9 Sept 2025

Alex Brown DVM, MRCVS and Chris Linney BVSc, MSc, CertAVP(VC), DipECVIM-CA(Cardiology), FRCVS explain the importance of good communication with clients to help with spotting the signs, as well as treatment and management, of heart-related issues in pets

Image: CineLens/peopleimages.com / Adobe Stock

For most owners, a cardiac diagnosis comes as a shock. Whether it is an incidental murmur picked up at vaccination or sudden-onset dyspnoea in a previously healthy dog, the emotional weight can be heavy.

Their pet may still look outwardly well or, conversely, be in crisis; in both cases, the veterinary team is expected to provide clarity, support and direction quickly.

In this moment, trust starts with how we explain things. Using the right language, not oversimplified, but not overly technical, can shape how an owner feels. It does not take much: a pen and paper sketch, a simple analogy, or a moment spent framing the difference between “a murmur” and “heart failure” can make an outsize difference.

Trust is also shaped by transparency around cost and purpose. Most owners are not trying to avoid paying for care, they are trying to make sure the care is worthwhile. If we recommend an echocardiogram, we need to be ready to say: “This is the point at which we decide whether or not to start medication.” That is far more persuasive and reassuring than asking for tests without a clear explanation of how results will change management.

Not every owner wants the same level of involvement: some will ask for every detail; others just want to know what to do next; some would rather choose palliative care; some cannot afford referral; or some will not pursue advanced testing for other reasons. However, they all have pets in need of treatment, and offering non-judgemental support helps maintain engagement and makes it more likely that the patient will still receive appropriate care.

Owners want to know that we will explain what matters, follow through on our plans, and be honest when the path ahead is uncertain. In cardiology, where management is often long term, this kind of practical, consistent communication sets the tone for everything that follows.

Cardiac disease often demands long-term engagement, regular monitoring and nuanced management, none of which can succeed without an active, communicative partnership between vets and pet owners.

Owners are often the first to notice when something changes. Subtle signs such as reduced stamina, altered sleeping posture, or shifts in breathing may appear well before clinical disease becomes obvious.

Encouraging early reporting of these signs can shift the diagnostic timeline and improve outcomes.

Resting respiratory rate is a particularly valuable tool for home monitoring. With minimal training, most owners can reliably track their dog’s sleeping rate, often detecting early signs of decompensation before more serious symptoms arise. In this way, owners become a vital part of the clinical team.

Resting respiratory rates of less than 30bpm in the dog and less than 40bpm in the cat would be consistent with normal findings or controlled congestive heart failure1.

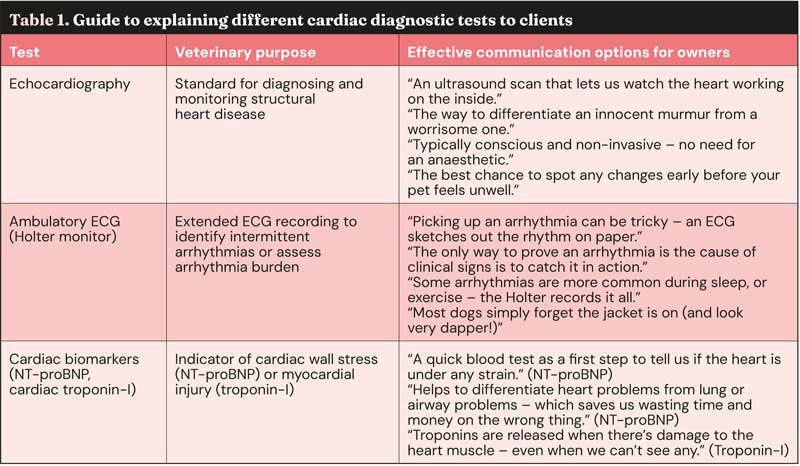

From echocardiography and ECGs to Holter monitoring and N-terminal pro-B-type natriuretic peptide (NT-proBNP) testing, cardiac diagnostics are essential yet unfamiliar for many owners.

Clearly explaining what each test does and how it guides treatment helps foster trust and avoid confusion. Owners appreciate knowing not just what a test will show, but what it will change (Table 1). That clarity is especially important when costs are a concern.

Honest, case-specific conversations help owners feel informed and supported in their decision making.

Some owners want regular heart scans and detailed involvement, others prefer to keep things simple and trust us to guide them – neither is wrong. Our role is to understand where each client sits and adjust the approach accordingly.

For some, reassurance comes from frequent monitoring, even when treatment stays the same. Others may opt for fewer interventions if no immediate therapeutic benefit occurs. Early, regular contact via phone, email, or brief follow ups can be especially helpful post-diagnosis, when things are still settling.

A nurse-led clinic or telephone check in can really help to manage heart disease well and closely, continuing the patient-owner-veterinary clinic bond.

Owners bring different values and expectations to treatment. For some, the goal is to extend life; for others, it is to maintain a good life for as long as possible, even if that means less time overall.

This may mean not treating for particular risks such as medicating with an anti-thrombotic due to palatability issues in some feline patients.

This matters when discussing lifestyle modifications. In arrhythmogenic conditions, reducing intense activity may lower the risk of sudden death, but for some dogs, ball games are their greatest joy. When clients understand the risks and make informed choices, our job is to support those decisions, not override them.

As disease progresses, small changes at home such as altering routines, avoiding heat and tweaking walk duration can all make a big difference. Most owners are willing to adapt – especially when they understand why it helps. It is about offering simple, achievable suggestions with clear explanations, tailored to their pet and their life.

Degenerative mitral valve disease (DMVD) is the most common acquired cardiac condition in dogs and a clear example of how owner–vet collaboration shapes outcomes.

Large-scale primary care data from England estimate the prevalence of DMVD at around 3.5% of practice-attending dogs, though much higher rates are seen in predisposed breeds such as the cavalier King Charles spaniel, where almost all are affected by 10 years of age2. The disease often progresses silently over years, with no obvious signs until congestive heart failure develops. While that slow progression can be clinically fortunate, it can also risk owners disengaging – especially when their dog seems healthy.

A critical turning point comes with the transition from stage B1 (minimal cardiac remodelling) to stage B2 (evidence of left atrial and left ventricular dilation). This shift is not visible to owners, but marks the point where starting pimobendan can meaningfully delay the onset of clinical signs by 15 months3.

Helping owners understand that these scans are not generic “check-ups”, but targeted opportunities to detect a key moment for intervention, can improve their understanding and acceptance.

It is also reassuring for owners to hear that once a dog starts treatment at stage B2, echocardiogram frequency often decreases, as scans may no longer drive immediate changes in care.

At this stage, resting respiratory rate (RRR) becomes an invaluable tool. Teaching owners to measure RRR during sleep empowers them to detect early pulmonary oedema and reinforces their role in the care team. Still, in long B1 phases, owners may become complacent.

Regular, gentle reinforcement of why consistency matters through regular reviews, even when things appear stable, can help maintain engagement.

In larger breeds such as the Dobermann and boxer, dilated cardiomyopathy (DCM) and arrhythmogenic right ventricular cardiomyopathy often remain silent until they manifest as arrhythmias, syncope, or heart failure. Early changes such as reduced systolic function or ventricular ectopy are detectable only via echocardiography or Holter monitoring, often well before any clinical signs may appear4.

Understandably, some owners are sceptical about the need for costly screening tests when their dog seems perfectly well. But explaining the potential to identify disease before symptoms and, in some cases, extend life with early intervention5, can help frame the value of screening in practical, rather than abstract, terms.

Lifestyle modification is often the most difficult conversation. Dogs with ventricular arrhythmias or advanced DCM are at increased risk of sudden cardiac death during periods of excitement or exertion.

Asking owners to restrict high-arousal activities such as fetch or off-lead running can be emotionally challenging, as these are often the moments that bring dogs their greatest joy. A balance between science and quality of life must be maintained, with contextualised care taking both owner and patient needs into account.

Some owners are willing to trade activity for safety, others are not. Our job is not to impose, but to explain the risks clearly and support them in making the decision that feels right for them and their dog.

This is true shared decision making: evidence, experience and values coming together to shape care.

Cardiac disease in cats brings its own complexities, both in diagnosis and management. Hypertrophic cardiomyopathy is the most common condition6, but it may go undetected until a thromboembolic event or sudden death occurs.

Screening via auscultation, NT-proBNP testing or echocardiography can help identify at-risk individuals – especially in predisposed breeds such as the Sphynx, Maine coon and ragdoll. However, routine monitoring and reassessment are often limited by feline tolerance and stress.

One key point of collaboration is deciding when to initiate anti-thrombotic therapy. We typically look for risk factors such as left atrial enlargement, reduced atrial function, presence of spontaneous echocontrast or decreased auricular appendage flow velocity parameters that require an echo to assess7.

For some cats, regular scans are simply not an option, and that becomes part of the treatment decision.

Even when medication is warranted, treatment is not always straightforward. Clopidogrel has typically been used as the first-line antiplatelet medication, but for many cats the taste is bitter and poorly palatable. Administering it daily can be a significant source of stress (and frothy saliva) for cats and owners alike.

In these cases, we must weigh the theoretical benefit of clot prevention against the potential cost: food aversion, chronic stress and a strain on the human–animal bond.

Thankfully, recent evidence suggests that rivaroxaban, a factor Xa inhibitor, is equally effective for prevention of recurrent arterial thromboembolism, and this offers another option for those tricky feline customers. The decision to start anti-thrombotics prior to the development of a thrombus (such as primary thromboprophylaxis) has also not been proven, and the current data set is in cases that have already had a thromboembolic event8,9.

A similar challenge arises in managing dynamic left ventricular outflow tract obstruction (LVOTO). This is often observed only during the stress of a consult and may not be present at home. While beta blockers may be prescribed, evidence for a clear survival benefit is lacking10; although, for those that develop symptoms associated with exertion and LVOTO such as chest pain – a challenge to assess in feline patients – some relief may arise from reducing the degree of LVOTO. For some owners, the possibility of improvement is worth the effort; for others, the daily battle of medicating a reluctant cat with no guaranteed outcome does not feel justified.

As with any chronic condition, care must be individualised. Cats are not small dogs, and cat owners are definitely not small dog owners.

When a case is referred for specialist input, it is easy for clients to feel that everything has been “sorted.” But real long-term success depends on a shared, ongoing approach.

Together, the primary care clinician and referral clinician work hard to ensure that the comprehensive, detailed discharge summaries and update letters provide not only a summary of the visit, but also the next steps to be carried out in the most convenient and familiar setting for the client, that of their local and trusted practice. Owners commonly travel long distances for specialist input, and many follow-up needs such as a routine blood test after a diuretic dose adjustment, or blood pressure assessment, can be managed effectively in general practice.

This not only makes care more accessible, but reinforces the idea that the whole team is working toward a single goal: the well-being of the patient.

Some cases will continue under shared care for years. A patient with mitral valve disease might be seen annually for echo reassessment, while interim blood tests, blood pressure checks or diuretic dose adjustments are managed locally. Even small tasks such as checking electrolytes after a medication change become meaningful contributions to a broader plan. This collaborative approach does not just improve continuity; it also helps distribute the workload realistically between what needs specialist input and what does not. It is also important to remember that not all cardiac care is about chronic disease. Some of the most impactful interventions occur early in life.

Minimally invasive cardiac procedures such as patent ductus arteriosus occlusion or balloon valvuloplasty can offer curative or long-term positive outcomes for congenital defects in puppies and kittens. These cases often rely on early detection in general practice, and timely referral can change the entire trajectory of that animal’s health.

Good communication between primary care and referral clinicians makes this possible, allowing us to act decisively while the window for intervention is still open.

Finally, when we think about teamwork, it is worth remembering that good coordination is not about standardisation; it is about adaptability.

Not every owner will need the same intensity of contact. Not every practice has the same resources. But by building flexible, honest communication channels between the referral centre, primary care clinician and their team, and the owner, we create a more resilient, responsive model of care, and one that is capable of meeting the needs of all of our different patients.

Alex Brown is a cardiology resident at Paragon Veterinary Referrals, Yorkshire. He graduated from Trakia University, Bulgaria, in 2021 before returning to the UK to work in small animal general practice. In 2023, Alex joined Paragon, completing a rotating internship before moving into a cardiology internship, followed by a three-year European College of Veterinary Internal Medicine residency programme in small animal cardiology.

Chris Linney is an RCVS Specialist in Small Animal Cardiology and clinical lead of the cardiology service at Paragon Veterinary Referrals, Yorkshire. He graduated with honours from the University of Liverpool in 2007, where he later completed an internship, residency and lectureship in cardiology. He also undertook advanced training in human interventional cardiology, becoming the first veterinary cardiology specialist worldwide to gain a master of science in the subject. Chris went on to establish one of the busiest interventional cardiology services in the UK, and was recently awarded Fellowship of the RCVS for his contribution to clinical practice. He lectures widely and is recognised internationally for his expertise in minimally invasive cardiac procedures.