27 Oct 2020

Luca Motta uses the example of an eight‑month‑old bulldog to describe the diagnosis, therapy and prognosis for this issue.

Hydrocephalus can be defined broadly as an active distension of the ventricular system of the brain. Dogs with congenital hydrocephalus show clinical signs from birth or the first few months of life. Commonly, dogs with congenital hydrocephalus have a dome-shaped head, opened fontanelles, large calvarial defects and bilateral ventrolateral strabismus. The main clinical signs include obtundation, behavioural abnormalities, difficulty with training, decreased vision, blindness, circling, pacing and seizure activity.

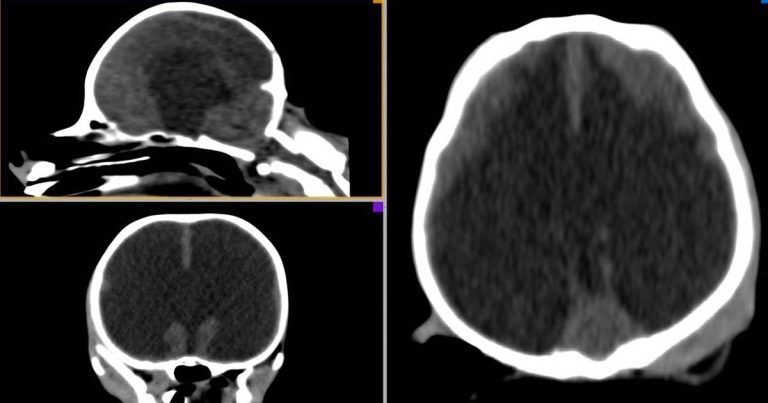

Diagnosis of hydrocephalus is usually made with the help of advanced imaging techniques (MRI and CT) that give information about the type of hydrocephalus and the hydrocephalus that requires treatment.

Therapy may be medical or surgical. Surgical treatment is generally recommended when an animal is showing worsening clinical signs, or shows no evidence of improvement or deteriorates when being treated medically. Medical therapy may stabilise or improve signs in the short term, but often it is not successful in the long term. A number of drugs (acetazolamide, furosemide, omeprazole, glucocorticoids, mannitol) may be used. In dogs, surgery is performed by placing a ventriculoperitoneal shunt. The overall prognosis after surgical therapy is guarded to good.

Hydrocephalus can be defined broadly as an active distension of the ventricular system of the brain.

Some breeds seem to be at higher risk of developing congenital hydrocephalus, including the Maltese, Yorkshire terrier, bulldog, Chihuahua, Lhasa apso, Pomeranian, toy poodle, cairn terrier, Boston terrier, pug and Pekingese.

Dogs with congenital hydrocephalus show clinical signs from birth or in the first few months of life, although (to complicate things) some animals may not develop neurological signs until adulthood.

Commonly, dogs with congenital hydrocephalus have dome-shaped heads, large calvarial defects, opened fontanelles and bilateral ventrolateral strabismus. The main clinical signs in dogs with congenital hydrocephalus include obtundation, behavioural abnormalities, difficulty with training, decreased vision, blindness, pacing, circling and seizure activity.

An eight-month-old male entire bulldog has been brought to your clinic as the client has noted that, over the past week, the dog started circling, pacing and having vision deficits (it would often bump into objects).

On neurological examination, you note the dog has a depressed mental status, is constantly circling to the right, has vestibular ataxia, does not have menace response bilaterally and often bumps into objects.

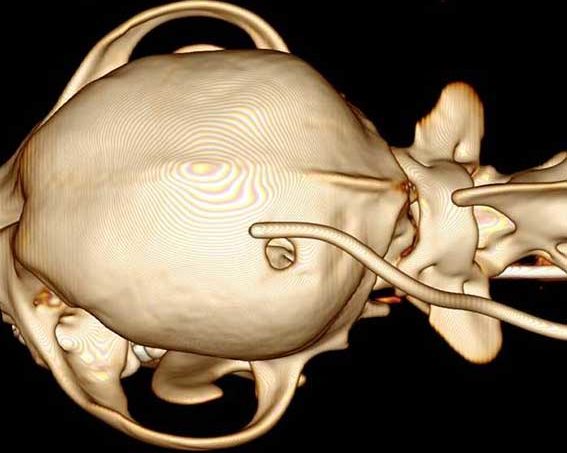

On physical examination, you note the dog has a mildly dome-shaped head and open fontanelles, and, because of this, you are suspicious that it has hydrocephalus.

The dog’s brain anatomy now needs exploring to confirm the presumptive diagnosis.

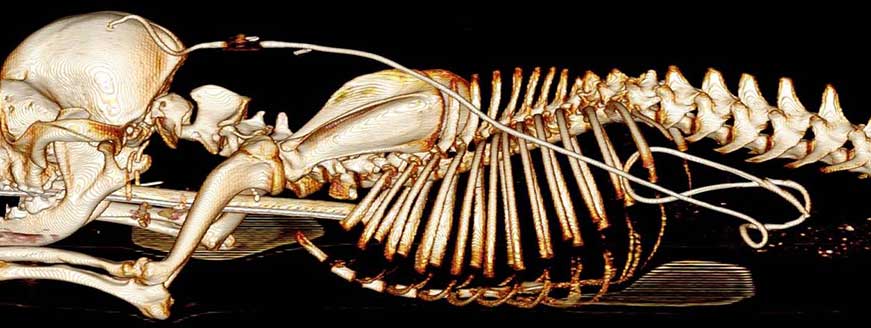

Diagnosis of hydrocephalus is usually made with the help of advanced imaging techniques (MRI and CT; Figures 1 to 3) that provide information about the type of hydrocephalus and the hydrocephalus that requires treatment. Ultrasound may help in some cases (Figure 4).

An MRI examination of the dog’s brain has revealed it has a markedly enlarged ventricular system. Can a diagnosis be made?

When reviewing advanced imaging pictures in dogs with suspected hydrocephalus, it must be remembered that ventriculomegaly and hydrocephalus are not synonymous; not all animals with ventriculomegaly have hydrocephalus. For example, asymmetric and symmetric enlargement of the lateral ventricles can be seen in neurologically normal dogs.

To correctly diagnose that the dog has clinically significant hydrocephalus, the signalment and clinical signs need combining to some specific features on imaging that can help support the diagnosis, such as:

Let’s say that by reviewing all these imaging parameters a diagnosis of clinically significant congenital hydrocephalus can be made. It’s time to plan the therapy.

Therapy for congenital hydrocephalus may be medical or surgical. To date, no clear outline describes when an animal should be treated surgically or medically.

Medical therapy can be started when surgery is not an option or while waiting for the surgery to be carried out. It can be useful to stabilise or improve clinical signs in the short term, but often it is not successful in the long term.

A number of drugs – acetazolamide, furosemide, omeprazole, glucocorticoids and mannitol – may be used, but their effectiveness in canine congenital hydrocephalus is doubtful.

A study (Kolecka et al, 2015) showed no significant differences in clinical signs and ventricle-brain ratio after therapy with acetazolamide at 10mg/kg three times daily.

The CSF production in healthy dogs may not be affected by chronic oral therapy with omeprazole (Girod et al, 2016).

Corticosteroids (0.25mg/kg to 0.5mg/kg twice daily) are commonly used for treatment of dogs with hydrocephalus as they may decrease the cerebral oedema and CSF production. A study (Gillespie et al, 2019) found 50% of dogs may positively respond to the corticosteroid therapy (median follow-up of nine months), whereas the other 50% of dogs medically treated deteriorate.

The usefulness of using furosemide and mannitol in dogs with clinically significant hydrocephalus is unknown.

The author recommends surgery in every case of clinically significant congenital hydrocephalus – especially when an animal shows worsening clinical signs and no improvement or deterioration after medical therapy.

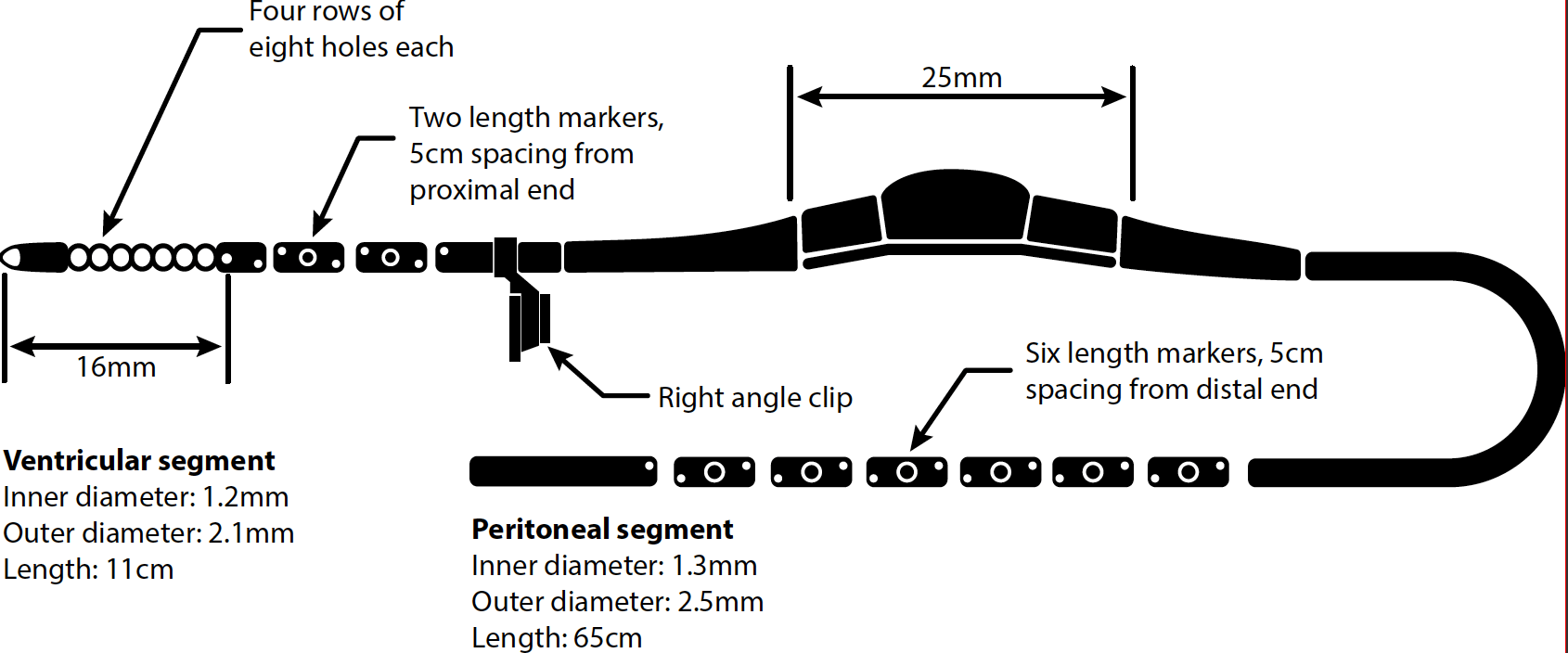

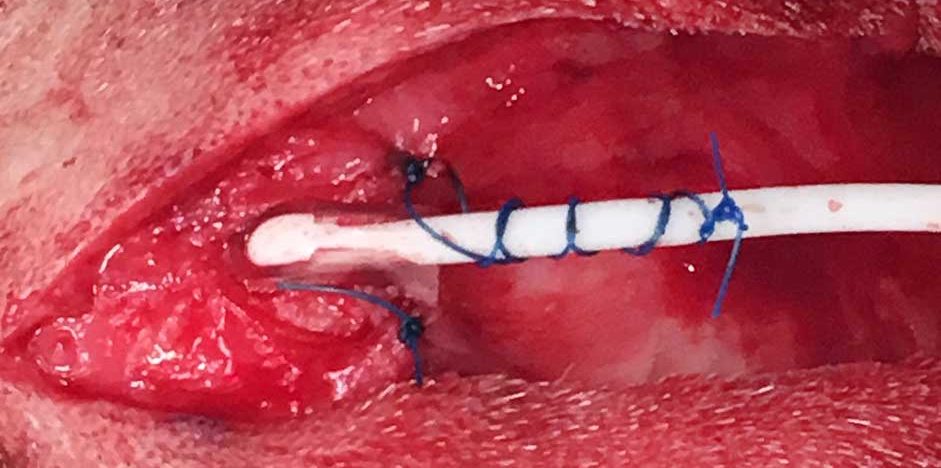

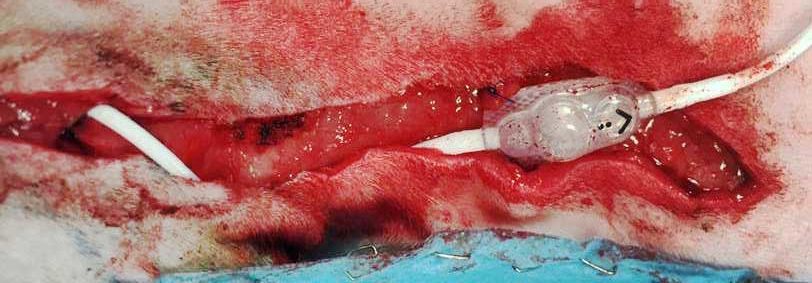

In dogs, surgery is performed by placing a ventriculoperitoneal shunt (VPS). The VPS consists of three parts:

The valve is a differential pressure valve – when the pressure difference increases above a set point, the valve opens to allow unidirectional movement of CSF from the ventricular system to the abdomen.

It is unknown which pressure valve is best to use in canine congenital hydrocephalus.

The aims of the surgery are multiple:

Most dogs tolerate the VPS surgery and show improvements postoperatively. However, approximately 20% to 30% of the animals may develop postoperative complications including shunt infections, blockage, overdrainage/underdrainage, breakage, migration, or disconnection of one or multiple components of the shunt (Figure 10).

Approximately 8% of dogs need shunt revision surgery because of postoperative complications.

The overall prognosis after surgical therapy is guarded to good. Long-term positive outcomes have been published – approximately 55% to 65% of dogs are alive 3.5 years to 9.5 years after the VPS surgery.

Overall, approximately 33% of dogs may die as a result of hydrocephalus-related complications or are euthanised because of lack of resolution of clinical signs or other causes unrelated to the VPS surgery. One study suggested most deaths and complications occur in the first three months after shunt placement.