2 Mar 2021

Canine congenital heart disease

Joon Seo discusses the case of a six-month male entire whippet in this entry into <em>Vet Times</em>’ regular Case Notes series.

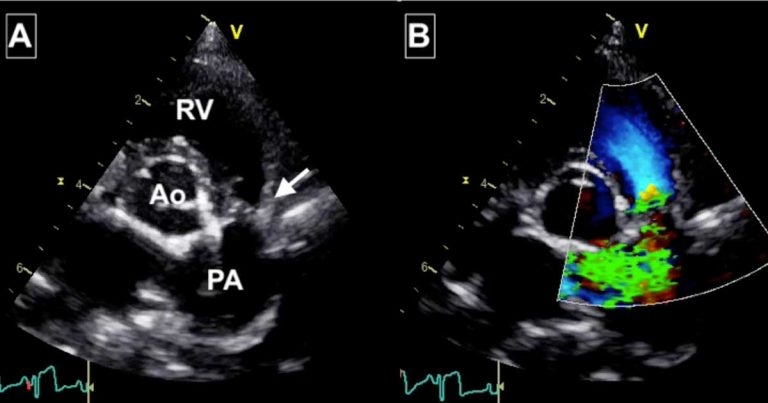

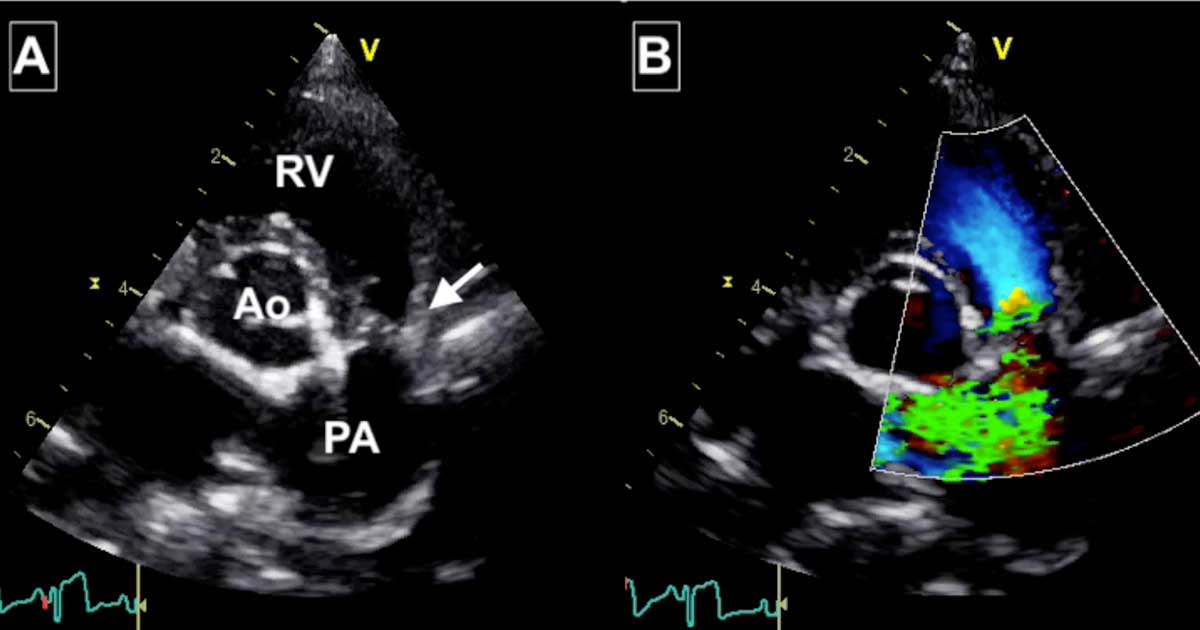

Figure 1. Images from Toby’s echocardiogram. (A) The arrow points at the stenotic lesion and shown fused thin valve leaflets. Post-stenotic dilation of the main pulmonic artery is evident distal to the valve. Abbreviations: Ao = aorta, PA = pulmonary artery, RV = right ventricle. (B) The colour Doppler image shows turbulence (green) originating from the fused valve, explaining the audible heart murmur.

Toby is a six-month-old male entire whippet that presents to you for a routine examination. Toby has recently been adopted by the owner and his previous medical history is unknown.

The client reports no concerns with Toby and indicates that he is exercising normally, and is otherwise bright and energetic. Physical examination is unremarkable apart from the surprise finding of a grade 5/6 left basilar systolic heart murmur.

Question

What are the differential diagnoses for Toby’s heart murmur and what would be the next diagnostic step?

Answer

A loud left basilar systolic heart murmur in a puppy is most consistent with congenital heart disease, with pulmonic stenosis and subaortic stenosis being the most common causes. Another differential would be tetralogy of Fallot, which would usually be associated with cyanosis and exercise intolerance.

An atrial septal defect is an unlikely differential in this case as it is generally associated with a low‑grade left basilar systolic murmur. Physiological or innocent murmurs are also unlikely as they are usually quiet murmurs (grade I-II/VI and rarely grade III/VI).

Innocent puppy murmurs usually disappear by four to six months of age, although some adult dogs (including whippets) can have a soft physiological murmur at any age. To identify the cause of a murmur, an echocardiogram is the next recommended step.

Follow-up

Toby was referred to a cardiology specialist and Doppler echocardiography was performed. Severe hypertrophy of the right ventricular free wall and interventricular septum existed, which was considered secondary to malformation of the pulmonic valve. This consisted of fused, but thin and mobile valve leaflets consistent with the diagnosis of pulmonic stenosis (Figure 1).

Pulmonic stenosis is a congenital heart disease where the pulmonic outflow tract is obstructed at either the subvalvular, valvular or supravalvular level. Most dogs have fused valve leaflets, but other malformations or mixed morphologies of pulmonic stenosis are possible.

The prognosis for pulmonic stenosis varies with the severity of obstruction, which is measured using Doppler echocardiography. The amenability to balloon dilation depends on a number of factors, including the morphology of the lesion. For Toby, the pressure gradient was consistent with severe pulmonic stenosis, but the valve leaflet morphology (thin and mobile leaflets) made him a good candidate for balloon valvuloplasty.

Dogs with mild pulmonic stenosis often live a normal life, whereas dogs with moderate pulmonic stenosis have a more varied outcome — especially where concurrent tricuspid valve regurgitation is identified. Untreated severe pulmonic stenosis has a more guarded prognosis with a high risk of development of right-sided congestive heart failure, arrhythmia, collapsing episodes and sudden death. For this reason, treatment is advised for severe pulmonic stenosis.

Treatment options for pulmonic stenosis include minimally invasive transvenous balloon valvuloplasty. This procedure involves accessing the heart percutaneously via the jugular or femoral vein. Once the balloon catheter is placed across the stenotic area, the balloon is inflated to alleviate the obstruction and the balloon catheter is then removed.

Other treatment options in severe cases that are refractory to balloon valvuloplasty include open heart surgery.

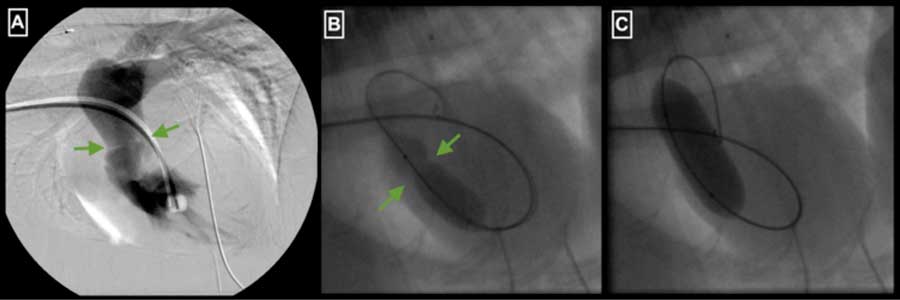

Balloon valvuloplasty was recommended and performed successfully for Toby (Figure 2), and a repeat echocardiogram one month later showed the stenosis had been reduced from severe to mild, resulting in an excellent long-term prognosis.