1 Nov 2019

Libby Sheridan discusses the changes in metabolic and energy requirements in older pets, and why nutritional assessments should be carried out frequently to ensure diets are optimal.

Image © New Africa / Adobe Stock

It’s a very common conundrum – you are presented with an eight-year-old chocolate Labrador retriever that, on the face of it, looks to be springy and alert.

It is slightly podgy around the waist – no obvious abdominal tuck – and a bit grey around the chops.

Is now the time to discuss changing it to a senior pet food, maybe a low-calorie option? Or are we afraid of the owner’s likely reply: “But he’s not old, he’s like a puppy – especially when it comes to feeding time. We hope there’s years left in him yet.”

It can be difficult to challenge an owner’s perception of his or her pet, but, at the same time, any adjustment to routine – including feeding – is going to need an owner to be fully on board and understanding of the reasons for change.

Many pet food manufacturers, with a life stage range, will delineate in terms of age. Many of us will be familiar with the switch to a senior food between 7 and 10 years of age. Manufacturers recognise that, generally, many pets will be starting to develop ageing changes from about mid-life, and providing a set “rule” aims to help the average owner in knowing when to switch.

However, convincing an owner of the need may be trickier – especially when his or her pet shows no obvious signs of ageing to him or her. Additionally, as veterinary professionals, it can prove challenging in knowing what diet to switch to.

Pet foods marketed for senior pets can vary enormously in their nutritional make-up. The European Pet Food Industry (FEDIAF) sets nutrient guidelines for growth, and for adult dogs and cats; however, no specific guidelines exist for senior pets. This is because requirements within this life stage can vary enormously and much more than within other age ranges (Fascetti and Delaney, 2012).

Different manufacturers will also have different nutritional philosophies – with some choosing to restrict the protein levels in senior food, some restricting fat and others capping phosphorus content.

So, what to do?

In other disciplines, the latest clinical evidence will be sought. However, nutritional strategies for ageing pets is a field where not a lot of published data is available, although research is increasing.

What we do know is that a “one size fits all” approach is not ideal.

The WSAVA recommends every pet has a nutritional assessment carried out at every consult. The optimal diet for any pet should only be recommended after a comprehensive review, which includes the existing diet, the pet itself and the owner’s lifestyle.

This approach of assessing the owner’s perceptions and expectations is important. Without his or her understanding and agreement, it is likely compliance with suggested nutritional changes will falter – particularly in this era of mixed messaging on feeding. Advice online varies greatly, and is often incorrect.

It is vital to ensure recommendations are clearly made and take into consideration:

During the consult, some carefully constructed open questions can help to draw out owner perceptions of his or her pet’s lifestyle. Does he or she accept certain clinical signs as “normal ageing”?

An owner may not proactively mention his or her cat no longer jumps on to the windowsill, or his or her dog now refuses to go through a particular gate en route to the park. However, these signs might indicate the possibility of OA, cognitive decline, or other ageing or pathological processes that could be helped by nutritional intervention.

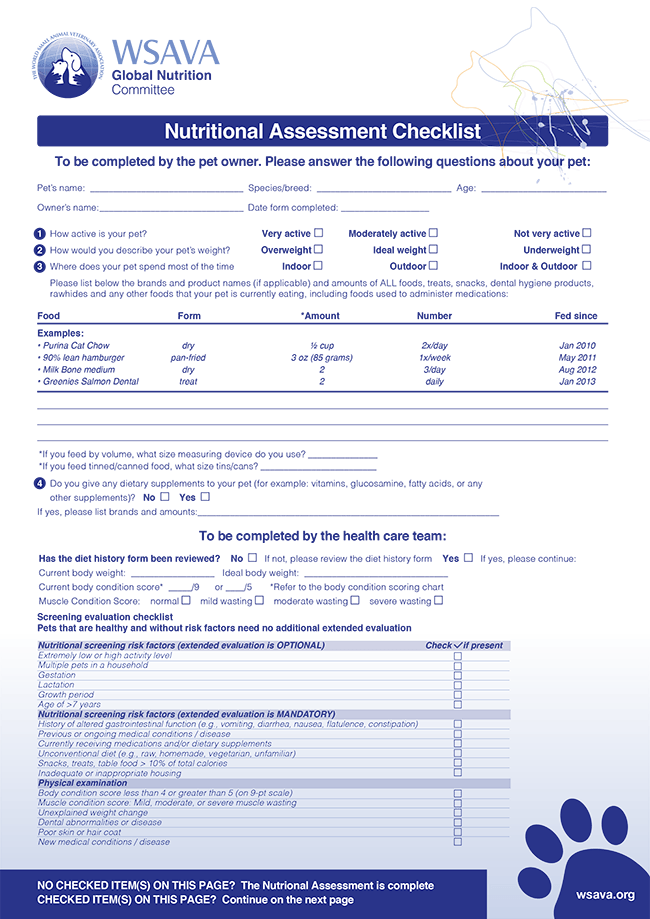

A nutritional assessment should be comprehensive. Using a checklist, such as that provided by the WSAVA, is helpful to ensure as much information as possible is gathered. This checklist could form part of an overall senior check-up and, combined with a thorough history taking, can give deep insights into a pet’s ability to age healthily.

Building a nutritional assessment into a yearly questionnaire – performed with the owner every time the pet comes in for a vaccination, for example – will enhance the owner’s appreciation of the value of nutritional advice and provide an excellent history of the changing needs of the pet.

Given that research has shown an average dog older than nine years of age may have up to eight previously unrecognised problems at play (Davies, 2012) stresses the importance of doing a thorough evaluation and can help to justify this to a reluctant owner.

The nutritional assessment should also screen for risk factors (which includes a pet being older than seven years of age), which then leads to an extended evaluation for patients in which risk factors are subsequently identified. An example of this checklist is shown in Figure 1.

The goal of a regular nutritional assessment is ensuring dietary changes can be instigated as early as possible to help maximise the pet’s lifespan and quality of life (Churchill, 2018). Once a recommendation has been made, it is important to remember this is not set in stone. Regular re-evaluation is crucial.

Ageing itself is not a disease. It can be defined as the progressive physiological and metabolic changes that occur in the body after maturity, which lead to a decrease in organ function (Fahey et al, 2008).

The process is not linear – it varies enormously between individuals. Factors such as gene make-up, breed size, environment and nutrition will all influence the ageing process (Laflamme, 1997).

Physiological and metabolic changes include alterations in energy requirements. Ageing dogs have a decreased metabolic energy requirement (MER) by an average of 25%, but their digestive system retains a good degree of absorptive function (Churchill, 2018; Chandler, 2018).

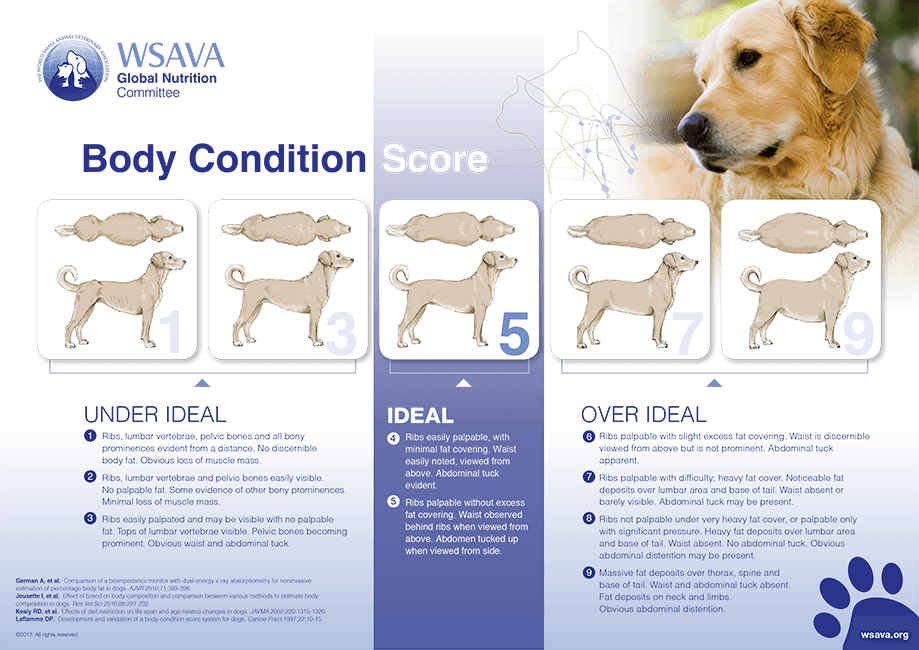

The decreased MER is, in the main, caused by a loss of lean body mass, exacerbated by a decline in exercise. However, loss in muscle mass may be obscured by a gain in fat mass. This is why muscle condition scoring (MCS) should be carried out on every senior pet, at the same time as body condition scoring (BCS). This can pick up changes to lean body mass and allow changes to nutrition or exercise to be made, or, if disease is suspected, investigation to start.

Veterinary professionals will need to make gradual adjustments to an older dog’s energy intake in line with the progressive reduction in MER. This will help decrease the risk of obesity or exacerbation of many age-related conditions (Churchill, 2018).

Maintenance of an appropriate bodyweight and correct energy balance – taking action on any overweight or existing obesity – and preventing weight gain or obesity from developing should be one of the most important aims of any nutritional plan (Churchill, 2018).

Changes in MER in older cats are more contentious. In cats, MER tends to remain quite stable or decreases mildly until 10 to 12 years of age. Thereafter, a progressive decrease in MER of approximately 3% per year, up to the age of 11 years, may be seen (Laflamme, 2005).

Interestingly, after this point, studies have actually found an increase in MER of geriatric cats (Laflamme, 2005). This is suggested to be the result of a less marked decrease in activity levels (Fahey, 2008).

However, some changes are seen in the digestive system, with as many as a third of older cats demonstrating a compromise in their ability to digest fat. Their ability to digest protein also decreases – and together, this overall decrease in digestive ability contributes to a need for an increase in dietary energy needed for older cats (Laflamme, 2005).

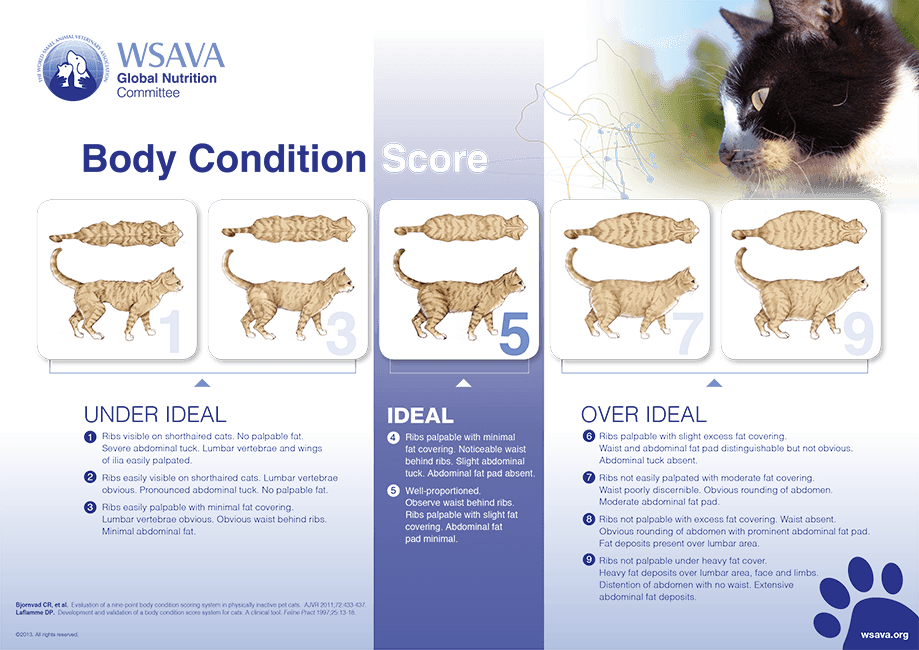

Maintaining body condition is key – with a focus on obesity prevention between 7 and 11 years of age, after which focus should be switched to preventing weight loss. Carrying out an MCS and BCS at every visit will help bodyweight to stay on track. A validated nine-point BCS system for dogs and cats is shown in Figure 2.

Sarcopenia, defined as muscle wastage occurring in the absence of disease, is a notable part of the ageing process (Laflamme, 2018).

Cats lose about a third of lean muscle mass from the age of 10 to 15 years (Laflamme, 2018). This, combined with their decreased ability to digest fat, contributes to the occasional presentation of a thin, elderly cat with a remarkably normal blood profile.

Senior dogs lose approximately 10% lean body mass over the same period, but, at the same time, may see a 10% increase in their fat mass (Laflamme, 2018). This may make it difficult for veterinary professionals to identify muscle deterioration, and an MCS examination is recommended to always be carried out at the same time as a BCS.

The WSAVA provides excellent guidance to MCS on its website. This involves palpation of various muscle sites in the body – including the epaxial muscles, and over the skull, scapulae and hips. Any muscle loss is graded as mild, moderate, or severe.

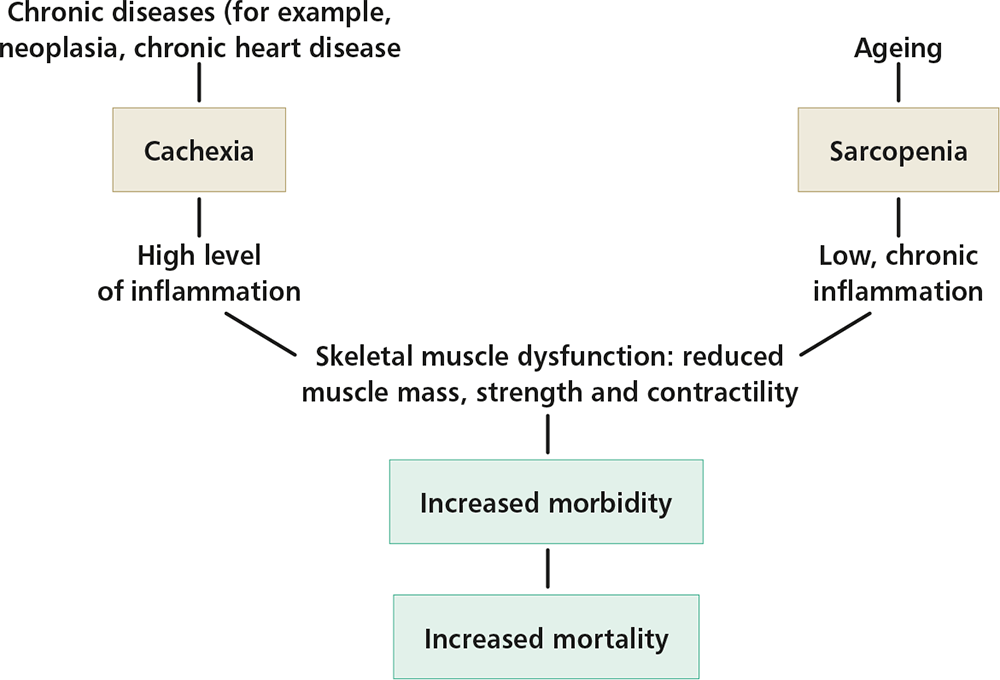

Loss of muscle mass should be differentiated from cachexia – muscle wastage associated with disease. Both require investigation, as both are associated with increased risks for morbidity and mortality (Figure 3).

Sarcopenia is thought to be multifactorial (Laflamme, 2018). More is known about the condition in humans, where it is believed multiple management factors – including physical exercise and, importantly, nutrition – can minimise its incidence and/or severity (Laflamme, 2018).

If dietary protein intake is inadequate, protein will initially be taken from skeletal muscle, which will accelerate muscle wastage. While general guidelines for protein intake have been suggested, some think senior animals may need up to 50% more than this (Churchill, 2018).

A reduction in sarcopenia in dogs and cats has been demonstrated as a result of increasing protein intake (Laflamme, 2018). So far, though, no optimal protein level has been identified and research is ongoing. Some pet foods restrict protein as part of a standard senior formulation, along with phosphorus and fat; however, because of the complexity of senior ageing, a more tailored, individual approach is advised.

As well as changes in digestion, and muscle and fat metabolism, organ function deteriorates as the pet ages, with a loss of compensating ability. Immune and sensory functions also decline (Fascetti and Delaney, 2012). Deterioration in the pet’s ability to smell may affect the pet’s food intake. Cognition – the brain’s ability to think – can also deteriorate, and lead to multiple behavioural signs, including sleep alteration and loss of toilet training.

All of these processes can be identified on a thorough nutritional and senior assessment. Cognition checklists are available to help stage age-related cognitive decline and differentiate from cognitive dysfunction syndrome. Cognition can be supported by nutritional intervention – including the feeding of medium chain triglycerides – providing the brain with an alternative source of energy in the form of ketones, which it can use more easily than glucose as the brain ages (Pan, 2011).

Making a comprehensive nutritional assessment – and ensuring any dietary adjustment is tailored to the individual pet – will help to ensure the ageing process is as healthy as possible. This should be carried out frequently – with the aim of making regular, appropriate adjustments that will enhance quality of life, and help the owner to enjoy the companionship and enjoyment of his or her pet for as long as possible.

Libby Sheridan

Job Title