13 May 2025

Feline hypertension: latest on treatment and prognosis

Sam Taylor BVetMed(Hons), CertSAM, DipECVIM-CA, MANZCVS, FRCVS lays out the up-to-date information on this condition, and discusses how a team approach can lead to more frequent diagnosis and treatment.

Image: olezzo / Adobe Stock

Hypertension in cats has been described for many years, but challenges remain in the diagnosis and treatment of this condition in practice.

Hypertension occurs most commonly secondary to underlying diseases such as CKD and hyperthyroidism, and can result in various clinical signs affecting target organs (such as the brain, heart, kidneys and eyes).

This article aims to discuss what is new in feline hypertension and how we can work as a team to measure systolic blood pressure (SBP) more often, which will undoubtedly lead to more frequent diagnosis and treatment of the condition.

Recent research on hypertension

Hypertension is an area of growing research, with some recent publications providing useful information on the condition:

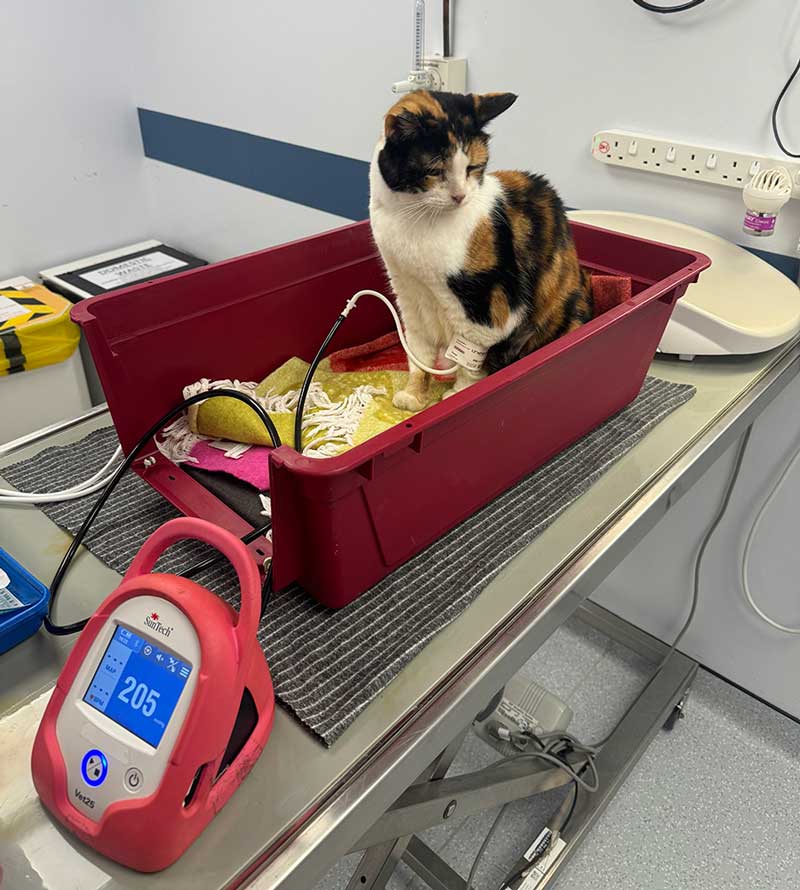

- Knies et al (2024) compared Doppler ultrasonic sphygmomanometry with high-definition oscillometry and found using Doppler (Figure 1) was fast, reliable and gave reliable result. However, the high-definition oscillometric devices were equally easy to use (using the tail in this study), and both techniques took a similar length of time (around four minutes). The measurements from one branded oscillometric device were significantly higher than the measurements from another oscillometric device and the Doppler device in this study.

- Cases and Dye (2024) compared Doppler and oscillometry devices in 50 conscious cats, and found acceptable agreement between the two devices, but the Doppler device had superior repeatable precision. Of the cases with suboptimal agreement, the oscillometric device measured a higher SBP. Therefore, we should always interpret results in individual cats according to repeatability of measurements, comorbidities and the cat’s demeanour. Assessing for target organ damage – particularly retinal examination – can assist interpreting results.

- Flora et al (2025) studied gross and histopathological findings in the hearts of hypertensive older cats, mainly with CKD. Hypertension increases afterload, which can lead to left ventricular hypertrophy, and this study showed hypertensive cats had thicker left ventricular free walls and interventricular septa. However, myocardial fibrosis was common in both hypertensive and non-hypertensive aged cats, suggesting that age-related cardiac pathology, exacerbated by azotaemic CKD, is very common. Undoubtedly, control of hypertension will benefit the heart, but the study findings suggested other factors may also be affecting the heart in this age group.

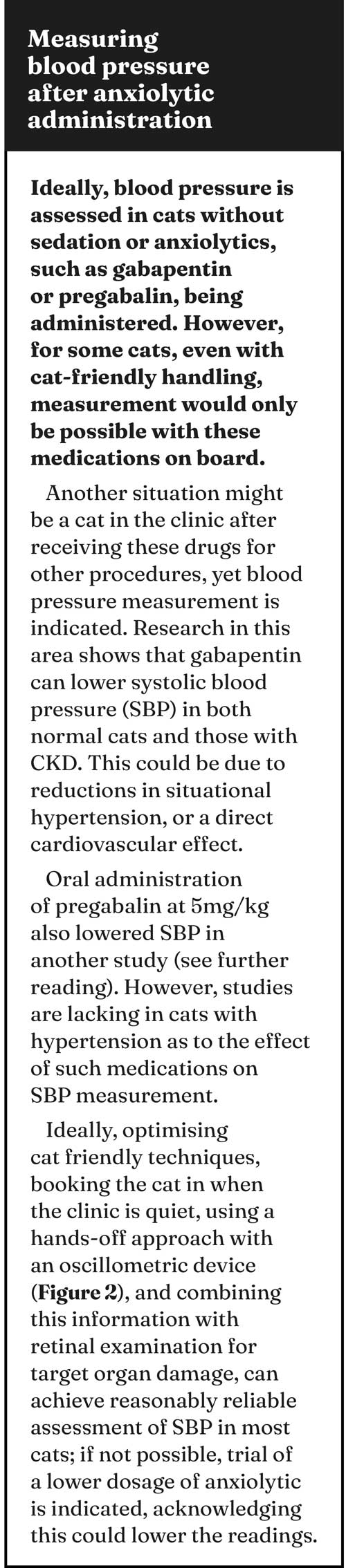

- Stammeleer et al (2024) sought to determine the prevalence of systemic systolic hypertension in a large group of cats with untreated hyperthyroidism, re-assessing blood pressure after radioiodine treatment. Of untreated hyperthyroid (non-azotaemic) cats, 27% were hypertensive based on SBP measurement, but these cats were more likely to be nervous/excited than normotensive cats. Just more than half of these hypertensive, hyperthyroid cats remained hypertensive after radioiodine treatment and 9.5% developed hypertension. The study suggested that around half of hyperthyroid cats considered hypertensive pre-treatment may be normotensive when euthyroid, illustrating the challenges of measuring SBP in hyperthyroid cats and suggesting higher readings could be situational or stress-related and, therefore, resolve. For a good resource with tips on being cat friendly when measuring blood pressure, see the 2022 American Association of Feline Practitioners/International Society of Feline Medicine Cat Friendly Veterinary Interaction Guidelines (bit.ly/3GyDWue).

- Costa Vitor et al (2024) examined SBP in obese and non-obese cats. This was a small study, but the obese and overweight cats had significantly higher SBP than ideal weight cats, which although seemingly obvious, considering the association in humans, has not been well reported in cats. Of note, the obese cats also had higher blood glucose, another reason to promote healthy weight loss if needed.

Options for treatment

We are fortunate to have two options for treatment of hypertension licensed in the UK and other countries: amlodipine and telmisartan.

Amlodipine is generally the treatment of choice when SBP is equal to or more than 180mmHg, or target organ damage is present (www.iris-kidney.com), but telmisartan as an angiotensin receptor blocker may have some theoretical advantages, such as reduction of intraglomerular pressure and reducing proteinuria.

Further investigation is needed to untangle the relationship between prognosis, proteinuria and hypertension in cats. A “one size fits all” does not exist, as dosages may need adjustment, and comorbidities need managing. Monitoring is vital and need not be expensive, as we should take into account body condition and appetite, as well as reassessment of urea and creatinine, and the urine protein-creatinine ratio, for example.

As with all medications prescribed for cats, medication formulation preferences (tablets versus liquid) may also influence choice, and owners should be supported in administering chronic medication – emphasising that it is likely their cat will need antihypertensive medication for life. It is also important to follow up on diagnosed cases. As well as re-checking the SBP after seven to 10 days and adjusting the medication dosage, remember that most of these cats will have underlying disease – most commonly CKD – and so monitoring and management of both conditions is needed.

These are often fragile cats, and attending to aspects such as nutrition and stress, analgesia for osteoarthritis as a comorbidity is important for quality of life, and longevity.

What do we know about prognosis?

Conroy et al (2018) examined survival after diagnosis of hypertension in 282 cats in the UK. Cats diagnosed as part of screening (due to pre-existing disease) had improved survival over those diagnosed due to clinical signs of hypertension (supporting the promotion of early diagnosis). Estimated median survival time of cats with seven or more days of follow up was 400 days (interquartile range 147-797). In this study, when the original larger group of cat consultations were analysed, a total of only 1 in 23 cats aged nine years or older had blood pressure assessed, showing room for improvement in identifying cases. The findings of this study support the experience that cats treated for hypertension can do well, with prolonged survival and good quality of life.

A team approach to diagnosis and treatment of hypertension

We cannot treat hypertension if we do not detect it, and barriers exist to bringing cats to the clinic – perhaps even more so with older cats. Signs can be subtle, and cats often will not be presented specifically for SBP assessment, rather for clinical signs of other disease (for example, weight loss with CKD).

Additionally, opportunities can be missed when cats are in the clinic for other reasons, such as the treated hyperthyroid cat attending for thyroxine measurement. Therefore, raising owner awareness of hypertension has value to increase understanding of why it is important to present cats for screening – particularly if they have associated conditions (for example, CKD and hyperthyroidism).

While ideally senior clinics are created, including measurement of bodyweight/condition, urinalysis and SBP measurement, this can take time and effort, so starting with a process of measuring SBP in cats with azotaemia, for example, and building from this, can make increasing SBP measurement feel more achievable in a busy clinic.

Veterinary nurses are vital in improving frequency of SBP measurement in clinics via specific nursing clinics, measurement of SBP during consulting periods and in hospitalised patients, as well as improving owner communication and awareness.

Pricing of SBP measurement can be a contentious issue and create its own barrier to diagnosis of hypertension, although research shows this may not be as much of a barrier to owners as we perceive or assume. In some clinics, SBP may be priced in different ways by different staff members and even have more than one code and cost.

A clinic meeting to see how this can be affordably incorporated into consultation fees, or blood/urine pricing bundles, may be productive.

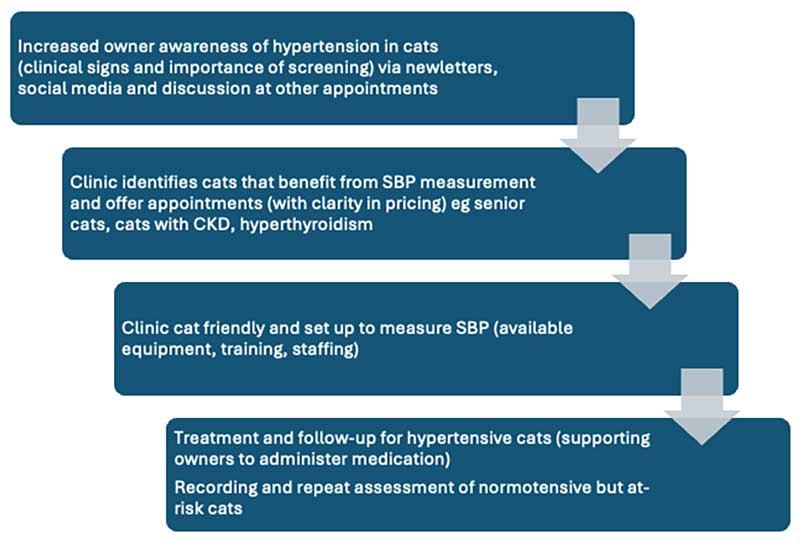

Importantly, value exists in recording normal readings in healthy older cats, to allow observation of increasing SBP trends in individual cats. Figure 3 shows different areas of focus in improving the detection of hypertension.

Audits can work for identifying hypertensive cats

In 2024, CVS ran a group-wide clinical project to increase early identification and treatment of hypertension, which was named QI winner in the RCVS 2024 Quality Improvement Awards.

The initiative nominated people in each clinic to promote measurement of blood pressure and become a point of contact for communicating with owners and staff.

Additional CPD and resources were provided. The initiative involved an audit of blood pressure measurement in clinics prior to the project, revealing only 1% of animals aged seven years and older had annual SBP screening. CPD sessions were held to identify barriers to SBP measurement, including confusion around pricing, confusion and confidence around equipment use, and lack of time and equipment. These barriers were tackled with the purchase of equipment, but also ensuring availability of equipment (for example, an all-in-one dedicated container), providing clarity around charging, and specific marketing and identification of at-risk cats, such as those with CKD and hyperthyroidism.

During the 2022-23 re-audit, a 110% increase in SBP screening was recorded at the focus sites with a 34% increase in prescription of anti-hypertensive medication, showing that increasing the frequency of SBP measurement results in identification and treatment of hypertensive cats.

Read more about this initiative online (bit.ly/42Uqng9) and consider how you could apply some of the ideas to your clinic.

Conclusion

A growing body of research is helping us understand more about hypertension in our feline patients, which is fantastic, but in parallel implementation of initiatives to normalise routine SBP assessment of senior cats must be the aim.

What are the barriers in your clinic? This may vary between hospitals, so a bespoke and manageable plan, starting with increasing SBP measurement in the most at-risk patients, could be the subject of your next clinic meeting.

- Use of some of the drugs in this article is under the veterinary medicine cascade.

- This appeared in Vet Times (2025), Volume 55, Issue 19, Pages 6-9.

References

- Cases C and Dye C (2024). Comparison of Thames Medical CAT+ Doppler and SunTech Vet 20 oscillometric devices for non-invasive blood pressure measurement in conscious cats, J Feline Med Surg 26(2): 1098612X231216350.

- Conroy M et al (2018). Survival after diagnosis of hypertension in cats attending primary care practice in the United Kingdom, J Vet Intern Med 32(6): 1,846-1,855.

- Costa Vitor R et al (2024). Body condition scores in cats and associations with systolic blood pressure, glucose homeostasis, and systemic inflammation, Vet Sci 11(4): 151.

- Flora Z et al (2025). Cardiac pathology associated with hypertension and chronic kidney disease in aged cats, J Comp Pathol 216: 40-49.

- Knies M et al (2024). Comparison of Doppler ultrasonic sphygmomanometry, oscillometry and high-definition oscillometry for non-invasive blood pressure measurement in conscious cats, J Feline Med Surg 26(3): 1098612X241231471.

- Meng L et al (2024). Effect of oral administration of pregabalin on physiological and echocardiographic variables in healthy cats, J Feline Med Surg 26(7): 1098612X241250245

- Stammeleer L et al (2024). Blood pressure in hyperthyroid cats before and after radioiodine treatment, J Vet Intern Med 38(3): 1,359-1,369.

- Veronezi TM et al (2022). Evaluation of the effects of gabapentin on the physiologic and echocardiographic variables of healthy cats: a prospective, randomized and blinded study, J Feline Med Surg 24(12): e498-e504.