16 Sept 2019

Companion animal dermatology

Jeanette Bannoehr discusses aural and dermal conditions that often present in cats and dogs, including management and diagnosis.

Image: Ermolaev Alexandr / Adobe Stock

Skin and ear conditions are often chronic processes that require long-term management. Owner compliance is crucial for treatment success and costs can become a limiting factor over time.

In dogs presented for a dermatological problem, pruritus is the most common clinical sign, whereas cats commonly present with cutaneous swellings (Hill et al, 2006).

Otitis, pyoderma, anal sac impaction, flea infestation and atopic dermatitis are frequent diagnoses in dogs, whereas abscesses, flea infestation and otitis dominate in cats (Hill et al, 2006). Ideally, the diagnosis is made early on to allow specific, rather than symptomatic, treatment and performing initial diagnostic tests might be more cost-effective in the long run.

This article gives an overview of basic and advanced dermatological workup, and summarises management options for common primary (allergy) and secondary (bacterial and yeast infection/overgrowth) skin diseases.

Approach

History taking

It is crucial to get a complete history for skin patients as the problem might be ongoing, and a number of previous investigations and treatments might have already been done. It is very true the history reveals a lot of useful information, but might also be time-consuming to acquire.

It might be helpful to have an owner questionnaire in the reception area, which owners can fill in while waiting summarising the most important information (Panel 1). Asking the owner for a numerical “itch and scratch” score (for example, 1 to 10) to rate the severity of pruritus (Colombo et al, 2005; Harvey et al, 2019) is also useful, especially to monitor clinical progression and treatment response between vet visits.

Thorough owner communication is essential to keep good compliance, and owners need to understand most skin conditions are chronic and require frequent follow-up appointments. Seeing the same clinician every time helps with case continuity and saves time reviewing the history.

1. Management

- Does your pet live only indoors or have access to outdoors?

- Does your pet have access to all rooms in the house and sit on the furniture?

- When did you last treat for fleas?

- Which product was used?

- Has your pet ever travelled abroad?

2. Food

- Nature of foodstuffs, including supplements?

- Is the appetite normal?

- Is there any weight loss/gain?

- Is the thirst normal/has it changed?

3. Contacts

- Are there any other animals in contact?

- Are they affected by the skin condition?

- Has any person in contact had a skin condition occurring around the same time as the pet?

4. General health

- Is your pet’s general health good?

- Any previous illnesses?

5. Skin problem

- When and at what age did the problem start?

- Are the symptoms worse at any time of year?

- Where on the body did it start?

- Has it spread or changed?

- Does your pet rub/scratch/chew/lick/bite?

- Was itching the first thing noticed

- Have there been any improvements, with or without treatment?

- What do you consider to be the major skin problem now?

Dermatological exam

In a busy practice setting, it is tempting to focus on the obvious lesions and/or owner’s main complaint. However, every dermatological patient should be fully examined in a systematic way by using a “head to tail” approach, including skin folds, paws (interdigital spaces and palmar/plantar aspects) and ventral abdomen. A full clinical examination helps to assess the general health of the patient and establish a differential diagnoses list for the skin complaint.

Further tests

Basic workup

Cytology

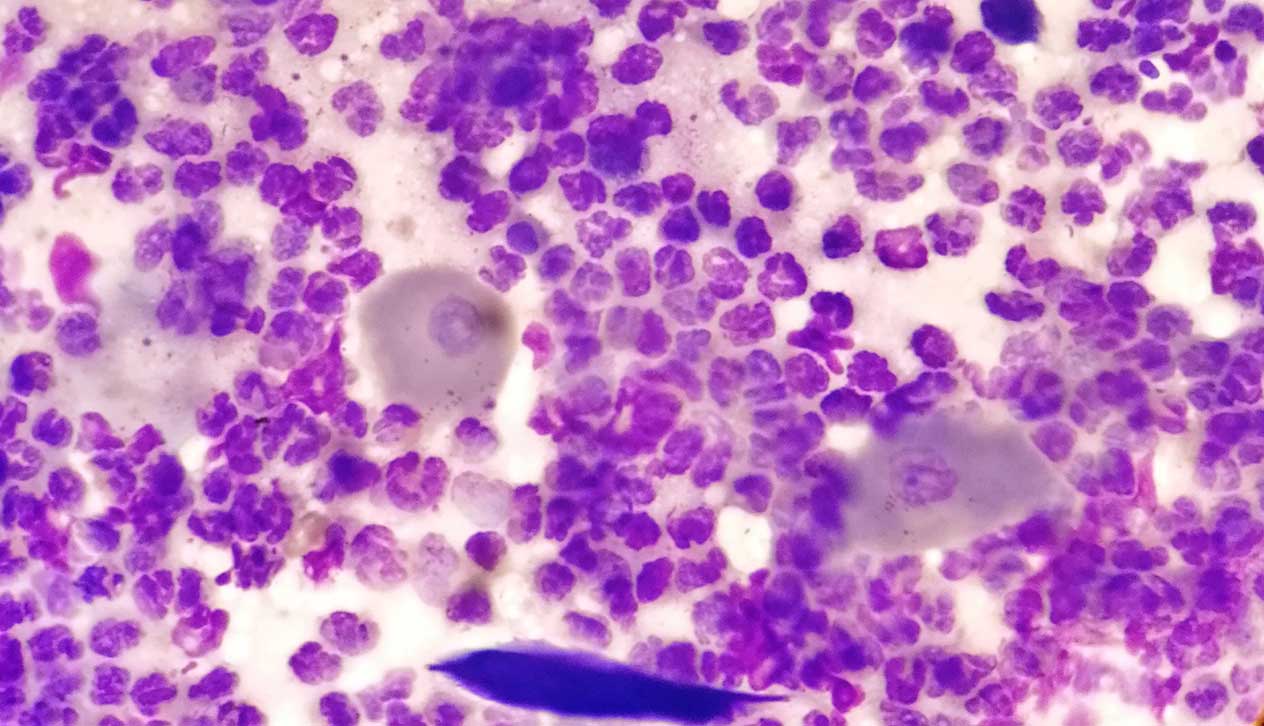

In-house cytology is a very rewarding, but often underused diagnostic tool in dermatology. It is quick, cost-effective, and gives valuable information about the presence of microorganisms and/or inflammatory cells.

A common scenario would be the allergic patient suffering a flare-up of pruritus, which could be due to the hypersensitivity condition, but also caused by secondary overgrowth/infection with yeast and/or bacteria; this could be readily distinguished on cytology (Figure 1; Bajwa, 2017).

Cytology is very valuable to differentiate between yeast, bacterial or mixed otitis, especially to detect the presence of rod-shaped bacteria, in which case, bacterial culture should be performed.

Repeating cytology at follow-up appointments can give important information about treatment response, whether prolonged therapy is indicated or whether the approach needs to be altered and/or potentially resistant bacteria have emerged, prompting the need for bacterial culture (see further on and Panel 2).

- Extent of lesions does not reduce by at least 50% within two weeks of systemic antibiotics.

- New lesions develop after two weeks or more on systemic antibiotics.

- Lesions have not completely resolved after six weeks of systemic antibiotics, and cocci are still seen on cytology.

- Rod-shaped bacteria are seen on cytology (intracellular).

- History of previous multidrug-resistant infection (patient or in-contact pets).

When to perform bacterial culture

The International Society for Companion Animal Infectious Diseases guidelines (Hillier et al, 2014) give five scenarios when performing bacterial culture is mandatory (Panel 2).

Flea comb, skin scrapes, hair plucks and fungal culture

Coat brushings, skin scrapes and hair plucks (trichograms) only require simple and affordable equipment, and should be part of the initial workup in any dermatological case. For example, a trichogram is useful to establish the presence of Demodex species (if a deep skin scrape is not feasible due to lesion location), but also to investigate for other conditions, such as self-inflicted alopecia/over-grooming (presence of broken hair shafts) or dermatophytosis (for example, fungal elements seen within hair shafts).

If even the slightest suspicion of dermatophytosis (clinical lesions can be highly variable, and do not always present as the classic “ring”; Figure 2) exists, fungal culture should be performed and, preferably, submitted to an external laboratory.

Advanced workup

When to perform skin biopsies

Skin biopsies can be useful for inclusion or exclusion of differential diagnoses and ideally to reach a definite diagnosis. However, biopsies are more invasive and costly than other diagnostic tests, and commonly require sedation or general anaesthetic. They should, therefore, be part of a logical workup process, rather than being “the single most informative test”, and timing and lesion selection is important.

Prior to taking skin biopsies, anti-inflammatory medications (especially oral glucocorticoids) should be discontinued for four weeks, and the patient assessed for secondary bacterial pyoderma and treated if needed, unless the patient’s condition does not allow for any delay.

Bacterial infection can significantly mask any underlying pathology and the histopathological changes seen may, therefore, not be representative.

Examples of skin conditions that require histopathological diagnosis include, among others, pemphigoid or lupoid diseases (Figures 3a and 3b), erythema multiforme, hair cycle disorders, sebaceous adenitis or any form of suspected cutaneous neoplasia.

When to perform allergy testing

Allergy remains a diagnosis made based on the patient’s history and clinical factors – it cannot be made by laboratory tests (Bajwa, 2018; Hensel et al, 2015; Olivry et al, 2015). It is a diagnosis of exclusion; other differential diagnoses with similar clinical presentation (for example, ectoparasites) need to be ruled out first.

In feline and canine allergic patients, flea allergic dermatitis and cutaneous adverse food reaction (“food allergy”) should be included or excluded prior to testing for environmental allergens.

Some patients suffer from more than one form of allergy – for example, a confirmed cutaneous adverse food reaction does not necessarily exclude atopic dermatitis.

To aid with making the diagnosis of canine atopic dermatitis (CAD), several sets of clinical criteria have been developed.

Most recently, Favrot’s criteria has been published and can be easily applied in practice (Favrot et al, 2010; Panel 3). However, the diagnosis of CAD is multifactorial and should not be based on those factors alone.

- Age at onset less than three years.

- Mostly living indoors.

- “Alesional” pruritus at onset.

- Affected front feet.

- Affected ear pinnae.

- Non-affected ear margins.

- Non-affected dorsolumbar area.

Testing for environmental allergens

Allergy testing for environmental allergens is indicated once the clinical diagnosis of CAD or feline atopy-like dermatitis has been established. The purpose of performing allergen serology and/or intradermal testing is allergen avoidance (wherever possible), and formulation of allergen-specific immunotherapy (ASIT; Bajwa, 2018; Gedon and Mueller, 2018).

- Dogs: prior to intradermal testing, oral and topical (for example, ear drops) glucocorticoids need to be discontinued for 14 days and antihistamines for 7 days. No withdrawal is required for ciclosporin A (Olivry et al, 2013). For allergen serology testing, short-acting oral glucocorticoids (at anti-inflammatory dosages for short time periods) and ciclosporin A do not need to be discontinued; no appropriate data is available for withdrawal times of topical glucocorticoids and antihistamines (Olivry et al, 2013). No recommendations exist to discontinue oclacitinib or lokivetmab prior to allergy testing.

- Cats: the author is not aware that similar detailed drug withdrawal times prior to allergy testing have been published for feline patients.

Testing for food allergy?

Performing strict elimination diet trials for several weeks to test for cutaneous adverse food reaction can be difficult for owners and their pets. Many owners are reluctant to “challenge” their animals with other food stuffs after, as this implies the risk of relapse or deterioration.

Serum testing for food-specific IgG and IgE is available and tempting; however, repeatability is low (Mueller and Olivry, 2017) and studies showing their value in reliably diagnosing “food allergy” are lacking. They might be helpful to choose the components for the food trial.

A strict elimination diet trial with a novel or hydrolysed food, for a minimum period of eight weeks, followed by provocation trials with other food stuffs, remains the gold standard to diagnose cutaneous adverse food reaction.

Treatment and management

Allergy

The allergic patient can often be successfully managed, but rarely cured. Treatment needs to be tailored to the individual, and consists of the combination of long-term measures and acute interventions when flare-ups occur.

The multimodal treatment approach includes symptomatic medications to relieve pruritus and inflammation, disease-modifying treatment (for example, ASIT), management of secondary bacterial, yeast overgrowth and infection, supportive measures to improve the skin barrier and avoidance of flare factors, if possible (Gortel, 2018).

For CAD and feline atopy-like dermatitis, ASIT is the only available disease-modifying treatment and is often recommended to be continued life-long if successful (Gedon and Mueller, 2018). Even though clinical response is slow and treatment success cannot be guaranteed, it might be more cost-effective than frequent symptomatic treatment in the long run.

For owners who are reluctant to consent to frequent SC injections, sublingual immunotherapy (SLIT) might be the more acceptable option. Treatment success rates were comparable in one study (DeBoer and Morris, 2012). SLIT can be successful in some cases that fail to respond to SC ASIT (DeBoer and Morris, 2012).

Sublingual immunotherapy for canine food allergy is an interesting area of research (Maina et al, 2019) and might become available in the future.

In cases of CAD where symptomatic treatment is needed, the main choices with proven clinical efficacy are glucocorticoids, ciclosporin A, oclacitinib and lokivetmab (Gortel, 2018; Olivry et al, 2015). The decision should be made on the individual patient’s needs as they all differ in their mode of action, onset and duration, potential side effects and costs. For example, glucocorticoids might be a good option for fast, initial short-term relief during allergy workup, whereas ciclosporin A might be chosen for patients that require long-term symptomatic treatment after workup has been completed and disease-modifying measures (for example, ASIT) have been unsuccessful or additional medications are needed. Oclacitinib and lokivetmab can be used for short-term and long-term management, but should not replace the initial workup.

All the aforementioned can be complemented by supportive therapies (for example, essential fatty acids or hypoallergenic shampoos).

Bacteria and yeast

Bacterial and yeast overgrowth, and infection, should always be considered secondary to an underlying pathology.

With the emergence of bacterial resistance, topical products are a valuable alternative to systemic treatment. Whenever possible, topical antimicrobial treatment is favoured over oral antibiotics and is usually well-tolerated.

Topical therapy is recommended as a single treatment for surface and superficial infections, especially for cases with meticillin-resistant Staphylococcus species (Morris et al, 2017).

One study has shown twice-weekly bathing with a 4% chlorhexidine digluconate shampoo in combination with daily 4% chlorhexidine digluconate solution was as effective as a course of oral amoxicillin-clavulanic acid over a four-week period (Borio et al, 2015).

Besides chlorhexidine-containing products, other antimicrobial topical treatments (for example, hypochlorous acid) are available and licensed for animal use.

In topical therapy, several factors (for example, presence of localised or generalised lesions, frequency of application, owner compliance, and the patient’s temperament and tolerance) contribute to therapeutic success.

Topical therapy can be maintained long-term to prevent relapses of overgrowth/infection (for example, antimicrobial shampoo therapy or ear cleaning) and might be less costly over time than repeated courses of systemic antimicrobial treatment.

Conclusions

Dermatological conditions are often chronic and can frequently be managed, but not cured. Good owner communication and compliance is crucial for treatment success.

Aiming for further workup and a clear diagnosis early on is beneficial, not only for the patient’s welfare and disease management, but also cost-effective in the long term.

References

- Bajwa J (2018). Atopic dermatitis in cats, Can Vet J 59(3): 311-313.

- Bajwa J (2017). Cutaneous cytology and the dermatology patient, Can Vet J 58(6): 625-627.

- Borio S, Colombo S, La Rosa G et al (2015). Effectiveness of a combined (4% chlorhexidine digluconate shampoo and solution) protocol in MRS and non-MRS canine superficial pyoderma: a randomized, blinded, antibiotic-controlled study, Vet Dermatol 26(5): 339-344.

- Colombo S, Hill PB, Shaw DJ et al (2005). Effectiveness of low dose immunotherapy in the treatment of canine atopic dermatitis: a prospective, double-blinded, clinical study, Vet Dermatol 16(3): 162-170.

- DeBoer DJ and Morris M (2012). Multicentre open trial demonstrates efficacy of sublingual immunotherapy in canine atopic dermatitis, Vet Dermatol 23(Suppl 1): 65.

- Favrot C, Steffan J, Seewald W et al (2010). A prospective study on the clinical features of chronic canine atopic dermatitis and its diagnosis, Vet Dermatol 21(1): 23-31.

- Gedon NKY and Mueller RS (2018). Atopic dermatitis in cats and dogs: a difficult disease for animals and owners, Clin Transl Allergy 8: 41.

- Gortel K (2018). An embarrassment of riches: an update on the symptomatic treatment of canine atopic dermatitis, Can Vet J 59(9): 1,013-1,016.

- Harvey ND, Shaw SC, Blott SC et al (2019). Development and validation of a new standardised data collection tool to aid in the diagnosis of canine skin allergies, Sci Rep 9: 3,039.

- Hensel P, Santoro D, Favrot C et al (2015). Canine atopic dermatitis: detailed guidelines for diagnosis and allergen identification, BMC Vet Res 11: 196.

- Hill PB, Lo A, Eden CAN et al (2006). Survey of the prevalence, diagnosis and treatment of dermatological conditions in small animals in general practice, Vet Rec 158(16): 533-539.

- Hillier A, Lloyd DH, Weese JS et al (2014). Guidelines for the diagnosis and antimicrobial therapy of canine superficial bacterial folliculitis (antimicrobial guidelines working group of the International Society for Companion Animal Infectious Diseases), Vet Dermatol 25(3): 163-175.

- Maina E, Devriendt B and Cox E (2019). Food allergen-specific sublingual immunotherapy modulates peripheral T cell responses of dogs with adverse food reactions, Vet Immunol Immunopathol 212: 38-42.

- Morris DO, Loeffler A, Davis MF et al (2017). Recommendations for approaches to meticillin-resistant staphylococcal infections of small animals: diagnosis, therapeutic considerations and preventative measures, clinical consensus guidelines of the World Association for Veterinary Dermatology, Vet Dermatol 28(3): 304-331.

- Mueller RS and Olivry T (2017). Critically appraised topic on adverse food reactions of companion animals (4): can we diagnose adverse food reactions in dogs and cats with in vivo or in vitro tests? BMC Vet Res 13(1): 275.

- Olivry T, DeBoer DJ, Favrot C et al (2015). Treatment of canine atopic dermatitis: 2015 updated guidelines from the International Committee on Allergic Diseases of Animals (ICADA), BMC Vet Res 11: 210.

- Olivry T, Saridomichelakis M; International Committee on Atopic Diseases of Animals (ICADA; 2013). Evidence-based guidelines for anti-allergic drug withdrawal times before allergen-specific intradermal and IgE serological tests in dogs, Vet Dermatol 24(2): 225-232.

Meet the authors

Jeanette Bannoehr

Job Title