14 Oct 2025

Trish Ward MVB, DipECVIM-Ca, PGCAP, MRCVS and Sneha Joseph Pugalendhi BVM&S, MRCVS discuss the possible treatment and management actions for this condition.

Image: 5second / Adobe Stock

Chronic kidney disease (CKD) is a common concern among senior cats. The prevalence of CKD is estimated to be approximately 2% to 4% in the overall population and increases to 30% in cats aged older than 10 years1.

The diagnosis of CKD often occurs in its later stages based on a combination of clinical signs, azotaemia, and an inappropriate urine specific gravity (USG) of less than 1.0351. The biomarker, symmetric dimethylarginine (SDMA), can aid in the early diagnosis2. Together with creatinine, SDMA enhances the assessment of renal excretory function, with both markers forming the basis of CKD staging, as defined by the International Renal Interest Society (IRIS). IRIS categorises CKD into stages one through four, providing evidence-based guidelines for diagnosis and treatment3.

Additionally, proteinuria and blood pressure are also key variables to monitor. Both proteinuria and hypertension are independent risk factors that increase mortality in cats with CKD3,4. Sub-staging based on these variables further informs treatment and management strategies, tailoring care to the individual patient’s needs3.

While renal diets are the cornerstone of CKD management, several adjunctive treatments can provide additional support5. This article aims to cover and summarise additional therapies that can improve the quality of life of our feline patients.

Serum phosphate tends to be retained in CKD, resulting in hyperphosphataemia. Increased phosphorus concentrations are associated with shorter renal survival times and contribute to renal secondary hyperparathyroidism, tissue mineralisation and progression of CKD.

Previously, dietary phosphate restriction was recommended immediately after a CKD diagnosis to prevent hyperphosphataemia6. Newer guidelines advise against restricting dietary phosphate in normophosphataemic cats due to the risk of hypercalcaemia3.

Fibroblast growth factor-23 (FGF-23), a newer diagnostic tool, is now recommended to assess whether a patient would benefit from phosphate restriction. FGF-23 levels of more than 400pg/ml in the absence of hypercalcaemia, anaemia, or marked inflammation indicate the need for dietary phosphate restriction. The latest IRIS guidelines suggest a goal phosphate concentration of less than 1.5mmol/L (but not less than 0.9mmol/L) for feline CKD patients. In stage 4 CKD, a target of 1.9mmol/L may be more realistic3.

In cases where dietary restriction alone does not achieve target phosphate levels (or if the cat is not accepting the renal diet), an intestinal phosphate binder may be introduced3,6. Treatment with phosphate binders should be to effect, with serum phosphate and calcium being rechecked every four to six weeks until stable and then every 12 weeks thereafter. Once serum phosphate is within the reference range, FGF-23 can help determine if further phosphate restriction is necessary. FGF-23 levels of more than 700pg/ml may indicate a need for higher phosphate binder doses3. As CKD progresses, phosphate retention will inevitably increase, necessitating dose adjustments for phosphate binders3,6.

Commonly used phosphate binders in the UK are chitosan and calcium carbonate based3,6,7. Binders work best when given within two hours of feeding to increase bioavailability. To avoid interference, administer other oral medications at least one hour before or three hours after feeding6,7.

Hypokalaemia is a common complication of CKD, affecting approximately 20% to 30% of patients8. Although the exact mechanism remains incompletely understood, increased potassium loss through kaliuresis, vomiting, transcellular shifts, and reduced dietary intake likely contribute9.

Early intervention is crucial, as hypokalaemia worsens symptoms such as muscle weakness, polyuria, polydipsia, anorexia and constipation8,9. Routine monitoring of serum potassium is recommended in cats with CKD, with supplementation advised if levels fall less than 3.5mmol/L8. Consider supplementation where serum potassium is in the low-normal range (3.5mmol/L to 3.9mmol/L), though the clinical benefits at this level remain uncertain9.

Oral potassium supplementation is effective for CKD-related hypokalaemia8, and several preparations are used in the UK. Depending on the clinical response and serum potassium levels, dosages are adjusted to the lowest effective dose7.

Hypertension is strongly associated with CKD and is a cause and consequence of the disease4,10. The prevalence of hypertension in cats with CKD varies, with estimates from 20% to 65%9,10. A systolic blood pressure (SBP) consistently more than 160mmHg to 180mmHg defines hypertension10.

Blood pressure should be measured at the time of CKD diagnosis and reassessed every three to six months, following IRIS hypertension guidelines3,10. Uncontrolled hypertension can cause target organ damage (TOD) in the eyes, heart, cerebrovascular tissue and kidneys9,10. Hypertension also exacerbates proteinuria, an independent risk factor for CKD progression and mortality9,10.

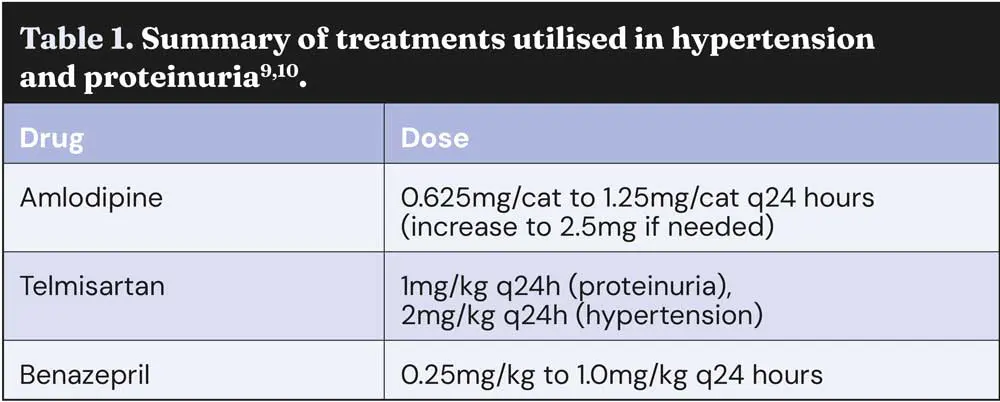

Amlodipine is the first-line treatment for hypertension in cats10. As a calcium channel blocker, it reduces SBP by 30mmHg to 70mmHg through peripheral arterial dilation10. Telmisartan (an angiotensin receptor blocker) and benazepril (an angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor) are second-line agents, reducing the SBP by 10mmHg to 20mmHg10. These drugs may be added to amlodipine if monotherapy fails to achieve blood pressure control and are also effective in managing proteinuria11. Treatment should begin with amlodipine, at 0.625mg/cat every 24 hours, increasing to 1.25mg/cat if the SBP exceeds 200mmHg7,10. A transdermal formulation is also available, but further studies are required to compare it to the oral formulations9,10.

Cats with evidence of TOD and/or severe hypertension (SBP of more than 200mmHg) require close monitoring during the first 24 to 72 hours of treatment. For stable patients, SBP should be monitored every seven to 10 days until a target SBP of less than 160mmHg is achieved within one to two weeks. In the long term, a SBP of 150mmHg is recommended9,10.

Caution is necessary to avoid hypotension, with SBP not falling less than 110mmHg10. Once blood pressure is under control, monitoring should occur every three months, alongside TOD examination, blood work and urinalysis10.

Proteinuria is associated with a poorer prognosis in CKD and contributes to disease progression4,9,10. It may result from systemic hypertension, causing glomerular hypertension and increased urinary protein loss. Therefore, assessing proteinuria via urine protein to creatinine ratio (UPCR) is crucial in CKD management.

IRIS CKD guidelines, categorise proteinuria as follows3:

Inhibition of the renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system (RAAS) significantly reduces the severity of proteinuria9. RAAS inhibition should be considered in cats with stable CKD when the UPCR remains persistently more than 0.4. Benazepril and telmisartan are the main RAAS inhibition drugs used for therapy3,9.

While both are effective in reducing proteinuria, treatment for concurrent hypertension can also help mitigate proteinuria by addressing glomerular hypertension9.

For cats with hypertension and proteinuria, it is advisable to stabilise blood pressure before evaluating the need for additional proteinuria therapy9,10. Adverse effects of RAAS inhibitors are uncommon, but may include worsening azotaemia, hypotension or hyperkalaemia – particularly in advanced CKD. These patients require careful monitoring of serum potassium, blood pressure and kidney function9.

The main drugs used to treat hypertension and proteinuria are summarised in Table 1.

Anaemia is present in 30% to 35% of cats with CKD11. It primarily arises from reduced erythropoietin (EPO), a renal hormone that regulates the bone marrow’s production of red blood cells (RBC)8. Additional factors such as blood loss, a shortened RBC survival and reduced iron availability often exacerbate anaemia9. Treatment with erythrocyte-stimulating agents (ESA), such as recombinant human (epoetin alfa) or darbepoetin, is recommended when haematocrit falls to less than 20%, and/or clinical signs attributable to the anaemia are present9,11.

Stimulating erythropoiesis is associated with a high iron demand, and with a functional iron deficiency associated with CKD, iron supplementation is necessary to support treatment9. Success rates of erythrocyte-stimulating agents vary due to the development of antibodies secondary to treatment, which leads to pure red cell aplasia and non-responsiveness to therapy8,11.

A promising development is the emergence of hypoxia-inducible factor-prolyl hydroxylase inhibitors, a newer class of drugs currently under trial in the US. These drugs stimulate endogenous EPO production and may pose a lower risk of side effects such as hypertension, iron deficiency and polycythaemia, compared to traditional recombinant ESA drugs11,12. Further studies are required to establish their safety and efficacy in feline patients.

Cats with CKD can often experience inappetence, nausea, and vomiting due to the build up of uraemic toxins affecting the central chemoreceptor trigger zone9. These symptoms significantly impact the quality of life and should be managed proactively.

Anti-emetics targeting the central zones are the most effective in controlling nausea and vomiting9. Common examples include maropitant and ondansetron9. Mirtazapine is another useful adjunctive, as it reduces vomiting and stimulates appetite and weight13. It can also assist in transitioning to a renal diet by encouraging the patient with a better adaptation to the change.

Although H2 blockers and proton pump inhibitors (for example, famotidine and omeprazole) are sometimes used in CKD patients, evidence supporting their efficacy is limited, unless gastrointestinal ulceration is suspected.

However, hyperacidity-related ulceration is uncommon observed in feline CKD9,14. If acid suppression is necessary, omeprazole is recommended over famotidine9,15.

If nausea and inappetence persist despite treatments, hospitalisation with intravenous fluids and enteral feeding tubes may help. However, care monitoring of quality of life is essential.

Maintaining hydration is essential in CKD cats, as dehydration can exacerbate azotaemia and worsen clinical signs. The first approach is to ensure increased voluntary water intake is encouraged, by offering wet food, using water fountains or providing multiple water sources around the home8.

If voluntary intake is insufficient, water can also be administered through feeding tubes, providing both hydration and, if necessary, concurrent nutritional support9. If the owners are willing, subcutaneous fluid therapy can be another option for managing hydration9,16.

A survey of owners found that most (85% to 89%) considered subcutaneous fluids a low-stress experience for them and their cats. Success depends on warming fluids, using appropriate needle size and keeping sessions brief.

Hands-on veterinary training is key, and suitability should be assessed per cat, balancing benefits with quality of life – especially in early-stage CKD, where necessity remains debated16.

Beraprost is a newer drug aimed at inhibiting the progression of CKD and is currently undergoing clinical trials in the European market17. It is a prostacyclin analogue with vasoprotective effects on injured endothelial cells of the kidney18.

Studies in Japan, where the drug is licensed, have shown beraprost to be an effective and safe treatment for cats with CKD17,18.

Beraprost inhibited the decline in renal function in cats with stage 2 CKD and was associated with better overall survival times17,18. If the ongoing clinical trials confirm its efficacy and safety, beraprost could provide an alternative to the conventional RAAS-inhibitory drugs currently used16.

Managing feline CKD requires a multifaceted approach that extends beyond dietary interventions.

Early recognition of clinical symptoms and timely diagnosis are critical for slowing disease progression and improving outcomes.

The survival and well-being of feline CKD patients can be significantly enhanced using a combination of therapeutic interventions alongside dietary modifications.

Equally important is owner education. By helping owners understand CKD’s progressive nature and the rationale behind each therapeutic approach, treatment compliance can be improved and a more engaged approach to care can be encouraged.

Although CKD is progressive, proper intervention can improve affected cats’ survival and quality of life.