1 Apr 2025

Diagnosis and management of mitral valve disease in dogs

Luca Ferasin DVM, PhD, CertVC, PGCert(HE), DipECVIM-CA(Cardiology), GPCert(B&PS), FRCVS and Heidi Ferasin BVSc, CertVC, MRCVS consider what has changed in the past five years of understanding and managing this cardiac disease.

Image: katamount / Adobe Stock

Myxomatous mitral valve disease (MMVD), or simply “mitral valve disease”, is a chronic degenerative disease resulting in deformation of the mitral valve with subsequent malapposition of its leaflets, which allows blood to flow backwards into the left atrium during cardiac contraction (mitral regurgitation; MR), producing a typical systolic heart murmur.

The tricuspid valve is also commonly concomitantly affected, with an associated tricuspid regurgitation; therefore, some clinicians prefer to refer to this condition as atrio-ventricular valve degeneration. The disease primarily affects geriatric, small-breed dogs, but it can also be diagnosed in larger breeds and younger individuals.

This article reviews the most recent information on diagnosis and management of this important cardiac disease, including current recommendations for medical therapies and surgical interventions.

Diagnosis and staging of MMVD

Diagnosis

Presumptive diagnosis of MMVD is relatively straightforward, based on signalment (geriatric, small-breed dog) and the presence of a newly developed systolic heart murmur with a point of maximum intensity over the left apex.

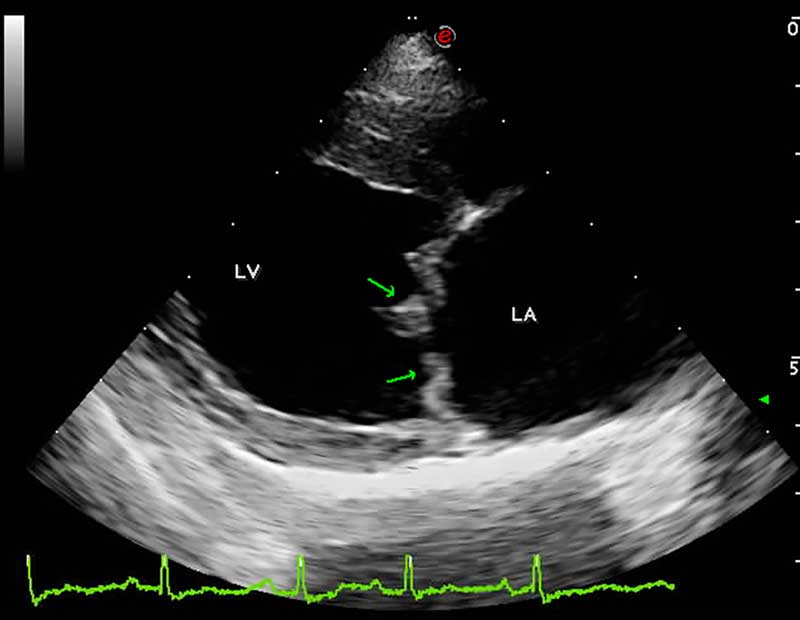

However, definitive diagnosis requires the visualisation of mitral valve lesions on echocardiographic examination (thickened, redundant and distorted leaflets; Figure 1) in association with the direct evaluation of systolic mitral valve prolapse and valvular incompetence (MR) by colour and spectral Doppler. Therefore, in the absence of all these echocardiographic features, the sole visualisation of mitral valve regurgitation on colour Doppler should not be considered sufficient for a definitive diagnosis of MMVD, and other pathologies should also be considered in the list of differential diagnoses.

ACVIM staging system

The American College of Veterinary Internal Medicine (ACVIM) Consensus Statement for the diagnosis and treatment of MMVD in dogs developed a staging system to classify the severity of MMVD for prognostic purposes and to facilitate treatment decisions, mainly based on radiographic and/or echocardiographic findings (Keene et al, 2019).

Therefore, physical examination alone may represent an important limitation; although, it has been previously demonstrated that the loudness of the heart murmur on thoracic auscultation in small breed dogs can provide very useful information (Ljungvall et al, 2014).

Indeed, clinicians can often confidently exclude congestive heart failure (CHF) or even severe disease in dogs with soft murmurs caused by MMVD. Therefore, if clinical signs such as dyspnoea and/or tachypnoea are present in a small-breed dog with a soft murmur, the attending clinician should certainly investigate potential causes other than CHF.

Although the likelihood of CHF and pulmonary hypertension increases with louder or even thrilling murmurs (traditionally graded as four out of six, five out of six and six out of six, according to the Levine scale), such murmurs are not definitive proof of severe disease. Therefore, small-breed dogs with moderate or loud apical murmurs caused by MMVD require further investigation to accurately determine the disease severity and clinical status.

The ACVIM staging system for MMVD describes four basic stages of the disease, indicated with the progressive letters of the alphabet.

Stage A includes healthy dogs that are at risk for developing MMVD, but do not yet have any structural heart abnormalities. This stage typically encompasses breeds that are genetically predisposed to MMVD, such as the cavalier King Charles spaniel, dachshund, and miniature poodle. Although including healthy dogs in the staging of MMVD may appear counter intuitive, this stage should serve as a reminder for clinicians that predisposed dogs should be regularly monitored, initially just with cardiac auscultation, to allow early detection of the disease.

Stage B encompasses dogs with a heart murmur secondary to MMVD that have never developed clinical signs caused by heart failure, and it can be further classified in two stages.

Stage B1 involves dogs with a characteristic heart murmur indicating mitral valve regurgitation, but without radiographic or echocardiographic evidence of cardiac enlargement. At this stage, dogs remain asymptomatic, and their quality of life is mostly unaffected. Annual cardiac assessments are recommended to monitor the progression of the disease.

Conversely, dogs in Stage B2 show signs of cardiac enlargement on imaging studies, but they still do not exhibit clinical signs of heart failure, although a degree of exercise intolerance can be observed in some dogs. The cardiac enlargement is typically due to volume overload caused by the regurgitation of blood through the mitral valve.

Stage B2 criteria includes a heart murmur intensity equal to, or more than, three out of six, echocardiographic evidence of left atrial enlargement (left atrium to aorta ratio [LA:Ao] in early diastole equal to or more than 1.6), enlarged left ventricular diameter in diastole normalised for bodyweight (LVIDDN; equal to or greater than 1.7) and breed-adjusted radiographic vertebral heart score (VHS; greater than 10.5). However, the LA:Ao ratio can often be misleading, since it is largely affected by the aortic diameter, which can substantially vary among different breeds and also different individuals.

Furthermore, the authors have noted a large inter-operator variability that can significantly affect the correct estimation of the LA:Ao ratio. Therefore, additional left atrial measurements, such as linear measurements normalised for bodyweight, and left atrial area and volume, may be useful.

These calculations help provide a more comprehensive and accurate assessment of left atrial size in dogs with MMVD. In stage B2, the attending clinician may recommend medical interventions to delay the onset of clinical signs and improve cardiac function.

Stage C encompasses dogs that have developed clinical signs of CHF due to MMVD, including exercise intolerance, rapid or laboured breathing and, more rarely, episodes of fainting. Unfortunately, widespread assumption exists that a dog with a murmur that coughs must be in CHF. This concept is dangerously misleading, since the primary cause of cough in these patients is nearly invariably the activation of coughing receptors facilitated by underlying respiratory disease, with the stimulation of cough receptors being further exacerbated by cardiomegaly compressing their airways (Ferasin et al, 2013).

Therefore, these dogs often start coughing some time before the onset of CHF and this can mistakenly prompt diuretic treatment, sometimes at high doses due to the inconsistent clinical response, associated with the inevitable side effects of chronic diuresis (polyuria/polydipsia, chronic dehydration, electrolyte imbalance, potential hypotension and kidney damage). Treatment at this stage involves the use of multiple drugs to manage heart failure and improve the dog’s quality of life. However, diuretic therapy is indicated at this stage once dogs develop CHF. Some dogs may require hospitalisation for more intensive therapy during episodes of acute decompensation.

Stage D is the most advanced stage of MMVD, where dogs exhibit refractory heart failure despite optimal medical management. Dogs in this stage often experience recurrent episodes of decompensation and severe clinical signs that significantly impact their quality of life.

The staging of mitral valve disease in dogs is a valuable tool for veterinarians to assess disease severity and make informed treatment decisions. Early detection and proactive management are key to slowing the progression of this chronic condition and ensuring the well-being of our canine companions.

In summary, staging mitral valve disease in dogs is an essential tool for veterinarians to evaluate disease severity and make informed treatment choices, while ensuring that the selected therapy is indicated and appropriate for the stage of the disease. By comprehending the progression from stage A to D, clinicians can customise their management approaches to each dog’s specific needs, thereby enhancing their quality of life and longevity.

Mitral INsufficiency Echocardiographic staging system

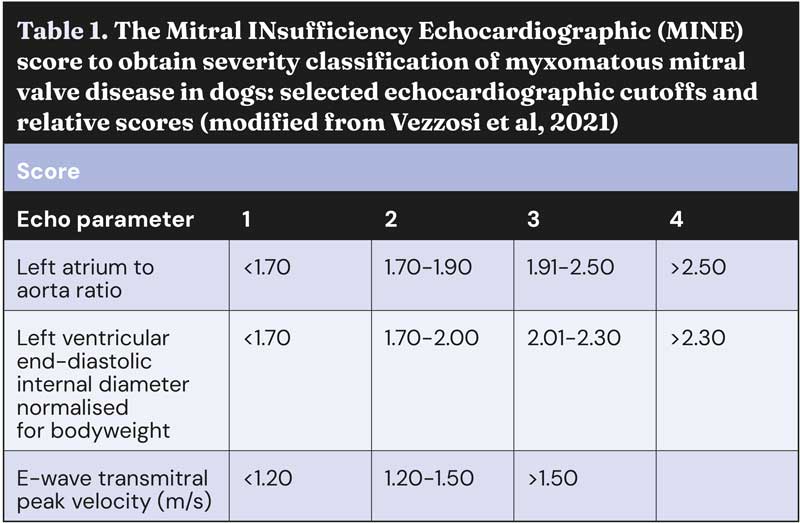

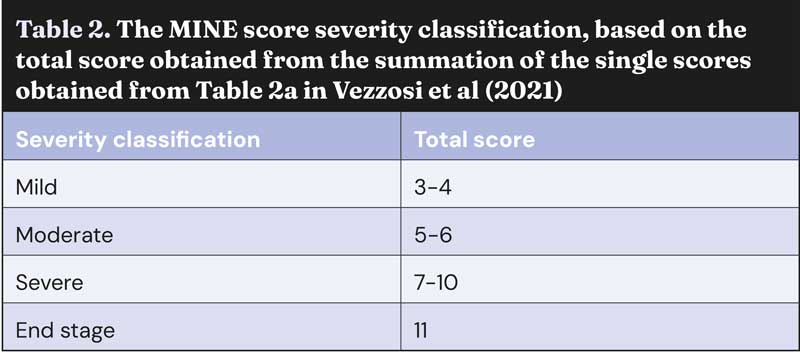

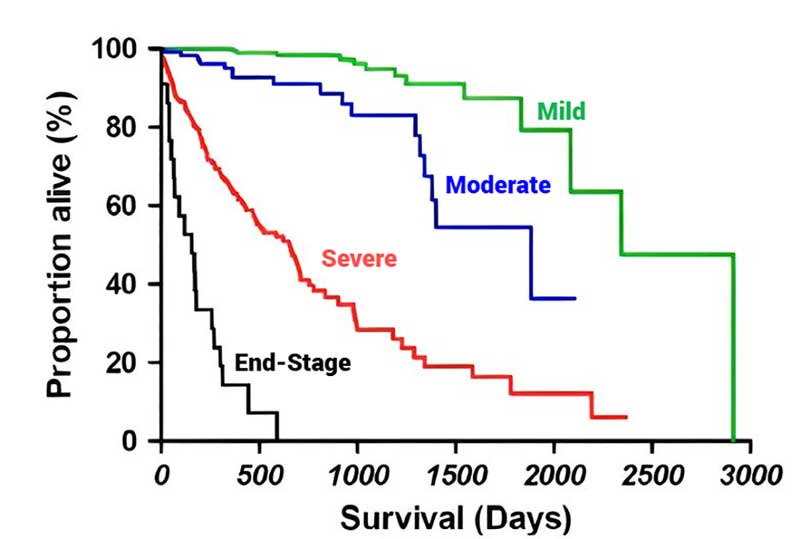

In 2021, a group of Italian cardiologists proposed a different staging system that allows a more accurate and user-friendly echocardiographic classification of severity of MMVD. The Mitral INsufficiency Echocardiographic (MINE) scoring system has been proven clinically effective, as it correlates with survival outcomes.

By offering an objective method for assessing MMVD severity, the MINE score helps clinicians make informed treatment decisions and better manage the disease. In particular, dogs in ACVIM stage B2 that are classified as “severe” according to the MINE score could represent a subset of individuals representative of a proposal for the definition of an “advanced” B2 stage, currently not contemplated by the ACVIM consensus statement.

The MINE score was updated and simplified at the European Congress of Veterinary Internal Medicine Annual Congress 2023; since then, it no longer includes the evaluation of left ventricular fractional shortening, leaving only three echocardiographic variables, namely LA:Ao, LVIDDN, and the E-wave transmitral peak velocity (E-vel). Guidelines for the correct calculation and interpretation of the MINE score are reported in Tables 1 and 2, and Figure 2.

New trends in the management of MMVD

The most recent ACVIM consensus statement offers important recommendations for the correct management of dogs with MMVD, although it is important to acknowledge the fact that affected dogs may present a variable degree of severity, even among individuals at the same stage of their disease.

Furthermore, a plethora of novel information has been recently released, making some of the ACVIM guidelines (published in 2019) slightly obsolete.

Medical management

Stage A and B1

Most cardiologists would agree that dogs with MMVD stage A and B1 do not require any medical intervention, exercise restriction or dietary modifications, although one study has claimed that a cardiac protection blend of nutrients containing medium-chain triglycerides, fish oil, antioxidants and other key nutrients may slow or prevent MMVD progression (Li et al, 2019). However, a subsequent study showed that feeding a specially formulated diet for one year was not associated with a significantly different rate of change of cardiac size in dogs with subclinical MMVD (Oyama et al, 2023).

Stage B2

Pimobendan

The EPIC study has shown that early administration of pimobendan to dogs with preclinical MMVD (with cardiac remodelling) can significantly delay the onset of CHF and improve survival rates.

By enhancing cardiac contractility and promoting vasodilation, pimobendan helps manage the disease before clinical signs appear, thereby improving the dog’s quality of life and extending its lifespan. Therefore, early intervention with pimobendan is a proactive approach to managing dogs in stage B2, offering a better prognosis and delaying the progression of the disease (Boswood et al, 2016) .

Angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors

Scientific evidence on the use of angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors (ACE-i) in dogs with stage B2 MMVD is mixed.

A systematic review and meta-analysis by Donati et al (2022) evaluated the efficacy and safety of ACE-i in preclinical MMVD dogs with cardiomegaly. The study concluded that ACEi did not significantly reduce the risk of developing CHF or improve cardiovascular-related and all-cause mortality in these dogs.

Nevertheless, the utility of ACE-i in the management of MMVD in dogs remains a vivid topic of discussion among researchers – especially after the publication of a retrospective study of 144 dogs with cardiac disease (Ward et al, 2021), which found that higher doses of ACE-i were associated with increased survival rates.

Specifically, dogs receiving twice-daily dosing showed better survival outcomes compared to those on less frequent dosing schedules. The study concluded that optimising the dosage and frequency of ACE inhibitors could enhance their cardioprotective benefits in dogs with cardiac disease.

Spironolactone

To the best of the authors’ knowledge, at this time (with the exception of a pilot study published by Hezzell et al, 2017), no available controlled studies have assessed the clinical utility of spironolactone in the management of asymptomatic dogs with MMVD. However, the DELAY study evaluated the effects of combined spironolactone and benazepril on delaying the onset of clinical signs in dogs with preclinical MMVD (Borgarelli et al, 2020).

This study found that while this combination therapy did not significantly delay the onset of heart failure, it did show beneficial effects on cardiac remodelling and reduced levels of circulating cardiac biomarkers. These findings suggest that this treatment may still have clinical relevance, even if it does not extend the asymptomatic period as hoped.

Another study investigated the effects of different doses of combined spironolactone and benazepril on the renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system (RAAS) in healthy beagle dogs, and found that higher doses led to significant changes in RAAS biomarkers, including a decrease in angiotensin II and an increase in the angiotensin (1-7) which, unlike angiotensin II, promotes beneficial effects, such as vasodilation, anti-inflammatory and antioxidant properties, offering protective benefits to the heart and kidneys.

These results suggest that combined spironolactone and benazepril can modulate the RAAS in a dose-dependent manner, which may have implications for treating heart disease in dogs; although, prospective studies in dogs affected by MMVD would be necessary to confirm the utility of this alternative medical intervention (Manson et al, 2025).

Stage C

Treatment strategies for dogs with stage C MMVD are mainly aimed at controlling clinical signs of CHF and enhancing the dog’s quality of life. Key components of the treatment plan include the following.

Diuretics

Oral loop diuretics, such as furosemide or torasemide, effectively reduce pulmonary oedema, alleviating tachypnoea and dyspnoea. However, given the several potential side effects, the dose of diuretics should be the minimal daily dose that can control signs of congestion.

Simple monitoring the sleeping respiratory rate (SRR) at home by the dog’s owners represents an excellent strategy to achieve this result, aiming at maintaining the SRR less than 30 breaths per minute. Free apps for smartphones are also available to help the dog’s owners perform this task in the most effortless manner.

Pimobendan

Administration of pimobendan should have started in the preceding stage (B2) and should be continued even in the symptomatic phase (stage C).

Indeed, in addition to diuretics, pimobendan prolongs time to sudden death, euthanasia for cardiac reasons, or treatment failure in dogs with CHF caused by MMVD.

Spironolactone

As a potassium-sparing diuretic and mineralocorticoid receptor blocker, spironolactone counteracts potassium loss induced by loop diuretics and provides additional blockade of the RAAS, which can be beneficial in reducing the progression of the disease.

ACE-i

ACE-i, including enalapril, benazepril, ramipril and imidapril, have been shown to improve clinical signs and increase survival rates in dogs with CHF.

However, even in the symptomatic phase of MMVD, a degree of controversy on the utility of ACE-i still exists. Indeed, one study showed that the addition of an ACE-i to pimobendan and furosemide did not have any beneficial effect on survival time in dogs with CHF secondary to MMVD (Wess et al, 2020). This lack of beneficial effect could be explained by the so called “aldosterone breakthrough” phenomenon, which refers to refers to an unexpected increase in aldosterone levels despite the chronic use of ACE-i.

The exact mechanism behind aldosterone breakthrough is not fully understood, but it is thought to involve the activation of alternative pathways in the RAAS.

A strategy to overcome the aldosterone breakthrough is based on the combined use of spironolactone, which blocks aldosterone receptors and help manage the increased aldosterone levels, as demonstrated by the BESST study that showed that combination of spironolactone and benazepril is superior to benazepril alone, when used with furosemide for the management of mild, moderate or severe CHF caused by MMVD in dogs (Coffman et al, 2021).

Non-pharmacological interventions

Cardiac diets, regular monitoring and lifestyle modifications, such as reducing stress and avoiding strenuous activities, should also be considered in the management of symptomatic dogs with MMVD.

By implementing all these strategies, veterinarians aim to manage symptoms, slow disease progression, and improve the dog’s quality of life.

Stage D

When, after a period of stable CHF, clinical signs of congestion reoccur and become refractory to initial medications, clinicians should consider dose escalation of diuretics until a satisfactory control of the breathing rate and effort is achieved.

A recent study suggests that, before considering euthanasia due to unsatisfactory response to oral diuretics, subcutaneous administration of furosemide should be considered, since it appears to be an efficacious and feasible therapeutic option for providing control of the signs of cardiac congestion in dogs with unsatisfactory response to oral diuresis (Lombardo et al, 2025).

Some clinicians also advocate using higher daily doses of pimobendan by adding a third daily administration (off-label use); although, no scientific evidence exists to support this intervention.

Another controversial recommendation mentioned in the ACVIM guidelines is the use of sildenafil when MMVD is complicated by severe post-capillary pulmonary hypertension. However, in people, this off-label usage of sildenafil intervention appears to be associated with worse clinical outcomes, likely because of the increased flow to an already overloaded left atrium, and should be avoided (Bermejo et al, 2017). Therefore, this intervention must be considered with caution.

Adjunctive treatments, such as the use of anti-arrhythmics, should be based on the individual patient’s considerations.

Future perspectives

Two new therapeutic classes – SGLT-2 inhibitors and GLP-1 receptor agonists – have shown remarkable results in recent cardiovascular outcome studies in human patients with and without type 2 diabetes.

Beyond glucose control, these drug classes address subclinical chronic inflammation, oxidative stress and metabolic dysfunction – common factors linking cardiac, renal and metabolic diseases.

Surgical management

Surgical mitral valve repair

This therapeutic option is only available in a limited number of specialist centres worldwide. This surgery requires cardiopulmonary bypass to perform a left atriotomy, directly visualise the mitral valve apparatus, perform mitral annuloplasty and replace the chordae tendineae, with the goal of restoring leaflet coaptation and reducing or eliminating mitral regurgitation.

This complex procedure necessitates a highly trained and experienced team, specialised equipment, and state-of-the-art facilities. While the outcomes of mitral valve repair can justify its use in managing MMVD, financial constraints and the limited availability of specialist centres may sometimes pose challenges.

Edge to edge mitral valve repair (V-clamp)

This procedure combines thoracotomy and a catheter-based procedure (hybrid technique), avoiding the need for open heart surgery and cardiac bypass.

A delivery needle in inserted into the beating heart through the left ventricular apex, and a small device is placed to staple the valve leaflets together, enabling the valve to function normally while reducing the mitral regurgitation. The procedure is guided by 3D transoesophageal ultrasound and fluoroscopy.

A study involving 50 client-owned dogs demonstrated a high procedural feasibility rate of 96%, with no procedural deaths. This procedure is associated with significant reduction of mitral regurgitation, indicating promising short-term efficacy.

However, operator experience and careful case selection are extremely important for the success of this technique, and long-term follow up is needed to confirm these results (Potter et al, 2024).

- Use of some of the drugs in this article is under the veterinary medicine cascade.

- Appeared in Vet Times (2025), Volume 55, Issue 13, Pages 6-10

References

- Bermejo J, Yotti R, García-Orta R et al (2018). Sildenafil for improving outcomes in patients with corrected valvular heart disease and persistent pulmonary hypertension: a multicenter, double-blind, randomized clinical trial, Eur Heart J 39(15): 1,255-1,264.

- Borgarelli M, Ferasin L, Lamb K et al (2020). DELay of Appearance of sYmptoms of Canine Degenerative Mitral Valve Disease Treated with Spironolactone and Benazepril: the DELAY Study, J Vet Cardiol 27: 34-53.

- Boswood A, Häggström J, Gordon SG et al (2016). Effect of pimobendan in dogs with preclinical myxomatous mitral valve disease and cardiomegaly: the EPIC study-a randomized clinical trial, J Vet Intern Med 30(6): 1,765-1,779.

- Coffman M, Guillot E, Blondel T et al (2021). Clinical efficacy of a benazepril and spironolactone combination in dogs with congestive heart failure due to myxomatous mitral valve disease: the BEnazepril Spironolactone STudy (BESST), J Vet Intern Med 35(4): 1,673-1,687.

- Donati P, Tarducci A, Zanatta R et al (2022). Angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors in preclinical myxomatous mitral valve disease in dogs: systematic review and meta-analysis, J Small Anim Pract 63(5): 362-371.

- Ferasin L, Crews L, Biller DS et al (2013). Risk factors for coughing in dogs with naturally acquired myxomatous mitral valve disease, J Vet Intern Med 27(2): 286-292.

- Hezzell MJ, Boswood A, López-Alvarez J et al (2017). Treatment of dogs with compensated myxomatous mitral valve disease with spironolactone-a pilot study, J Vet Cardiol 19(4): 325-338.

- Keene BW, Atkins CE, Bonagura JD et al (2019). ACVIM consensus guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of myxomatous mitral valve disease in dogs, J Vet Intern Med 33(3): 1,127-1,140.

- Li Q, Heaney A, Langenfeld-McCoy N et al (2019). Dietary intervention reduces left atrial enlargement in dogs with early preclinical myxomatous mitral valve disease: a blinded randomized controlled study in 36 dogs, BMC Vet Res 15(1): 425.

- Ljungvall I, Rishniw M, Porciello F et al (2014). Murmur intensity in small-breed dogs with myxomatous mitral valve disease reflects disease severity, J Small Anim Pract 55(11): 545-550.

- Lombardo SF, Ferasin H and Ferasin L (2025). Subcutaneous furosemide therapy for chronic management of refractory congestive heart failure in dogs and cats, Animals 15(3): 358.

- Manson E, Ward JL, Merodio M et al (2025). Dose-exposure-response of CARDALIS (benazepril /spironolactone) on the classical and alternative arms of the renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system in healthy dogs, J Vet Intern Med 39(1): e17255.

- Oyama MA, Scansen BA, Boswood A et al (2023). Effect of a specially formulated diet on progression of heart enlargement in dogs with subclinical degenerative mitral valve disease, J Vet Intern Med 37(4): 1,323-1,330.

- Potter BM, Orton EC, Scansen BA et al (2024). Clinical feasibility study of transcatheter edge-to-edge mitral valve repair in dogs with the canine V-Clamp device, Front Vet Sci 11: 1448828.

- Vezzosi T, Grosso G, Tognetti R et al (2021). The Mitral INsufficiency Echocardiographic score: a severity classification of myxomatous mitral valve disease in dogs, J Vet Intern Med 35(3): 1,238-1,244.

- Ward JL, Chou Y-Y, Yuan L et al (2021). Retrospective evaluation of a dose-dependent effect of angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors on long-term outcome in dogs with cardiac disease, J Vet Intern Med 35(5): 2,102-2,111

- Wess G, Kresken JG, Wendt R et al (2020). Efficacy of adding ramipril (VAsotop) to the combination of furosemide (Lasix) and pimobendan (VEtmedin) in dogs with mitral valve degeneration: the VALVE trial, J Vet Intern Med 34(6): 2,232-2,241.