13 Oct 2021

Diagnosing lameness – ‘a science of uncertainty and an art of probability’

Ross Allan explores what should be considered when reaching a diagnosis of this common small animal presentation.

Image: VetCT

“A science of uncertainty and an art of probability” is how William Osler (1849-1919), one of the most respected clinicians in the history of the medical profession, described medicine. But could his description also be appropriate for how the veterinary team should approach and investigate lameness in our patients?

Lameness is a common presentation in small animal practice, with one large population study reporting 8.64% of dogs having a musculoskeletal diagnosis within a primary veterinary care setting in the UK (O’Neill et al, 2021).

Musculoskeletal diagnoses are therefore common – we make them every day. But “diagnosis” implies certainty and the infallibility of the professional. Is this really what we can achieve?

This article aims to explore what should be considered in reaching a diagnosis and the concept of probability as a factor that often persists in those we make.

Background

First, let us take a step back. We have all been taught to consider three pieces of clinical data to make any accurate diagnosis: the patient history, physical examination findings and diagnostic test results. These help us form a list of differentials and then systematically filter down to our diagnosis (Englar, 2019).

This system is drummed into us at vet school and has stood the test of time, but we should consider other elements that impact on an accurate diagnosis and review whether this “traditional” approach might, at times, predispose us to miscalculations.

How can you know your diagnosis is correct?

History taking

The first element to consider is our prioritisation of the information we get from owners. One author describes that in human health care, the patient history is what carries the greatest weight for us making our diagnosis (Englar, 2019). Is this what you do? Is this still how you work?

For many of us, our client interactions have changed during lockdown, and we have, therefore, adapted how we make our diagnoses. We still take a history and speak to the client, but the assessment of the patient in a consulting room with the client present has been less common and many vets have said the client’s absence did, perhaps, make the consult more efficient and effective than usual (personal communication).

Was this perhaps because we were more efficient at taking a succinct history or less inclined to talk? Was this observation about our changed behaviour positive or perilous? What did it mean for the accuracy of our diagnoses, and did that matter?

What do humans do?

It is well established that human doctors get diagnoses wrong. “Standardised patient” studies (where a “secret shopper” known medical diagnosis is used) has been shown to demonstrate an error in diagnosis of 13% to 15% (Graber, 2013) while, on “second reviews” of visual information (such as radiography or pathology) what is described as a “missed critical abnormality” that has not been picked up on initial assessment is detected in 2% to 5% of patients (Graber, 2013).

Some may argue that studies like these could be part of the problem: an inherent assumption exists that patients present with one problem to diagnose, whereas in real life they present with an array of deviations from “normal”, which we have to unpick and relate to their quality of life, as determined by the holistic presentation.

The studies that described these errors have, however, led those working within human health to start to investigate what factors lead to these misdiagnoses and explore the steps that can be taken to minimise/prevent them. Which of these may be transferable to veterinary medicine and should be undertaken more frequently? Can we learn from them?

“Clinicians make decisions in the face of uncertainty” (Cahan et al, 2003).

Do we need to adapt our professional narrative?

A concept stated in one human paper is that a “clinical diagnosis is more akin to the work of a detective than a scientist” (Trimble and Hamilton, 2016). This means risks exist in arriving at any diagnosis – we know that detectives can get their investigations wrong.

We therefore must consider what these risks are and how best to mitigate their potential to impact on reaching a correct diagnosis.

History taking

The first consideration is what historian Carl Trueman stated as “history is the remembered past” – it is therefore influenced by those who do the remembering (Graber, 2013). We all have individualised experiences, and recollections, of “reality”.

Asking leading questions and rephrasing these questions can all change the story we get. This isn’t to criticise owners, or clinicians – it’s to highlight this risk. Patience, sense checking and repeating back to owners, as well as careful consideration of how to phrase your questions, is key to try to make the clinical history as “true as can be remembered”.

Hypothetic diagnosis – how and why we test it

What matters in making clinical diagnoses is not only what the diagnosis is, but the steps we take to arrive at that diagnosis.

During professional training we are taught the importance of creating a full differential list and gradually performing tests to narrow this down, but we all know we don’t do this all the time.

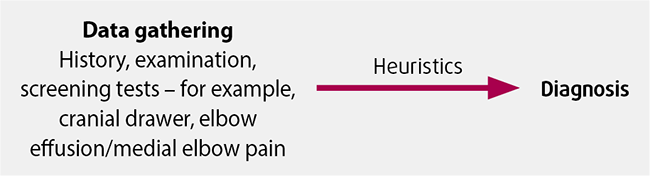

Anyone who has been in practice for more than a few months will, necessarily, start changing how they approach the frequent presentations. We naturally feel that we have made enough of the common diagnoses and this confidence, alongside the time and financial limitations we face, means we invariably start to predict the diagnosis based on the “shape” of the presentation (Figure 1).

While this usually works, and is a skill that typifies experience and confidence in the consult room, it also has dangers of “making diagnoses fit”, thereby increasing the risk of misdiagnosis.

For this reason, it is important for us all to “test” these assumed diagnoses and refine our heuristics. Some diagnoses will be different to what you assume and it’s important to periodically review whether you are correct, as well as checking the correct response to treatment – the latter being an essential element of every diagnosis.

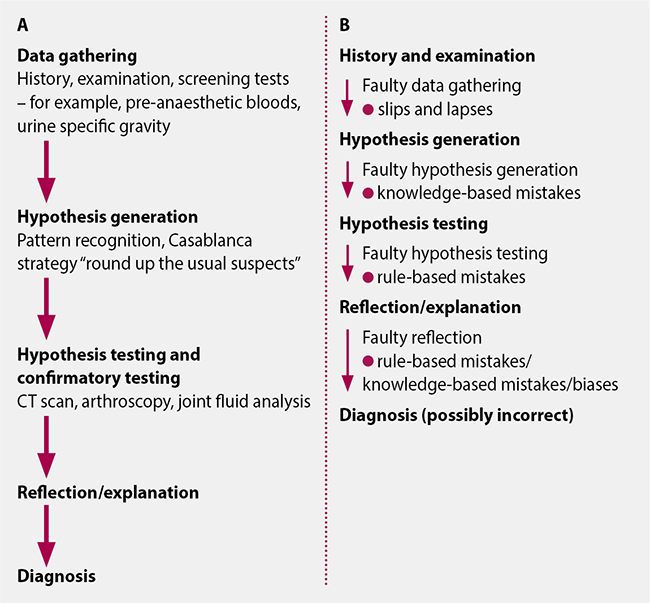

The more involved process of comprehensive hypothesis generation, testing and confirmatory testing does reduce the risks of misdiagnosis, but does not prevent it entirely. Risks still remain and can still result in a misdiagnosis (Figure 2).

These issues that remain highlight the awareness in human medicine that any diagnosis can still be incorrect – the risks remain, even if comprehensive steps are taken.

History

Dexter, a 5.5-year-old 55kg male cross-breed, presented with an acute onset hindlimb lameness after slipping on ice. On clinical examination he had a non-weight bearing lameness and was referred for likely cruciate surgery.

Assessment

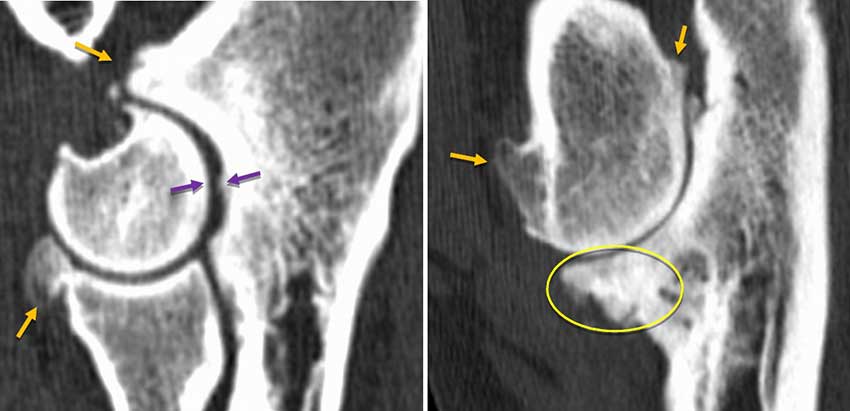

On examination Dexter had some stifle pain and resented attempted cranial drawer, but no drawer was present. X-rays showed lucency in the proximal tibia with a suspected compressive fracture of the tibial plateau and evidence of a visible Codman’s triangle – changes all highly suggestive of osteosarcoma (Figure 3).

Learning point

In the author’s personal experience, 1% of the past 300 “cruciate ligament” referrals have been hindlimb lamenesses confirmed as being due to osteosarcomas. There may be various factors in this: often early radiographic changes can be mild and have progressed/become more apparent by time of referral assessment. Similarly, with around 70% of ”cruciate” referrals arriving without any pre-assessment x-rays (personal communication), it is inevitable other causes such as osteosarcoma will be picked up.

What is perhaps relevant with this patient is the narrative approach taken with the owners – phrases such as “most likely the diagnosis is…” and “there are other possible causes that require more investigation, but on balance this will most likely be…”. Should we perhaps use these phrases more? Would emphasising the probability in the clinical diagnosis be beneficial and reduce risk of owners being disappointed with what they may see as a “missed” diagnosis?

History

His owner reported that Jack, a seven-year-old Labrador retriever, was stiff – especially on his back legs and after longer walks. Jack’s elbows felt thickened and had a reduced range of motion, and he had a bilateral forelimb lameness.

Assessment

A CT scan of his elbows showed significant changes typical of elbow dysplasia with moderate secondary OA. Jack responded slightly to conservative treatment (NSAIDs and exercise modification), but on review he was still stiff and seemed reluctant to lift his feet when walking.

A thyroxine/thyroid-stimulating hormone blood sample confirmed Jack to be hypothyroid. He responded dramatically to oral levothyroxine treatment, suggesting that neuromuscular pain (as is often reported to be a symptom of hypothyroidism in people) was likely a significant factor in his lameness. OA, while present and relevant, might not be the only cause for lameness (Figure 4).

Learning point

Jack highlights a key “danger” of “simple” diagnosis. Economical and succinct explanations with the fewest assumptions (Occam’s razor) will often be correct (such as a stiff dog having elbow OA), but more complicated solutions can also prove to be correct, and therefore need to be considered. Jack illustrates the importance of the counter-argument commonly known as Hickam’s dictum (often stated as “patients can have as many diseases as they damn well please”) and its place in clinical diagnosis (Jacob, 2015).

For Jack a pre-scheduled follow-up, reviewing the response to treatment and “testing” the other possible causes for the symptoms resulted in a successful outcome.

Conclusion

“Medicine is a science of uncertainty and an art of probability” – William Osler. When making any assertion about the likely diagnosis we almost inevitably talk about and use the language of probability. As one human doctor said, this “creates the veneer of something objective and scientific, but we really conceal greater uncertainty and error” (Upshur, 2013).

These risks in reaching the correct diagnosis are compounded by the inevitable challenges we face in clinical practice:

- The time to take a full history/assessment versus the available consult length.

- Clinical relevance of the history versus the history that the owner remembers and gives us.

- Which diagnostics that would help to reach a diagnosis versus the time, finances and facilities we have access to.

- Positive and negative predictive value of the tests we perform.

All of these elements, compounded by the potential for the presence of multiple undiagnosed diseases, emphasises the importance of considering “probability” as you reach a diagnosis. Are you right, could you be wrong and how will you check?

“Let’s see you back in two weeks to see how things are going” – it’s a good first step.

References

- Cahan A, Gilon D, Manor O and Paltiel O (2003). Probabilistic reasoning and clinical decision-making: do doctors overestimate diagnostic probabilities? QJM: An International Journal of Medicine 96(10): 763-769.

- Englar RE (2019). The role of the comprehensive patient history in the problem-oriented approach. In Common Clinical Presentations in Dogs and Cats, Wiley-Blackwell, Hoboken: 11-18.

- Graber ML (2013). The incidence of diagnostic error in medicine, BMJ Quality and Safety 22(Suppl 2): 21-27.

- Jacob KS (2015). The challenge of medical diagnosis: a primer on principles, probability, process and pitfalls, Ugeskrift for Laeger 28(1): 24-28.

- O’Neill DG, James H, Brodbelt DC, Church DB and Pegram C (2021). Prevalence of commonly diagnosed disorders in UK dogs under primary veterinary care: results and applications, BMC Veterinary Research 17(1): 1-14.

- Trimble M and Hamilton P (2016). The thinking doctor: clinical decision making in contemporary medicine, Clinical Medicine, Journal of the Royal College of Physicians of London 16(4): 343-346.

- Upshur REG (2013). A short note on probability in clinical medicine, Journal of Evaluation in Clinical Practice 19(3): 463-466.