24 Jun 2025

First opinion approach to chest x-ray interpretation

Rory Thomson BVMS, MRCVS considers the radiography differences in human and veterinary health during diagnosis.

Image: lenets_tan / Adobe Stock

In the first part of this series (VT55.06), a comparison was made regarding the medical work-up of a dog with a chronic cough to that of the author’s 10-year-old daughter.

A case report was presented of a one-year-old female Labrador retriever with a cough, which had an incredibly unusual work-up for a veterinary patient with the admission at the end of the report that it was not a Labrador, but the author’s daughter.

After four weeks of the child’s cough, she was referred for a chest radiograph. This article will elaborate on the author’s point of view regarding his experience with whooping cough, focusing in particular with some of the differences between the veterinary and human clinicians approach to chest radiography.

Experiencing whooping cough

Watching my 10-year-old daughter suffer for months with Bordetella pertussis (whooping cough) has been the single worst thing I have had to endure. She would have paroxysms of coughing continuously until no air was left in her lungs.

There would then be a pause that seemed to last forever as she turned cyanotic, before a vital gasp of air enabled her mucous membranes to return to a normal pink colour. Often during these attacks, she would vomit.

These paroxysms would come from nowhere while my daughter was carrying out her normal daily tasks and she could be absolutely fine between these paroxysms, so when we took her to the GP there was never a concern, as all her vital signs were normal.

During the recovery, the paroxysms reduced in frequency and severity, but my wife and I still faced months of a dry, irritating cough that would recur every few seconds, preventing my daughter from getting the sleep required to recover. My wife resorted to sitting with her on the bathroom floor, reading to her for hours at a time with the shower on the hottest setting and the windows and doors closed to steam her. Once the shower ran out of hot water, we used a kettle. This was the only way of settling the cough.

There were a few nights we placed a mattress on to the bathroom floor to enable her to sleep. Desperation led us to seek a private respiratory paediatrician to achieve a diagnosis and some palliative treatment in the form of nebulised budesonide and antihistamines to help her sleep at night, but ultimately we had to wait for this “100-day cough” to run its course.

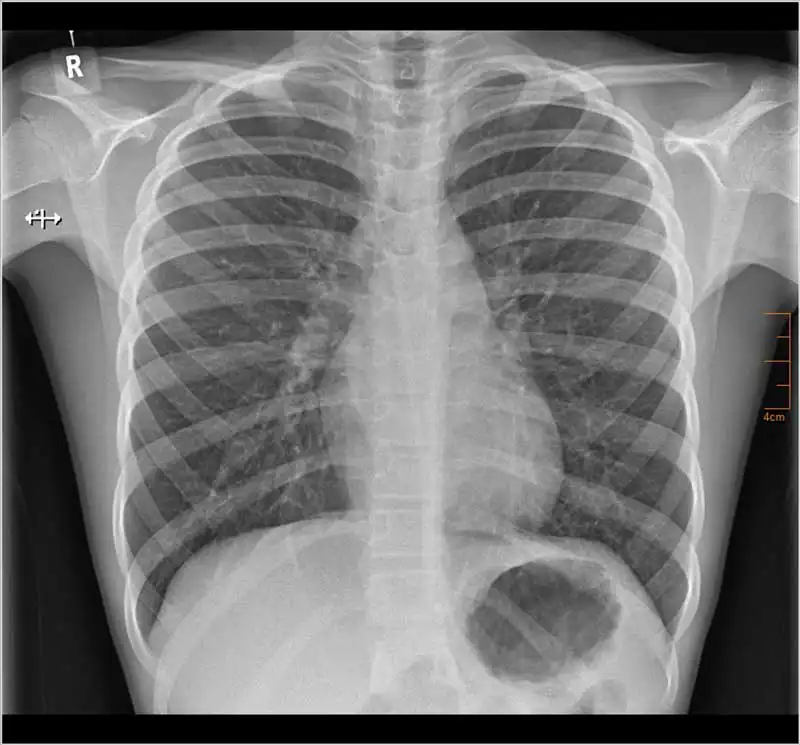

Before achieving the diagnosis privately, some imaging of my daughter’s chest was obtained through a GP referral, which at the time was to attempt to achieve a diagnosis of what had become a persistent cough. Figure 1 shows the entire x-ray study completed for my daughter.

Thoracic radiography comparisons

As practitioners in veterinary medicine, we know that although chest radiographs can provide a definitive diagnosis in some disease processes, chest radiographs are now often better utilised as a screening test to help support or exclude a working differential diagnosis, rather than providing the definitive diagnosis.

It is important to communicate this to clients, as they may expect the cause of their pet’s cough to be diagnosable on a chest x-ray alone, and a chest x-ray within normal limits does not necessarily exclude significant pathological changes within the thorax.

Any abnormalities detected may require further imaging to provide that definitive diagnosis. However, the images obtained may provide enough information to support a diagnosis and start treatment, but the limitations of the radiographic findings must be understood, and that diagnosis questioned if the patient fails to respond as anticipated to the treatment provided.

One of the golden rules of plain radiographs in veterinary medicine is to always take more than one view. With chest radiographs, this is a minimum of a lateral and a dorsoventral view. In veterinary patients, it has been shown that a third view (including left lateral, right lateral and dorsoventral views) will alter the diagnosis in 12 per cent to 15 per cent of patients evaluated for structured interstitial pulmonary disease1.

In veterinary patients, there is a great variation in normal anatomy between different breeds. Dogs with an egg-shaped chest, such as the German shepherd dog, have a different anatomy to the barrel-shaped chest of a bulldog, and so differentiating normal anatomical variations from pathology is much more difficult for our veterinary patients, meaning that it is more common to require more views to achieve the correct diagnosis.

Most mammalian species have a laterally compressed thorax compared to the dorsoventrally compressed thorax of a human. While the right lateral view provides the most information for canine patients, the ventrodorsal view is most valuable to our human medical colleagues.

The radiographic study for my daughter consists of a single frontal (ventrodorsal) view of the thorax. While three views are considered optimal for veterinary patients, a single frontal view is standard practice in medicine, with other views taken if deemed necessary. Data is limited to support the benefits of additional views in human medicine, with evidence that a second view will only alter the diagnosis in two per cent to three per cent of paediatric cases2, and so the benefits of taking multiple views weighed up against the risk of patient radiation exposure and cost may not justify the additional views.

In veterinary practice, the veterinary surgeon will usually assess the images in light of the clinical history and physical exam findings. If a radiography report is requested, the veterinary surgeon may go back to the person writing the report and seek further clarification over any areas they may be concerned about, based on their history and physical exam findings; occasionally, subtle lesions may subsequently be identified that are deemed significant based on that additional information.

I was surprised when both the GP and the respiratory consultants responsible for my daughter were unable to see the chest x-ray, and only had access to the radiography report provided by a radiography consultant. As such, I was expecting a fairly detailed report for this image. The clinical history was brief and stated: “Persistent cough? Cause? Why cough?”. I was incredibly surprised to find that the radiographic findings consisted of a single line stating: “The heart and mediastinal contours are within normal limits, the lungs are clear.”

The radiographic diagnosis was simply: “Normal.” There was no further description or interpretation provided. I strongly dislike the word “normal” in clinical notes. Very rarely can we state with certainty that something is normal and this can lead us into trouble with clients when, retrospectively, abnormalities are identified. If a CT scan is performed and identifies an irregularity, you can often review the x-ray and retrospectively identify a subtle change that was there all along.

In my opinion, the term “NAD”, meaning “no abnormalities detected”, or “WNL”, meaning “within normal limits”, is much more appropriate. These three little letters very quickly identify that an area has been assessed and no abnormalities have been detected, but very honestly does not say that they are normal. If you have a chronic cough, something in the chest is likely to be abnormal and if you know where to look, you may find it.

Looking at my daughter’s x-ray through the eyes of a first opinion vet, there appears to be a significant “bronchial pattern” present that had not been mentioned within the radiographic report. A bronchial pattern would be expected with a chronic cough in our veterinary patients, as there is likely to be inflammation present causing that cough. This may be visible radiographically, although the cause of that inflammation may not be possible to identify on a radiograph.

The benefits of lung pattern reporting has been questioned in human radiography since the 1970s, where the patterns identified could not be accurately matched to the clinical diagnosis or the histopathological location of the disease3. As a result, it appears that human radiographers have moved away from the documentation of these patterns. In the 1990s, the benefits of reporting pulmonary patterns in veterinary patients was also criticised4. More recently, in 2002, it was suggested to move away from documenting the “radiographic pattern” and, more specifically, document the “radiographic signs”5.

These radiographic signs are easier to recognise and document consistently between practitioners based on the opacity, location, size and severity. Unfortunately, this often results in the phrase, “increased soft tissue opacity”, which covers most of the traditional lung patterns and is very non-specific. It is, therefore, advisable only to document this radiographic sign if it is thought to be related to clinical disease, as other factors can cause this radiographic sign such as obesity, under-inflation and radiographic technique. It is, therefore, essential to understand the history and physical examination findings of the patient to determine whether this radiographic sign should be reported.

The lines and rings seen in my daughter’s radiographs (which I would class as typical of a bronchial pattern if seen on a veterinary x-ray) are not specific to bronchial disease. This means a radiographic diagnosis can not be made.

It is common in veterinary radiography to identify a bronchial pattern on chest radiographs. The significance of this bronchial pattern is difficult to conclude radiographically, as it may be completely benign and relating to under-inflation or age-related changes within the pulmonary parenchyma.

In a patient with respiratory signs, I still think it is worth documenting, as the cause of the bronchial pattern may be contributing to the clinical signs and may help support a working differential diagnosis.

When I asked the health care professionals examining my daughter about whether they wanted to see the radiograph, it was surprising to hear that they felt it was unnecessary, as the person interpreting the image was far more qualified to do so than they were. With the emergence of various veterinary telemedicine companies able to provide veterinary surgeons with comprehensive reports from imaging specialists, this may be the attitude veterinary general practitioners of the future will follow.

As the radiographic interpretation is provided in light of physical exam findings, it is essential that excellent ongoing communication exists in both directions between all clinicians involved with a case, to ensure optimal patient care.

With the advancements made to veterinary diagnostics, x-rays are becoming less and less relied on for achieving a diagnosis. The availability of other, more sensitive imaging modalities, including better quality and more readily available echocardiography, thoracic ultrasound and CT scans, means that general practitioners may not be as reliant on identifying more subtle changes on chest radiographs as they used to be.

A final digression

A massive frustration for me and my wife was watching our entire village suffer with this same disease (although, most of them did seem to experience much milder clinical signs).

Parents were suffering with coughs they just couldn’t shift, and classmates and siblings were coughing continuously to the point that teachers were unable to be heard in the classroom. At this point, whooping cough was confirmed in our daughter by an oral swab and we were fairly certain that everyone else in the class and village had this same disease.

Whooping cough is legally reportable and often fatal to unvaccinated babies younger than six months. In January 2024, once we had a diagnosis, we attempted to highlight the disease through the school and local media; however, rather than investigating this outbreak, the UK Health Security Agency (UKHSA) adamantly denied there being any evidence of an outbreak. Others were sometimes told they had whooping cough, but it was not reported. As the numbers of reported cases were still below pre-COVID levels, the school was advised against notifying parents of the outbreak and the control measures available to limit the spread of the disease.

It was not until six months after my daughter started with clinical signs, in May 2024, that UKHSA acknowledged a rise in cases of Bordetella pertussis after five infant deaths between January and March 20246.

I know a lot of Vet Times readers like a good book review, and for anyone who has experienced whooping cough or has been touched by my experience with my daughter, I recommend reading Outbreak in the Village by Douglas Jenkinson7 (Figure 2). It is an inspiring book, sharing the life work of a medical GP who followed outbreaks of whooping cough in his village over decades and identified problems with the education of GPs when it came to the diagnosis of whooping cough.

He developed tests to confirm whooping cough in his patients and highlighted the issues regarding reporting of this disease, which are just as problematic now as they were decades ago. This is unbelievable given the recent global pandemic where infectious diseases and their spread should still be at the forefront of our minds.

What I find incredibly frustrating is that the UKHSA has still failed to identify this as an outbreak despite the significant increase in cases and the first infant deaths since 2019. UKHSA has publicly emphasised the need for higher vaccination rates in pregnant women; however, it has not acknowledged that there is a massive problem with the prompt diagnosis and reporting of this disease, which could enable additional control measures to be put in place to limit the spread of an outbreak.

The book, Outbreak in the Village, also shows that you don’t have to be a specialist in a particular field to be able to conduct research, and I believe that general practitioners like myself in veterinary practice should not be deterred from gathering data and outcomes from their cases and publishing them for colleagues.

General practitioners are just as well placed as specialists to help develop the evidence base we are using. We are always striving to improve our approach and treatment of cases. There may be some good techniques individuals have developed themselves in first opinion practice that are effective.

The common, everyday cases dealt with predominantly in first opinion practice may have a smaller evidence base, as the evidence has simply not been documented. Some of these techniques are getting dismissed in our ever-increasing “evidence-based medicine” culture because there has been no published evidence that they work, but on the flip side, there may also be no evidence that they don’t work, either.

- This article appeared in Vet Times (2025), Volume 55, Issue 25, Pages 12-17

- Part one is available here.

References

- 1. Ober CP and Barber D (2006). Comparison of two- vs. three-view thoracic radiographic studies on conspicuity of structured interstitial patterns in dogs, Vet Radiol Ultrasound 47(6): 542-545.

- 2. Lynch T, Goujn S, Larson C and Patenaude Y (2003). Should the lateral chest radiograph be routine in the diagnosis of pneumonia in children? A review of the literature, Paediatr Child Health 8(9): 566-568.

- 3. Felson B (1979). A new look at pattern recognition of diffuse pulmonary disease, AJR Am J Roentgenol 133(2): 183-189.

- 4. Farrow CS (1995). Critical thinking: the perils of pattern recognition, Can Vet J 36(1): 57-58.

- 5. Nykamp SG, Scrivani PV and Dykes N (2002). Radiographic signs of pulmonary disease: an alternative approach, Compend Contin Educ Pract Vet 24(1): 25-36.

- 6. BBC News (2025). Whooping cough: Cases up again as five infant deaths reported, tinyurl.com/35wa5uv8

- 7. Jenkinson D (2020). Outbreak in the Village: A Family Doctor’s Lifetime Study of Whooping Cough, Springer Biographies, Cham.