3 Jun 2025

Canine pyoderma: a common dermatological challenge

Karina Fresneda DVM, DiplACVP explores understanding, diagnosing and managing this familiar issue in dogs.

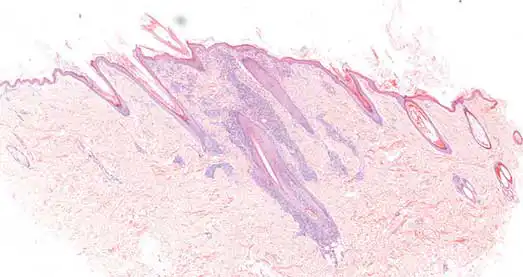

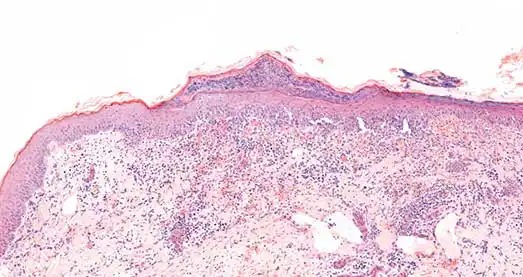

Figure 1. Skin. Superficial pyoderma. Focal pustule and superficial dermal chronic active inflammation.

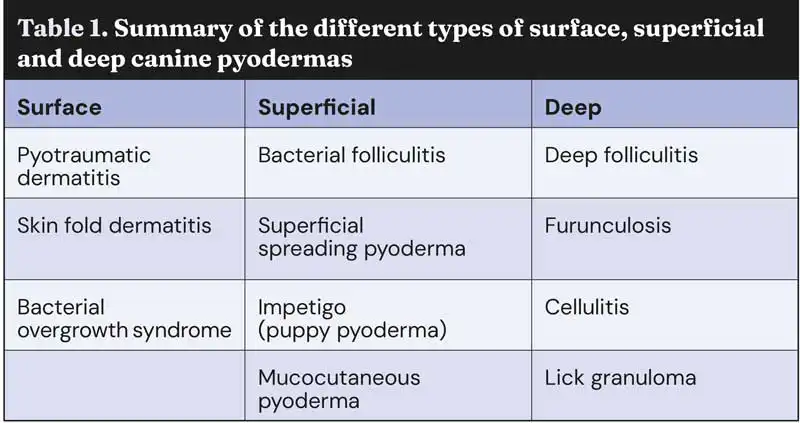

Canine pyoderma is a common bacterial skin infection predominantly caused by Staphylococcus pseudintermedius. Depending on the depth of infection, pyoderma can be classified as surface, superficial and deep (Table 1).

Lesion location and total area affected varies between patients and the specific type of pyoderma present. Each type of pyoderma can also be categorised as primary or secondary, the latter being most common.

Laboratory testing plays an essential role in differentiating other conditions from canine pyoderma, identifying underlying comorbidities in secondary cases, and determining which antimicrobials are effective against the infection.

With up to 92% of cases being prescribed systemic antimicrobial therapy (Summers et al, 2014) and the recent emergence of meticillin-resistant Staphylococcus pseudintermedius (MRSP; Bloom, 2014), an accurate diagnosis of canine pyoderma has become imperative for effective treatment and preventing antibiotic resistance.

Pathogenesis

Pyoderma is caused by a bacterial infection of the skin which causes an inflammatory reaction. The most common bacteria implicated in canine pyoderma is S pseudintermedius, which is a normal commensal bacterium of the skin.

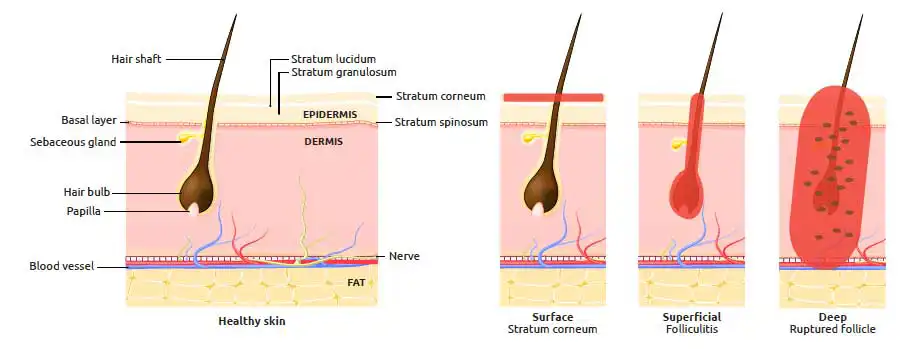

Canine skin can become infected with other Staphylococcus species such as S schleiferi, and other bacteria such as Escherichia coli and Pseudomonas aeruginosa, but this is less common (Bajwa, 2016). The depth of infection determines the classification for canine pyoderma (Figures 1 to 4).

Surface pyoderma is limited to the epidermis. Superficial pyoderma affects the epidermal layer of the skin, as well as the hair follicles.

Deep pyoderma involves the dermis, subcutis and hair follicles, and has the potential to cause a systemic bacteraemia. Demodicosis is commonly associated with deep pyoderma infections in dogs (O’Neill et al, 2020).

Primary canine pyoderma is seen less frequently and develops because of bacterial overgrowth on the skin, despite otherwise healthy skin (Tait, 2021).

Primary pyoderma is predominantly seen in immunocompromised patients. Meanwhile, secondary canine pyoderma is far more common, yet complex. Underlying pathologies interfere with the skin’s normal integrity and function, damaging the protective barrier.

Some of the common underlying causes include:

- Ectoparasites – demodicosis

- Allergic disease – atopic dermatitis, food allergies and flea allergic dermatitis.

- Poor grooming.

- Follicular dysplasias.

- Keratinisation disorders.

- Endocrine disease – hypothyroidism and hyperadrenocorticism.

Any condition that damages the skin barrier allows commensal bacteria to penetrate the skin, proliferate and elicit an inflammatory response. This results in a secondary bacterial infection (Tait, 2021). Damage to the skin barrier can either be intrinsic or through excoriation due to pruritus.

Clinical signs

Several dermatological lesions are associated with canine pyoderma. The lesions present will vary slightly depending on the classification of pyoderma and the severity of the patient’s condition. Surface pyoderma classically features erythematous, moist, ulcerated lesions with areas of alopecia.

Papules, pustules, crusts and epidermal collarettes are commonly seen in cases of superficial pyoderma. Recurring canine pyoderma may lead to chronic changes to the skin, such as lichenification and hyperpigmentation.

Deep pyoderma is more painful and features furuncles, nodules, haemorrhagic bullae and sinus tracts. Bacteraemia caused by deep pyoderma would result in systemic signs, such as pyrexia, anorexia, lethargy and sepsis.

Pruritus is variable depending on the exact type of canine pyoderma present.

Differential diagnosis

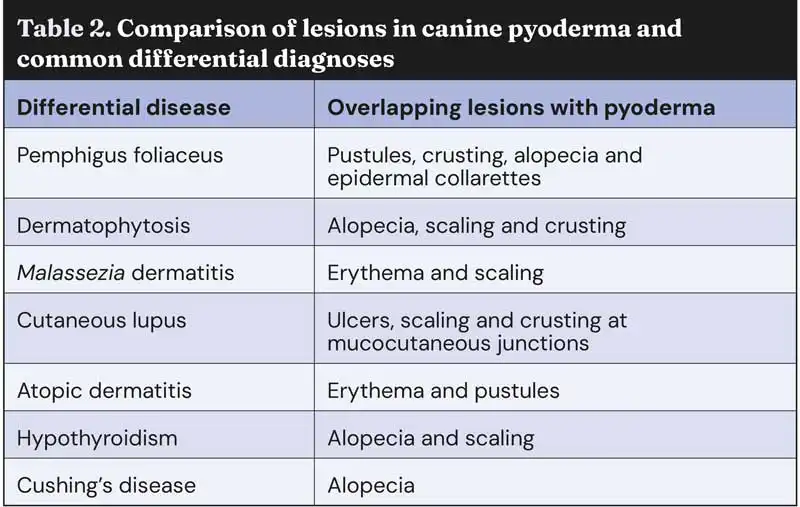

Many of the lesions mentioned previously are also seen in other dermatological, autoimmune and endocrine diseases (Table 2).

Ideally, a diagnosis of canine pyoderma should not be made based on clinical signs alone. The similarity in lesion presentation among these conditions highlights the need for additional diagnostic tests to accurately differentiate between them.

Cytology

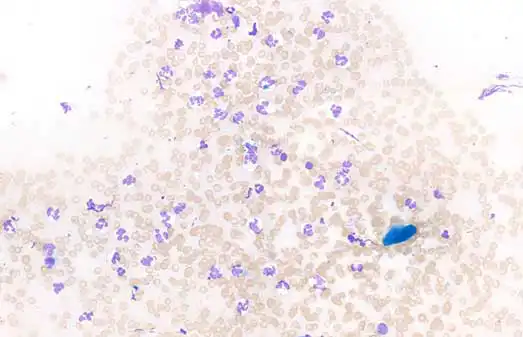

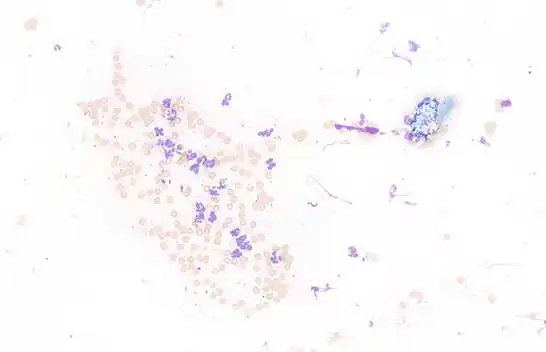

Prior to sending a pyoderma sample to the lab for culture, cytology should be performed to confirm the presence of bacteria. In-house cytology is cheap, quick and easy. The presence of neutrophils with intracellular bacteria would indicate a positive result for canine pyoderma with cytology (Figures 5 and 6). Cytology slides can be sent off for specialist interpretation by an external laboratory.

Histopathology

The typical histopathological findings in superficial pyoderma include neutrophilic infiltration of the epidermis (often forming pustules) and hair follicles, epidermal hyperplasia, and bacteria within the stratum corneum and/or within the pustules.

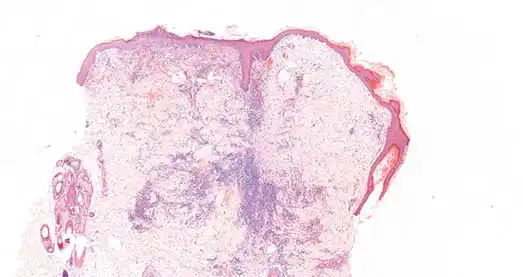

The findings for deep pyoderma include macrophage and neutrophil infiltration of the hair follicles, furunculosis, dermal fibrosis and haemorrhage. Accurately classifying pyoderma is crucial for devising an effective treatment plan.

Histopathology offers valuable diagnostic insights for recurrent and complex cases of canine pyoderma (Figure 7). It helps confirm classification, assess disease severity and chronicity, and differentiate it from other conditions; for example, the autoimmune disease pemphigus foliaceus can closely resemble canine pyoderma. However, histopathology reveals a unique feature of pemphigus foliaceus: acantholysis. This differentiation from pyoderma allows for targeted therapy (Goodale, 2019). Most importantly, histopathology aids in identifying underlying causes, which is crucial for effective long-term treatment of secondary pyoderma. Pyoderma can recur or become chronic if the underlying cause is not addressed, making it even more challenging to treat (Bajwa, 2016).

Culture and sensitivity

An ideal sample for culture is a lanced pustule with a sterile needle. Culture and sensitivity testing identifies the species of bacteria present in an individual case of canine pyoderma, and the antibiotics this strain of bacteria is sensitive to. This helps to select an appropriate and effective antibiotic as part of the treatment plan and is never contraindicated (Tait, 2021).

Recent concerns over MRSP warrant the use of culture and sensitivity testing to avoid further resistance (Bajwa, 2016).

Treatment

Treatment plans will depend on whether pyoderma is primary, secondary, surface, superficial or deep. Treatment aims to clear the bacterial infection based on the layer of the skin affected and address the underlying cause, if necessary.

Topical

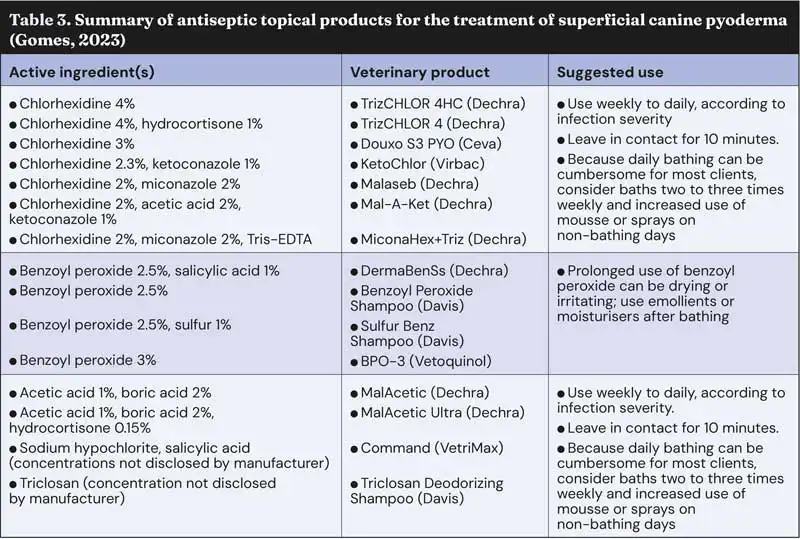

The mainstay treatment for surface and superficial canine pyoderma is topical therapy. The topical antiseptic chlorhexidine is recommended and comes in various formulations, including shampoo, wipes, sprays, and foams (Hillier et al, 2014). Other topical antiseptic ingredients include benzoyl peroxide, acetic acid, ethyl lactate, povidone iodine and triclosan (Gomes, 2023). The recommended use for these products varies slightly (Table 3).

Topical antibiotics, such as fusidic acid, can be effective in treating localised superficial lesions (Gomes, 2023) and should be prioritised instead of systemic antibiotic use. One study suggested that topical 4% chlorhexidine was as effective in treating superficial canine pyoderma as amoxicillin-clavulanic acid (Borio et al, 2015). This highlights the importance of prioritising topical treatments as a first-line option over systemic antibiotics. However, topical therapy relies much more on owner compliance, patient temperament and adequate administration (Gomes, 2023).

Revaluation of the patient should be performed after two weeks of topical therapy to determine treatment progress (Bajwa, 2016).

Systemic

For extensive, recurrent or deep pyodermas, systemic antimicrobial use may be warranted (Bajwa, 2016). However, studies have shown that systemic antibiotic dosing is often insufficient, and inappropriate antibiotic selection is a frequent issue. Prescribed daily doses should meet the minimum recommended daily dose and be given for an appropriate duration (Summers et al, 2014). Culture and sensitivity testing should be performed to select an effective antibiotic, preventing antimicrobial resistance.

Systemic therapy should be combined with the topical antimicrobial therapy mentioned previously (Bajwa, 2016).

Underlying disease

Addressing the underlying cause of secondary canine pyoderma is vital to prevent chronic and recurrent infections. Environmental allergies appear to be one of the most frequent primary causes responsible for recurrent pyoderma, followed by endocrine disease such as hypothyroidism (Seckerdieck and Mueller, 2018).

Signalment and diagnostic testing can help rule out different primary causes, enabling suitable treatment. Atopy and endocrine disease would benefit from allergy testing and blood testsm respectively.

Conclusion

Canine pyoderma is a common condition in veterinary practice and accounts for a significant number of antibiotic prescriptions.

Unidentified underlying causes and ineffective management lead to chronic and recurrent cases, negatively impacting canine welfare and the owner-vet relationship.

While topical therapies are recommended for surface and superficial pyoderma, factors such as cost, active ingredients, application frequency, patient temperament and owner compliance can limit their effectiveness. Identifying the primary cause in secondary pyoderma is essential to reducing the burden on owners. Diagnostic testing is crucial for accurate differentiation, identifying primary causes, and promoting good antibiotic stewardship. Histopathology helps distinguish pyoderma from conditions with similar lesions and identifies underlying issues in secondary pyoderma. Culture and sensitivity testing guide appropriate antibiotic selection, reducing resistance risks and ensuring effective treatment – particularly in deep and recurrent infections.

Utilising diagnostic laboratories provides an evidence-based approach, leading to more accurate diagnoses and better patient outcomes.

- Use of some of the drugs in this article is under the veterinary medicine cascade.

- This article appeared in Vet Times (2025), Volume 55, Issue 22, Pages 6-14

Karina Fresneda is a veterinary pathologist at NationWide Laboratories with extensive expertise in cytology and histopathology. She is a diplomate of the American College of Veterinary Pathology and graduated from the National University of the Centre of Buenos Aires Province in Argentina before specialising in anatomo-histopathological veterinary diagnosis, and underwent a three-year residency in anatomic veterinary pathology at the University of California. With more than 15 years’ teaching experience in infectious diseases, Karina has also contributed to clinical practice and laboratory work.

References

- Bajwa J (2016). Canine superficial pyoderma and therapeutic considerations, Can Vet J 57(2): 204-206.

- Bloom P (2014). Canine superficial bacterial folliculitis: current understanding of its etiology, diagnosis and treatment, Vet J 199(2): 217-222.

- Borio S et al (2015). Effectiveness of a combined (4% chlorhexidine digluconate shampoo and solution) protocol in MRS and non-MRS canine superficial pyoderma: a randomized, blinded, antibiotic-controlled study, Vet Dermatol 26(5): 339-344.

- Gomes P (2023). Topical treatment of canine superficial pyoderma, TVP, tinyurl.com/dvh3ct59

- Goodale E (2019). Pemphigus foliaceous, Can Vet J 60(3): 311-313.

- Hillier A et al (2014). Guidelines for the diagnosis and antimicrobial therapy of canine superficial bacterial folliculitis (Antimicrobial Guidelines Working Group of the International Society for Companion Animal Infectious Diseases), Vet Dermatol 25(3): 163-e43.

- O’Neill DG et al (2020). Juvenile-onset and adult-onset demodicosis in dogs in the UK: prevalence and breed associations, J Small Anim Pract 61(1): 32-41.

- Seckerdieck F and Mueller RS (2018). Recurrent pyoderma and its underlying primary diseases: a retrospective evaluation of 157 dogs, Vet Rec 182(15): 434.

- Summers JF et al (2014). Prescribing practices of primary-care veterinary practitioners in dogs diagnosed with bacterial pyoderma, BMC Vet Res 10: 240.

- Tait J (2021). Pyoderma in the dog, TVN, tinyurl.com/ympnvxbv