7 Oct 2025

James Guthrie BVM&S, CertAVP(GSAS), PgCertVBM, CCRT, DipECVS, DipACVSMR, DipECVSMR, FRSB, FRSA, MRCVS and Chris Parker BVMSci, MRCVS discuss how not to mistake this condition for the more common cranial cruciate ligament rupture and treatment strategies.

Figure 1: Radiographs of (A1) normal feline stifle, (A2) caudal tibial displacement due to caudal cruciate ligament rupture, (B1) normal canine stifle, (B2) cranial tibial displacement due to cranial cruciate ligament rupture. The femoral condyles (orange curve) relationship to the tibial intercondylar eminence (blue arrow) can be compared between images A and B.

The caudal cruciate ligament acts as the primary stabiliser against caudal tibial subluxation relative to the femur (caudal drawer). It also functions together with the cranial cruciate to limit internal rotation and hyperextension of the stifle (Arnoczky et al, 1977; Tobias and Johnston, 2012).

Caudal cruciate ligament rupture is typically the consequence of trauma. It is uncommon for this ligament to be injured in isolation, making it lower on the differential list for causes of stifle lameness. Injury is usually associated with rupture of other ligaments, most frequently the medial collateral ligament and/or cranial cruciate ligament (Tobias and Johnston, 2012).

It is well documented that cranial cruciate ligament rupture is the result of non-traumatic pathology. Abnormal biomechanics, which can cause excessive loading on the ligament, is one of the multifactorial attributes that could increase the risk of rupture. Some clinicians have suggested that caudal cruciate ligament rupture may share similar pathogenesis whereby abnormal biomechanics contributes to an increased risk factor making rupture more likely (Kopp et al, 2020), although more often than not trauma occurs.

Abnormal biomechanics have been described in terms of narrowed intercondylar notches, but most notably of excessively low tibial plateau angles. A low TPA will contribute to an increase in risk of rupture due to excessive loading on the caudal cruciate. This is supported by the reported complication of TPLO surgery that because of tibial plateau rotation, cranial thrust is transformed into caudal thrust causing predisposition to fatigue failure and rupture (Zachos et al, 2002).

Diagnosing caudal cruciate ligament rupture in a primary care setting relies on detailed history taking, a thorough hands-on examination of the limb (often best performed under sedation or general anaesthesia in tense/painful patients) and radiography to assess changes consistent with caudal cruciate ligament rupture.

A consistent finding in caudal cruciate ligament rupture is a pelvic limb lameness that varies in severity from mild weight bearing to non-weight bearing. History often reveals a moderate to severe traumatic incident, which differs from the frequent non-traumatic or mild trauma that can lead to rupture of the cranial cruciate ligament. The clinician may observe variation in muscle atrophy of the pelvic limb depending on chronicity associated with rupture.

A medial buttress may also be present, which often is overlooked as only associated with cranial cruciate disease. A caudal drawer of the stifle joint often indicates caudal subluxation indicative of caudal cruciate ligament rupture.

However, due to difficulty in differentiation between cranial and caudal drawer motion, a diagnosis of caudal cruciate ligament rupture is often missed. Indeed, a retrospective study of 14 dogs revealed that in 9 cases a differential diagnosis of caudal cruciate rupture was not included and 7 were misdiagnosed as having the more common, cranial cruciate ligament rupture (Johnson and Olmstead, 1987).

Tibial sag is another useful finding indicative of caudal cruciate disease. In a healthy, stable stifle joint the tibial tuberosity will prominently project from the cranial stifle. In cases of cranial cruciate disease, a cranial tibial subluxation will cause the tibial tuberosity to become more prominent. Alternatively, in cases of caudal cruciate disease, a caudal tibial subluxation will cause a reduction in the prominence of the tibial tuberosity commonly observed as becoming flat or concave (Tobias and Johnston, 2012).

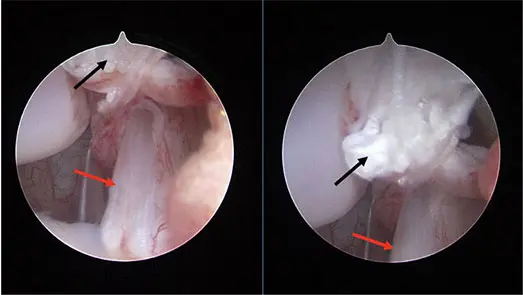

Abnormal radiographic findings may include avulsion fragments (more commonly of the femoral attachment over the tibial attachment), increased soft tissue opacity and caudal tibial subluxation (Figure 1). Stifles with a rupture of the caudal cruciate ligament typically have less osteophytosis associated with them compared to dogs who have cranial cruciate ligament rupture. This may be due to the lack of a prodromal period of degeneration within the joint, or perhaps less joint damage is induced from this direction of instability (Pournaras et al, 1983). A definitive diagnosis can be achieved from advanced imaging such as an MRI scan or observation via arthroscopy or arthrotomy (Figure 2).

In a case of caudal cruciate ligament rupture, a caudal tibial subluxation will often occur because of the pull of the hamstring muscles. When examined there is a tendency for the tibia to move cranially, which is mistaken for cranial drawer. However, this is instead the action of the tibia returning to a neutral position from a position of caudal tibial subluxation.

Therefore, accurate recognition of the neutral position of the tibial plateau relative to femoral condyles is paramount in avoiding this mistake (Might et al, 2013; Tobias and Johnston, 2012).

The ability to recognise the neutral position of the tibia and direction of drawer is not only important for accurate diagnosis, but to derive an appropriate treatment plan to optimise case outcome.

Should cranial drawer motion be detected and further radiographic assessment conclude rupture of the cranial cruciate ligament, an appropriate surgical management strategy will often be proposed as this can lead to improved outcomes.

Conversely, should caudal drawer motion be detected and radiographic assessment concludes caudal cruciate ligament rupture, a more conservative management-based strategy is often advised, as this can still achieve good functional outcomes (Harari et al, 1987).

However, should a misdiagnosis of caudal cruciate disease be made when in fact cranial cruciate disease is present, an inappropriately implemented conservative management will likely result in continued lameness, as well as increasing risks of meniscal injuries (Pournaras et al, 1983) and more rapid progression of osteoarthritis (Harari et al, 1987).

Surgical management for caudal cruciate ligament rupture is advocated in patients that do not respond to conservative management and has also been anecdotally suggested by some clinicians for dogs with higher exercise demands (such as working or sporting dogs).

For multi-ligamentous stifle injuries, surgery is often recommended. Procedures to directly address the ruptured caudal cruciate ligament may or may not be incorporated into the surgical repair (Coppola, 2022).

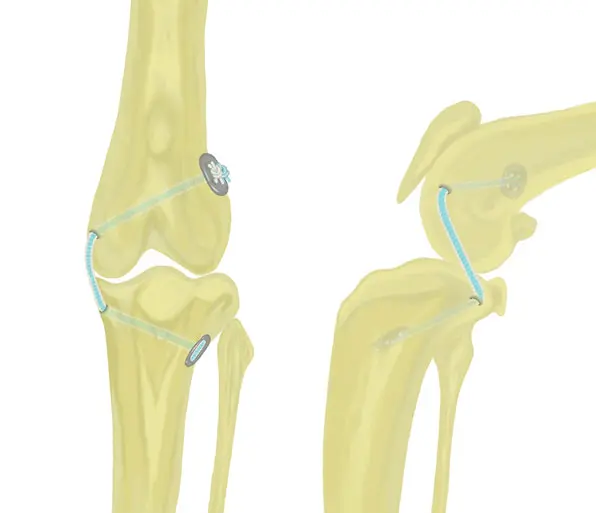

Surgical techniques typically involve synthetic intra or extra-articular ligament augmentation (Johnson and Olmstead, 1987; Fauqueux et al, 2023). In patients with an intact cranial cruciate ligament, surgeons should be careful not to injure this ligament if considering an intra-articular replacement of the caudal cruciate ligament. In these scenarios the authors prefer to use an extra-articular technique (Figure 3).

Correctly identifying rupture of the caudal cruciate ligament has occurred rather than rupture of the cranial ligament is important as standard treatment protocols differ (surgery versus conservative). Surgeons should be careful not to make a misdiagnosis and perform a surgery for appropriate for rupture of the cranial cruciate ligament, when in fact the caudal ligament has torn. Formal rehabilitation could aid recovery by improving muscle strength and joint proprioception to improve stifle stability.