4 Jul 2022

In the fifth and final part of this series, Gerardo Poli turns to advanced life support and discusses vasopressors and vagolytic agents, both of which are widely used in veterinary CPR.

Advanced life support (ALS) can only be initiated once basic life support (BLS) has commenced.

Where BLS refers to the initial stages of intubation, ventilation and chest compression, ALS is the advanced stage where vasopressors, positive inotropes, anticholinergics, correction of electrolyte disturbances, volume deficits, severe anaemia and defibrillation are performed.

This is an important aspect of the cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR) process, as the return of spontaneous circulation (ROSC) rates can reach up to 50% in dogs and cats if both BLS and ALS are commenced promptly.

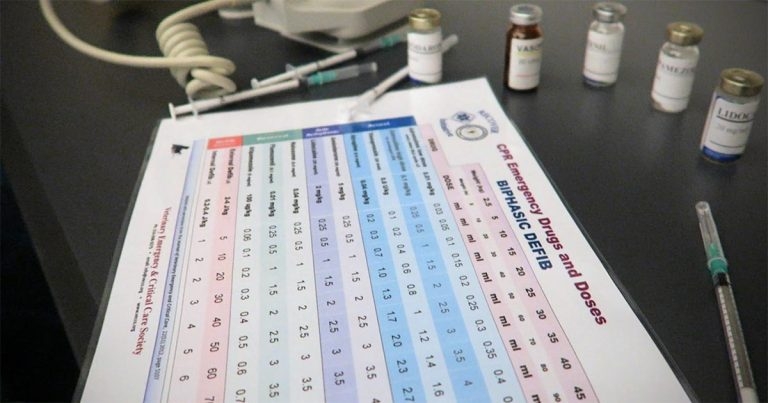

Vasopressors and vagolytic agents are widely used in veterinary CPR and crucial in the success of ROSC. The most commonly used agents include epinephrine, vasopressin and atropine.

The ultimate aim of CPR is to restore myocardial function. The myocardial arteries stem from the coronary arteries; thus, the coronary perfusion pressure (CPP) is a surrogate indicator of myocardial perfusion.

CPP is defined as the difference between diastolic aortic and right atrial pressure – hence, the higher the diastolic aortic pressure, the higher the CPP. Vasopressors increase this diastolic aortic pressure by diverting the peripheral circulating volume to the central circulation via the actions of peripheral vascular resistance.

Certain vasopressors, such as catecholamines, also possess inotropic and chronotropic properties. These, although theoretically beneficial, can be clinically detrimental, as they increase myocardial oxygen consumption, exacerbate myocardial ischaemia and predispose the heart to arrhythmia once ROSC is attained. In fact, high doses of epinephrine (0.1mg/kg) are associated with severe tachycardia and hypertension after resuscitation, and did not improve 24-hour survival and neurological outcome in humans1,2.

No controlled veterinary studies exist of high-dose versus low-dose epinephrine in veterinary patients. Extrapolation from human data prompted the current recommended dosage in cats of 0.01mg/kg IV, which can be repeated every three to five minutes as required.

Vasopressin, or antidiuretic hormone, is a non-adrenergic vasopressor responsive in acidotic and hypoxic environments. It appears to be a reasonable agent to use during CPR, although the evidence from veterinary studies is limited.

The only prospective canine clinical trial showed no difference in ROSC between dogs receiving vasopressin or epinephrine. In human literature, a possible advantage exists of vasopressin in resuscitating humans, but only in subgroups of patients with asystole, prolonged CPA or with hypovolaemia as a cause of CPA.

The current recommendation for vasopressin to be used at 0.8U/kg IV in combination, or alternate, with epinephrine in every second two-minute cycle of CPR.

The role of vagolytic agents in CPR appears to be limited. Atropine, an anticholinergic parasympatholytic agent, exerts its action by counteracting bradycardia or sinus arrest caused by high vagal tone – for example, vomiting and ileus. Due to this mode of action, its use as the sole agent in most CPA cases is limited. It is, however, a reasonable additional agent to epinephrine.

In a comparative study into the resuscitation of dogs with pulseless electrical activity (PEA), using epinephrine with atropine or 5% dextrose in water, the dogs receiving atropine were more likely to have ROSC3. An experimental study has also noted dogs with hypoxia-induced PEA had worse outcome when resuscitated with atropine at higher-than-standard doses (0.04mg/kg)4.

Therefore, the current recommendation is to give atropine as an additional agent to epinephrine in every alternate two-minute cycle.

Epinephrine will continue to play a crucial role in ALS in veterinary CPR. Vasopressin and atropine, on the other hand, can be used in addition to epinephrine, but never in lieu of.

Further studies are required to establish their roles in CPR before further recommendations can be given.

Gerardo Poli

Job Title