animals with severe CAD that will benefit is challenging in the acute setting, and withholding treatment may pose a risk of progression to sepsis in some. Harmful effects are still possible, but considered of lesser importance.

How can we use the guidelines, and what are the barriers?

Clearly, the first step in deciding on suitability for antimicrobial therapy, and indeed any treatment plan, is to assess the disease severity based largely on a thorough clinical examination.

When outpatient therapy is suitable, antimicrobials are not recommended. For dogs requiring hospitalisation, most still do not require antimicrobials. The decision should be based on severity of clinical signs, response to fluid therapy, haematology results and any evidence of other organ dysfunction. When antimicrobials are required, they should be used promptly and parenterally, as the goal is to treat and prevent sepsis. Penicillins are likely appropriate for most scenarios, and the duration of treatment should be kept as short as possible.

It is important to remember that consensus statements are, at heart, “more what you’d call guidelines than actual rules”, in the words of Captain Barbossa. The final decision of whether to use antimicrobials rests with the treating vet. We are empowered to make treatment decisions that we believe are clinically justifiable. The ability to prescribe antimicrobial therapy is a privilege in this era of ever-increasing antimicrobial resistance.

No legal restrictions exist in the UK for use of antibiotics in small animals if considered medically beneficial. However, if we do not continue to improve our stewardship, and resistance increases, no guarantee exists that this will not change in the future. Implementing evidence-based recommendations is one tool at our disposal to conquer this threat.

The main motivators for antibiotic prescription for CAD are likely a combination of suspicion for causative bacterial infections, concern for progression or sepsis, and perception (real or perceived) that owners wish us to prescribe “something”. These can be combated through owner and veterinary education that focuses on the fact that primary bacterial causes appear uncommon, and with good evidence that CAD is self-limiting regardless of antibiotic administration.

The risk of progression and mortality in mild-moderate cases appears to be low to negligible. If owners or vets feel the need or desire to prescribe some form of therapy, then products with less risk of harm, such as probiotics or nutraceuticals, oral rehydration fluids or anti-emetics, may be able to fill the “void”.

The ENOVAT panel believed that most owners would wish to avoid the cost and effort of medication if aware that no clinically relevant benefits existed, and if informed of the potential harms of antimicrobial treatment to animals and humans. Ongoing education of the public regarding the risks posed by antimicrobial resistance will be helpful, and this is an area that veterinary professionals are encouraged to contribute to where possible.

Summary

Analysis of the existing quality evidence shows no benefit of antimicrobial use for most dogs with CAD; therefore, they are recommended in only the most severe and poorly responsive cases.

A primary strength of these guidelines was a focus on contextualised information and the involvement of both vets and dog owners on generation of the clinical questions.

These findings and recommendations support those advised in previous guidelines or narrative reviews, including the BSAVA PROTECT ME poster8,9,16,35.

- This article appeared in Vet Times (2025), Volume 55, Issue 30, Pages 9-13

- More on this subject is available in our clinical archive here.

Author

Bryn Jones qualified from the University of Nottingham in 2014 and moved into small animal general practice in south Wales for four years, where he completed a CertAVP. After completing a small animal medicine residency in Hampshire, he moved to Willows Referral Service in 2023, where he currently works. He has earned recognition as an RCVS and European specialist in small animal internal medicine. Bryn has an particular interest in hepatology, nephrology and especially gastroenterology.

References

- 1. Reineke EL et al (2013). Evaluation of an oral electrolyte solution for treatment of mild to moderate dehydration in dogs with hemorrhagic diarrhea, J Am Vet Med Assoc 243(6): 851-857.

- 2. Molina RA et al (2023). A multi-strain probiotic promoted recovery of puppies from gastroenteritis in a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study, Can Vet J 64(7): 666-673.

- 3. Jones PH et al (2014). Surveillance of diarrhoea in small animal practice through the Small Animal Veterinary Surveillance Network (SAVSNET), Vet J 201(3): 412-418.

- 4. German AJ et al (2010). First-choice therapy for dogs presenting with diarrhoea in clinical practice, Vet Rec 167(21): 810-814.

- 5. Hughes LA et al (2012). Cross-sectional survey of antimicrobial prescribing patterns in UK small animal veterinary practice, Prev Vet Med 104(3-4): 309-316.

- 6. Singleton DA et al (2019). Pharmaceutical prescription in canine acute diarrhoea: a longitudinal electronic health record analysis of first opinion veterinary practices, Front Vet Sci 6: 218.

- 7. Dupont N et al (2021). A retrospective study of 237 dogs hospitalized with suspected acute hemorrhagic diarrhea syndrome: disease severity, treatment, and outcome, J Vet Intern Med 35(2): 867-877.

- 8. Marks SL et al (2011). ACVIM Consensus Statement: enteropathogenic bacteria in dogs and cats: diagnosis, epidemiology, treatment, and control, J Vet Intern Med 25(6): 1,195-1,208.

- 9. Weese JS (2011). Bacterial enteritis in dogs and cats: diagnosis, therapy, and zoonotic potential, Vet Clin North Am Small Anim Pract 41(2): 287-309.

- 10. Scahill K et al (2024). Efficacy of antimicrobial and nutraceutical treatment for canine acute diarrhoea: a systematic review and meta-analysis for European Network for Optimization of Antimicrobial Therapy (ENOVAT) guidelines, Vet J 303: 106054.

- 11. Jessen LR et al (2024). European Network for Optimization of Veterinary Antimicrobial Therapy (ENOVAT) guidelines for antimicrobial use in canine acute diarrhoea, Vet J 307: 106208.

- 12. Cook S and Greensmith T (2020). Supporting the intoxicated patient: toxicants affecting the gastrointestinal and hepatobiliary systems, In Pract 42(7): 384-393.

- 13. Gainor K et al (2021). Novel cyclovirus species in dogs with hemorrhagic gastroenteritis, Viruses 13(11): 2,155.

- 14. Caddy SL (2018). New viruses associated with canine gastroenteritis, Vet J 232: 57-64.

- 15. Allenspach K (2015). Bacteria involved in acute haemorrhagic diarrhoea syndrome in dogs, Vet Rec 176(10): 251-252.

- 16. Busch K and Unterer S (2022). Update on acute hemorrhagic diarrhea syndrome in dogs, Adv Small Anim Care 3(1): 133-143.

- 17. Vessieres F and Walker D (2016). Managing acute gastrointestinal signs in cats and dogs: part 1, Vet Times, tinyurl.com/4ztx9wkw

- 18. Hall EJ (2018). Antibacterials in canine gastrointestinal disease, In Focus, tinyurl.com/3u38xpje

- 19. Hubbard K et al (2007) Risk of vomiting and diarrhoea in dogs, Vet Rec 161(22): 755-757.

- 20. Pintar KDM et al (2015). A systematic review and meta-analysis of the Campylobacter spp. Prevalence and concentration in household pets and petting zoo animals for use in exposure assessments, Plos One 10(12): e0144976.

- 21. Acke E (2018). Campylobacteriosis in dogs and cats: a review, N Z Vet J 66(5): 221-228.

- 22. Cave NJ et al (2002). Evaluation of a routine diagnostic fecal panel for dogs with diarrhea, J Am Vet Med Assoc 221(1): 52-59.

- 23. Herstad HK et al (2010). Effects of a probiotic intervention in acute canine gastroenteritis - a controlled clinical trial, J Small Anim Pract 51(1): 34-38.

- 24. Gizzi ABDR et al (2014). Presence of infectious agents and co-infections in diarrheic dogs determined with a real-time polymerase chain reaction-based panel, BMC Vet Res 10: 23.

- 25. Langlois DK et al (2020). Metronidazole treatment of acute diarrhea in dogs: a randomized double blinded placebo-controlled clinical trial, J Vet Intern Med 34(1): 98-104.

- 26. Gohari IM et al (2020). NetF-producing Clostridium perfringens and its associated diseases in dogs and foals, J Vet Diagn Invest 32(2): 230-238.

- 27. Reisinger A et al (2024). Comparing treatment effects on dogs with acute hemorrhagic diarrhea syndrome: fecal microbiota transplantation, symptomatic therapy, or antibiotic treatment, J Am Vet Med Assoc 262(12): 1,657-1,665.

- 28. Gomez-Betancur D et al (2023). Canine circovirus: an emerging or an endemic undiagnosed enteritis virus?, Front Vet Sci 10: 1150636.

- 29. Smith CS et al (2022). Identification of a canine coronavirus in Australian racing greyhounds, J Vet Diagn Invest 34(1): 77-81.

- 30. Hsu H-S et al (2016). High detection rate of dog circovirus in diarrheal dogs, BMC Vet Res 12(1): 116.

- 31. Martella V et al (2011). Astroviruses in dogs, Vet Clin North Am Small Anim Pract 41(6): 1,087-1,095.

- 32. Mortier F et al (2015). Acute haemorrhagic diarrhoea syndrome in dogs: 108 cases, Vet Rec 176(24): 627.

- 33. Busch K et al (2015). Clostridium perfringens enterotoxin and Clostridium difficile toxin A/B do not play a role in acute haemorrhagic diarrhoea syndrome in dogs, Vet Rec 176(10): 253.

- 34. Unterer S et al (2014). Endoscopically visualized lesions, histologic findings, and bacterial invasion in the gastrointestinal mucosa of dogs with acute hemorrhagic diarrhea syndrome, J Vet Intern Med 28(1): 52-58.

- 35. Unterer S and Busch K (2021). Acute hemorrhagic diarrhea syndrome in dogs. Vet Clin North Am Small Anim Pract 51(1): 79-92.

- 36. Reisinger A et al (2024). Evaluation of intestinal barrier dysfunction in dogs with acute hemorrhagic diarrhea syndrome, Animals 14(6): 963.

- 37. Howick J et al (2011). The Oxford Levels of Evidence 2, Oxford Centre for Evidence-Based Medicine, tinyurl.com/p38emfy7

- 38. Allerton F and Jeffery N (2020). Prescription rebellion: reduction of antibiotic use by small animal veterinarians, J Small Anim Pract 61(3): 148-155.

- 39. Werner M et al (2020). Effect of amoxicillin-clavulanic acid on clinical scores, intestinal microbiome, and amoxicillin-resistant Escherichia coli in dogs with uncomplicated acute diarrhea, J Vet Intern Med 34(3): 1,166-1,176.

- 40. Unterer S et al (2011). Treatment of aseptic dogs with hemorrhagic gastroenteritis with amoxicillin/clavulanic acid: a prospective blinded study, J Vet Intern Med 25(5): 973-979.

- 41. Shmalberg J et al (2019). A randomized double blinded placebo-controlled clinical trial of a probiotic or metronidazole for acute canine diarrhea, Front Vet Sci 6: 163.

- 42. Rudinsky AJ et al (2022). Randomized controlled trial demonstrates nutritional management is superior to metronidazole for treatment of acute colitis in dogs, J Am Vet Med Assoc 260(S3): S23-S32.

- 43. Pegram C et al (2023). Target trial emulation: do antimicrobials or gastrointestinal nutraceuticals prescribed at first presentation for acute diarrhoea cause a better clinical outcome in dogs under primary veterinary care in the UK?, Plos One 18(10): e0291057.

- 44. Unterer S et al (2015). Prospective study of bacteraemia in acute haemorrhagic diarrhoea syndrome in dogs, Vet Rec 176(12): 309.

- 45. Igarashi H et al (2014). Effect of oral administration of metronidazole or prednisolone on fecal microbiota in dogs, Plos One 9(9): e107909

- 46. Evans J et al (2003). Diazepam as a treatment for metronidazole toxicosis in dogs: a retrospective study of 21 cases, J Vet Intern Med 17(3): 304-310.

- 47. Huse SM et al (2008). Exploring microbial diversity and taxonomy using SSU rRNA hypervariable tag sequencing, Plos Genet 4(11): e1000255.

- 48. Torres-Henderson C et al (2017). Effect of enterococcus faecium strain SF68 on gastrointestinal signs and fecal microbiome in cats administered amoxicillin-clavulanate, Top Companion Anim Med 32(3): 104-108.

- 49. Spigaglia P (2016). Recent advances in the understanding of antibiotic resistance in Clostridium difficile infection, Ther Adv Infect Dis 3(1): 23-42.

- 50. Álvarez-Pérez S et al (2015). Faecal shedding of antimicrobial-resistant Clostridium difficile strains by dogs, J Small Anim Pract 56(3): 190-195.

- 51. Gobeli S et al (2012). Antimicrobial susceptibility of canine Clostridium perfringens strains from Switzerland, Schweiz Arch Tierheilkd 154(6):247-250.

- 52. Ortiz V et al (2018). Evaluating the effect of metronidazole plus amoxicillin-clavulanate versus amoxicillin-clavulanate alone in canine haemorrhagic diarrhoea: a randomised controlled trial in primary care practice, J Small Anim Pract 59(7): 398-403.

- 53. Hinchcliff KW et al (2023). ACVIM-Endorsed Statements: consensus statements, evidence-based practice guidelines and systematic reviews, J Vet Intern Med 37(6): 1,957-1,965.

- 54. Israiloff JV (2009). Vergleich von Therapieformen Der Idiopathischen Hämorrhagischen Gastroenteritis (HGEI) Beim Hund, dissertation, University of Veterinary Medicine Vienna.

- 55. Whittemore JC et al (2019). Randomized, controlled, crossover trial of prevention of antibiotic-induced gastrointestinal signs using a synbiotic mixture in healthy research dogs, J Vet Intern Med 33(4): 1,619-1,626.

- 56.Pilla R et al (2020). Effects of metronidazole on the fecal microbiome and metabolome in healthy dogs, J Vet Intern Med 34(5): 1,853-1,866.