4 Nov 2022

Dilated cardiomyopathy in dogs

Pippi Gould and Emily Dutton outline potential aetiology, presentation and treatment of this heart-related disease in certain canine breeds.

Dilated cardiomyopathy is a common cause of morbidity and mortality in the Irish wolfhound. Image © Kamila / Adobe Stock

Dilated cardiomyopathy (DCM) is the second-most common acquired cardiac disease in dogs. A strong genetic basis may exist with marked familial transmission in certain dog breeds. However, more recently, reports of “nutritional DCM” have occurred.

This article outlines the latest findings in possible causes, diagnosis and treatment of DCM.

Dilated cardiomyopathy (DCM) is the second-most common acquired cardiac disease in dogs, with large breeds, such as the great Dane (prevalence 35.6%), Newfoundland (10%), Irish wolfhound (24.2%), deerhound (21.6%) and the Dobermann (58%), being overrepresented1-5.

DCM is an idiopathic myocardial disease characterised by ventricular enlargement and impaired systolic function; however, some cases also present with electrocardiographic abnormalities.

DCM is commonly associated with a genetic predisposition in certain breeds. However, several systemic diseases exist that can lead to poor systolic function and ventricular dilation, mimicking the DCM phenotype, which need to be ruled out before the diagnosis of DCM is made. These include volume overload, hypothyroidism, myocarditis or tachycardia-induced cardiomyopathy6,7.

With regards to hypothyroidism, one study in the Dobermann reported no difference in echocardiographic parameters, and the number of ventricular premature complexes between healthy and hypothyroid dogs. However, DCM-affected Dobermanns had a 2.26-fold increased risk of also being affected by hypothyroidism8. Therefore, some confusion exists about the role of this endocrine disease causing DCM.

Dietary factors have also been documented in some breeds, with low taurine and L-carnitine plasma concentrations being associated with a DCM phenotype in the English cocker spaniel and golden retriever9-11. Also, the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has announced it was investigating a link between increased reports of nutritional cardiomyopathies and certain commercial grain-free diets containing peas, lentils, other legume seeds, or potatoes as main ingredients12.

Identification and treatment of these underlying conditions can result in improvement in the echocardiographic changes, but may not be curative.

Grain-free diets and nutritional cardiomyopathy

An increase in reports of nutritional cardiomyopathy with a DCM phenotype has occurred. This has led to releases by regulatory agencies and opinion-based articles proposing a link to grain-free diets.

Several retrospective and prospective studies have been performed since10,13. Some studies suggest it is not only taurine deficiency contributing to this phenomenon, but the presence of other ingredients that may be reducing the bioavailability of certain nutrients, or possible inadvertent inclusion of toxic ingredients such as peas14-16. However, further investigation is required into the association between a dilated, poorly contractile heart, and both grain-free and grain-containing diets.

In the meantime, the FDA recommends that cases with a suspected nutritional cardiomyopathy should have circulating taurine levels measured and the patient is started on a standard ingredient commercial diet, regardless of the results.

Oral taurine supplementation is critical in cases where taurine deficiency is documented. Taurine-deficient golden retrievers and American cocker spaniels showed a significant improvement in their echocardiographic parameters following taurine supplementation9,10.

The benefit of oral taurine supplementation in patients with plasma taurine concentrations within reference range is unknown. Oral taurine supplementation may have a positive effect due to its antioxidant and positive ionotropic effects.

Genetics

Primary DCM remains an idiopathic disease, but growing evidence exists demonstrating that, as in humans, canine DCM has a strong genetic basis with marked familial transmission. However, as in people, the exact molecular biology mechanisms leading to its phenotypic expression are still unknown.

It has been hypothesised each breed may have its own genetic mutation leading to DCM. It is possible that various dog breeds share the same or similar causative genetic disorders. Previous studies in Irish wolfhounds indicate that genotypes at multiple loci interact to influence disease development17,18.

At present, commercial DNA tests are available in the US for the Dobermann, testing for variants in the PDK4 and TTN gene. However, a later study in European-derived Dobermanns showed no evidence in the involvement of the PDK4 gene mutation and the development of DCM, which further illustrates the poorly understood genetic interactions and variability in this disease19. As such, DNA tests are not recommended in Europe for selection of candidates for breeding.

Instead, current recommendations for screening Dobermanns for DCM include echocardiography and 24-hour ambulatory ECG (Holter) monitors from three years of age for those dogs involved in breeding programmes. Given the propensity of males to pass on the disease to a greater number than females, emphasis should be placed on screening males annually, and females and non-breeding dogs every two years if financial limitations are present20.

The GENDEER Study

The authors, along with professors Jo Dukes-McEwan, Lucy Davison and Ottmar Distl, are carrying out research assessing whether genetic basis to DCM exists in the deerhound. The study is called “GENetic associations with dilated cardiomyopathy in DEERhounds”; the GENDEER Study.

Discovering a genetic basis to primary DCM in the deerhound may help in the discovery of a DNA test for DCM in this breed. A genetic test or panel of tests could aid diagnosis of DCM in individual dogs.

The team is looking for help collating samples from DCM-affected cases, and would request any surplus blood from deerhounds to be sent to us in ethylenediamine tetraacetic acid for future DNA analysis (more information and a consent form can be found online).

The team is very grateful to PetSavers and the Veterinary Cardiovascular Society for their generous funding of this study. For any questions regarding the GENDEER Study, or if you have a case that may be suitable, email [email protected]

Clinical presentation

Overt DCM is typically an adult-onset disease with a mean age of 7.2 years21. However, age of presentation can vary with breed, and some exceptions developing juvenile forms of it exist22. Examples include the Portuguese water dog, which can develop a juvenile form, with affected dogs dying within the first seven months of life23. A group of standard schnauzers also had a juvenile presentation on average at 1.6 years old with a mean survival time of 22 days once congestive heart failure developed24.

After pedigree analysis, a suggestive familial predisposition was present. In most breeds, the preclinical stage, also referred to as “occult” DCM, can last years without clinical signs. Although soft systolic murmurs, due to stretch of the mitral valve annulus, or arrhythmias may be detected on clinical exam, they are not always present.

However, diagnosing and treating preclinical DCM early using echocardiography and ECG can significantly delay the onset of the clinical stage of disease, and subsequently, extend survival times25,26.

Clinical DCM has several clinical signs, such as exercise intolerance, tachypnoea or collapse. Clinical exam findings can be variable, but include heart murmurs, gallop sounds, decreased heart sound intensity, jugular distension, pulse deficits, ascites, hypothermia, pulmonary crackles or arrhythmias, which may result in sudden death. Once clinical signs develop, median survival times are around four months27.

Diagnosis

Echocardiography is required for the diagnosis of DCM to identify the associated myocardial dysfunction and ventricular dilation, while excluding other acquired and congenital cardiac diseases.

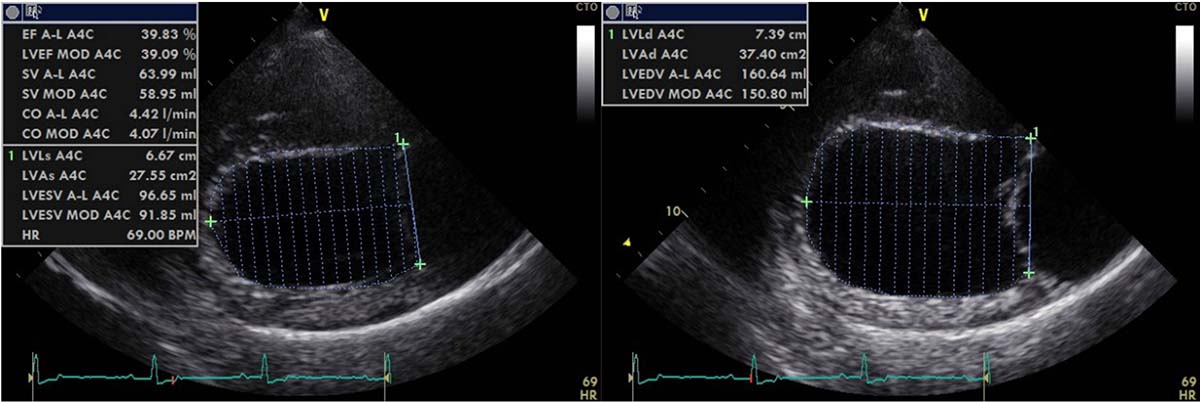

Measuring left ventricular volumes (Figure 1) using Simpson’s method of discs has been shown to be important for early detection of preclinical DCM in Dobermanns and superior to M-mode for detecting early echocardiographic changes28. This has also been shown in deerhounds4.

In fact, one longitudinal study examined the ability of each echo variable to help diagnose DCM in deerhounds, with a view to establishing a cut-off value to help differentiate a DCM group from a normal/equivocal group of deerhounds.

E-point–to–septal–separation was shown to be a reliable variable of systolic function to differentiate DCM-affected from DCM-free deerhounds. Cut-off values of more than 6.5mm in the Dobermann and more than 9.8mm in the deerhound have been suggested to help diagnose DCM; although, the latter needs to be validated in deerhounds4,29. This also highlights the importance of using breed-specific echocardiographic reference intervals when available, due to the large variation in heart size and shape between various breeds.

It has been shown in many studies that the sighthounds have larger volume hearts when scaled to bodyweight compared to non-sighthound breeds4,24,30-34. Therefore, the authors advise caution not to over-diagnose a dilated left ventricle when assessing heart size in sighthounds (including when allometrically scaling left ventricular diameter to bodyweight)32.

Vertebral heart score (VHS), an indicator of cardiomegaly, and vertebral left atrial size (VLAS), are two objective radiographic cardiac measurements that have been described in dogs, with specific reference ranges available in some breeds.

Where echocardiography may not be available, use of a physical exam, radiography and biomarkers combined has been shown to be a reasonable indicator of preclinical and clinical DCM35.

However, increased values in these measurements are not exclusive to DCM and could be secondary to other cardiac diseases. An example is myxomatous mitral valve disease. This highlights the importance of using echocardiography to help diagnose DCM.

When combining physical exam findings with a high VLAS or VHS, this can be a useful indicator of clinically important heart disease in the emergency setting36.

The biomarkers N-terminal pro B-type natriuretic peptide and high-sensitivity cardiac troponin I have also been shown to be useful for screening Dobermanns for the dilated form of DCM, but less so for the identification of the “arrhythmic” form of Dobermann DCM37.

It must be emphasised that the cardiac biomarker results should not replace echocardiography and Holter, but they may help the triaging of Dobermanns that benefit from full screening.

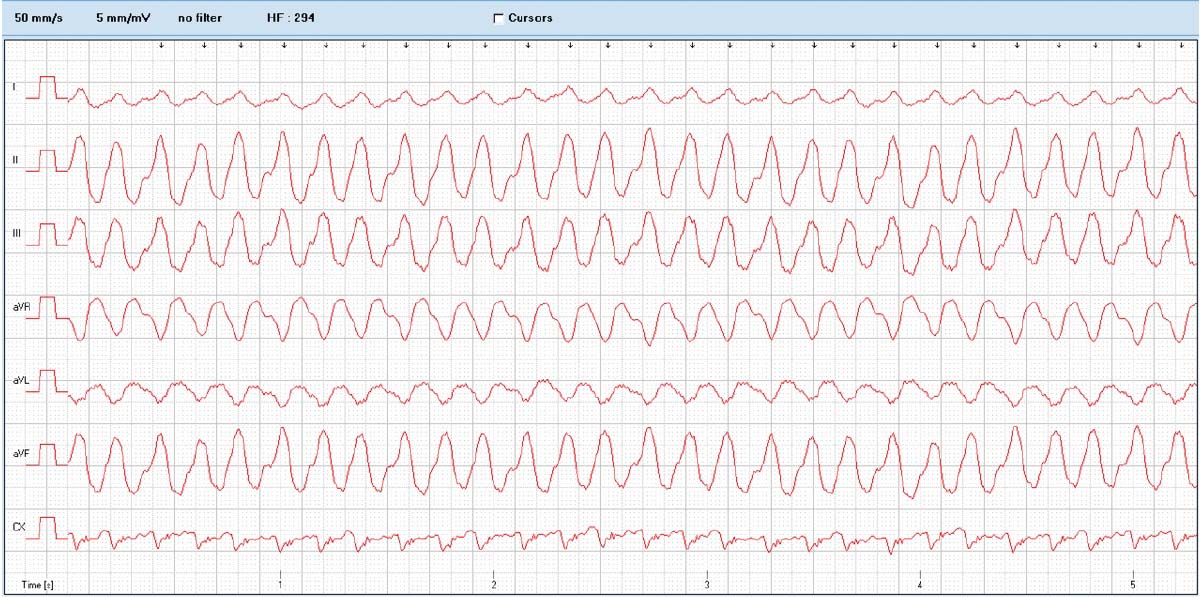

Dogs with DCM can present with echocardiographic evidence of systolic dysfunction and ventricular dilation, or the arrhythmic form, which may lead to sudden death. Due to the high prevalence of preclinical DCM cases with ventricular arrhythmias (VAs), ECG is recommended to identify these arrhythmias4 (Figure 2).

Atrial fibrillation (AF) is also frequently present and, in the Dobermann, has been shown to be a poor prognostic indicator38. Lone AF can also occur in the Irish wolfhound and may be a potential precursor to DCM.

One study demonstrated 50% of Irish wolfhounds with lone AF went on to develop DCM and the incidence increased with age. However, not all Irish wolfhounds with AF go on to develop DCM25,39.

Continuous ambulatory ECG (Holter) monitors are particularly useful in cases where arrhythmias are present. Their uses include determining the number and complexity of VAs, whether anti-arrhythmic treatment is necessary, and to help exclude tachycardia-induced cardiomyopathy.

Treatment

Treatment of DCM varies with the stage of presentation and whether rhythm abnormalities are present.

Pimobendan, an inodilator, is recommended during the preclinical and clinical stages, prescribed at a dose of 0.2mg/kg to 0.3mg/kg by mouth twice daily. In the emergency setting, an IV preparation of pimobendan is also available for single dose at 0.15mg/kg. In the Dobermann pincher, pimobendan delayed the onset of heart failure or sudden death from 441 to 718 days when commenced during the preclinical stage26.

When pimobendan is not available, dobutamine (also a positive inotrope) can be administered as a CRI at 2mcg/kg/min to 15mcg/kg/min. Dobutamine can, however, be pro-arrhythmic, so careful monitoring using ECG and blood pressure measurements is required.

ACE inhibitors have been shown to reduce the mortality rate in humans with impaired systolic dysfunction40. A retrospective study in Dobermanns showed benazepril hydrochloride prescribed at a dose of 0.5mg/kg by mouth once daily delayed the onset of congestive heart failure (CHF) or death by three months when compared to a control group41.

The use of benazepril during the preclinical phase of DCM is, therefore, advocated by some cardiologists. However, prospective, randomised placebo-controlled studies in non-Dobermann dog breeds are warranted to test this theory.

ACE inhibitors should also only be prescribed in normotensive patients. Loop diuretics are also recommended once CHF develops, usually titrated to effect, but with a starting dose of up to 2mg/kg IV of furosemide in the acute presentation of CHF, along with oxygen therapy.

A prospective study of spironolactone in 18 Dobermanns with CHF showed no significant difference in survival time between the spironolactone group and the placebo group. However, interestingly, Dobermanns receiving spironolactone had a reduced occurrence of atrial fibrillation42. Spironolactone is an aldosterone antagonist that reduces myocardial fibrosis, as well as being a weak potassium-sparing diuretic. Spironolactone is not currently licensed for use in DCM.

In the event of ventricular tachycardia, a slow bolus of lidocaine IV is recommended at 2mg/kg in normokalaemic patients. This bolus can be repeated every 10 minutes and up to a total dose of 8mg/kg to attempt to convert the rhythm to sinus rhythm.

If successful conversion to sinus rhythm occurs, then a lidocaine CRI of 40mcg/min/kg to 80mcg/min/kg should be immediately commenced. This may be followed by oral mexiletine, a class IB anti-arrhythmic medication, after weaning the patient off the lidocaine CRI.

Mexiletine is a sodium channel blocker and can be prescribed for the chronic management of ventricular arrhythmias. In dogs with complex, uncontrolled VAs and at high risk of sudden death, such as the boxer or the bulldog with arrhythmogenic right ventricular cardiomyopathy, the addition of sotalol (a combination class II/III anti-arrhythmic medication) may be recommended by a cardiologist.

Note that sotalol has negative inotropic effects; therefore, it should be prescribed with caution in dogs with DCM.

None of these drugs are licensed for use in dogs and all anti-arrhythmic medications have the potential to be pro-arrhythmic.

Owners must also be made aware little published evidence exists to suggest that anti-arrhythmic treatment reduces the likelihood of sudden death or prolongs life expectancy. The goal of treatment is to alleviate any clinical signs, such as collapse (due to haemodynamic compromise), and to help prevent sudden death.

Advice from a specialist is recommended when starting antiarrhythmic medications in cases with DCM. AF (Figure 3) can also occur when atrial stretch occurs secondary to DCM. Conversion to sinus rhythm is challenging in dogs with DCM; therefore, the therapeutic goal is maintaining a normal ventricular rate to optimise cardiac output.

![Figure 3. Above is an example of atrial fibrillation [AF] (50mm/sec; 5mm/mV). Note the irregularly irregular, supraventricular rhythm with a lack of P waves at more than 180bpm, consistent with AF.](https://www.vettimes.co.uk/app/uploads/2022/10/VT5244-Gould-Dutton-Figure3.jpg)

However, one study suggested that the combination of both diltiazem and digoxin resulted in a superior reduction in heart rate when compared to either drug alone43.

The dose of digoxin need only be high enough to increase vagal tone and reduce heart rate. Owners should be warned of the side effects of digoxin therapy before treatment is initiated. Close monitoring of circulating renal parameters, electrolyte concentrations and digoxin therapeutic levels is vital.

Conclusions

The ability to diagnose and treat DCM in dogs is an active area of ongoing research.

In particular, improving quality of life, as well as increasing longevity, is very important.

Early detection of DCM and effective, targeted monitoring of the condition is important to help optimise the treatment plan long term.