12 Nov 2021

Dermatitis in canine patients

Diana Ferreira describes the diagnosis, treatment, prognosis and management of key dermatological and bacterial infections.

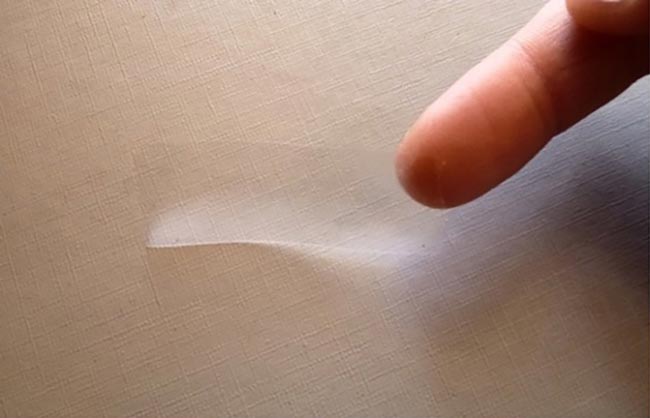

Figure 7. Example of localised lesions on the interdigital skin.

Skin infections in dogs are very common reasons for a veterinarian consultation.

Because the skin reacts in a limited way to different insults, a straightforward diagnosis is commonly not possible. For that reason, to properly diagnose the different conditions that could be responsible for one clinical presentation, it is crucial a thorough history is obtained, followed by a series of diagnostic tests.

These aid in the confirmation or exclusion of the differential diagnoses that were considered adequate for that particular clinical presentation.

In veterinary dermatology, the tests used are considered rather simple by the experienced practitioner; however, they may present a challenge for those who don’t handle samples on a daily basis. So that the maximum is taken out of these tests, it is crucial to obtain and handle the samples correctly.

Bacterial, yeast and fungal infections are among the most commonly identified skin infections in dogs. This article intends to guide clinicians in the steps to properly manage these conditions.

Pyoderma

Pyoderma is a bacterial skin infection and among the most common dermatological conditions found in dogs.

The most common aetiological agent of pyoderma in dogs, Staphylococcus pseudintermedius, exists as part of the normal cutaneous and mucosal microbiota of animals.

The skin of healthy individuals should not be susceptible to bacterial infections; therefore, any skin infection should be considered as a sign of some underlying skin, metabolic or immune alteration. If this underlying cause is not identified, the infection may respond more slowly or insufficiently to treatment and recur frequently.

The conditions most often the main cause of pyoderma include allergies, endocrine or immunosuppressive conditions, and parasitic (demodicosis) or infectious (dermatophytosis).

In dogs, skin infections can manifest clinically in a number of ways. Among them, the most common are bacterial folliculitis, exfoliative dermatitis, impetigo, pyotraumatic dermatitis, mucocutaneous pyoderma and deep pyoderma.

For a correct diagnosis of bacterial skin infection, cytology of the lesions should be performed. These will reveal the presence of intracellular bacteria.

Deep pyoderma, however, represents an exception because intracellular bacteria can be difficult to detect on cytology. Samples must be collected properly to obtain the expected results.

The different techniques for obtaining cytology samples are used according to the location and type of lesion1.

Cytology of exudative/purulent material is generally best obtained by directly printing or gently rubbing the glass slide on to the surface of the lesion. When scabs are present, it is important to obtain a sample of the skin underneath the scab. If a sample is taken from a pustule, it is recommended to first open the lesion with a 25.8G needle.

The tape technique is used for dry, scaly or anatomically difficult‑to‑access lesions, such as interdigital spaces or skin folds. A piece of tape is grasped at one end with the middle or index finger (Figure 1) and the sticky side adheres to the lesion to be sampled.

Pressure is applied with the thumb of the hand holding the tape (Figure 2). The tape is removed and reapplied to adjacent areas or the same area several times to increase the chances of finding secondary infectious organisms.

For staining, dip the tape into Diff‑Quik stain solutions I and II. Dipping in methanol (Diff‑Quik fixative reagent) removes the adhesive from the tape and, consequently, the sample.

Once properly coloured, the tape with the sticky side is placed on a slide.

Historically, for the treatment of pyoderma, empirical systemic antibiotic therapy based on clinical presentation was considered adequate, with emphasis on the selection of an appropriate antibiotic dose and duration of treatment2.

With the recent appearance of meticillin‑resistant bacteria, the approach to pyoderma changed – and confirmation of pyoderma by cytological analysis and bacterial culture assumes great importance to ensure a responsible use of systemic antibiotic therapy3.

Systemic antibiotics should only be used:

- if the diagnosis of bacterial infection is clear, through compatible clinical and cytological results

- if no adequate response occurred to an appropriate topical treatment

- in deep pyoderma

In all cases of superficial pyoderma, systemic antibiotic treatment can be substituted for topical antiseptic treatment. Antiseptics have a therapeutic efficacy comparable to that of systemic antibiotics and, furthermore, do not result in a selection of bacteria resistant to antibiotics. An example is shampoos containing 2% to 4% chlorhexidine (also in combination with miconazole)4,5.

The efficacy of a chlorhexidine shampoo, applied twice‑weekly combined with a daily chlorhexidine spray, has been shown to be comparable to oral amoxicillin-clavulanate in a four-week comparative study in 51 dogs5.

In the case of generalised pyoderma, the frequency of baths depends on the severity; however, a minimum of two or three baths per week is recommended.

When no adequate response to the initial topical approach occurs, a systemic treatment should be prescribed.

In this case, no suspicion or risk factors for antibiotic resistance exist (it is not a recurrent infection and no history of repeated antibiotic use exists), the antibiotic can be prescribed empirically. The first choice antibiotics in these cases are clindamycin, first-generation cephalosporins (cefalexin, cefadroxil), amoxicillin-clavulanic acid and trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole.

Antiseptic treatments (baths, cleaning of lesions) should also be continued while the antibiotic treatment is being carried out. These help to resolve lesions more quickly and can help shorten the duration of systemic treatment.

The following situations, as they indicate an increased risk of resistance to antibiotics, require bacterial culture:

- less than 50% reduction in the number of lesions after two weeks of systemic antibiotic treatment

- appearance of new lesions compatible with infection two weeks or more after starting antibiotic therapy

- presence of residual lesions with cytology compatible with infection at the end of treatment

- history of previous infection with a multi‑resistant bacterium in the animal in question or in an animal from the same family environment

In culture, it must be taken into account that for S pseudintermedius:

- Oxacillin (meticillin) determines the susceptibility to beta-lactams.

- Tetracycline is an indicator of susceptibility to doxycycline.

- Enrofloxacin determines susceptibility to fluoroquinolones.

- In case of infection by meticillin‑resistant S pseudintermedius, other antibiotics may be included in the panel: minocycline, rifampin and chloramphenicol.

Only when systemic treatment shows resistance to all first‑line antibiotics can second‑line antibiotics be chosen. These include doxycycline, minocycline, chloramphenicol, fluoroquinolones, rifampicin and aminoglycosides.

The duration of treatment will depend on the severity of the infection. Treatment of superficial pyoderma normally requires two to four weeks of treatment, and treatment should continue for seven days after all lesions have resolved.

In the case of deep pyoderma, treatment should be carried out for a minimum of six weeks and should be continued for at least two weeks after the resolution of the palpable lesions.

Dermatophytosis

Dermatophytosis is caused by a fungal infection of keratinised skin structures. The most frequently implicated fungal organisms are Microsporum canis, Microsporum gypseum and Trichophyton mentagrophytes.

In immunocompetent animals, dermatophytosis is a self-limiting disease, resolving spontaneously in weeks to months. Treatment is, however, always recommended with the aim of shortening the course of the disease, and preventing its spread to other animals and people.

Dermatophytes are transmitted through contact with infected hair or, to a lesser extent, through contact with fomites that contain fungal spores. Trichophyton species are usually acquired, directly or indirectly, through exposure to reservoir hosts (rodents or yours).

M gypseum, in turn, is a geophilic dermatophyte that inhabits the soil; therefore, the infection involves contact with soil containing these fungi.

Dogs most often exhibit the typical alopecic, scaly ring lesions with follicular papules and pustules. Other manifestations include symmetric facial folliculitis/furunculosis, mimicking an erythematous or foliaceous pemphigus, with a lesion mainly caused by T mentagrophytes (Figure 3). Pruritus is usually minimal or absent.

In cases of generalised infection, seborrheic dermatitis with an oily seborrhea may occur.

Dermatophyte kerion is a type of nodular, exudative, well-circumscribed furunculosis associated with infections with M gypseum or T mentagrophytes. It occurs as a solitary lesion on the face or on a distal limb (Figure 4).

Most tests for diagnosing dermatophytosis can be performed in the clinic. Correct sample collection and identification of the dermatophyte responsible for the infection are key steps for correct diagnosis and determination of the origin of the infection, respectively.

Wood’s lamp examination consists of UV light with a wavelength of 253.7nm that causes tryptophan metabolites from certain dermatophytes to emit a greenish-yellow colour. The great use of Wood’s lamp is the possibility of detecting infected hair for further culture and/or microscopic examination. Hairs that emit fluorescence must, for this purpose, be collected.

When Wood’s lamp is negative, one way to harvest infected hairs for culture is through the toothbrush method (Mackenzie technique). In this method, the animal’s hair is gently brushed with a sterile toothbrush, and hair, scales and dermatophyte spores collected.

Fungal culture is often considered as the “gold standard” diagnostic test for dermatophytosis; however, culture can also result in false positives and negatives.

PCR can also be used for diagnosing dermatophytosis, giving much faster results compared to fungal culture. It is highly sensitive, and one disadvantage is that it can detect fungal DNA in the absence of a true infection.

For an effective therapeutic management of dermatophytosis cases, it is essential to identify infection in all dogs in contact with the infected animal, and treat the environment.

Topical treatment should be performed in all cases of dermatophytosis. Focal lesions can be treated with clotrimazole or miconazole creams every 12 hours. In multifocal or generalised lesions, bathing twice a week with 2% miconazole and 2% chlorhexidine is indicated.

Cases in which systemic treatment is indicated include:

- cases where lesions are multifocal

- in long-haired animals

- when dealing with animals that live in multiple animal environments

- when no satisfactory response occurs to a purely topical approach

Itraconazole and terbinafine are the most effective and safe options for the treatment of dermatophytosis.

With itraconazole, elevations in liver enzymes sometimes occur. The dose ranges from 5mg/kg to 10mg/kg every 24 hours.

Pulsatile therapy can be performed. The dose of terbinafine is 30mg/kg to 40mg/kg every 24 hours. It appears to be well tolerated.

Griseofulvin is effective, but has far more potential adverse effects than itraconazole or terbinafine. It should, therefore, not be the first therapeutic option as it can result in severe gastrointestinal adverse effects and myelosuppression.

Ketoconazole and fluconazole are less effective treatment options, and ketoconazole has a greater potential to develop adverse effects. The ketoconazole dose is 5mg/kg to 10mg/kg every 24 hours.

The fluconazole dose is 5mg/kg every 24 hours and appears to be quite safe. However, inappetence, increased liver enzymes and hepatotoxicity can occur.

Environmental disinfection plays a very important role in the treatment of dermatophytosis because it minimises the risk of transmission to people and other animals, and minimises the transport of spores by fomites. The environment, however, represents an extremely rare source of infection.

Dermatophyte treatment is usually long to adequately eliminate the infection and minimise the risk of recurrence or spread to other animals or humans. Treatment should be continued until complete resolution of clinical signs and until the organisms can no longer be cultured from the animal’s hair.

In cases with high compliance with topical and systemic treatment recommendations, two consecutive negative fungal cultures may not be necessary to determine cure6.

Malassezia dermatitis

Malassezia pachydermatis is commensal on canine and feline skin, and in the external ear canal. Malassezia dermatitis is common in dogs and it is usually secondary to an ongoing skin disorder, predominantly hypersensitivities and endocrine diseases (especially hypothyroidism).

Malassezia dermatitis typically presents as a pruritic dermatosis. Dogs with generalised skin disease are erythematous; greasy; or waxy, scaly and crusty (Figure 5). They often have an offensive rancid or yeasty odour. Chronic cases can have marked lichenification and hyperpigmentation (Figure 6).

Localised lesions commonly occur on the muzzle, lips, ventral neck, axillae, ventral abdomen, medial hindlimbs, interdigital skin (Figure 7), perineum, in the external ear canal (Figure 8) and intertriginous areas.

Malassezia paronychia may occur in some cases. When paronychia is involved, reddish‑brown staining of the claws or hair is present (Figure 9).

The most useful technique for the diagnosis of Malassezia dermatitis is cytological examination through the acetate tape technique7. The clinical significance of an observed population varies depending on the anatomical site sampled, breed, sampling method and host immune status7.

Topical therapy is often effective; however, it can be difficult to perform in large dogs, dogs with long or thick coats, and elderly owners. A combination of topical and systemic therapy usually helps in achieving a rapid response to treatment.

Localised disease may be easily treated with the topical application of an antifungal product. Multifocal or more generalised cases are treated with total body applications of shampoos.

Strong evidence of efficacy is available only for the use of a 2% miconazole and 2% chlorhexidine shampoo, used twice‑weekly8. This may be considered to be the topical treatment of first choice, and when owners are able to apply the product effectively. Moderate evidence is available for a 3% chlorhexidine shampoo7.

When topical therapy is impractical or ineffective, oral azoles are can be used. Ketoconazole is used at 5mg/kg to 10mg/kg orally every 24 hours.

Itraconazole is more expensive, but has better tissue penetration and a longer half-life, allowing pulse dosing when long-term therapy is needed. Itraconazole is given at 5mg/kg to 10mg/kg orally every 24 hours, or pulse-dosed at 5mg/kg to 10mg/kg orally for the first two days of each week8.

Recurrent Malassezia dermatitis is common and may require maintenance topical treatments to avoid constant disease. These can be done on a once-weekly or twice‑weekly basis and for some cases, pulse dosing of oral azoles. The underlying disease should be identified and corrected to avoid recurrent disease.

Conclusion

Skin infections in dogs are common. A correct diagnosis can be rapidly obtained when the diagnostic tests are appropriately used.

Treatments for skin infections should be based always on the correct identification of the disease and should never be administered empirically based on clinical signs only, as these can often be non‑specific for a given disease.

- Some drugs are used under the cascade.