14 Jul 2020

Companion animal parasite threats

Ian Wright discusses five ticks and tick-borne pathogens that have the potential to establish in the UK in the next decade.

Figure 1. An Ixodes ricinus tick.

Ticks and tick-borne pathogens represent an increasing risk to UK pets and their owners. This threat comes not just from those endemic in the UK, but also from those originating abroad.

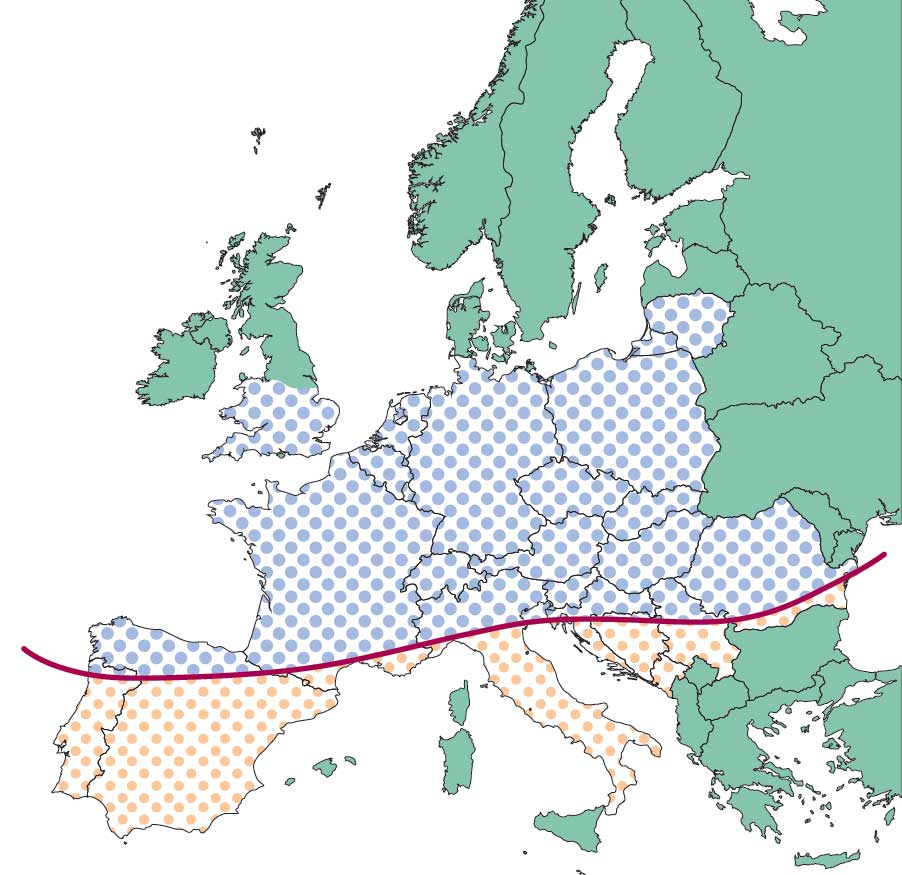

Changes in climate and habitat – in the face of increased pet travel and importation – has led to significant changes in European tick populations, and the UK faces the prospect of a range of novel ticks and their pathogens establishing in the UK.

This article takes five examples of ticks and their pathogens that could establish in the UK in the next decade. It also considers what the UK veterinary profession can do as part of the effort to turn back the tide, and keep pets and their owners safe.

Tick-borne disease is a growing risk to UK pets and their owners, with significant changes in the numbers and species of ticks and tick-borne pathogens being present in the UK over the past decade.

These changes are driven by a number of factors, including:

Increasing numbers of exotic ticks entering the country on travelled and imported pets.

- Increasing numbers of dogs infected with tick-borne pathogens entering the UK from abroad.

- Migratory birds carrying exotic ticks – these may then fall off their hosts and overwinter in the UK if the winter is mild. This is more likely to occur as climate change progresses.

- Changes in climate and increased forestation – a humid, warmer climate will allow ticks to remain active for longer periods and successfully overwinter. Increased green space and forestation will lead to increased wildlife hosts and overwintering environments for ticks.

These trends make the establishment of novel ticks and tick-borne pathogens in the UK more likely over time, with consequences for pet and human health.

Numerous different ticks and tick-borne pathogens could establish in the UK, but five of veterinary significance have already demonstrated potential to become endemic on a temporary or long‑term basis.

Preventing establishment of novel ticks and tick-borne pathogens

Factors are involved in the establishment of novel ticks and tick-borne pathogens – such as those introduced by migrating birds – that remain largely beyond the control of veterinary professionals.

Vets and nurses still have a vital role, however, in preventing establishment of emergent ticks and pathogens, and reducing the risk of their introduction.

This was demonstrated in the B canis outbreak, in which rapid coordination by local vets, diagnosis of local cases and raising awareness among the local dog-owning public helped to contain and possibly eliminate the outbreak.

Preventive measures that vets and veterinary nurses can employ include:

Advising tick prevention for pets at risk of tick exposure – the use of prophylactic compounds that rapidly kill or repel ticks are useful in reducing tick feeding and, therefore, transmission of infection. Products containing an isoxazoline or pyrethroid all fulfil these criteria. With the exception of Seresto, pyrethroid products must never be used on cats due to resultant toxicity. No product is 100% effective and owners should, therefore, still be advised to check their pet for ticks at least every 24 hours if possible.

Treatment of travelled and imported pets – to reduce the risk of exotic tick introduction.

Preventive tick treatment of dogs likely to spread ticks and pathogens from endemic foci – such as B canis in Essex and adjoining counties, or TBEV in the New Forest and Thetford Forest. This will reduce the risk of infected ticks being moved by dogs to new endemic areas and pets being exposed to potentially fatal tick-borne pathogens.

Checking imported, travelled and high-risk pets for ticks at least every 24 hours, and submitting those found for identification – this is essential to reduce the risk of exotic ticks entering the country, being moved from one region to another, and to protect pets from pathogen transmission. No tick preventive product is 100% effective and challenge in some geographical foci can be extremely high. Latest Tick Surveillance Scheme data has suggested the majority of ticks are located and found around the head, face, legs and ventrum (Wright et al, 2018). Ticks should be removed with a tick removal device or fine‑pointed tweezers. If tweezers are used, the tick should be removed with a smooth upward pulling action. If a tick hook is used, a simple “twist and pull” action is employed. After ticks have been removed, they should be submitted to the Tick Surveillance Scheme for identification. Public Health England is happy to receive ticks for identification. They should be placed in a container with a secure lid and sent in an envelope marked “biological sample” to: Tick Surveillance Scheme, Public Health England, Porton Down, Salisbury, Wiltshire SP4 0JG.

Additionally, the University of Bristol has an excellent tick identification website, www.bristoluniversitytickid.uk

Identifying ticks will help inform which pathogens pets may have been exposed to, geographical distribution of ticks and whether Rhipcephalus tick infestations may have established in households.

Vigilance for relevant clinical signs of tick-borne disease – recognising disease syndromes and relevant clinical signs for specific tick-borne pathogens will allow rapid diagnosis and identification of local outbreaks. Anaemia and thrombocytopenia, neurological signs, lymphadenopathy and pyrexia are common signs associated with tick-borne pathogens. A history of foreign travel, importation or visiting/living in endemic areas for specific tick-borne pathogens should raise suspicions further in pets presenting with relevant clinical signs.

Increasing public awareness – to relevant clinical signs, promoting the use of preventive tick products, vigilance for ticks and keeping away from outbreak hotspots. This will help limit the spread of pathogens and ticks, as well as improve prognostic outcomes for patients.

Conclusion

Exotic ticks and the pathogens they transmit are a growing threat to UK pets and the wider public.

A wide range of effective tick preventive products for cats and dogs are available, and essential to treat travelling, imported and high‑risk pets.

Awareness, though, of the rapidly changing tick presence in the UK, surveillance, and rapid identification of novel ticks and pathogens also remain vital if the establishment of exotic ticks and tick-borne pathogens are to be minimised.