25 Mar 2019

Cervical spondylomyelopathy in dogs – diagnosis and treatment

Steven de Decker discusses two forms of this disorder, including presentation, and therapeutic approaches and their challenges.

Cervical spondylomyelopathy (CSM) is a complex, multifactorial neurological syndrome characterised by predominantly caudal, cervical vertebral canal stenosis. Over the years, two more separate forms have been recognised: disc-associated CSM (DA-CSM) and osseous-associated CSM (OA-CSM).

Spinal cord compression is predominantly caused by protrusion of one or more intervertebral discs in DA-CSM, and by articular process hypertrophy in OA-CSM. DA-CSM most commonly affects older large-breed dogs, such as Dobermanns; while OA-CSM most often affects young giant-breed dogs, such as great Danes. Although survey radiographs can demonstrate specific abnormalities in dogs with DA-CSM and OA-CSM, a diagnosis can only be confirmed by myelography, CT-myelography or MRI.

Treatment of CSM is challenging and controversial. Medical management of DA-CSM and OA-CSM is associated with a guarded prognosis. More than 30 surgical techniques have been reported for DA-CSM, and an important post-surgery complication is recurrence of clinical signs attributable to development of disease at an adjacent disc space – referred to as adjacent segment disease. Surgical treatment for OA-CSM consists of a dorsal cervical laminectomy. Although this procedure is often associated with early postoperative neurological deterioration and intense rehabilitation, long-term outcome is often good.

Cervical spondylomyelopathy (CSM) – or wobbler syndrome – is a complex, incompletely understood, multifactorial and controversial neurological syndrome1.

The uncertainty surrounding this syndrome is illustrated by the fact more than 10 synonyms are used to refer to this condition – including CSM, wobbler syndrome, cervical stenotic myelopathy, cervical vertebral instability syndrome, and cervical vertebral malformation-malarticulation syndrome2.

CSM can be considered a collective of disorders in which cervical vertebral canal stenosis is caused by a combination of bone and soft tissue structures1,2.

Based on signalment and diagnostic findings, separate clinical syndromes have been recognised over the years. The two best characterised syndromes are disc-associated CSM (DA-CSM) and osseous-associated CSM (OA-CSM).

Both forms are associated with differences in signalment, pathological abnormalities and imaging findings, surgical techniques and postoperative complications, and, possibly, outcomes1,2. Although controversial, it is, therefore, possible both DA-CSM and OA-CSM should be considered entirely different neurological disorders.

Pathophysiology and aetiology

Although many factors have been proposed, the exact pathophysiology and aetiology of CSM are unknown1,2.

Because of the breed predispositions for Dobermanns and great Danes, hereditary – and possibly genetic – aetiologies have historically been considered. Although previous studies – consisting of pedigree analysis – have not been able to establish a hereditary component7, studies using modern genetic analysis have not yet been performed. Other studies have been unable to demonstrate an association between CSM and body conformation or nutritional factors8,9.

CSM is a multifactorial disorder in which a combination of static and dynamic factors contribute to the development of caudal cervical spinal cord compression1,2. Dynamic factors represent changes in the dimensions of the vertebral canal when the animal makes physiological movements of the neck. The vertebral canal typically becomes narrower when the neck is dorsally extended and wider when the neck is ventrally flexed10. This can result in dynamic spinal cord compression, which should not be confused with the presence of vertebral instability2.

Although CSM has historically been associated with vertebral instability, to date no study has evaluated or demonstrated vertebral instability in dogs with CSM1,2. Therefore, no reason exists to consider vertebral instability as an important factor in the development of CSM.

Clinical signs

Clinical signs in dogs with DA-CSM and OA-CSM are caused by chronic caudal cervical spinal cord compression – and can vary from cervical hyperaesthesia without a gait abnormality, to non-ambulatory tetraparesis.

A typical clinical presentation is, however, a chronic and progressive wide-based ataxia and paresis of the pelvic limbs, in combination with a short and stilted gait in the thoracic limbs. This gait is often referred to as a “two-engine” or “disconnected” gait and can be considered suggestive of a caudal cervical spinal problem2.

It can, occasionally, be challenging to localise the clinical signs to a cervical problem; affected dogs can demonstrate obvious gait abnormalities in the pelvic limbs, while only minimal or no observable gait abnormalities are observed in the thoracic limbs. These lack of clinical signs in the thoracic limbs are caused by the specific anatomical organisation of the nerve tracts in the cervical spinal cord, and can make it challenging to differentiate between dogs with a chronic neck or thoracolumbar spinal problem1.

Although obvious cervical hyperaesthesia is not always present, affected dogs often demonstrate resistance to specific neck manipulations1,2. Dogs with DA-CSM often resist dorsal cervical extension, while dogs with OA-CSM often resist dorsal extension and lateral bending of the neck.

DA-CSM diagnostic approach, treatment and outcome

DA-CSM most often affects large-breed dogs older than seven years. Although every breed can be affected, the Dobermann is over-represented in many studies3,4,11.

In DA-CSM, progressive caudal cervical spinal cord compression is caused by one or more intervertebral disc protrusions12. The intervertebral disc spaces between C6-C7 and C5-C6 are most often affected, and multiple sites of spinal cord compression are seen in between 20% and 50% of cases4,12,13. This ventral, “disc-associated” compression is sometimes seen in combination with dorsal spinal compression caused by ligamentum flavum hypertrophy.

Other abnormalities can include a funnel-shaped vertebral canal with narrowing of the cranial orifice, an abnormal craniodorsal tilting of the vertebral body, and vertebral body abnormalities. Vertebral body abnormalities are often mild and, most typically, consist of a flattening of the ventrocranial border of the vertebral body of C712.

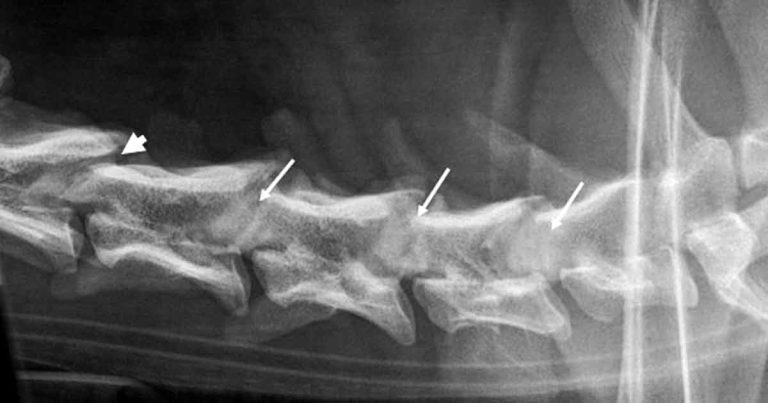

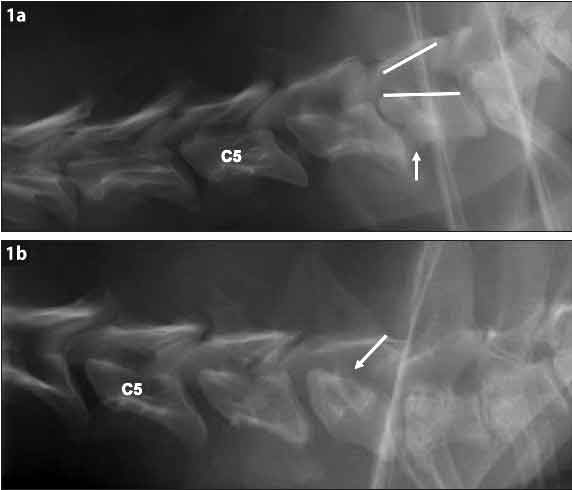

Although survey radiographs can be suggestive for DA-CSM, diagnosis can only be confirmed with myelography, CT-myelography (CT-m) or MRI1,14. Abnormalities on survey radiographs can include a narrowed or collapsed intervertebral disc space, sclerotic vertebral endplates, craniodorsal tilting or an abnormally shaped vertebral body, spondylosis deformans, and the vertebral canal appearing stenotic with the cranial orifice narrower than the caudal orifice (Figure 1)12,15,16. The latter is also referred to as a “funnel-shaped” vertebral canal16.

Although DA-CSM can be diagnosed by myelography, this diagnostic technique can be considered invasive and is associated with several complications. The most commonly observed myelographic complications in dogs with DA-CSM are seizures (in up to 27% of cases) and transient neurological deterioration (in up to 14% of cases) after the myelographic procedure13,14. The same complications can be seen after CT-m.

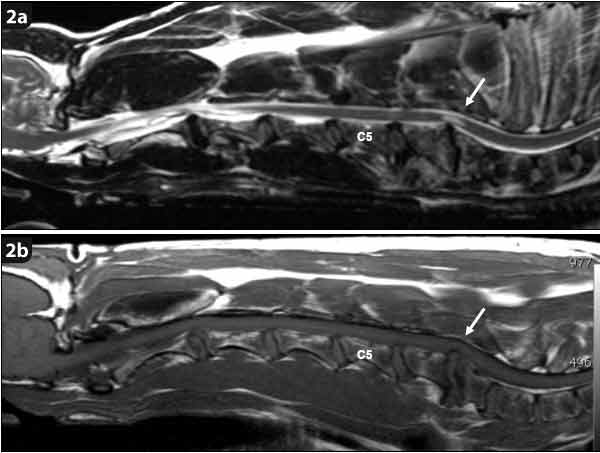

Because of its safe and non-invasive character, MRI should be considered the imaging modality of choice (Figure 2)1.

The value of performing dynamic studies – consisting of traction, flexion and extension views – has been reported to evaluate the dynamic component of spinal cord compression in dogs with CSM. Applying traction and flexion can alleviate or improve spinal cord compression, while dorsal extension can worsen spinal cord compression in dogs with DA-CSM2.

It has been suggested the results of dynamic studies, especially traction studies, can guide surgical decision-making12. Concerns have been raised that prolonged dorsal extension of the cervical vertebral column can result in neurological deterioration1. Although dynamic studies have traditionally been performed during myelography, studies have also described the use of dynamic MRI17.

Because the aim of dynamic studies is to evaluate how the degree of spinal cord compression changes in response to movement of the neck, no value exists in performing dynamic studies during survey radiographic studies. It should, again, be emphasised the concept of dynamic spinal cord compression is not the same as vertebral instability. Vertebral instability has not been objectively demonstrated in dogs with CSM and performing dynamic studies does not represent evaluation of vertebral instability.

Treatment of DA-CSM is challenging and controversial18. Although little is known about the role of medical management, studies have suggested a guarded prognosis, with clinical improvement achieved in between 38% and 54% of cases3,4,11. If medical treatment fails, dogs typically become non-ambulatory in the first 6 to 12 months after a diagnosis of DA-CSM4,11.

More than 30 surgical techniques have been reported for DA-CSM and new ones are continuously being reported19. This unprecedented high number of techniques for a single condition can be considered a reflection of the challenges associated with this neurological syndrome. It is safe to say the ideal surgical technique has not yet been developed. This overwhelming number of surgical techniques can be divided into three categories:

- direct decompressive, or ventral slot surgery

- distraction-stabilisation techniques18,20

- cervical arthroplasty or artificial intervertebral disc replacement21,22

An important complication after initial successful surgery is recurrence of clinical signs caused by the development of disease at an adjacent intervertebral disc space2,12. This complication is referred to as adjacent segment disease or domino lesion, and occurs in approximately 20% of initially successfully treated cases and within the first two to three years after initial surgery2,12,18,20.

Although, the underlying cause of adjacent segment disease is unknown, two (not mutually exclusive) theories have been proposed18. The first theory has suggested spinal surgery at one disc space can cause altered biomechanics and increased stress at an adjacent intervertebral disc space. The second theory suggests adjacent segment disease represents a natural progression of a disease that intrinsically affects multiple intervertebral disc spaces18. A similar prevalence of adjacent segment disease is seen after direct decompressive (ventral slot) and distraction-stabilisation techniques (pins and poly[methyl methacrylate])20.

Although cervical arthroplasty has the theoretical advantage of preserving motion at the vertebral segment, further studies are necessary to evaluate whether this surgical technique will result in a decreased prevalence of adjacent segment disease21,22.

OA-CSM diagnostic approach, treatment and outcome

OA-CSM most often affects young giant-breed dogs (aged between 12 and 48 months) – such as the great Dane, bullmastiff and dogue de Bordeaux2,6.

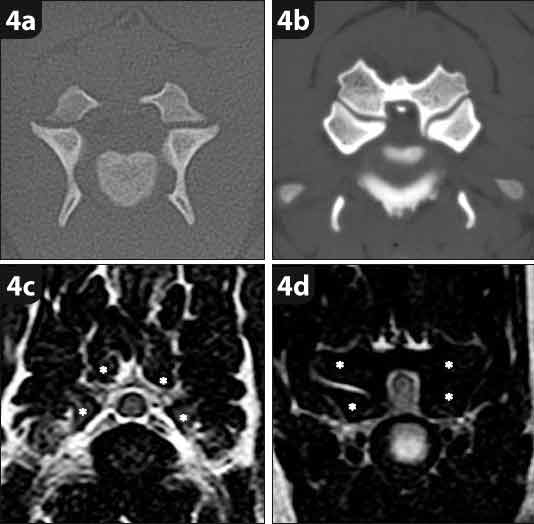

In OA-CSM, dorsal, dorsolateral or lateral spinal cord compression is predominantly caused by degeneration and hypertrophy of the articular processes5. This is often seen in combination with ligamentum flavum hypertrophy. Additional abnormalities can include hypertrophy or malformation of the dorsal lamina and dorsal spinous processes2,6,23.

Although the caudal cervical vertebral column is most often affected, the cranial intervertebral can also be involved, with about 85% of affected dogs demonstrating multiple sites of spinal cord compression23.

Survey radiographs can reveal specific abnormalities in dogs with OA-CSM, which include obliteration of the intervertebral foramina by “rounded” radiopaque structures originating from the articular processes. The normal facet joint can often not be visualised on radiographs of dogs with OA-CSM (Figure 3).

Similar to dogs with DA-CSM, a diagnosis of OA-CSM cannot be confirmed on survey radiographs – MRI should be considered the imaging modality of choice (Figure 4).

Little is known about the results of medical management in dogs with OA-CSM. It has been suggested affected dogs can have an acceptable response to medical management characterised by a continued, but slow, progression of clinical signs6. In the author’s institution, 38% of dogs have a good long-term outcome after medical treatment for OA-CSM (De Decker, unpublished observation).

Although this early postoperative neurological deterioration can be associated with intense, expensive and prolonged hospitalisation times, this deterioration is, fortunately, typically transient. Most dogs will experience a good long-term recovery6,24. In the author’s institution, 94% of dogs have a good long-term outcome after surgical treatment for OA-CSM (De Decker, unpublished observation).