4 Jul 2023

Sarah Caney BVSc, PhD, DSAM(Feline), MRCVS provides an overview for how vets can optimise options for a challenging and overlooked condition.

Image: © Sergey Khamidulin / Adobe Stock

Arthritis and osteoarthritis are terms often used to describe degenerative joint disease (DJD) affecting synovial joints. DJD is characterised by degeneration of the articular cartilage, hypertrophy of the bone at the articular margins and changes in the synovial membranes.

For many years, this has been an overlooked area of feline medicine – possibly since many challenges are associated with diagnosis. While awareness of arthritis has improved, DJD is still under-diagnosed and, therefore, under-treated in cats. A variety of often very successful therapeutic options are now available for DJD, making it more important than ever to diagnose arthritis in affected cats.

Keywords: DJD, arthritis, mobility, radiography, examination

Arthritis (and osteoarthritis) is defined as inflammation, or swelling of one or more joints, and is often used as a short-hand term for degenerative joint disease (DJD) affecting synovial joints. Both primary and secondary DJD occur in cats (Panel 1).

In older cats, idiopathic age-related degenerative changes in the joints are thought to be most commonly responsible for the arthritis. DJD is an irreversible and progressive condition.

Primary joint disease

Infectious causes; for example, bacterial polyarthritis.

Immune-mediated inflammatory diseases; for example, idiopathic polyarthritis.

Secondary joint disease

Congenital and developmental problems; for example, hip dysplasia.

Prior trauma resulting in joint instability; for example, fractures, ligament ruptures.

Several radiographic studies have shown that more than 90% of older cats have radiographic evidence of DJD in at least one joint. It is thought that at least 40% of these cats show clinical signs related to joint pain. The elbows, stifles and hips are most frequently affected, and this is often a bilateral condition affecting multiple joints.

A variety of therapeutic options exist, including analgesic medications, “mobility” diets and supplements alongside environmental modification to support affected cats.

In spite of the high prevalence of DJD in cats, it is still relatively under-diagnosed and, therefore, under-treated.

Traditionally, arthritis is diagnosed on the basis of clinical history, physical examination and radiographic changes. Cats aged 10 years and older are especially vulnerable to showing clinical signs associated with their DJD.

While clinical signs of arthritis are especially common in older cats, a recent study reported mobility changes in almost one-third of a cohort of 699 cats aged six years (Maniaki et al, 2021).

The study’s authors reported risk factors such as outdoor access, previous trauma and obesity that may predispose these younger cats to mobility changes associated with DJD.

Diagnosis of feline arthritis is challenging for a number of reasons. Firstly, since this typically is an insidious onset condition affecting multiple joints, affected cats do not present with obvious lameness. More typical is a gradual decline in activity levels and lifestyle/behaviour changes consistent with chronic musculoskeletal pain (Panel 2).

Unfortunately, many owners struggle to spot these gradual changes and may feel that it is normal for an older cat to be less active, and walk with a stiff gait, for example. The absence of a limp – since multiple joints and limbs are usually involved – may reduce a carer’s ability to recognise poor mobility. In cats that are otherwise well, often signs of reduced mobility are not seen as a priority reason for consulting a veterinarian. And in cats with concurrent diseases, often these are seen as “more important” than addressing subtler signs of chronic joint pain.

Carers are not always aware of existing treatment options and may presume that arthritis is just something that their cat has to put up with.

At the vet clinic, challenges diagnosing arthritis include difficulties assessing mobility in the consulting room. Physical examination and interpretation of joint palpation/manipulation is not always straightforward – especially in cats that are anxious and/or in pain. Affected joints may feel thickened or painful, and may have a reduced range of motion.

Radiographic confirmation of arthritis has traditionally been seen as an appropriate diagnostic test; however, a poor correlation between radiographic and clinical findings has been reported in a number of studies. For example, one study indicated one-third of joints painful on examination by an orthopaedic surgeon did not have any radiographic evidence of DJD, whereas a separate study showed radiographic evidence of DJD in around 20% of joints was not thought to be painful.

The most recent study of this nature indicated that while radiography could not confirm DJD with certainty, a normal range of

movement, absence of pain, crepitus, effusion and thickening tended to predict normal joints on radiography (Lascelles et al, 2012).

Computed tomography may be more reliable, but is expensive and typically requires general anaesthesia to perform – both of which are often barriers to clients.

Thorough history taking – ensuring the “right” questions are asked – can be extremely helpful in raising the suspicion of DJD. For example, it is helpful to ask about the cat’s enthusiasm and ability to jump up and down, and whether the height it is able to jump has reduced.

For many years, the author has used the questions included in Panel 2 with her clients.

Have there been any changes in a cat’s ability or enthusiasm to:

Have any of the following been noticed?

Have any of the following changes in your cat’s behaviour been detected?

Other miscellaneous questions

Formal mobility questionnaires, otherwise termed “clinical metrology instruments”, such as the feline musculoskeletal pain index (FMPI) developed by Duncan Lascelles and colleagues, have been validated for assessing impairment and monitoring cats with DJD.

The FMPI comprises 17 questions mainly relating to mobility, with questions also about grooming, eating, interactions with the carer and use of the litter box also included. Carers are asked to answer questions with answers ranging from normal to not at all, allowing a numeric score. The higher the score, the more normal or “less impaired” the cat is.

Recently, members of this research group have evaluated the sensitivity and specificity of each of these questions in screening cats for DJD-associated pain.

As an outcome to this research, a six-question checklist was produced, with the authors reporting sensitivity and specificity figures approaching 100% – especially when the screening questions are asked to carers with some previous experience of DJD in cats.

The six questions that were found to be most helpful were as follows; carers are invited to choose either “yes” or “no” for each:

Selecting “no” to one or more of the six questions was reported to have a 55% sensitivity and 97% specificity for identifying DJD pain when used as a screening test with owners not familiar with feline DJD (“DJD non-informed” owners). When used with owners that had some prior experience or knowledge relating to feline DJD (“DJD informed” owners), the sensitivity and specificity increased to 99% and 100% (Enomoto et al, 2020).

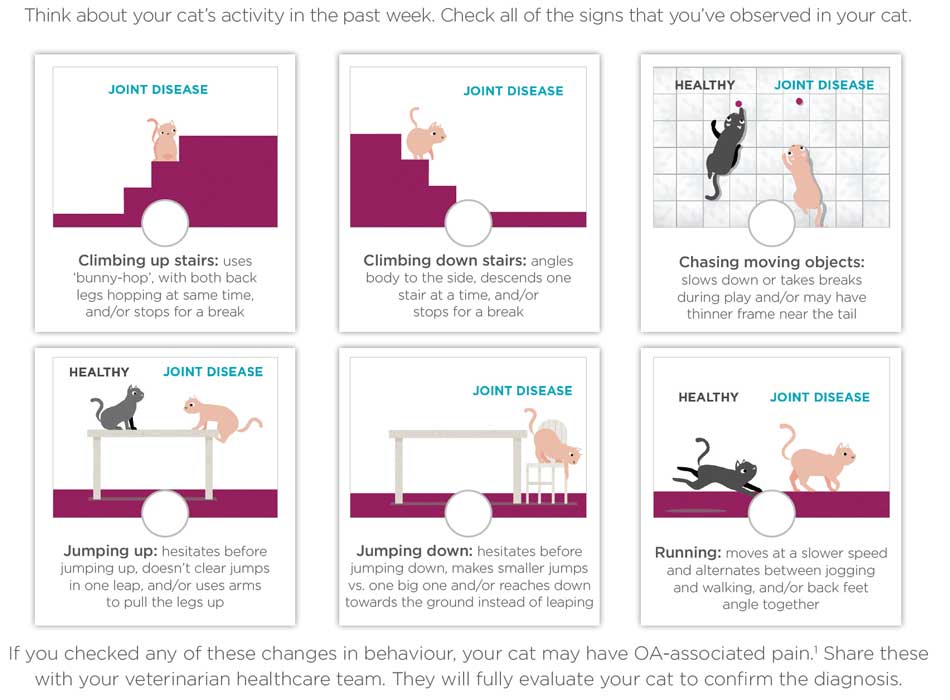

The authors suggest that these six questions are used as a screening tool, but if “no” is selected as an answer to any questions, a full mobility questionnaire – such as the FMPI (and/or the questions in Panel 2) – should be asked, and the cat closely examined and evaluated for the possibility of DJD (Figure 1).

The differing sensitivities reported for DJD-informed versus DJD non-informed owners suggest that education of carers could have an enormous impact on the utility of the checklist in clinical practice. It can be difficult for owners to know what is “normal” and what is not. Educational opportunities include owner discussions at preventive health care appointments and sharing videos of DJD versus healthy cats. Lascelles has developed a website that has a range of helpful graphics and other resources for owners at https://painfreecats.org

The author has found the questions posed in Panel 2 are also valuable in training carers of what clinical signs they should be looking out for.

In addition to the clinical history, observing the cat move is useful and can be facilitated by requesting home videos of the cat. A checklist for owners is shown in Table 1.

When reviewing footage, try to make notes not only on whether each activity was performed, but also how it was performed – taking into consideration the ease, enthusiasm and ability. Videos can be helpful in monitoring response to therapy. Similarly, it can be helpful to encourage owners to collect videos over time, so that progression of any mobility issues can be detected.

In clinic, mobility assessment is often tricky, but can be possible – especially if the clinic is quiet and “cat friendly”. Building steps into the side of the consulting room wall has facilitated some mobility observations in one clinic the author has worked in (Figure 2), and collecting video footage of patients coming down the steps can be useful in showing carers what signs of arthritis their cat is exhibiting. Cats with severe arthritis may walk with a stiff or stilted gait, and show hesitancy when coming down the steps.

An orthopaedic examination should be performed in cats suspected of having DJD. Supportive indicators of DJD include thickened joints, reduced range of movement and joint pain.

All nails should be assessed, since cats with reduced mobility are more vulnerable to thickened and overgrown nails, which can cause problems (Figure 3).

Reduced grooming can be manifested as a scurfy or matted coat, and chronic pain can result in a grumpier cat that is more resistant to handling.

In spite of limitations, radiography can be helpful in confirming arthritis.

While the author is generally reluctant to perform radiography solely for the rationale of confirming DJD, if imaging is indicated in an older cat, it is often helpful to include commonly affected joints (such as elbows or stifles) in standard radiographs of the chest and abdomen with the intention of looking for evidence of DJD (Figure 4).

Radiographic findings in patients with DJD include peri-articular and intra-articular new bone, narrowing of joint spaces, sclerosis of the subchondral bone, bone remodelling, soft tissue thickening/swelling around the joint and joint effusion.

Any of these radiographic changes should be interpreted as potentially significant – changes can be subtle, even in patients with marked DJD.

Fasted blood and urinalysis is indicated to look for concurrent problems such as renal disease, hyperthyroidism and diabetes mellitus, as these too are common in older cats and may impact on therapeutic decision making.

Mobility monitoring via collar-mounted “activity trackers” is becoming more sophisticated and this type of technology has been reported in some research studies.

Battery life of devices often limits long-term monitoring of activity levels, and a great degree of inter-cat variability has been reported (Gruen et al 2017; Yamazaki, 2020).

Nonetheless, it is likely that with advances in technology, more opportunities will arise for early diagnosis of arthritis, as well as therapeutic monitoring – for example, relating to treatment efficacy.

Pressure force plate and thermal sensitivity tests can offer some insight, although these tests are generally not available outside a research setting.

Diagnosis of arthritis remains challenging. Use of a short “mobility checklist”, such as the one discussed in this article, and education of carers as to the clinical signs of DJD should assist in diagnosis of more cases in the future.