15 Jul 2025

ESCCAP maps: new tool in Europe’s rapidly evolving parasite landscape

Ian Wright BVMS, BSc, MSc, MRCVS explains the importance of movement tracking and future change prediction, and what is available to assist this.

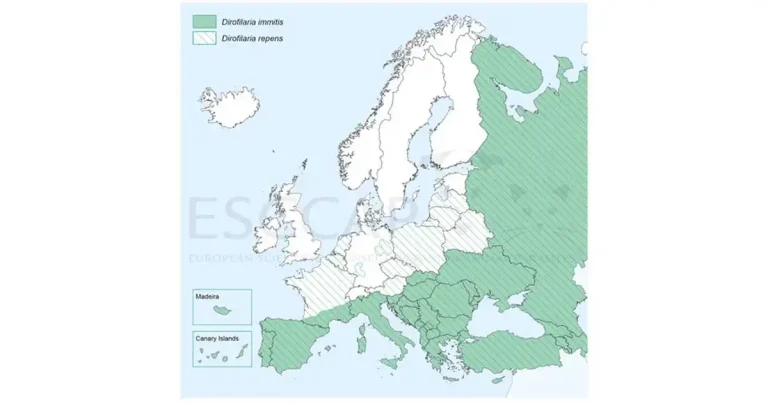

Figure 1. Distribution of Dirofilaria immtis and Dirofilaria repens in Europe.

Founded in 2005, the European Scientific Counsel Companion Animal Parasites (ESCCAP) is a not-for-profit organisation made up of parasitology experts, vets and nurses from across Europe.

Its primary aim is to protect the health of pets from parasites, reduce zoonotic risk and preserve the human-animal bond. Its work includes filling knowledge gaps in veterinary parasitology while presenting existing data in an accessible way through guidelines, fact sheets and CPD.

ESCCAP, through its guidelines and other resources, also seeks to give consistent advice on parasite control across Europe, with national associations giving more tailored advice and information to fit regional epidemiological situations and laws.

The role that ESCCAP fills has become even more important in recent years as climate change, alongside increased movement of pets and humans, has led to wider parasite distributions.

Importance of maps

Mapping of parasite distributions plays a vital role in informing current parasite risk and potential future trends. Parasite maps fall broadly into three categories.

Prevalence/distribution maps. These show where parasites are currently known to be endemic and, in some cases, their reported prevalence in different regions.

Infection reporting maps. These are not prevalence maps and do not indicate whether a parasite is endemic; rather, they show the proportion of animals that tested positive for a parasite in a country or region.

Modelling/predictive maps. These use factors such as climate, hosts and habitat trends to predict how the distributions of parasites and their vectors will change over time.

ESCCAP’s maps, showing where parasites have been confirmed to be endemic, have proven invaluable in helping veterinary professionals assess whether parasites are likely to be encountered in their country. They also help to inform vets which parasites pets might have encountered while living or travelling abroad (for example, ESCCAP’s heartworm map; Figure 1). They do not, however, show the number of pets being diagnosed with parasitic infections, those exposed to infection and those that have been diagnosed with non-endemic infections.

Maps showing test results from labs across Europe help to fill in these gaps, enabling veterinary professionals to see what is being diagnosed in their country. This is useful in risk planning, raising awareness among pet owners and giving an indication of parasites that may become endemic if control measures are not put in place.

The Companion Animal Parasite Council in North America has long had infection reporting maps (confusingly called prevalence maps) available to vets and pet owners, and they have been useful in raising awareness about individual parasite risks and where they may be spreading.

An example of this is heartworm, where relocation of rescue dogs from natural disaster sites such as Hurricane Katrina has led to heartworm being present in parts of the US where it would not be expected (Drake and Parrish, 2019).

The parasite is not endemic in some of these regions, but mapping showing their presence has led veterinary professionals to include heartworm in their differentials for cardiopulmonary disease. It also raises awareness that the parasite may establish as the climate warms, with both vector and parasite being present, enabling it to complete its life cycle. A similar situation is occurring with Leishmania species in northern Europe. Although the sand fly vector is not endemic, large numbers of cases are being seen in the UK, Germany and other northern European countries due to pet relocation (Miro et al, 2021). This makes consideration of Leishmania species as a differential in cats and dogs, with relevant clinical signs essential.

Early diagnosis improves prognostic outcomes, but also helps to prevent non-vectorial transmission routes such as venereal, congenital and blood transfusions. Viable sand fly vectors are also spreading as the climate changes, so knowing where cases are occurring is vital to prevent endemic establishment as the parasite spreads.

Infection reporting maps do not infer endemicity or population prevalence. While infection reporting maps generate useful data for surveillance and planning, they are not prevalence maps. Although they give vital information regarding the presence of infected pets in a country, they tell us nothing about prevalence or endemicity. This is because tested cats and dogs are likely to come from a variety of sources that are not likely to be representative of the population. These include the following.

Clinical cases. Where the parasite is considered as a possible cause for the presenting clinical signs.

Travelled pets. As part of screening for exotic pathogens in both animals showing clinical signs and those that appear healthy on presentation.

Young pets. These are more likely to be imported and travel and therefore more likely to be screened. Younger pets are also more likely to exhibit clinical signs of infection from many parasites such as Angiostrongylus vasorum, Giardia species and Cystoisospora species.

Pets on treatment. These may be tested as part of routine checks for intestinal parasites and, in endemic countries, Leishmania species and heartworm. If these pets are on preventive treatment, it will drive down the proportion of tests that are positive.

For these reasons, parasite infection maps such as those launched by ESCCAP should not be over-interpreted, but used as a means of raising awareness regarding positive cases for both endemic and exotic cases being identified, and changing trends over time.

ESCCAP parasite infection maps

These new parasite maps depict the proportion of pet cats and dogs tested that test positive for a given parasite, using available assays in Europe.

For canines, the maps cover Dirofilaria immitis (heartworm), Giardia, Trichuris whipworm, Toxocara roundworms, hookworms, Dipylidium caninum, Ehrlichia, Anaplasma, Borrelia, Leishmania and Babesia species.

For cats, maps will cover Giardia species, Toxocara roundworms and hookworms. The parasites included will likely change over time, depending on data available across Europe.

As of their launch at the end of May 2025, Idexx is the sole contributor of data, and the plan is to recruit more labs from across Europe to also supply results. Any lab is welcome to contact ESCCAP and get involved in this rapidly evolving project.

As the maps raise awareness of parasites in different regions, the hope is that this will also encourage more testing, which in turn will further strengthen the maps.

The maps can be found at www.esccap.org/parasite-infection-map

Conclusion

Mapping is an exciting and evolving area that is becoming increasingly important, and parasite distributions rapidly change.

Understanding the different types of maps available, however, is key to using them effectively when planning parasite control and considering differentials for clinically affected pets.

ESCCAP will continue to develop its maps as an essential component of its parasite information portfolio.

- Article appeared in Vet Times (2025), Volume 55, Issue 28, Pages 10-12

IAN WRIGHT is a practising vet and co-owner of The Mount Veterinary Practice in Fleetwood, Lancashire. He has a master’s degree in veterinary parasitology and is head of the European Scientific Counsel Companion Animal Parasites (ESCCAP) UK and Ireland, and guidelines director for ESCCAP Europe.

References

- Drake J and Parrish RS (2019). Dog importation and changes in heartworm prevalence in Colorado 2013–2017, Parasites and Vectors 12(1): 207.

- Miró G, Wright I, Michael H, Burton W, Hegarty E, Rodón J, Buch J, Pantchev N and von Samson-Himmelstjerna G (2022). Seropositivity of main vector-borne pathogens in dogs across Europe, Parasites and Vectors 15(1): 189.