7 Nov 2023

Developing a system to measure functional mobility in dogs

Georgia Wells explains the approaches vets make to ascertain both flexibility and maneuverability in canine pets, and future assessment plans.

Image © ksuksa / Adobe Stock

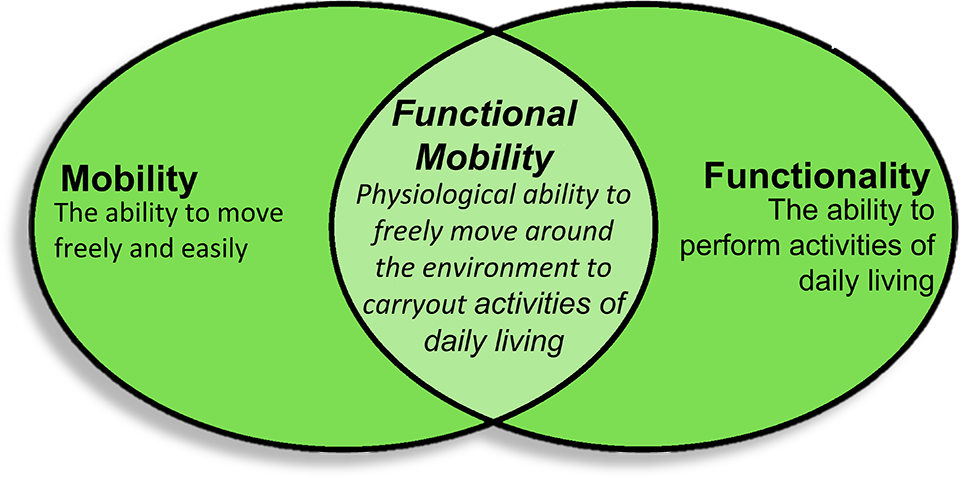

Mobility is defined as the ability to move freely and easily (Ramos and Otto, 2022). It is an essential element underlying the health and welfare of animals within the veterinary profession as changes to the animals’ mobility capabilities are commonly an indicator of an injury or disease.

For example, deviations from the animals’ normal range of movement may be the adaptive response to pain, or a mechanical dysfunction as a result of chronic or acute conditions affecting nerves, soft tissue, joints, bones or organs in one or more parts of the body (Hudson et al, 2004; Montalbano, 2022).

Alterations to mobility are perceived to impact quality of life; particularly when the functionality – the ability to perform activities of daily living (ADL) – is compromised (Warnes, 2015; Ramos and Otto, 2022; Bouça-Machado et al, 2020).

The combination of the terms mobility and functionality refer to the umbrella concept of functional mobility – defined as a patient’s physiological ability to freely move around their environment to carry out ADL (Figure 1; Bouça-Machado et al, 2020).

In human medicine, ADL typically include six factors: ambulation, feeding, dressing, toileting, continence and personal hygiene (Edemekong et al, 2022); however, a comprehensive list of ADL, backed by research, is yet to be established for dogs.

Canine mobility assessments in clinical practice

Within clinical practice, no standardised or widely recognised canine mobility assessment tool currently exists. Consequently, mobility assessments tend to be subjective, comprising of historical information reported by the owner on their pet’s ability to undertake daily activities, the observation of movement and gait, and the veterinary clinical examination. Even with a systematic approach to assess mobility, the lack of standardisation means assessments are imperilled to risk intra-observer and inter-observer variation (Montalbano, 2022).

Kinetic measures such as force plate analysis or pressure mat analysis can be used in clinic as part of a veterinary assessment as an objective, quantitative measure of limb function. However, although they objectively quantify limb loading, more complex problems, such as bilateral or multi-limb lameness, can be difficult to assess, and limb loading in isolation fails to capture the multidimensionality of mobility alone (Walton et al, 2013).

Despite these caveats, the veterinary examination is an important, cost-effective assessment of mobility issues. They permit the problems to be localised, medical interventions to be enacted and guide further diagnostic workups, such as targeted ancillary tests (Millis and Mankin, 2014).

Constraints to the assessment of mobility within the veterinary clinical examination exist. Firstly, the visualisation of the pet undertaking activities and the patient’s response to physical examination can only offer a one-off insight into the dog’s mobility capabilities on a given day.

In reality, mobility is a continuous trait that requires temporal context (Brown et al, 2013), which could be impacted by other factors such as activities done on a previous day. Therefore, for a temporal context to be established, assessments are partially reliant on owners accurately recalling detailed accounts of how the mobility problem presents and manifests on a daily basis. Additionally, the veterinary clinic environment often elicits a stress or excitement response in patients, which may impact behaviour or alter the expression of mobility or pain (Brown et al, 2013).

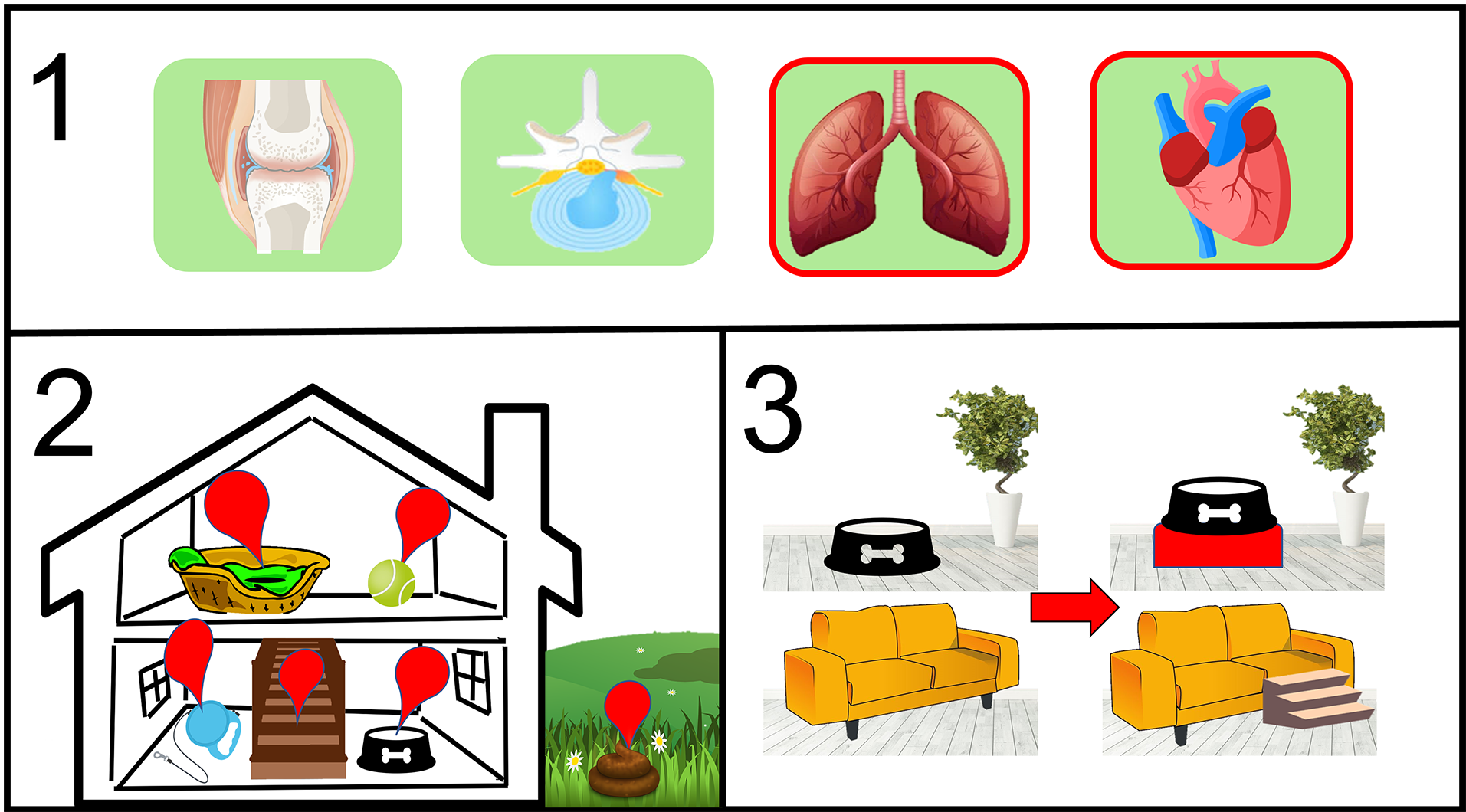

Importantly, time constraints and the environment limit the patient’s activities, which a veterinary professional can observe. For example, certain cardiovascular and respiratory diseases, such as congestive heart failure or canine idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis, compromise a dog’s ability to “freely and easily move” by restricting the distance the animal can walk before exhaustion (Boddy et al, 2004; Lilja-Maula et al, 2014), and cervical disc disease may inhibit a patient’s ability to put their head down to a food or water bowl (McKee, 2000).

Need for a functional mobility approach to mobility assessments

Arguably, a need exists to develop a standardised method of assessing mobility in dogs that can contextualise how a wide range of conditions impact a dog’s daily life – particularly beyond sole lameness. Considering this, the development of a system to focus on assessing functional mobility in practice would be useful (Figure 2).

It should be mentioned that various clinical metrology instruments (CMIs) have been produced and validated for use in canine veterinary medicine. CMIs are questionnaire-based measurements of health usually completed by owners, and many of these incorporate some level of functionality, or functional mobility assessment for canine patients. However, the commonly used CMIs at present quantify the level of pain, or the severity of a specific disease (typically OA) the dog is experiencing, rather than specifically measuring mobility (Alves et al, 2022).

Additionally, wearable technology is advancing and becoming increasingly popular for monitoring activity in dogs using accelerometers. Though currently clinical use is arguably premature, such technological advancements is allowing owners to track various parameters of their dog’s health, using complex algorithms to decipher between a dog at rest or in a form of “active” state (Väätäjä et al, 2018). Evidently, this is important for objectifying canine activity; however, activity is only one segment of the overall concept of functional mobility.

Also, while they may be able to collect a range of data relating to time spent performing an activity, number of times an activity was performed or distance moved, the quality of the movements involved in the activity performed cannot be assessed. Furthermore, little scientific evidence has been published assessing the validity of commercially available activity monitors (Belda et al, 2018), therefore further evidence is needed for them to be valid for use in veterinary medicine.

The development of a standardised systematic functional mobility assessment tool would go beyond current methods of assessing mobility as it would allow for:

- a more objective approach to assessing mobility, reducing intra-observer and inter-observer variation

- mobility assessments beyond lameness or gait abnormalities, giving scope to assess how mobility is compromised through injury or disease

- the evaluation of how a dog’s mobility problem impacts their ADL or life and the impact that disease progression or treatments have on this

- the identification of specific environmental modifications based on what activities a dog is finding challenging to aid the performance of AD

What’s next for canine functional mobility?

Researchers from SRUC and the University of Edinburgh Royal (Dick) School of Veterinary Studies are looking to enhance current mobility assessments. By taking an objective approach through consulting stakeholders, they set out to define what activities should be categorised as ADL for dogs and determine how healthy or diseased dogs perform these ADL.

The overarching aim of this research is to use the data to develop and validate a scale to measure functional mobility in dogs, capable of identifying changes to a dog’s ability to perform everyday activities over time.

Summary

Mobility is an important facet to canine health and welfare as changes to a dog’s ability to move freely and easily can often be an indicator of disease or injury. Current mobility assessment methods are limited to subjective clinical veterinary examinations.

Although these are a cost-effective insight into mobility, their capacity to holistically assess mobility is limited. To combat this, researchers are working on developing a scale to systematically measure functional mobility in dogs. Overall, a functional mobility assessment tool would be advantageous in assessing mobility beyond lameness by establishing how conditions impact a dog’s ability to perform a variety of everyday activities.

References

- Alves JC, Santos A, Jorge P, Lavrador C and Carreira LM (2022). Evaluation of four clinical metrology instruments for the assessment of osteoarthritis in dogs, Animals: An Open Access Journal from MDPI 12(20): 2,808.

- Belda B, Enomoto M, Case BC and Lascelles BDX (2018). Initial evaluation of PetPace activity monitor, Veterinary Journal 237: 63-68.

- Boddy KN, Roche BM, Schwartz DS, Nakayama T and Hamlin RL (2004). Evaluation of the six-minute walk test in dogs, American Journal of Veterinary Research 65(3): 311-313.

- Bouça-Machado R, Duarte GS, Patriarca M, Castro Caldas A, Alarcão J, Fernandes RM, Mestre TA, Matias R and Ferreira JJ (2020). Measurement instruments to assess functional mobility in Parkinson’s disease: a systematic review, Movement Disorders Clinical Practice 7(2): 129-139.

- Brown DC, Bell M and Rhodes L (2013). Power of treatment success definitions when the Canine Brief Pain Inventory is used to evaluate carprofen treatment for the control of pain and inflammation in dogs with osteoarthritis, American Journal of Veterinary Research 74(12): 1,467-1,473.

- Edemekong PF, Bomgaars DL, Sukumaran S and Schoo C (2022). Activities of daily living. In StatPearls, StatPearls Publishing.

- Hudson JT, Slater MR, Taylor L, Scott HM and Kerwin SC (2004). Assessing repeatability and validity of a visual analogue scale questionnaire for use in assessing pain and lameness in dogs, American Journal of Veterinary Research 65(12): 1,634-1,643.

- Lilja-Maula LIO, Laurila HP, Syrjä P, Lappalainen AK, Krafft E, Clercx C and Rajamäki MM (2014). Long-term outcome and use of 6-minute walk test in West Highland White Terriers with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis, Journal of Veterinary Internal Medicine 28(2): 379-385.

- McKee M (2000). Intervertebral disc disease in the dog 1, pathophysiology and diagnosis, In Practice 22(7): 355-369.

- Millis DL and Mankin J (2014). Orthopedic and neurologic evaluation. In Canine Rehabilitation and Physical Therapy, Elsevier, St Louis: 180-200.

- Montalbano C (2022). Canine comprehensive mobility assessment, The Veterinary Clinics of North America: Small Animal Practice 52(4): 841–856.

- Ramos MT and Otto CM (2022). Canine mobility maintenance and promotion of a healthy lifestyle, The Veterinary Clinics of North America: Small Animal Practice 52(4): 907-924.

- Väätäjä H, Majaranta P, Isokoski P, Gizatdinova Y, Kujala MV, Somppi S, Vehkaoja, A, Vainio O, Juhlin O, Ruohonen M and Surakka V (2018). Happy dogs and happy owners: Using dog activity monitoring technology in everyday life, Proceedings of the Fifth International Conference on Animal-Computer Interaction, Atlanta, Georgia.

- Walton MB, Cowderoy E, Lascelles D and Innes JF (2013). Evaluation of construct and criterion validity for the “Liverpool osteoarthritis in dogs” (LOAD) clinical metrology instrument and comparison to two other instruments, PloS One 8(3): e58,125.

- Warnes C (2015). Changes in behaviour in elderly cats and dogs, part 1: causes and diagnosis, The Veterinary Nurse 6(9): 534–541.