14 Apr 2022

Case of Chiari-like malformation requiring surgical management

Bart Ropelewski endeavours to grow the understanding of Chiari-like malformations, their clinical presentation and treatment options.

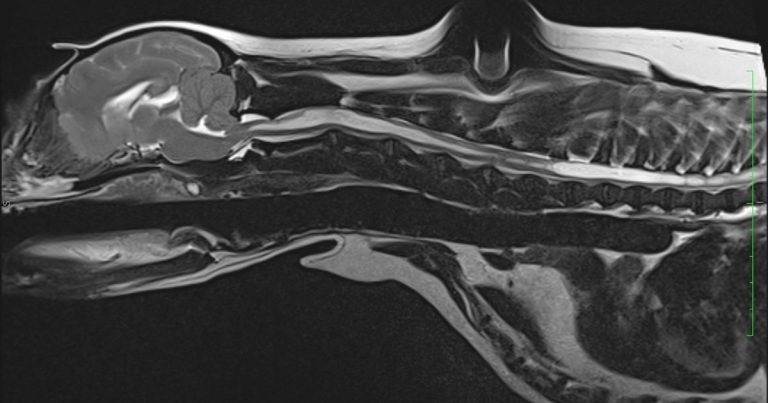

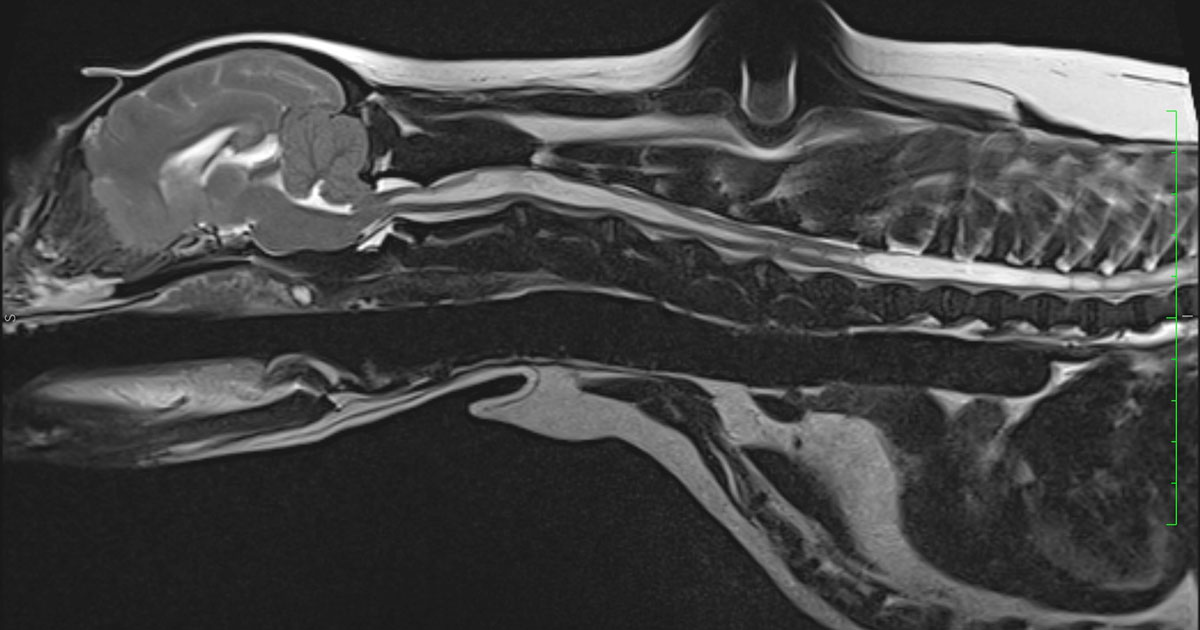

Figure 1. T2-weighted sagittal MRI scan of the six-year-old cavalier King Charles spaniel.

A six-year-old, female, neutered cavalier King Charles spaniel was referred to Rutland House referrals for investigation and treatment of suspected OA.

The owner reported that the dog was struggling with climbing stairs and had recently developed sleep disruption.

Within the past three months, the dog had started to experience a mild tremor affecting both hindlegs. It is also worth noting that, since being a pup, the dog had always scratched at its ears, and frequently rubbed its head against the owner’s legs and furniture.

Orthopaedic and neurological examination was overall unremarkable apart from moderate hindleg muscle atrophy, and aversion to touch of the head and neck area. Otoscopic assessment didn’t reveal any abnormalities in the external ear canal or tympanic membrane.

Following a discussion of possible treatment options and complications, the dog was admitted for further investigation.

Routine biochemistry and haematology were unremarkable. The patient was admitted for MRI scans under general anaesthetic.

T2-weighted (T2W; Figure 1) and T1-weighted (T1W) sagittal scans showed a significant cavitation located within the spinal cord, extending from C1 to L4.

The T2W transverse scan through the cord showed cavitation of approximately 75% of the cord diameter and had an oval shape, asymmetrically affecting the dorsal horn of the grey matter.

The occipital bone was displaced rostrally, causing a caudoventral portion of the cerebellar vermis to herniate through the foramen magnum, displacement of the caudoventral segment of the cerebellum, and decreased volume of the caudal cranial fossa.

Transverse T2W images through the brain revealed mild-to-moderate dilation of the third ventricle and obstruction of the CSF.

The findings were compatible with that of a profuse Chiari-like malformation (CM), and severe cervical and thoracolumbar syringomyelia.

Conservative treatment

Initially, a conservative treatment plan was prescribed to see how the dog responded.

This consisted of meloxicam 0.1mg/kg orally once a day, amantadine 4mg/kg orally once a day, gabapentin 30mg/kg orally daily, divided every 8 hours, omeprazole 1.5mg/kg orally every 24 hours and paracetamol 10mg/kg orally every 12 hours.

The patient was reassessed after four weeks. The owner reported no clinical improvement in the dog’s clinical symptoms and the dog had developed persistent gastrointestinal symptoms, including diarrhoea and vomiting. Use of NSAIDs was stopped and prednisolone was prescribed at a starting dose of 0.5mg/kg every 12 hours a day for a week, then reduced slowly to the lowest effective dose.

The patient was re-presented after three weeks. At this point, significant neurological deterioration was noted, including increased frequency of “phantom” scratching and generalised tremors. The dog had become very lethargic, unsettled, had started panting excessively and had significant sleep disruptions.

Several treatment options were discussed with the owner including adding amitriptyline (0.5mg/kg to 2mg/kg orally, once a day to twice a day) or topiramate (10mg/kg three times a day), the use of acupuncture or alternatively surgical management including stent surgery (syringo-pleural/peritoneal stenting), and/or foramen magnum decompression with cranioplasty.

The owner declined conservative treatment and elected decompression surgery.

Surgical management

The patient was premedicated with the use of medetomidine 0.05mg/kg, methadone 0.3mg/kg, paracetamol 10mg/kg, cefuroxime 15mg/kg and mannitol 0.5 g/kg IV over 10 to 15 minutes.

The dog was induced with propofol 4mg/kg IV and maintained with isoflurane in oxygen. Fentanyl bolus was given at the dose of 0.001mg/kg prior to fentanyl CRI.

Fentanyl CRI was administered intraoperatively at a dose of 0.005mg/kg and ended on recovery. Intravenous fluids were given throughout surgery.

The dog was placed in the sternal recumbency with the head placed in the ventroflexed position. An incision was made from the sagittal crest to the dorsal spinous process of C2, enabling complete exposure of the caudal occipital protuberance.

The atlanto-occipital membrane was removed using a scalpel blade and electrocautery. Foramen magnum decompression with cranioplasty was performed with the use of spinal burr and rongeurs.

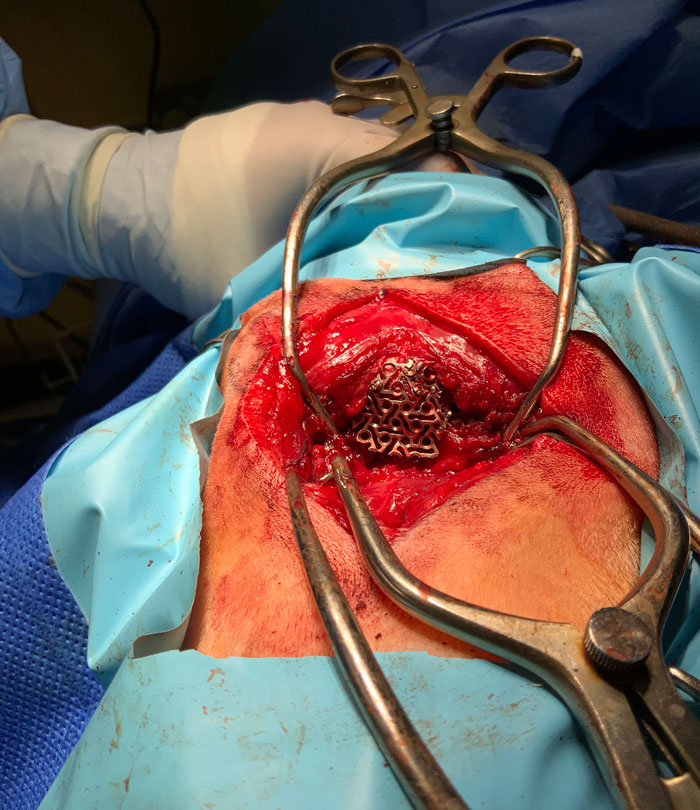

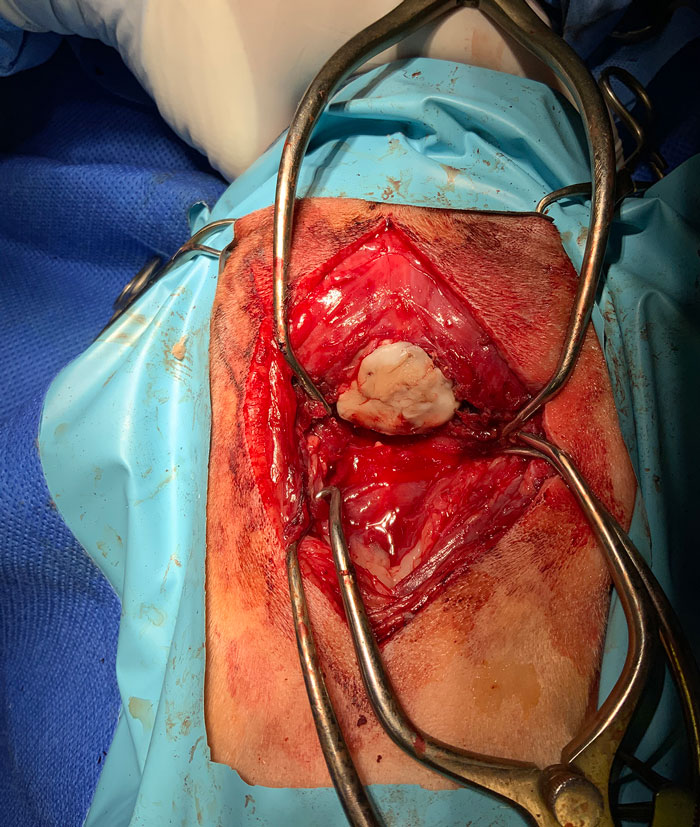

Five guide holes were created on the periphery of the bony defect using a 1.1mm drill bit. A custom-made titanium mesh was fixed to the skull using self-tapping titanium screws (Figure 2). Polymethylmethacrylate was placed over the skull mesh to avoid excessive scar tissue formation after surgery (Figure 3).

Routine closure was performed. The muscle layer was closed with 2/0 polydioxanone, subcutaneous layer with 2/0 monofilament, absorbable suture and skin with 2/0 nylon.

Every fours hours 0.2mg/kg IM methadone was administered. When the dog’s pain score was consistently low (three and below) over the 12-hour period, this was switched to buprenorphine (0.015mg/kg SC) every six hours.

Robenacoxib (2mg/kg to 4mg/kg orally daily) and gabapentin (10mg/kg mg orally every eight hours) were continued for three weeks postoperatively, then gradually withdrawn.

Oral cefalexin was administered (20mg/kg to 30mg/kg twice-daily for seven days, starting eight hours after the past IV cefuroxime).

The dog was hospitalised for five days post-surgically. Upon discharge, all previously noted neurological signs had resolved.

The dog was re-examined one month post-surgically and the owner reported a significant improvement.

No previously noted neurological deficits were present on clinical examination.

Chiari-like malformation discussion

CM is a congenital/developmental condition characterised by reduction of the caudal cranial fossa volume, resulting in insufficient space for the cerebellum and subsequent cerebellum herniation through the foramen magnum.

Herniated cerebellum affects normal CSF, leading directly to the formation of fluid-filled cavities (syrinx) within the spinal cord (syringomyelia; SM; Rusbridge et al, 2006a). CM is most commonly diagnosed in cavalier King Charles spaniels.

A hereditary nature of this malformation appears to be present (Lewis et al, 2010). It is also seen in griffon Bruxellois, Maltese, Pomeranian, Chihuahua, Yorkshire terrier and French bulldogs (Marino et al, 2012).

Symptoms

Clinical symptoms can vary from very mild to acute. A significant number of dogs will experience some level of neuropathic pain (Todor et al, 2000).

Neuropathic pain linked to CM and SM may be intermittent or persistent, and can be found mainly in the cervical region. Certain activities can increase the level of pain (getting up, excitement or exercising). Some patients are reluctant to be touched near the ear, neck or shoulder areas due to significant skin hypersensitivity. Dogs with syrinx may also develop “phantom scratching”, typically only on one side (Rusbridge et al, 2006b).

In dogs affected by CM, the presence of a large syrinx in the dorsal part of the spine predisposes them to inevitable destruction of the dorsal spinal horn.

Structural damage of the dorsal spinal horn has been directly linked to neuropathic pain (Rusbridge et al, 2006).

Patients may develop a number of neurological deficits, ranging from mild front and hind legs muscle atrophy and weakness, to marked pelvic limb ataxia (Rusbridge et al, 2000). Other symptoms may include scoliosis (Rusbridge et al, 2000) and progressive deafness and facial nerve paralysis (Munro and Cox, 1997).

Typically, CM and SM can manifest clinically at different life stages depending on the severity of neurological damage. The average age of presentation ranges from six months to three years of age (Rusbridge and Knowler, 2004). Diagnosis of CM and SM requires MRI scanning.

Treatment options

Asymptomatic cases of CM and syrinx do not require any medical or surgical management.

A similar treatment approach is used in human cases (Medow et al, 2006). Medical treatment may vary depending on the level of severity of the clinical symptoms.

Treatment needs to address two main issues: neuropathic pain and reduction in production of CSF. In clinical studies, drugs proven to fulfil these requirements include analgesics, (NSAIDs, gabapentine, paracetamol), selective and irreversible proton pump inhibitor (omeprazole) to decrease production of CSF, and corticosteroids (Rusbridge and Jeffrey, 2008).

Mild cases can be effectively treated with the use of NSAIDs (Rusbridge et al, 2000).

More severe cases may require additional drugs to control neuropathic pain (Panel 1).

- Gabapentin 10mg/kg to 20mg/kg every 8 hours (Radulovic et al, 1995).

- Pregabalin 4mg/kg every 12 hours (Salazar et al, 2009).

- Amitriptyline 3mg/kg to 4mg/kg every 12 hours (Kukes et al, 2009).

- Amantadine 3mg/kg to 5mg/kg every 12 to 24 hours (KuKanich, 2013)

In cases where neuropathic pain is not controlled with the use of NSAIDs, gabapentin and paracetamol, then adding oral prednisolone could be considered at anti-inflammatory doses of 0.5mg/kg orally every 12 to 24 hours for a week, then slowly decreasing to the lower effective dose (Barnes, 1998). Treatment in these cases is likely life-long as only symptomatic.

Surgical management is only indicated in cases failing to respond to conservative management. In these cases, foramen magnum decompression is performed. This involves removing part of the suboccipital bone from the region of compressed cerebellum and the cranial portion of the dorsal C1 laminae with or without the durotomy (Dewey et al, 2004; Vermeersch et al, 2004).

In one clinical study for dogs undergoing foramen magnum decompression, 81.25% of their clinical symptoms were resolved or significantly improved. However, 25% of patients had a relapse of clinical symptoms soon after surgery due to scar tissue formation at the surgical site (Dewey et al, 2005). One option to eliminate the risk of scar tissue formation is foramen magnum decompression combined with cranioplasty.

Placing a titanium mesh fixed with self-tapping screws over the decompressed cerebellum limits potential scarring.

An alternative treatment option in such cases is syringosubarachnoid shunting (Skerrit and Hughes, 1998).

- Some of the drugs in this article are used under the cascade.