24 Aug 2025

Kate Parkinson BVSc, MRCVS recounts an interesting case where a wooden stick was discovered in a patient, and weighs up the benefits of different imaging techniques.

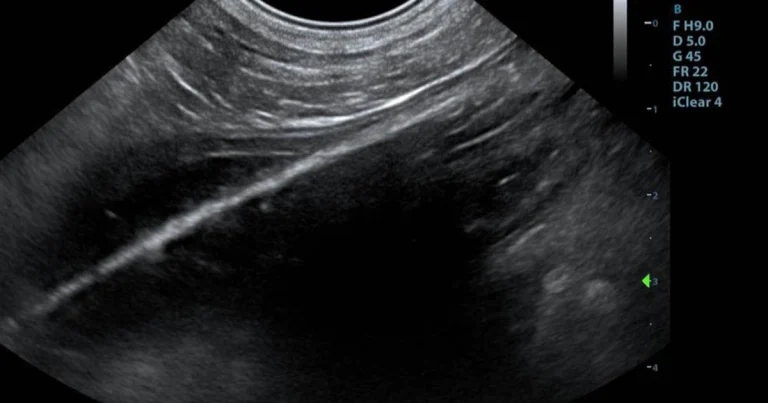

Figure 1. Ultrasound image of the foreign body.

An 11-year-old male neutered poodle presented as an emergency out of hours for vomiting and shaking. The dog had been walked at a popular local park half an hour previously and had begun to show symptoms on returning from the walk.

Although the dog had been off lead during the walk, the owner had not noticed it ingesting anything unusual. The dog had vomited twice, but no obvious toxin was visible in the fluid.

During initial emergency presentation, a toxicity was suspected. The dog, which normally had a healthy appetite, was still eating and passing faeces.

The patient was 11 years old with no previous history of foreign body ingestion and was considered a relatively low risk for a foreign body, according to the history gained from the owner.

The dog had previously been referred to the presenting clinic for an abdominal ultrasound in June of the previous year. The initial scan showed a potential gastric ulcer, but repeat ultrasonography found the ulcer had disappeared.

The owner mentioned that the dog had been referred to a different clinic many years previously to investigate persistent vomiting and underwent an exploratory laparotomy, with no foreign body found. Pancreatitis was thought to have been diagnosed, but no history was available.

On presentation, the dog was bright, but its owner reported it was more subdued than usual in the clinic.

The dog was tachycardic with a heart rate of 160bpm and pyrexia, with a temperature of 39.5°C. The dog’s mucous membranes were pink and moist, with a capillary refill time of less than two seconds. No neurological abnormalities were detected on clinical exam.

The dog was drooling, but no abnormalities were found upon oral exam. The cranial abdomen felt tense on initial examination, but on repeated palpation seemed more relaxed.

Rectal examination revealed a foul-smelling brown stool. The patient was admitted and a blood sample was taken for analysis. The patient was hospitalised on intravenous fluids (lactated Ringer’s, 5ml/kg/hr) and a FAST scan was performed, which was unremarkable.

Blood results revealed a mild lymphopaenia and a slightly raised alkaline phosphatase.

Within an hour of admission, the dog’s temperature had increased to 39.9°C and its heart rate had reduced to 120bpm. Paracetamol was given (10mg/kg slow IV). The patient was hospitalised overnight.

The following morning, the dog was brighter and had not vomited. The abdomen was relaxed and appeared non-painful. The patient ate and passed urine and faeces. The abdomen was comfortable, although the dog’s heart rate was 148bpm and temperature was 39.5°C.

Urinalysis was performed and was normal, except for the specific gravity that had reduced to 1.010 following fluids. A canine pancreatic lipase test was weakly positive.

After discussion with the owner, the decision was made to perform further diagnostic imaging to investigate the cause of the dog’s persistent pyrexia and tachycardia.

The patient was very compliant, and an abdominal ultrasound exam was performed without sedation. Ultrasonography revealed small pockets of free fluid in the abdomen at the bladder neck and central ventral abdomen. The fat throughout the abdomen had increased echogenicity.

An opacity was visible in the lumen of the jejunum. This object presented as a perfectly straight echogenic line, which did not change shape regardless of probe angle or pressure (Figure 1).

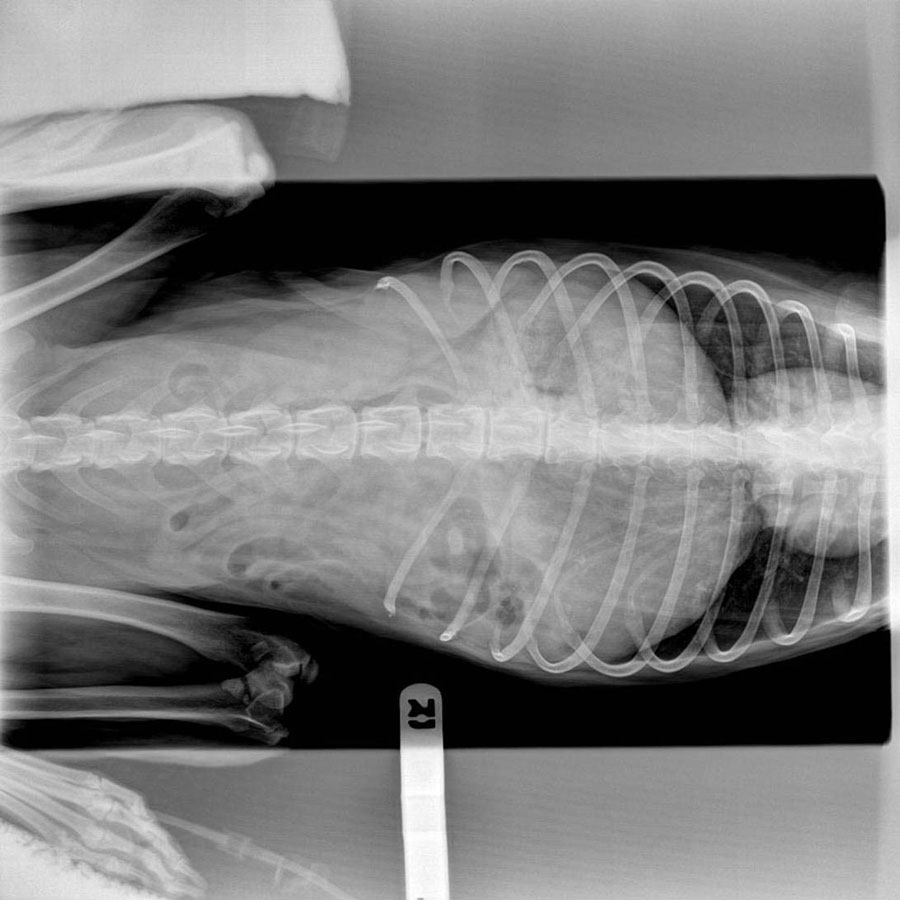

Radiography of the thorax and abdomen was normal, with no evidence of a radio-opaque foreign body or free fluid or gas in the abdomen (Figures 2 and 3).

A small intestinal foreign body was suspected, with concerns of secondary peritonitis.

Exploratory laparotomy was recommended to the owner. An estimate was given, potential complications discussed and consent gained for surgery.

A premedication of methadone 0.2mg/kg (0.4ml) and midazolam 0.3mg/kg (1.2ml) IV was administered. The dog was induced with propofol IV to effect, intubated and maintained on inhalation anaesthesia of isoflurane and oxygen.

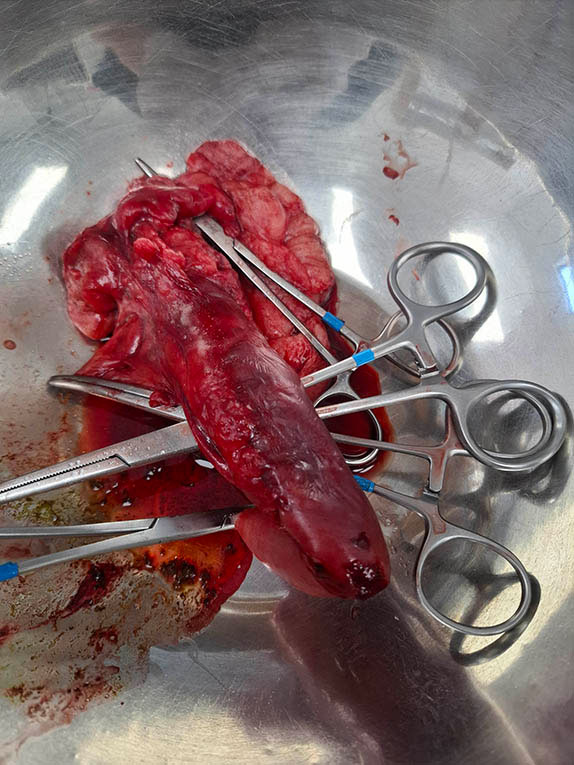

A midline incision was made. The dog had intestinal adhesions, presumably caused by his previous abdominal surgery. Three loops of jejunum were adhered together and attached to the falciform ligament. A firm, rigid foreign body was palpated in the patient’s jejunum, with the cranial end of the obstruction lodged in the most caudal adhesion, which was in turn adhered to falciform fat. The intestinal serosa was damaged and heavily bruised, though not yet ruptured, and the mucosa was torn.

The adhesions were gently broken down by manual pressure and a jejunotomy was performed (Figure 4). Following jejunotomy, the abdomen was lavaged with 500ml sterile saline and the rest of the abdominal organs were examined, with no other abnormalities detected. The jejunotomy site was omentalised and the abdominal wound was conventionally closed.

On removal, the foreign body proved to be a blunt-ended stick, approximately 17cm long, similar to a giant popsicle stick (Figure 5). The stick may have had food attached at some point, making it attractive to ingest.

Post-surgery, the patient made a complete and unremarkable recovery.

The day following surgery, the dog attempted to eat a stone in the car park during a walk, but was prevented from swallowing the stone by a vigilant nurse. The chance of a repeat foreign body was discussed with the owner, and close future observation was advised.

Three months post-surgery, the patient remains clinically well (Figure 6).

Although foreign body ingestion is a very common cause of vomiting in dogs, this case was interesting, as the foreign body was detected very easily on ultrasonography, but was not palpable on clinical exam or visible on radiography.

Traditionally, plain radiographs have long been the initial screening test for suspected foreign bodies1.

However, in a recent study comparing radiographs with ultrasonography in cases of small intestinal obstruction in dogs, it was found that a definitive diagnosis was possible using radiographs in 70% of cases2 based on a radio-opaque foreign body, evidence of plication or small intestinal dilatation.

Ultrasonography produced a result in 97% of dogs, again based on detection of a foreign body (as in this case), sonographic signs of plication or a small intestinal dilatation. In another study, ultrasonography detected a foreign body in 100% of animals3, though ultrasonography is notoriously operator dependent4.

This indicates that although both radiography and ultrasonography are useful in diagnosing small intestinal obstruction in vomiting dogs, in the right hands, abdominal ultrasonography may be used with greater diagnostic confidence than radiography.

Abdominal ultrasound may also be more useful in diagnosing ileus and evaluating gut motility. It is also the treatment of choice for diagnosing intussusception5. In most cases, the use of abdominal ultrasound has superseded the use of barium sulfate or barium-impregnant polyethylene spheres (BIPS) in contrast studies, as ileus can prevent contrast medium reaching the site of obstruction and delay the passage of contrast medium through the intestines. Avoiding barium reduced the risk of regurgitation of barium and potential aspiration or inhalation of barium-impregnated stomach contents.

In addition, linear foreign bodies may also be more easily detected on ultrasonography, with a typical accordion-like appearance in longitudinal sections5, as is the characteristic multiple concentric rings in transverse sections of an intussusception. Mechanical blockages caused by intestinal masses, such as neoplasia, are also relatively easily detected with ultrasonography, as compared to ultrasound.

In cases of mechanical obstruction of the small intestine, dilated fluid-filled intestinal loops with increased or decreased activity are often seen.

The appearance of intestinal foreign bodies varies depending on their acoustic impedance. Foreign bodies that produce strong acoustic shadowing may be more easily visible. Wooden foreign bodies, such as this one, often present as a linear echogenic structure with pronounced acoustic shadowing6.

Ultrasonography is widely used to detect wooden foreign bodies in human medicine.

In one study, it was shown that only 15% of wooden foreign bodies were detected using radiography, while in a small study of 20 human patients, all of the wooden foreign bodies recovered were missed by radiography7.

The main limitation of abdominal ultrasonography is that is heavily operator dependent – especially in countries with limited access to experienced operators or referral centres. In such situations, radiography is generally cheaper and more readily available. Radio-opaque foreign bodies and complete intestinal blockages causing gas dilation are easily detected by radiography, while radiolucent foreign bodies such as socks, corn cobs, sticks (as in this case), fruit stones and plastic toys – especially those causing a partial blockage – can be much more difficult to detect.

CT examination may be useful in the detection of wooden foreign bodies. Although considerably more expensive than ultrasonography, CT is less expensive, more readily available and faster to perform compared to MRI6, though may be out of reach of many first opinion veterinary practitioners.

Wooden foreign bodies are often hard to detect using MRI, although the inflammatory response may sometimes be identified6.

In conclusion, abdominal ultrasonography was vital in the diagnosis and subsequent successful surgical outcome in this patient.

Radiolucent foreign bodies causing partial blockages of the gastrointestinal tract can be notoriously difficult to detect on radiography, but may be relatively easily detected with ultrasonography.

Abdominal ultrasonography is also the modality of choice when detecting linear foreign bodies, intussusceptions and ileus, largely superseding the use of BIPS and barium sulfate.

Effective ultrasonography requires an experienced practitioner and a good quality machine, but is more accessible than both CT and MRI.

However, radiography is often more cost effective and more widely available – especially in remote locations.

Wooden foreign bodies in particular may be easily missed, leading to poor surgical outcomes, repeated visits and increased cost.

Kate Parkinson graduated from the University of Bristol in 2006. Since graduating, she has travelled to more than 50 countries and worked as a veterinarian in Australia, New Zealand and the UK. She works in small animal practice in Invercargill, New Zealand, where she combines her interests in writing and general small animal practice to write occasional veterinary articles.