20 Feb 2024

Companion animal analgesia – overview of latest thinking

Karen Walsh outlines the pharmacological options that can be used for different conditions in these pets.

Image © sonsedskaya / Adobe Stock

Over the past 20 years, recognition and assessment of pain have become more widespread in veterinary medicine. This has been aided by the development of pain-scoring systems for acute and chronic pain.

Work has continued to be carried out to further develop systems that are simple and quick to use. In addition, investigation into patient caregiver’s use of these systems has been gaining traction.

Almost 50% of small animal practices in the US that were surveyed employed pain scales as part of their assessment (Costa et al, 2023). Pain, including the recognition, quantification and treatment of it, is one of the most common conditions small animal practitioners must deal with in general practice.

In surveys carried out at emergency clinics, one-third of the appointments seen by general practitioners included pain as one of the presenting complaints (Rousseau-Blass et al, 2020).

The role of the pet owner cannot be underestimated in the recognition and management of chronic pain. One study investigated the reliability of the feline grimace scale for acute pain when employed by cat caregivers of varying demographics and background, which demonstrated good correlation between caregivers and veterinarians (Monteiro et al, 2023).

Owners’ perception and descriptions, coupled with videos of the patient, are an important tool in assessing pain away from the veterinary clinic.

Several tools exist that have been developed for use in dogs and cats for both acute and chronic pain. The American Animal Hospital Association guidelines published in 2022 provides a good overview of the available tools, and if they have been validated (Gruen et al, 2022).

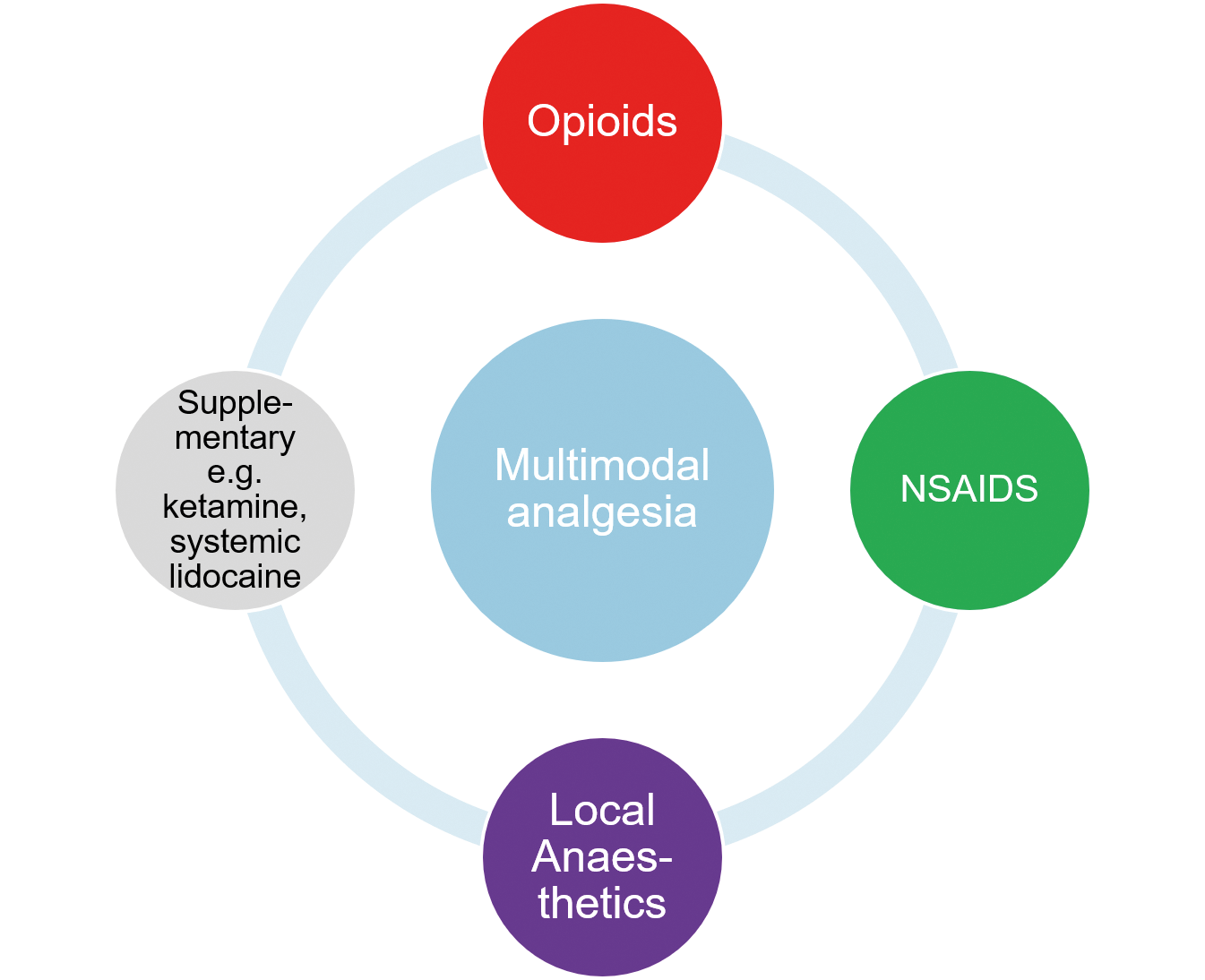

Multimodal analgesia

Multimodal analgesia involves using analgesics from different drug groups with the aim to reduce the total amount of each drug and improve the analgesic outcome for the patient.

Reducing the dose of any drug will hopefully lower the risk of side effects associated with high doses of certain drugs. Using this type of analgesic protocol will also reduce the reliance on one group; for example, opioids to provide analgesia.

The move away from reliance on opioid use has been initiated in human pain therapy because of the opioid crisis in many countries.

This has meant that the availability of opioids has been reduced or intermittent in some localities, prompting vets to utilise non-opioid methods of analgesia (Murrell, 2014; Figure 1).

NGF is involved in modulation of nociceptive input at the level of the nociceptor and at the dorsal root ganglion. Its role in the modulatory process may be a factor in the development of chronic pain.

Two licensed products for companion animals exist: frunevetmab for cats and bedinvetmab for dogs. These both contain NGF mAbs. The mAbs are species-specific and administered via injection subcutaneously.

The literature regarding the use of these biologic agents is mainly limited to the pre-licensing studies. At the time of writing, two papers are associated with clinical use of this agent which followed a similar construction (Michels et al, 2023; Corral et al, 2021). They are relatively short term, looking at the first 12 weeks of treatment compared to administration of a placebo. In both studies, both treatments led to improvements in quality of life (less in the European study by Corral et al, 2021). The effect of bedinvetmab plateaued at day 42.

Frunevetmab also showed a plateau effect at approximately day 56 (Gruen et al, 2021) in the pre-licensing literature. Frunevetmab had a greater beneficial effect than the placebo.

At the time of writing, minimal peer reviewed publications exist regarding “real-world use”. One case series has been published detailing adverse skin reactions in five cats (Storrer et al, 2023). Some anecdotal reporting exists of improved quality of life and movement in dogs and cats on owner forums. Interestingly, one online survey conducted found that greater than 80% of owners felt they had seen improvement when bedinvetmab had been administered to their dogs (Marlin, 2023).

Importantly, only one publication has investigated the use of an NSAID (carprofen) at the same time as bedinvetmab (Krautman et al, 2021). Carprofen was used alongside bedinvetmab for two weeks and did not appear to increase the number of adverse events. However, the current data sheet for both licensed mAbs warns that the concurrent use of NSAIDs and mAbs does not have safety data.

Grapiprant

Grapiprant is a member of the prostaglandin receptor antagonist group of drugs. It specifically targets the EP4 prostaglandin receptor, which is thought to be a key part in the prostaglandin E2 mediated sensitisation of sensory nerves and PGE2 inflammation.

The aim of using such a specific drug is to minimise the potential side effects that are seen with NSAIDs, but still achieve pain relief and anti-inflammatory action. It is a relatively new drug on the market (2018) in Europe, and much of the evidence is reliant on experimental data. One experimental study compared grapiprant to firocoxib in an acute arthritis model and found that it did not perform as well as firocoxib in that situation (Alcalá et al, 2019). This study was funded by the maker of Previcox (firocoxib; Boehringer Ingelheim Animal Health).

One abstract presented at a recent conference compared grapiprant with carprofen for dogs undergoing elective ovariohysterectomy and found that it was an alternative to traditional NSAIDs in that situation (Ross et al, 2022).

Non-pharmacological pain management options for OA

Mesenchymal stem cells

Mesenchymal stem cells is the most common term used to describe the progenitor cells that can subsequently differentiate into several different cell types (Pittenger et al, 2019). The most used source in clinical use in dogs is adipose tissue.

The beneficial effects are thought to be due to bioactive molecules (Pye et al, 2022). It has become increasing popular in veterinary and human medicine.

Olsson et al (2021) undertook a meta-analysis of 1,483 articles published in the veterinary literature to try to establish the efficacy of this type of treatment. Although only six of the articles met the criteria for inclusion, they did conclude that autologous or allogeneic adipose tissue stem cells may have some beneficial effect on pain levels and function in canine hip OA. They also reported that the procedure appeared to be well tolerated with minimal or no adverse events.

However, they did recommend that better multi-centre, large cohort studies need to be conducted to truly establish whether this treatment is beneficial.

Platelet-rich plasma

Autologous plasma component of blood that has a high concentration of platelets is known as platelet-rich plasma (PRP). As well as platelets, the plasma contains growth factors and cytokines which may act alone or in combination to encourage stem cell scaffolding, promoting new bone growth, blood vessel formation and migration of cells to the affected area.

The use of this technique has been used in humans, as well as veterinary species (Kaneps, 2023). It is difficult to compare between publications, as differences are often reported in methods of preparation and evaluation of effect.

Therapeutic laser

Low-level laser therapy has become popular in recent years as an aid to pain management. The proposed mechanism of action is by direct and indirect effects on nociceptors, modulation of inflammation and suppression of central sensitisation.

As with many treatment modalities for chronic pain in human and veterinary medicine, the mechanism and effectiveness of treatment is not known. A recent study using low-level laser therapy in client-owned dogs with OA did seem to show some positive effect – improved quality of life – as reported by owners (Barale et al, 2020).

Treatments for surgical analgesia

Maropitant

Maropitant is licensed to prevent and treat nausea due to chemotherapy, associated with morphine administration and other causes. It is a neurokinin-1 (NK-1) inhibitor, the result being blocking the action of substance P on the central nervous system.

Substance P is involved in a large number of processes, including pain processing via NK-1 receptors in the peripheral nervous system and the spinal cord. This has encouraged researchers to investigate the use of these drugs in treatment of particularly visceral pain.

‘Not all therapies will be pharmalogical, and it is important to consider non-pharmalogical therapies in acute and chronic pain.’

Papers on both dogs and cats exist that have investigated its use for ovariectomy and ovariohysterectomy surgeries. Maropitant as a CRI of 100mcg/kg/hr has been used in cats and found to be non-inferior to lidocaine or ketamine CRIs (Corrêa et al, 2021), and resulted in less-frequent rescue analgesia (Corrêa et al, 2019).

In dogs, two studies used maropitant 1mg/kg in the pre-anaesthetic medication and found reduced inhalant requirements, lower pain scores and faster return to eating than when compared to morphine (Marquez et al, 2015), and non-inferiority to methadone 0.3mg/kg in postoperative pain scoring (Cubeddu et al, 2023).

One report exists of using maropitant (bolus plus CRI 100mcg/kg/hr) as part of a multimodal analgesia for canine mastectomy, which reported lower pain scores and less rescue analgesia in the maropitant group (Soares et al, 2021).

Using maropitant as an analgesic is off-license. It is worth considering including it in an anaesthetic protocol if visceral pain is anticipated. As a putative visceral analgesic action occurs, it is also worth considering the use of maropitant when evidence of visceral pain in medical patients is recorded.

Local anaesthetics

Local anaesthetics block the transmission of pain input from the site of insult to the spinal cord. This is one of the most complete types of pain relief. Local anaesthetics can be used in a nerve block alone or in combination with drugs such as alpha-2 agonists.

These drugs can also be injected into the tissue that has been incised or about to be incised, known as infiltration anaesthesia.

Local anaesthesia is an important component of multimodal analgesia, playing an important role in reducing perioperative and postoperative pain. Concern exists that directly injecting into the surgical site may lead to an increase in surgical site infection, but the few studies that have been published in the veterinary literature do not support this (Abelson et al, 2009; Andrews et al, 2023; Herlofson et al, 2023).

In fact, a long-acting bupivacaine has been licensed for use in cruciate surgery in dogs and onychectomy in the cat in the US (Nocita; Elanco Animal Health). The long-acting bupivacaine is a liposome-encapsulated injectable suspension. It is licensed to inject as the wound is closed with a 25g or larger needle. Smaller needles can disrupt the liposomes. The bupivacaine is released locally at the site of injection and breaks down over 72 hours.

The use of some form of local anaesthetic technique provides more complete analgesia, resulting in the following.

- Reducing the perioperative anaesthetic requirements.

- Reducing the opioid requirements perioperatively and postoperatively (Palomba et al, 2020).

- Better quality recovery from general anaesthesia.

- Improved postoperative pain control (Grubb and Lobprise, 2020).

Many techniques exist for nerve blocks which have been published in the literature.

Paracetamol

Paracetamol is licensed for use in the dog in the form of Pardale-V (Dechra Veterinary Products) for five days for acute pain of traumatic origin, and as a complementary treatment in pain associated with other conditions and postoperative analgesia.

The mode of action of paracetamol analgesia is not fully understood, with several mechanisms postulated. It is possible that it acts peripherally and centrally. Cholinergic, noradrenergic, opioid and serotonergic pathways may be involved. Even though this versatile drug has been available for many years, few controlled studies exist regarding its use in the acute and chronic setting.

The dose of paracetamol is quoted as 10mg/kg every eight hours in the BSAVA formulary. The licensed formulation of paracetamol combined with codeine (Pardale-V) is approximately 33mg/kg every eight hours for five days.

In a survey conducted in the UK, 98% of small animal vets had prescribed it during their career. As part of this, survey 80% of the vets did not experience any side effects. Many studies have been conducted at varying doses and for a wide range of conditions – Table 1 shows a selection of them.

| Table 1. Summary of paracetamol doses in research papers | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Paracetamol dose | Comparison groups | Surgery type | Outcome | Reference |

| 13mg/kg to 18mg/kg combined with hydrocodone 0.5mg/kg to 0.7mg/kg | Tramadol 5mg/kg to 7mg/kg | Tibial plateau levelling osteotomy | Similar pain scores. High rate of treatment failure in both groups | Benitez et al, 2015 |

| 15mg/kg IV then by mouth every 8 hours for 48 hours | Meloxicam 0.2mg/kg IV then 0.1mg/kg by mouth every 24 hours Carprofen 4mg/kg IV then by mouth every 24 hours |

Ovariohysterectomy | No significant differences between groups | Hernández-Avalos et al, 2020 |

| 20mg/kg | Saline | Ovariohysterectomy | No difference, study stopped | Leung et al, 2021 |

| 33mg/kg by mouth two hours before surgery then every 8 hours for 48 hours | Meloxicam 0.2/kg once and then 0.1mg/kg | Soft tissue and orthopaedic cases | Paracetamol non-inferior to meloxicam | Pacheco et al, 2020 |

The author uses paracetamol in patients that are not able to tolerate classic NSAIDs or where additional non-opioid analgesia is required. It may be that efficacy is affected by dose, timing of, frequency and route of administration.

Tramadol

Tramadol, along with other opioids, have increasingly been prescribed for “at home” medication over the past two decades (Clarke et al, 2019). A systematic review and meta-analysis of existing studies of postoperative pain relief (Donati et al, 2021) found that when compared to methadone or cyclooxygenase-2 inhibitors, the need for rescue analgesia was greater.

The level of evidence for postoperative analgesic effect of tramadol was low. It is licensed in the UK for mild acute and chronic soft tissue, and musculoskeletal pain. Chronic pain, usually because of OA, has been a common condition for which tramadol has been prescribed. Evidence for the efficacy is also mixed, and potentially it should not be used as a monotherapy for chronic pain (Domínguez-Oliva et al, 2021) in the dog.

Conclusion

Acute and chronic pain therapy continue to be a challenge for the general practitioner to treat.

Multimodal analgesic therapy will produce the most consistent results with the least side effects, and so, should be considered for all acute and chronic pain patients. Not all therapies will be pharmacological, and it is important to consider non-pharmacological therapies in acute and chronic pain.

The clinician should consider the type of pain the patient is presenting with when deciding on a treatment plan, and use some form of scoring system to allow tracking of the patient’s progress.

Each patient should be considered individually to establish the best course of treatment for the pet and the owner.

References

- Abelson AL, McCobb EC, Shaw S, Armitage-Chan E, Wetmore LA, Karas AZ and Blaze C (2009). Use of wound soaker catheters for the administration of local anaesthetic for post-operative analgesia: 56 cases, Veterinary Anaesthesia and Analgesia 36(6): 597-602.

- Alcalá AGDS, Gioda L, Dehman A and Beugnet F (2019). Assessment of the efficacy of firocoxib (Previcox) and grapiprant (Galliprant) in an induced model of acute arthritis in dogs, BMC Veterinary Research 15(1): 309.

- Andrews C, Williams R and Burneko M (2023). Use of liposomal bupivacaine in dogs and cats undergoing gastrointestinal surgery is not associated with higher rate of surgical site infections or multidrug-resistant infections, Journal of American Veterinary Medical Association 262(1): 1-6.

- Barale L, Monticelli P, Raviola M and Adami C (2020). Preliminary clinical experience of low-level laser therapy for the treatment of canine osteoarthritis-associated pain: A retrospective investigation on 17 dogs, Open Veterinary Journal 10(1): 116-119.

- Benitez ME, Roush JK, McMurphy R, Kukanich B and Legallet C (2015). Clinical efficacy of hydrocodone-acetaminophen and tramadol for control of postoperative pain in dogs following tibial plateau levelling osteotomy, American Journal of Veterinary Research 76(9): 755-762.

- Clarke DL, Drobatz KJ, Korzekwa C, Nelson LS and Perrone J (2019). Trends in opioid prescribing and dispensing by veterinarians in Pennsylvania, Journal of American Medical Association Network Open 2(1): e186950.

- Corral MJ, Moyaert H, Fernandes T, Escalada M and Tena JKS (2021). A prospective, randominzed, blinded, placebo-controlled multisite clinical study of bedinvetmab, a canine monoclonal antibody targeting nerve growth factor, in dogs with osteoarthritis, Veterinary Anaesthesia and Analgesia 48(6): 943-955.

- Corrêa JMX, Niella RV, de Oliveira JNS, Junior ACS, da Costa CSM, Pinto TM, da Silva EB, Beier SL, Silva FL and de Lavor MSL (2021). Antinociceptive and analgesic effect of continuous intravenous infusion of maropitant, lidocaine and ketamine alone or in combination in cats undergoing ovariohysterectomy, Acta Veterinaria Scandinavica 63(1): 49.

- Corrêa JMX, Soares PCLR, Niella RV, Costa BA, Ferreira MS, Junior ACS, Sena AS, Sampaio KMOR, Silvia EB, Silva FL and Lavor MSL (2019). Evaluation of the antinociceptive effect of maropitant, a neurokinin-1 receptor antagonist, in cats undergoing ovariohysterectomy, Veterinary Medicine International doi: 10.1155/2019/9352528.

- Costa RS, Hassur RL, Jones T and Stein A (2022). The use of pain scales in small animal veterinary practices in the USA, Journal of Small Animal Practice 64(4): 265-269.

- Cubeddu F, Masala G, Sotgiu G, Mollica A, Verace S and Careddu GM (2023). Cardiorespiratory effects and desflurane requirement in dogs undergoing ovariectomy after administration maropitant or methadone, Animals 13(14): 2,388.

- Domínguez-Oliva A, Casas-Alvarado A, Miranda-Cortés AE and Hernández-Avalos I (2021). Clinical pharmacology of tramadol and tapentadol, and their therapeutic efficacy in different models of acute and chronic pain in dogs and cats, Journal of Advanced Veterinary and Animal Research 8(3): 404-422.

- Donati PA, Tarragona L, Franco JVA, Kreil V, Fravega R, Diaz A, Verdier N and Otero PE (2021). Efficacy of tramadol for postoperative pain management in dogs: systematic review and meta-analysis, Veterinary Anaesthesia and Analgesia 48(3): 283-296.

- Grubb T and Lobprise H (2020). Local and regional anaesthesia in dogs and cats: Overview of concept and drugs (Part 1), Veterinary Medicine and Science 6(2): 209-217.

- Gruen ME, Lascelles BDX, Colleran E, Johnson J, Marcellin-Little D and Wright B (2022). 2022 AAHA pain management guidelines for dogs and cats, Journal of the American Animal Hospital Association 58(2): 55-76.

- Gruen ME, Thomson AE, Griffith EH, Paradise H, Gearing DP and Lascelles BDX (2021). A feline-specific anti-nerve growth factor antibody improves mobility in cats with degenerative joint disease-associated pain: A pilot proof of concept study, Journal of Veterinary Internal Medicine 30(4): 1,138-1,148.

- Herlofsen EAG, Tavola F, Engdahl KS and Bergstrom AF (2023). Evaluation of primary wound healing and potentials complications after perioperative infiltration with lidocaine without adrenaline in surgical incisions in dogs and cats, Acta Veterinaria Scandinavica 65(1): 21.

- Hernández-Avalos L, Valverde A, Ibancovichi-Camarillo JA, Sánchez-Aparicio P, Recillas-Morales S, Osorio-Avalos J, Rodríguez-Velázquez D and Miranda-Cortés AE (2020). Clinical evaluation of postoperative analgesia, cardiorespiratory parameters and changes in liver and renal function tests of paracetamol compared to meloxicam and carprofen in dogs undergoing ovariohysterectomy, PLoS One 15(2): e0223697.

- Kaneps AJ (2023). A one-health perspective: use of hemoderivative regenerative therapies in canine and equine patients, Journal of the American Veterinary Medical Association, 261(3): 301-308.

- Krautmann M, Walters R, Cole P, Tena J, Bergeron LM, Messamore J, Mwangi D, Rai S, Dominowski P, Saad K, Zhu Y, Guillot M and Chouinard L (2021). Laboratory safety evaluation of bedinvetmab, a canine anti-nerve growth factor monoclonal antibody, in dogs, The Veterinary Journal 276:105733.

- Leung J, Beths T, Carter JE, Munn R, Whittem T and Bauquier SH (2021). Intravenous acetaminophen does not provide adequate postoperative analgesia in dogs following ovariohysterectomy, Animals 11(12): 3,609.

- Marlin D (2023). Owners of dogs with arthritis perceptions of response to Librela, bit.ly/48h40T1

- Marquez M, Boscan P, Weir H, Vogel P and Twedt DC (2015) Comparison of NK-1 receptor antagonist (maropitant) to morphine as a pre-anaesthetic agent for canine ovariohysterectomy, PLoS One 10(10): e0140734.

- Michels GM, Honsberger NA, Walters RR, Tena JKS and Cleaver DM (2023). A prospective, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled multisite, parallel-group field study in dogs with osteoarthritis conducted in the United States of America evaluating bedinvetmab, a canine anti-nerve growth factor monoclonal antibody, Veterinary Anaesthesia and Analgesia 50(5): 446-458.

- Monteiro BP, Lee NH and Steagall PV (2023). Can cat caregivers reliably assess acute pain in cats using the Feline Grimace Scale? A large bilingual global survey, Journal of Feline Medicine and Surgery 25(1): 1098612X221145499.

- Murrell J (2014). Considerations and options for pain management in major surgery, Companion Animal 19(2): 88-93.

- Olsson DC, Teixeira BL, Jeremias T, Réus JC, Canto GD, Porporatti AL and Trentin AG (2021). Administration of mesenchymal stem cells from adipose tissue at the hip joint of dogs with osteoarthritis: A systematic review, Research in Veterinary Science 135: 495-503.

- Palomba N, Vettorato E, De Gennaro C and Corletta F (2020). Periperal nerve block versus systemic analgesia in dogs undergoing tibial plateau levelling osteotomy: Analgesic efficacy and pharmacoeconomics comparison, Veterinary Anaesthesia and Analgesia 47(1): 119-128.

- Pacheco M, Knowles TG, Hunt J, Slingsby LS, Taylor PM and Murrell JC (2020). Comparing paracetamol/codeine and meloxicam for postoperative analgesia in dogs: a non-inferiority trial, Veterinary Record 187(8): e61.

- Pittenger MF, Discher DE, Péault BM, Phinney DG, Hare JM and Caplan AI (2019). Mesenchymal stem cell perspective: cell biology to clinical progress, NPJ Regenerative Medicine 4: 22.

- Pye C, Bruniges N, Peffers M and Comerford E (2022). Advances in the pharmaceutical treatment options for canine osteoarthrtitis, Journal of Small Animal Practice 63(10): 721-738.

- Ross JM, Kleine SA, Smith CK, DeBolt RK, Weisent J, Hendrix E and Seddighi R (2022). Evaluation of the perioperative analgesic effects of grapiprant compared with carprofen in dogs undergoing elective ovariohysterectomy, Journal of the American Veterinary Medical Association 261(1): 118-125.

- Rousseau-Blass F, O’Toole E, Marcoux J and Pang DSJ (2020). Prevalence and management of pain in dogs in the emergency service of a veterinary teaching hospital, Canadian Veterinary Journal 61(3): 297-300

- Soares PCLR, Corrêa JMX, Niella RV, de Oliveira JNS, Costa BA, Junior ACS, Sena AS, Pinto TM, Munhoz AD, Martins LAF, Silva EB and Lavor MSL (2021). Continuous infusion of ketamine and lidocaine either with or without maropitant as an adjuvant agent for analgesia in female dogs undergoing mastectomy, Veterinary Medicine International 2021: 4747301.

- Storrer A, Mackie JT, Gunew MN and Aslan J (2023). Cutaneous lesions and clinical outcomes in five cats after frunevetmab injections, Journal of Feline Medicine and Surgery 25(1): 1098612X231198416.