22 Jul 2025

Canine otitis externa: reviewing available management options

Irina Matricoti DVM, DipECVD explores the current protocols for resolving infection and reducing the risk of relapse in dogs.

Image: Nynke / Adobe Stock

Otitis externa is a very common issue in dermatology patients and its prevalence is estimated to be up to 7.3% in general practice. Some studies reported that, in the canine population, up to two dogs out of 10 will suffer at least one episode of otitis in their lives.

Approaching cases of otitis externa can be frustrating for most clinicians and this is due to the complexity of its pathogenesis and the anatomy of ears in dogs.

Ears can have different morphology depending on the breed, with ears that can be pendulous or erect and might be rich in hair follicles or not. Moreover, some breeds, such as the cocker spaniel, have ear canals rich in glandular tissue, while brachycephalic breeds tend to have a narrow ear canal in its horizontal portion.

In the past few years, some studies have tried to identify specific factors that can be associated with otitis externa, and it was found that the retriever and cocker spaniel have an increased risk of developing otitis externa, while the Rhodesian ridgeback appears to be less frequently affected1,2. The reason can be easily implied for retrievers and cockers: these breeds – particularly retrievers – are often affected by allergic disease, which is an important primary cause of otitis externa, and cocker spaniels have pendulous ears, with ear canals rich in hairs and glands.

In particular conditions, hairs and hyperplastic glands can act as predisposing factors for otitis. The reason the Rhodesian ridgeback has, instead, a reduced risk to develop otitis externa is unknown; however, this data has been confirmed by two different studies.

To simplify management of otitis externa in dogs, it is important to rely on the “PSPP” approach. This approach implies that clinicians should always identify primary and secondary causes and predisposing and perpetuating factors3,4.

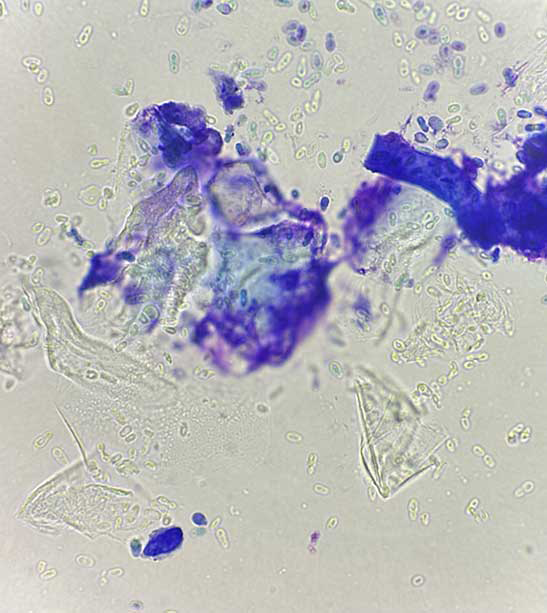

Primary causes are diseases that cause inflammation of ear canals and trigger otitis. Examples of primary causes are parasites or virus, allergic diseases, keratinisation defects (primary or secondary to endocrinopathy) or immune-mediated diseases (Figures 1 and 2).

Secondary causes are bacteria and yeasts that take advantage from a primary cause. The most important microorganisms living in the external ear canal of dogs are Malassezia pachydermatis, Staphylococcus pseudintermedius and Staphylococcus schleiferi. However, many other pathogens can be involved in otitis. Cytology of the ear canal is imperative in any case of otitis to identify secondary causes.

Predisposing factors are those conditions that increase the risk of developing otitis, namely the conformation of ear canals, the abundance of hairs and glands, the anatomy of the ear and skull in brachycephalic breeds or the presence of skin folds in the Shar Pei. Moreover, some habits such as frequently bathing the dog or inappropriately applying ear products can act as predisposing factors. Perpetuating factors are those conditions that prevent otitis resolution and lead to a progressive worsening of the disease. They are the result of pathological alterations induced by chronic inflammation and include stenosis of the ear canal due to epidermal and glandular hyperplasia, fibrosis, mineralisation of ear canal cartilages or otitis media (Figure 3).

All of these changes affect the normal epithelial cell migration. In normal conditions, cerumen, composed by superficial cells and glandular debris, migrates from the tympanic membrane to the external orifice to be expelled, as a “self-cleaning” mechanism. Inflammation – especially if chronic – alters this mechanism inducing cerumen accumulation and, consequently, bacteria or yeast overgrowth.

Clinicians should focus on identifying all these causes and factors to properly manage otitis externa. Unfortunately, some factors and causes cannot be corrected or cured definitively, and some kind of maintenance therapy may be prescribed to avoid relapses.

Management of otitis externa

One of the most frequent primary causes of otitis externa is atopic dermatitis, which is a chronic disease that causes inflammation.

Atopic dermatitis must be lifelong controlled to avoid flares and secondary ear and skin infections. In cases of otic disease (“atopic otitis”) not complicated by bacterial or yeast infection, patients are treated and maintained with topical steroids, such as hydrocortisone aceponate, administered on a regular basis (usually two consecutive days each week in the maintenance phase). Similarly, primary keratinisation defects usually require ceruminolytic or ceruminosolvent treatments to reduce cerumen accumulation in the ear canal.

Other factors that cannot be medically controlled are the anatomy of the ear canals and skull conformation. Usually, predisposing factors are not able to cause otitis themselves unless associated with a primary cause, although some exceptions exist4,5,6.

Secondary causes need to be identified by cytology and treated properly with the correct antimicrobial therapy. Bacterial culture is not routinely performed in cases of otitis externa as a first step. It must be performed when antibiotic systemic therapy is indicated (namely, concurrent otitis media or in cases of stenosis of the ear canal, which prevent the use of topical drugs).

The majority of ear infections are caused by M pachydermatis (Figure 4) and S pseudintermedius, which are normal components of the ear microbiota. These microbes take advantage by a primary cause (such inflammation due to allergies or cerumen accumulation due to other keratinisation defects), which favours their overgrowth. However, many other microorganisms can be involved in otitis externa.

In cases where cytology shows only mild microbial overgrowth, this is managed with only topical antiseptics, while topical antibiotics and/or antifungals are required in cases of moderate or severe ear infections.

Numerous topical preparations for the external ear canal are available on the market, with most being a combination of a glucocorticoid, an antibiotic and an antifungal. Polymyxin B, fusidic acid, florfenicol, gentamicin, enrofloxacin, marbofloxacin and orbifloxacin are suitable for most bacterial infections. Ticarcillin, polymyxin B, neomycin, tobramycin and amikacin are potentially ototoxic, and should be used with care if the tympanic membrane is damaged. Florfenicol and gentamicin are available in a long-acting topical otic product.

The European Medicines Agency has categorised antibiotics for veterinary use in four classes, and clinicians should prefer antibiotics in class D rather than antibiotics in class C and B, and avoid antibiotic in class A. The antifungal ingredients contained in the majority of otic products are polyenes (nystatin), azoles (miconazole, posaconazole, clotrimazole and so forth) or allylamines (terbinafine). Glucocorticoids found in ear drops range from more potent agents (mometasone, hydrocortisone aceponate, fluocinolone, dexamethasone and betamethasone) to relatively less potent drugs (triamcinolone acetonide and prednisolone).

The choice should be driven by the grade of inflammation of the ear canal and the risk of systemic absorption. With the exception of hydrocortisone aceponate and mometasone, all topical glucocorticoids may potentially cause adrenal suppression – especially when used for a long time.

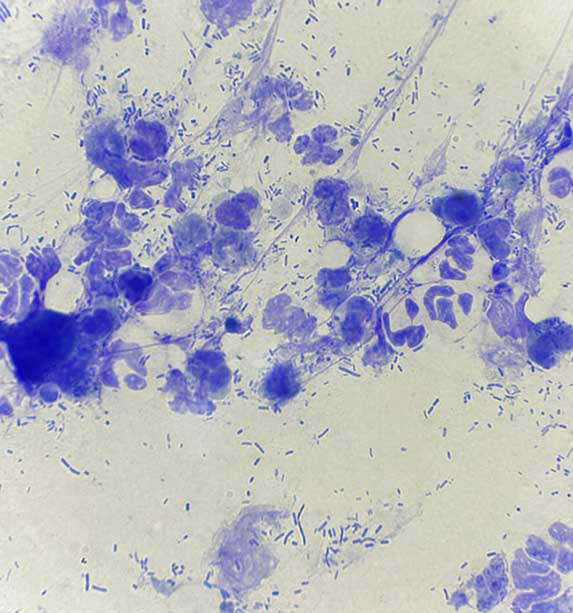

As previously mentioned, several types of bacteria can be involved in otitis externa, and Pseudomonas aeruginosa represents a challenge for most veterinarians (Figure 5). P aeruginosa is ubiquitous in soil and aqueous environments. In humans, otitis externa due to P aeruginosa has been linked to swimming in lakes, even with high-quality water. P aeruginosa has been isolated from multiple sites in the home, surfaces, water supplies and dishwasher rubber seals7. In the veterinary environment, P aeruginosa has been implicated with nosocomial infection and, regarding otitis, the risk of accidental inoculation using otoscopes not adequately cleaned should be avoided when performing otoscope examination. In fact, P aeruginosa can survive after disinfection of cones independently of the methods used (such as alcohol, wiping clean or speculum cleaner with disinfectant).

A survey evaluated the level of bacterial contamination of otoscope cones in veterinary private practice and found that 29% of the samples were contaminated with microorganisms, and contamination was associated due to a low frequency of storage solution replacement. Apparently, one of the best methods to sterilise cones is by soaking them in glutaraldehyde or chlorhexidine. In one study, a brand using the former was the most effective of the three most commonly used storage solutions in private practice8.

Pseudomonas species is often associated with biofilm formation, which consists of a microbial aggregate inserted in an extracellular polymeric substance. This extracellular substance is composed mainly of polysaccharides, proteins, nucleic acids and lipids, and creates a tridimensional network of bacteria. Cytologically, biofilm is suspected in the presence of aggregates of bacteria that are visible in different focal planes. Biofilm favours the sharing of resistance among bacteria, and in cases of Pseudomonas species infection, biofilm production and antimicrobial resistance are quite common. The most effective antibiotics, commercially available in cases of Pseudomonas species otitis externa, are quinolones (enrofloxacin, orbifloxacin and marbofloxacin) and aminoglycosides (in particular, gentamicin and polymyxin B). Some clinicians, however, use self-made preparations using dilution (in sodium chloride) of injectable antibiotics such as ticarcillin-clavulanic acid, amikacin or ceftazidime. These solutions might be beneficial in case the tympanic membrane is not intact. In cases where topical therapies are ineffective, bacterial culture should be performed before changing antibiotic. This test must be also performed in cases of otitis media and in general before prescribing systemic antibiotic therapy. Moreover, effective treatment of Pseudomonas species infection usually includes aggressive debridement and flushing of the ear canal (and middle ear, in cases of otitis media).

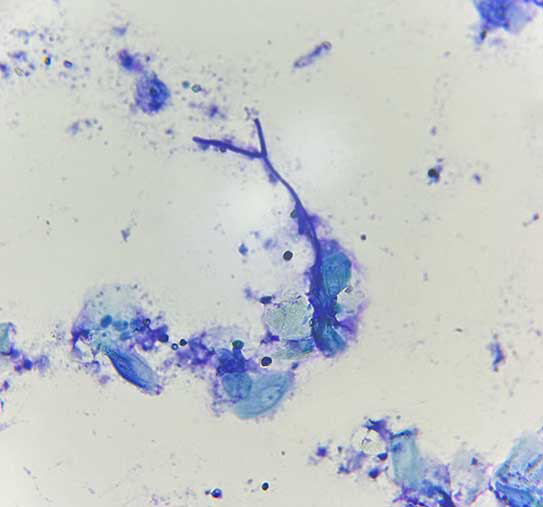

Another infrequent but frustrating cause of otitis externa, which should be considered in cases of poor responsive otitis, is Aspergillus species. Aspergillus species are a saprophytic environmental fungi, which occasionally causes opportunistic infections. The most common form of aspergillosis is the nasal sinus infection, and the German shepherd dog appears to be predisposed to more severe disseminated forms. Aspergillus species have been recognised as a possible cause of otitis externa (Figure 6). Large breed dogs with a history of immunosuppression or otic foreign bodies appear to be predisposed. The infection typically causes a brown ceruminous debris, and hyphae can be recognised cytologically. Treatment should include topical and systemic azoles and ear flushing. One study reported a mean time of resolution of 73 days9.

An important part of otitis management, independently from the type of infection, is the cleaning of ear canals. Cleaning is commonly prescribed at home using a commercially available cleanser, which usually includes ceruminolytics, surfactants, astringents, antimicrobials or other ingredients that disrupt biofilms. Several antiseptics are found in ear products, including isopropyl alcohol, aluminium hydroxide, chlorhexidine, iodine, parachlorometaxylenol, propylene glycol, sodium chlorite and sulphur. These agents are often combined with acids (acetic, boric, benzoic, lactic, malic, and salicylic acids) to lower the pH.

Antiseptics have the advantage of being broad spectrum, do not promote resistance to antibiotics and may have synergistic effects when used in combination with antibiotics. Tris-ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid (EDTA) disrupts the cell walls of Gram-negative bacteria, rendering the bacterial cell more porous, and inhibits the effects of bacterial enzymes. Tris-EDTA is useful in eliminating biofilm and might potentiate the action of some antibiotics (such as gentamicin, fluoroquinolones, silver sulphadiazine and chloramphenicol). N-acetyl cysteine, also found in association with tris-EDTA, acts against biofilm and is mucolytic. AMP2041, an antimicrobial peptide associated with tris-EDTA and chlorhexidine, works by disturbing and perforating the bacterial walls. The selection should be based on the type of ear infection; for example, tris-EDTA plus 0.15% chlorhexidine has showed some effect against P aeruginosa.

In cases of ceruminous otitis, ceruminolytics or ceruminosolvents, which usually contain squalene, dioctyl sodium sulfosuccinate, carbamide peroxide, propylene glycol, butylated hydroxytoluene or cocamidopropyl betaine should be preferred. Ceruminolytic/solvent products, with the exception of squalene, can cause ototoxicity in case of a non-intact tympanic membrane, and they should be flushed with saline solution when used in those circumstances.

To date, although ear cleanser/antiseptics are commonly prescribed as part of treatment, it is unclear what their benefit is in cases of otitis externa. A recent study aimed to determine if manual ear cleaning with a commercial cleanser prior to application of a commercial otic suspension would affect the treatment outcome.

In that study, dogs were divided into two groups and only one group performed a manual cleaning, using a commercially available otic cleanser containing several ingredients, among them 0.2% salicylic acid. As described by the authors, the cleaning was performed by filling the ear canal with the cleanser to the level of the external orifice and massaging the base of ear for 15 seconds, then letting the dog shake its head, and removing the excess cleanser with dry cotton ball or gauze. The procedure was repeated until obtaining a clean cotton ball. Cytology was performed before the procedure and on the seventh day, following a five-day course of otic treatment with ear suspension containing hydrocortisone aceponate, miconazole nitrate and gentamicin sulfate.

The study revealed a reduction in rod-shaped bacteria cytological scores from D0 to D7 compared to non-cleaned ears, while no difference was noted among the two groups regarding cocci or yeast. The authors concluded that ear cleaning may be particularly important when rod-shaped bacteria are present on cytological investigation10.

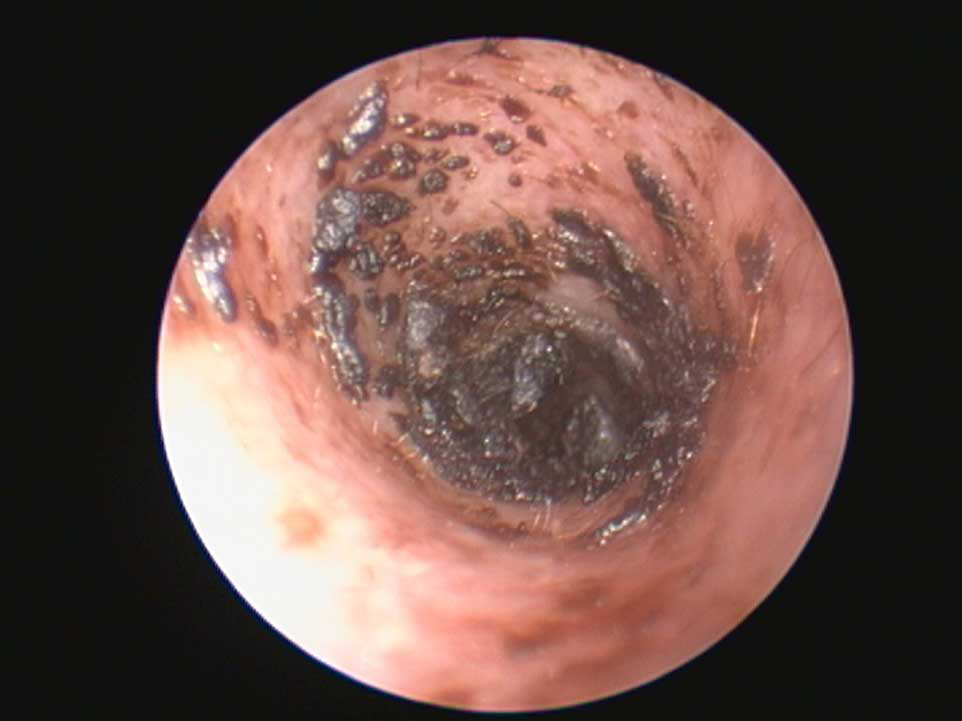

It is important to underline that sole cleaning at home might be ineffective – particularly in cases of chronic otitis when pus, debris and cerumen accumulate in the ear canals, often in the deepest horizontal portion and in the pre-tympanic area. For this reason, it is necessary to carry out an appropriate flushing and debridement on general anaesthesia, possibly through a video endoscopy (Figure 7). This procedure is also necessary to identify the condition of tympanic membrane. Moreover, some antibiotics (such as polymyxin B) have been reported to be inactivated by pus, and cleaning the ear is an important step before starting ear drops. Cerumen removal is also imperative in cases of refractory Malassezia species otitis externa.

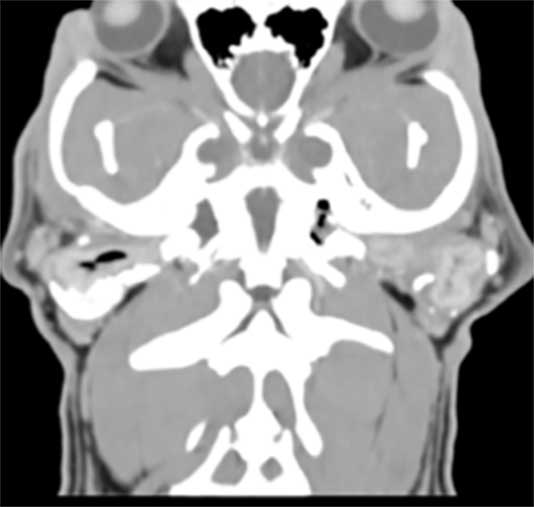

To manage chronic otitis, clinicians should pay particular attention to controlling perpetuating factors. Skin hyperplasia and stenosis of the ear canals is usually managed with systemic steroids. Treatment of these alterations may take months and, after a course of oral steroids, a switch to a pulse therapy with topicals (such as hydrocortisone aceponate, which is not absorbed systemically), administered generally two to three times a week, is often necessary for a longer management. Mineralisation and calcification, unfortunately, are very late modifications that cannot be reversed. Otitis media and other perpetuating factors may be a consequence of chronic otitis externa, and it should be investigated by means of tomography (Figure 8).

Moreover, chronic otitis can lead to another frustrating consequence, which is aural haematoma. It has been identified that the risk of developing aural haematoma increases with the age and the bodyweight of the patient. Moreover, some breeds appear to be predisposed, such as the French bulldog, English and Staffordshire bull terrier, golden retriever and St Bernard, and in general dogs with folded or semi-erect pinna. It has been postulated that in these breeds, pinna is more rigid at the fold of the cartilage and at the base of the pinna, and this favours the damage of the cartilage, consequently to chronic ear shaking.

Summarising, clinicians must be able to properly identify factors and causes involved in any case of otitis, and each of them should be addressed to obtain resolution of the infection and reduce the risk of relapse and possible consequences, which might be difficult to manage, such as otitis media and aural haematoma, which may cause frustration for most clinicians and owners.

- Use of some of the drugs in this article is under the veterinary medicine cascade.

- This article appeared in Vet Times (2025), Volume 55, Issue 29, Pages 6-12

For more on dermatology, visit the Vet Times clinical archive here.

Author

Irina Matricoti obtained her degree in 2008 from the University of Bologna. Afterwards, she worked in small animal practice and, during 2008-10, completed a postgraduate programme in veterinary cytology. Between 2016-19, she completed a residency programme in veterinary dermatology and became a European-certified specialist. Irina works as a dermatology specialist in private practice and at the Veterinary Teaching Hospital of the University of Bologna.

References

- 1. Ponn PC, Tipold A and Volk AV (2024). Can we minimize the risk of dogs developing canine otitis externa? – A retrospective study on 321 dogs, Animals 14(17): 2,537.

- 2. Ponn PC, Tipold A, Goericke-Pesch S and Volk AV (2025). Brachycephaly, ear anatomy, and co—does size matter? A retrospective study on the influence of size-dependent features regarding canine otitis externa, Animals 15(7): 933.

- 3. Miller WH, Griffin GE and Campbell KL (2013). Muller and Kirk’s Small Animal Dermatology, Elsevier, St Louis: 724-773.

- 4. Nuttall T (2016). Successful management of otitis externa, In Practice 38(S2): 17-21.

- 5. Paterson S (2016). Topical ear treatment–options, indications and limitations of current therapy, Journal of Small Animal Practice 57(12): 668-678.

- 6. Harvey R (2022). A review of recent developments in veterinary otology, Veterinary Sciences 9(4): 161.

- 7. Secker B, Shaw S and Atterbury RJ (2023). Pseudomonas spp. in canine otitis externa, Microorganisms 11(11): 2,650.

- 8. Kirby AL, Rosenkrantz WS, Ghubash RM et al (2010). Evaluation of otoscope cone disinfection techniques and contamination level in small animal private practice, Veterinary Dermatology 21(2): 175-183.

- 9. Goodale EC, Outerbridge CA and White SD (2016). Aspergillus otitis in small animals–a retrospective study of 17 cases, Veterinary Dermatology 27(1): 3-e2.

- 10. Corb E, Griffin CE, Bidot W et al (2024). Effect of ear cleaning on treatment outcome for canine otitis externa, Veterinary Dermatology 35(6): 716-725.